Introduction

Much ink has been spilt over attempts to define social movements. Dieter Rucht (born 1946) has argued that they are "a network of individuals, groups and organizations that, based on a sense of collective identity, seek to bring about social change (or resist social change) primarily by means of collective public protest."1 It is a very broad and inclusive definition that takes into account that social movements often have, as Sidney Tarrow (born 1938) put it, 'fuzzy' borders and are 'moving targets' where it might not be sensible to define them more precisely.2 What seems to characterize social movements is the networked character of their organization. Friedhelm Neidhardt (born 1934) has talked about a social movement as a 'mobilized network of networks' with an absence of a clear top and a clear centre.3 They are held together, above all, by the construction of identities by its members, who, through a variety of cultural processes, create a 'we'-feeling by identifying with particular issues, concerns and desires. These can be essentialist and exclusive, or they can be self-reflective, playful and situational. Stuart Hall's (1932–2014) concept of 'identification' was meant to provide a conceptual base from which emancipatory social movements can organize without falling into the trap of essentialism.4

Since the 1970s a new discipline has formed – social movement studies that is dedicated to the study of social movements. Like any new discipline it has established its own research centres. In Germany the Institute for Social Movements at Ruhr-Universität Bochum is one of the foremost centres for the study of social movements, although it is unusual because it is more historically oriented than social movement studies as a whole, where most researchers come from the social sciences.5 The Institute for Protest and Movement Research is another important institution in Germany dedicated to the study of social movements, which is more oriented towards the social sciences.6 Many countries all over the world have similar research centres apart from individual researchers who work both within and outside of universities. Activists within social movements are often doing research about social movements. There are a number of established journals, such as Social Movement Studies, Mobilization, Interface: a Journal for and about Social Movements and Moving the Social: Journal for Social History and the History of Social Movements. Whilst the first three are oriented towards the social sciences, the latter is the only international journal in the English language dedicated specifically to the history of social movements.7 In other languages we also find additional journals, e.g. in German the Forschungssjournal Soziale Bewegungen, and in French Le Mouvement Social.8 Many handbooks and surveys have been published to give an overview of the discipline and its achievements.9 Several publishers have established book series on social movement studies, including series on the history of social movements.10

Surveying the discipline, it is clear that social scientists, sociologists, political scientists, geographers, and anthropologists have been dominating the field. Hence it is not surprising that much research is about contemporary social movements. In so far as social movement studies have adopted a historical approach it is very much a contemporary history approach. Very rarely have studies moved before the annus mirabilis of social movement studies: 1968. It was in the wake of the 1968 movement that a range of so-called 'new social movements' started which subsequently became the preferred study object of social movement researchers who often had considerable political sympathies for these movements. However, it should be noted that some of the older work of distinguished historical sociologists, like Charles Tilly (1929–2008) and Sidney Tarrow, did adopt an approach that trace social movements back at least to the 18th century.11 There are also some studies of social movements in premodern societies, i.e. peasant revolts

that a range of so-called 'new social movements' started which subsequently became the preferred study object of social movement researchers who often had considerable political sympathies for these movements. However, it should be noted that some of the older work of distinguished historical sociologists, like Charles Tilly (1929–2008) and Sidney Tarrow, did adopt an approach that trace social movements back at least to the 18th century.11 There are also some studies of social movements in premodern societies, i.e. peasant revolts , guild movements, food riots

, guild movements, food riots , millenarian movements, journeymen's movements and rebellions for greater social and political rights that preceded capitalist industrial society

, millenarian movements, journeymen's movements and rebellions for greater social and political rights that preceded capitalist industrial society .12 As Marcel van der Linden (born 1952) has argued, the search for social justice, social security and respect through social movements preceded modern times.13 However, most researchers have understood social movements as a distinctly modern phenomenon arguing that the idea that social change can be brought about through the will of human beings is a distinctly modern idea rooted in Enlightenment notions of the 18th century. Social movements in premodern times were far more likely to argue in terms of 'natural rights' or a godly social order that had to be re-established.14 This tradition, though, did reach deep into modern times, as Edward P. Thompson's (1924–1993) study on the 'moral economy' of the 18th century crowd showed.15 The popularity of that concept of 'moral economy' for the study of modern social movements seems to underline the need to re-examine the tight line between premodern and modern social movements.16 A deeper look into the past of social movements that range back in time certainly well before 1968 and even before the second half of the 18th century might well make that border far more fluid.

.12 As Marcel van der Linden (born 1952) has argued, the search for social justice, social security and respect through social movements preceded modern times.13 However, most researchers have understood social movements as a distinctly modern phenomenon arguing that the idea that social change can be brought about through the will of human beings is a distinctly modern idea rooted in Enlightenment notions of the 18th century. Social movements in premodern times were far more likely to argue in terms of 'natural rights' or a godly social order that had to be re-established.14 This tradition, though, did reach deep into modern times, as Edward P. Thompson's (1924–1993) study on the 'moral economy' of the 18th century crowd showed.15 The popularity of that concept of 'moral economy' for the study of modern social movements seems to underline the need to re-examine the tight line between premodern and modern social movements.16 A deeper look into the past of social movements that range back in time certainly well before 1968 and even before the second half of the 18th century might well make that border far more fluid.

What is certainly misleading is to talk about 'new' social movements as if many of these movements only originated in a post-1968 cycle of contention. The most-discussed 'new' social movements, including the peace, women's and environmental movements all go back many centuries and have strong precursors already in the 19th century. At the same time, allegedly 'old' social movements, such as labour movements, still exist in the 21st century and the concern with questions of social justice is in many respects as alive as it was in the 19th century. It is also not the case that 'old' social movements were more about material interests whereas 'new' social movements are more about questions of identity, as notions of collective identity were very much to the fore in social movements ranging back many centuries, whereas material interests play a significant role in many of the social movements in the post-1968 era.17

In the rest of this brief introduction to the history of international social movements before 1945 I will, after giving some thought to theories and problems of the study of those movements, provide the reader with a survey of social movements that have been studied indicating the major results of the research and highlighting avenues of research that would be well worth exploring further.

How to Study the Deeper History of International Social Movements

If social movement studies is in need of developing a deeper historical interest in the history of social movements, then it is also in need of learning to see on its right eye. An overwhelming number of studies on social movements have focused on broadly left-of-centre social movements. As mentioned above, this has much to do with the left-wing sympathies of social movement studies scholars. It is often more attractive to study something that one is in sympathy with than something that one finds repulsive. Nevertheless, many social movements have been on the political right which is why this survey will also include a section on nationalist and fascist social movements. Furthermore, the deeper history of social movements, often associated with the left, has a far more ambiguous past that is in need of greater exploration. The environmental movement, for example, is often identified with the political left, but especially if we go back in time to the 19th century, it becomes clear that it could also be a reactionary movement. Indeed, in some cases the categories of left and right can become questionable when studying the histories of social movements as it is not always obvious where to locate social movements on a left-right scale.18

Social movements have also long been studied in their national contexts, because scholarship was for a long time concerned with the nation state and national framings. A turn to study social movements transnationally and comparatively was re-enforced by the strong emergence of global history from the 1990s onwards.19 Studying advocacy networks in international politics brought attention to the diverse ways in which social movements are connected across national borders.20 A more global approach to the study of the history of social movements before 1945 would allow for the greater visibility of the connectedness of social movements and their genuine internationalism not only in the contemporary world but also in the past. At the same time, it will make it possible to pinpoint more precisely how the agency and structure of social movements was territorially specific and rooted in particular times and places. Both the opportunities and the limits of internationalism are thus revealed by more global approaches to the history of social movements.21

To what extent the concept of 'social movement' itself was a 'travelling concept' that can be applied to different parts of the world in equal measure has been controversially discussed.22 Other concepts crucial to the history of social movements, e.g. 'freedom', 'equality', 'peace', and 'emancipation' are all rooted in Western-centric traditions that need to be thoroughly de-westernised in transnational and global histories of social movements. Studying social movements transnationally and going beyond the global west or north will therefore destabilise the fixed meanings of key concepts in social movement studies and reveal to what extent such conceptualizations were themselves part and parcel of a long and ongoing history of colonialism and imperialism.23 A conceptual history of transnational social movements will pay close attention to the way in which the concept travelled both within Europe and North America and between the global north and south.24 Such travels always included various forms of translations that led to linguistic and cultural adaptations and modifications.25

There are undoubtedly international moments of protest that we can only identify in transnational perspective. Before 1945 it was particularly the period between the first Russian revolution of 1905 and the Asturian revolution of 1934 that saw a plethora of revolutions occur in different parts of the world. They often combined ideas of political democracy with notions of social justice and national liberation and were based on the mobilization of social movements fighting for those ideals.26 There are also waves of mobilization if we consider particular social movements. Thus, for example, anti-aristocratic social movements were prominent in the late 18th and early 19th centuries,27 anti-colonial and anti-imperial movements were strong from the early 20th century to the wave of decolonization after the end of the Second World War.28 Social protests against war were strong when a threat of war hung in the air, such as in the decade preceding the First World War.29 Waves of labour protest resulted in strike waves that have been studied by scholars of labour history.30 The struggle for women's rights saw several waves of mobilization with a first strong one emerging between the 1830s and the 1860s.31 The concept of generation has sometimes been used to account for particular waves of protest that seem to be connected to generational experiences.32

that saw a plethora of revolutions occur in different parts of the world. They often combined ideas of political democracy with notions of social justice and national liberation and were based on the mobilization of social movements fighting for those ideals.26 There are also waves of mobilization if we consider particular social movements. Thus, for example, anti-aristocratic social movements were prominent in the late 18th and early 19th centuries,27 anti-colonial and anti-imperial movements were strong from the early 20th century to the wave of decolonization after the end of the Second World War.28 Social protests against war were strong when a threat of war hung in the air, such as in the decade preceding the First World War.29 Waves of labour protest resulted in strike waves that have been studied by scholars of labour history.30 The struggle for women's rights saw several waves of mobilization with a first strong one emerging between the 1830s and the 1860s.31 The concept of generation has sometimes been used to account for particular waves of protest that seem to be connected to generational experiences.32

Decentering a western view on all these international social movements has been a major concern over the last decades. Postcolonial theory has been hugely influential here. It has drawn attention to social movements of the subaltern classes in the global south, as many postcolonial scholars have shown a deep interest in popular social movements, e.g. on the Indian sub-continent and in Latin America, including peasant movements.33 Giving the subaltern classes their rightful place in history has been a strong motivation for studying their social movements.34 Indigenous movements in Latin America were often movements of small peasants and landless labourers who had been expropriated by large European landowners and who struggled for greater political, social and economic rights from the 19th century to the present day.35

In order to understand social movements better, scholars have deployed a whole range of middle-range theories that we find throughout much of the scholarship on social movements.36 We already noted above the tendency to connect social movements to modernity and to processes of modernization – something that might well be in need of greater questioning. Social movements have also often been connected to the growth of the public sphere under conditions of modernity and have thus been connected to processes of democratization of society.37 Alternatively, social movements have been analysed as a threat and a menace to the stability of societies, where they command over crowd politics that could work both in democratic and anti-democratic ways.38

under conditions of modernity and have thus been connected to processes of democratization of society.37 Alternatively, social movements have been analysed as a threat and a menace to the stability of societies, where they command over crowd politics that could work both in democratic and anti-democratic ways.38

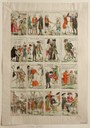

Furthermore, many studies have traced the 'repertoires of action' that characterized social movements across a very wide range of movements. In the 19th century, to give just one example, 'stumping'39 became a very popular transnational form of campaigning that mobilized democratic social movements in the US, Australia and Britain.40 Social movement scholars have also asked about the 'political opportunity structures' that have facilitated the emergence and guaranteed the success of social movements in the past. Resource mobilization theory has asked how organizers who mobilize social movements use resources. The 'framing' approach to the study of social movements has sought to show how specific political frames benefitted or held back social movements. What incentives were there for participation in social movements? What conditions would escalate conflicts? Many of these ideas were based on a cost–benefit analysis in which rationalist concerns weighed heavily either in favor or against the success of social movements.41 More recently irrational factors have also been stressed, including the power of emotions and of symbolical forms of politics. Social movements were embedded in wider cultures of protest whose cultural frames can only be understood by deploying cultural theories.42 The success of international social movements depended not only on the strengths of their rational arguments, but also on their ability to connect to the emotions of wider parts of the population. Hence scholars have attempted to bring together the history of emotions and the history of social movements.43

As many social movements put forward visions of imagined futures, social movement studies should take on board many of the insights of those historians who have studied how the future was imagined in the past. Reinhart Koselleck's (1923–2006) concept of 'futures past' and Lucian Hölscher's (born 1948) insistence on the importance of different temporalities of the diverse future imaginaries are useful for the study of social movements.44 Hölscher himself has studied this for Protestant and socialist movements.45 Others have picked up Hölscher's conceptualization of a history of the future and applied it to a range of other social movements both from the right and the left.46

If social movements can be usefully studied in view of their radical imaginations of futures, they can also be analysed in terms of what memories they generated and how they used memory as a political resource in order to further their specific aims.47 There have been a number of studies over recent years, in which a merger of memory studies and social movement studies has been attempted.48 Memories have been shown to be extremely useful for asserting claims, legitimizing politics and mobilizing support. Social movements have also been analysed as shapers of collective memories. Memory activism has been a prominent aspect of social movements.49 And many memory activists have used the media for transmitting memories to a wider public. Many international social movements have depended on the media for their campaigns, from newspapers in the 19th century to the internet in the 21st century, which is why the study of social movements needs to take into account the changing worlds of the media. Here media history meets a historically-oriented social movement studies.50

to the internet in the 21st century, which is why the study of social movements needs to take into account the changing worlds of the media. Here media history meets a historically-oriented social movement studies.50

Modern International Social Movements before 1945 – a Survey

Whilst social movements can be usefully studied in premodern times, some important changes occurred in the global north in the century between 1750 and 1850 that can be summarized in the processes of industrialization and democratization. Fundamental technological and economic changes went hand in hand with radical social and political changes that ultimately made a relatively static society, ordered into estates, give way to a more dynamic class-based society. Radical political movements reacting to those changes can be traced back to the early 19th century.51

The Labour Movement

In many respects the labour movements of the 19th century were the heirs of such radicalism, combining campaigns for democratization with campaigns aimed at solving the 'social question' produced by industrialization. Labour movements first emerged in the industrial centres of the global north. From there they travelled to all parts of the world and were adapted in a process of cultural translation in the global south that ultimately reached back to the centres of the global north.52 If labour movements in the global north in the 19th century saw themselves as advocates of industrial wage labour, a better understanding of the full diversity of labour regimes under capitalism, including many prevalent in the global south, have also widened the understanding of labour movements' advocacy on behalf of a range of different labourers. Socialist internationalism was strong among labour movements and led to the formation of various internationals before 1945, even if they were marked by a distinct Western-centrism.53 Labour movements developed three distinct pillars of organization: trade unions, cooperatives and political parties. They were divided by different ideologies: Socialism, Communism, Anarcho-Syndicalism, Christianity and Social Liberalism were among the most influential.54

of the global north. From there they travelled to all parts of the world and were adapted in a process of cultural translation in the global south that ultimately reached back to the centres of the global north.52 If labour movements in the global north in the 19th century saw themselves as advocates of industrial wage labour, a better understanding of the full diversity of labour regimes under capitalism, including many prevalent in the global south, have also widened the understanding of labour movements' advocacy on behalf of a range of different labourers. Socialist internationalism was strong among labour movements and led to the formation of various internationals before 1945, even if they were marked by a distinct Western-centrism.53 Labour movements developed three distinct pillars of organization: trade unions, cooperatives and political parties. They were divided by different ideologies: Socialism, Communism, Anarcho-Syndicalism, Christianity and Social Liberalism were among the most influential.54

Moral and Religious Reform Movements

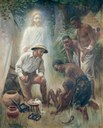

The labour movement was not the only international social movement fighting for greater social justice before 1945. Social reform movements, such as the one led by Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948)[ ] and Bhim Rao Ambedkar (1891–1956) in India could ally with labour movements but went beyond them.55 Gandhism produced its own world-wide social movement based on Gandhi's ideas and actions, in particular around non-violent resistance to colonial oppression, truth, simple living and vegetarianism.56 Highly critical of the first wave of globalizationin the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of these reform movements championed a variety of protest techniques in order to critique capitalism's ongoing production of social injustice and they sought to champion alternative socio-economic models more in line with their key demands of global social justice.57

] and Bhim Rao Ambedkar (1891–1956) in India could ally with labour movements but went beyond them.55 Gandhism produced its own world-wide social movement based on Gandhi's ideas and actions, in particular around non-violent resistance to colonial oppression, truth, simple living and vegetarianism.56 Highly critical of the first wave of globalizationin the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of these reform movements championed a variety of protest techniques in order to critique capitalism's ongoing production of social injustice and they sought to champion alternative socio-economic models more in line with their key demands of global social justice.57

Religion played a major role in many social reform movements. Thus, for example, the Catholic labour movement in Europe fought on behalf of workers and the religious reform movement of Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772–1833) in India also sought to bring about greater social justice.58 Religion also influenced a range of other social movements at various times – one only needs to think about the peace movement, the abolitionist movement or the temperance movement. Campaigns against the prohibition of alcoholic beverages led to bans of the sale of alcohol in Canada, the United States and Norway for specific periods of time between 1918 and the 1930s. Temperance movements promoted teetotalism as a virtue that had beneficial effects on medical, economic and moral well-being of individuals and societies as a whole. From the 1820s the movement grew in response to rising social problems associated not just with economic hardship but also with drink . From the 1860s it became an international mass movement with strongholds in Scandinavia, Britain and the US. Everywhere women activists were prominent in the movement

. From the 1860s it became an international mass movement with strongholds in Scandinavia, Britain and the US. Everywhere women activists were prominent in the movement .59 On the Indian sub-continent the temperance movement became closely allied to anti-colonialism.60

.59 On the Indian sub-continent the temperance movement became closely allied to anti-colonialism.60

Apart from the temperance movement, religion was a major influence on a range of moral movements that were working on behalf of what they understood to be moral improvement. In the 18th and 19th centuries aristocratic and bourgeois classes were often the main social carriers of these philanthropic movements. In the 20th century human-rights movements can also be examined as moral movements.61 And, in many respects, the labour movement was also a moral movement in that its arguments for greater social justice were frequently clad in moral terms. A moral international social conscience was formed by the temperance, the anti-slavery and the red cross/red crescent movements of the 19th century.62 Various anti-vice movements focusing often on drugs, drink and debauchery developed a very clear moral compass.63

and the red cross/red crescent movements of the 19th century.62 Various anti-vice movements focusing often on drugs, drink and debauchery developed a very clear moral compass.63

Yet there were also genuinely religious social movements which tended to be transnational, as religious beliefs crossed national boundaries.64 Catholic social movements, for example, were united in a belief in Catholic social thought that spanned the globe.65 Catholics and Protestants alike sought to spread their belief through strong missionary movements that were global in their ambitions.66 Religious awakenings could take the form of social movements.67 In the 20th century liberation theology provided a collective identity for a range of revolutionary social movements in Latin America and elsewhere.68

Youth Movements

The need for a new moral compass was not only felt by religious movements but also by the youth movement that emerged in response to industrial modernity and urbanization in the 19th century.69 The disaffected bourgeois youth was looking for ways to live more in harmony with nature and less alienated lives in what appeared to them as urban Gomorrahs. A romanticized longing for authenticity and nature went hand in hand with ideas about life reform, liberated sexuality and reform education. An international youth culture emerged that soon politicised itself – with more völkisch right-wing variants demarcating themselves sharply from proletarian youth movements that were close to the labour movements and religious youth movements, close to the Catholic and Protestant churches. A range of centrist movements were less clear-cut in their political ambitions but united in a vague aspiration for freedom and the experience of nature through travelling, hiking, camping and singing .70 The International Youth Hostel Movement has its origins in the international youth movement. The latter developed particularly strongly in the German lands but it was also present in a range of other western countries and certainly had a European and western dimension. In the interwar period, youth activists such as Rolf Gardiner (1902–1971) in Britain tried to forge transnational links to youth organizations in other European countries, especially to Germany in order to foster international peace and understanding.71

.70 The International Youth Hostel Movement has its origins in the international youth movement. The latter developed particularly strongly in the German lands but it was also present in a range of other western countries and certainly had a European and western dimension. In the interwar period, youth activists such as Rolf Gardiner (1902–1971) in Britain tried to forge transnational links to youth organizations in other European countries, especially to Germany in order to foster international peace and understanding.71

Peace Movements

Youth movements had an ambivalent relationship to war. Some of them heroized war as cleansing the moral corruptness of bourgeois society, whilst others were active on behalf of diverse peace movements. War was morally abhorrent to many peace campaigners across time and place. Yet peace movements did not operate with the same concept of 'peace' throughout time and place.72 In 19th century Europe the concern with 'peace' was often promoted by a range of liberal-bourgeois pressure groups before such concern turned into a mass politics, in which social movements featured prominently. Although the search for peace was, like gender equality, a universal concern, the movements promoting it were often highly nationally inflected.73 Not all activists in peace movements were necessarily pacifists, as the commitment to peace in specific circumstances did not necessitate a general rejection of violence under other circumstances. Peace movements tended to emerge as a reaction to war or in anticipation of a threat of war. They often promoted forms of peace education. Particular religious groups, such as the Quakers were prominent in many peace movements, and there was also considerable overlap between the women's movement and the peace movement. In Europe, the period from the 1860s to the 1880s with its prominent wars fought for the purpose of nation-building saw the emergence of peace leagues that often combined a commitment to democratic nation states with the building of 'eternal peace', in the famous phrase of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804).74 International law and forms of international arbitration

were prominent in many peace movements, and there was also considerable overlap between the women's movement and the peace movement. In Europe, the period from the 1860s to the 1880s with its prominent wars fought for the purpose of nation-building saw the emergence of peace leagues that often combined a commitment to democratic nation states with the building of 'eternal peace', in the famous phrase of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804).74 International law and forms of international arbitration were the means with which to bring about a state of peace. After the First World War the commitment to international organizations capable of protecting the peace, such as the League of Nations, was high among peace activists.75 New transnational organizations such as the War Resisters' International

were the means with which to bring about a state of peace. After the First World War the commitment to international organizations capable of protecting the peace, such as the League of Nations, was high among peace activists.75 New transnational organizations such as the War Resisters' International were founded, but the hope that the First World War had been 'the war to end all wars' were dashed in 1939.76

were founded, but the hope that the First World War had been 'the war to end all wars' were dashed in 1939.76

Nationalist and Right-Wing Movements

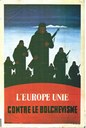

Peace campaigners in the 19th century had put considerable expectations in the coming of the democratic nation state. However, national movements and their ideology, nationalism, have been one of the most dangerous drivers of war and violence since the 19th century. Through the promotion of the idea that their nation was superior to other nations, nationalists heightened tensions between nations and would ultimately seek violent means, including wars, in order to push their claims for superiority over other nations. Both the First and Second World Wars as well as the colonial wars were rooted in the nationalists' belief in the cultural or biological superiority of nations. Nationalist movements, next to labour movements, belonged to the most successful 19th century social movements in mobilizing masses and providing them with a political religion, nationalism. They were rarely content with promoting a cultural nation but instead sought to create a sovereign nation state. The congruity of people, nation, and state was one of the most cherished principles of nationalist social movements.77

and providing them with a political religion, nationalism. They were rarely content with promoting a cultural nation but instead sought to create a sovereign nation state. The congruity of people, nation, and state was one of the most cherished principles of nationalist social movements.77

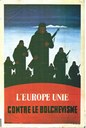

A 20th century form of hyper-nationalism was fascism. Fascist regimes were invariably preceded by and based on fascist social movements.78 The political violence at the end of the First World War was crucial in bringing them about in countries including Germany, Italy, Hungary and France. They often had their origins in paramilitary formations that fought left-wing revolutionaries after 1918. The success of fascism in Italy in 1923 encouraged other far-right movements to call themselves fascist even if most of them developed highly specific national inflections. The fascist movement in Germany, for example, was committed to a biological understanding of 'the people' (Volk) and the idea that it was threatened by 'Judeo-Bolshevism'. The Arrow Cross in Hungary and the Croix de Feu in France were other nationally inflected social movements, in which Catholic conservatism played significant roles. Everywhere fascist social movements practiced a pronounced masculinism showing a contempt for independent working women and an idealization of the woman as mother. By 1925 no fewer than 45 states had fascist movements.79 The movement character of fascism was dear to the fascists themselves, as it underpinned their notion of a dynamism uniting the nation around one ideology.80

in Hungary and the Croix de Feu in France were other nationally inflected social movements, in which Catholic conservatism played significant roles. Everywhere fascist social movements practiced a pronounced masculinism showing a contempt for independent working women and an idealization of the woman as mother. By 1925 no fewer than 45 states had fascist movements.79 The movement character of fascism was dear to the fascists themselves, as it underpinned their notion of a dynamism uniting the nation around one ideology.80

Far-right wing movements, often described as neo-fascist, continued to play a prominent role in different regimes and at different times from the post-Second World War period to the present day.81 They promoted various forms of racism, gender inequality and the idea of a national community threatened both by internal and external enemies. They showed considerable synergies with anti-immigrant and anti-abortion movements and with fundamentalist religious movements, such as the Christian Identity Movement in the US or the Hindutva movement in India. Extreme right-wing social movements in the post-1945 world have often reacted against social developments such as the emergence of multi-culturalism, increasing rights for the LGBTQ community or increasing religious diversity. They have thus framed their own struggle as one of the dispossessed who are threatened by social developments outside of their control. An essentialist identity is constructed that is then described as being under threat. Self-victimization thus becomes an integral element of nationalist mobilization among the far right. In many places it has been successfully mobilizing the street and public spaces. The recent surge of right-wing populism is the latest instalment of a long-standing story of right-wing social movements going back to the early 20th century.82

Pan-Movements

At different times and places pan-movements played an important role in underpinning social movements seeking to unite collectives under the banner of an ideology that transgressed nation-state boundaries.83 Thus, for example, pan-Germanism and pan-Slavism were 19th and 20th century ideologies that often hid the imperialist ambitions of Germany and Russia respectively, the former intent on building, the latter keen to defend and extend a contiguous empire.84 Pan-Scandinavianism sought to emphasize the cultural affinities between the Scandinavian countries in an attempt to overcome nation-state rivalries and enmities, amidst complex nation-state building processes in Iceland, Finland and Norway.85 Pan-Iberianism was a means of connecting culturally two nation states and their associated empires in Latin America and Africa, constructing a mutual space of civilizational understanding that could also be a form of neo-imperialism.86 Pan-Arabism, Pan-Africanism and Pan-Asianism were powerful weapons of an anti-colonial and anti-imperial discourse in the 20th century, although Pan-Asianism was also used as an anti-Western front by Japanese imperialism before 1945.87

National Liberation Movements

National liberation movements emerged in the context of the anti-colonial struggles starting in Latin America in the early 19th century and spreading to all parts of the colonized world by the 20th century.88 They also occurred in Europe where national movements struggled to free 'their' respective nations from the clutches of empires and multi-national states, e.g. in Ireland and on the Balkans.89 National liberation movements constructed new forms of community around allegedly distinct national cultures and they adopted a range of practices which cemented allegiances to those cultures.90 Post-independence many of the postcolonial states embarked on projects of developmentalism trying to catch up with the colonial metropoles. Third-worldist social movements sought to support the postcolonial countries, mostly located in the global south that were struggling to move out of cycles of poverty and underdevelopment.91 It was strongly international in orientation seeking to connect global interdependencies and structures of exploitation to a systematic and enduring disadvantage for countries located in the so-called 'Third World'.

and spreading to all parts of the colonized world by the 20th century.88 They also occurred in Europe where national movements struggled to free 'their' respective nations from the clutches of empires and multi-national states, e.g. in Ireland and on the Balkans.89 National liberation movements constructed new forms of community around allegedly distinct national cultures and they adopted a range of practices which cemented allegiances to those cultures.90 Post-independence many of the postcolonial states embarked on projects of developmentalism trying to catch up with the colonial metropoles. Third-worldist social movements sought to support the postcolonial countries, mostly located in the global south that were struggling to move out of cycles of poverty and underdevelopment.91 It was strongly international in orientation seeking to connect global interdependencies and structures of exploitation to a systematic and enduring disadvantage for countries located in the so-called 'Third World'.

Women's Movements

Like many social movements, 'Third Worldism' had its origins well before 1945. The same is true for the women's movement that was formed in the 19th century as an international movement for the liberation of women from patriarchal oppression. In the second half of the 19th century a proletarian women's movement split off from the bourgeois women's movement arguing that questions of gender equality had to be approached within a wider frame of class inequalities.92 The development of universal forms of feminism have often been highly Western-centric and have been criticized by those scholars infused with postcolonial theories.93 Nevertheless, the women's movement had a global universal aim: the liberation of women. A strict separation of spheres was at the bottom of gender orders that discriminated against women in many places. A public sphere for men was juxtaposed to a private sphere for women. A productive sphere for men was contrasted with a reproductive sphere for women . Yet the gender orders that emerged from these separation of spheres remained highly space- and time-specific.94 And they produced diverse currents of women's movements that took different organizational forms and developed distinct discursive practices and symbolical politics. They also forged different alliances. Regardless of the many forms that women's movements could take in different parts of the world, they often were characterized by strong attempts to build alliances across national and cultural borders.95 The International Council of Women

. Yet the gender orders that emerged from these separation of spheres remained highly space- and time-specific.94 And they produced diverse currents of women's movements that took different organizational forms and developed distinct discursive practices and symbolical politics. They also forged different alliances. Regardless of the many forms that women's movements could take in different parts of the world, they often were characterized by strong attempts to build alliances across national and cultural borders.95 The International Council of Women was already established in 1888. The International Women's Suffrage Alliance

was already established in 1888. The International Women's Suffrage Alliance organized around one of the central concerns of the 19th and early 20th century women's movement: the right to vote

organized around one of the central concerns of the 19th and early 20th century women's movement: the right to vote . The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, founded in 1915, combined a concern for women's rights with social justice and peace.96

. The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, founded in 1915, combined a concern for women's rights with social justice and peace.96

Parts of the transnational women's movement also fought for the sexual liberation of women. A loosely connected movement for free love emerged in the late 19th century and grew in strength during the first half of the 20th century.97 They campaigned against marriage as a form of oppression for women consistent with patriarchal gender norms. With strong links to socialism and anarchism, but also to bohemianism and spiritualism, the free love movement had a number of prominent and outspoken advocates in different parts of the world, including William Blake (1757–1827), Mary Wollstonecraft (1797–1851), Charles Fourier (1772–1837), Edward Carpenter (1844–1929) and Emma Goldman (1869–1940). Amongst those members of the free love movement we also find many who were in favour of decriminalizing laws directed against homosexuality. A nascent transnational LGBTQ movement began to form during the first half of the 20th century. Although it still lacked a firm organizational frame, networks of campaigners were in regular transnational contact in order to exchange ideas and promote policies aimed at decriminalizing deviant forms of sexuality. It held up the legal reform first introduced by the French Revolution in 1791 that made homosexual sexual acts performed by consenting adults in private legal. The French reforms had resulted in similar reforms in a range of other European countries in the early 19th century, but soon the trend was reversed almost everywhere. Fears of reprisals, imprisonment and persecution made open campaigning on behalf of the rights of homosexuals and others with a non-hetero sexual orientation extremely dangerous and difficult.98

Movements for Racial Equality

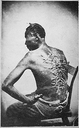

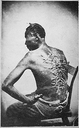

Women were also prominent among social movements for racial equality. They ranged from the abolitionist movement to the civil rights movement in the US and the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. Starting in the late 18th century, the anti-slavery movement questioned the moral legitimacy of enslaving fellow men . Whilst it became a mass movement especially in Britain and the United States, anti-slavery movements also emerged on the European continent and they were characterized by strong networks across national borders. The French Revolution first abolished slavery in 1794 followed by Haiti which established itself as an independent republic following a successful slave rebellion. It was the first country in the Americas to abolish slavery.99

. Whilst it became a mass movement especially in Britain and the United States, anti-slavery movements also emerged on the European continent and they were characterized by strong networks across national borders. The French Revolution first abolished slavery in 1794 followed by Haiti which established itself as an independent republic following a successful slave rebellion. It was the first country in the Americas to abolish slavery.99

In the US, slavery was ended following the American civil war of the 1860s, but massive discrimination against the black population and de-facto apartheid continued in all of the American states . A right-wing racist social movement, the Ku-Klux clan resorted to lynchings, bombings and other campaigns of murder in order to fight against the emancipation of black people.100 In response African-Americans and their allies began an ongoing struggle against racial discrimination. They formed a civil rights movement that fought against the so-called Jim Crow laws in the south of the US legitimating ongoing racial discrimination. They practiced diverse forms of civil disobedience, sit-ins and mass protests in order to make themselves heard in American society

. A right-wing racist social movement, the Ku-Klux clan resorted to lynchings, bombings and other campaigns of murder in order to fight against the emancipation of black people.100 In response African-Americans and their allies began an ongoing struggle against racial discrimination. They formed a civil rights movement that fought against the so-called Jim Crow laws in the south of the US legitimating ongoing racial discrimination. They practiced diverse forms of civil disobedience, sit-ins and mass protests in order to make themselves heard in American society . The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and several landmark rulings of the Supreme court in the 1950s and 1960s marked a breakthrough on the road to greater racial equality in the US after a century of struggle

. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and several landmark rulings of the Supreme court in the 1950s and 1960s marked a breakthrough on the road to greater racial equality in the US after a century of struggle , but even today movements such as the Black Lives Matter movement underline to what extent African Americans remain second-class citizens in their own country.101

, but even today movements such as the Black Lives Matter movement underline to what extent African Americans remain second-class citizens in their own country.101

Post-1945 one of the worst apartheid regimes was created in South Africa. International resistance against it was mobilized by an anti-apartheid movement that was strongest in Britain but had supporters all over the world. It started off as a consumer boycott movement calling on the public not to buy South African goods. It campaigned in favour of economic and other sanctions, including a ban of sporting links with South Africa. Under pressure from the international anti-apartheid movement South Africa was forced out of the Commonwealth in 1961. In 1970 it was banned from participating in the Olympics. There was also a campaign to end all academic cooperations with South African universities. Over many decades it kept the momentum going of a "Free Nelson Mandela" campaign organizing freedom marches and rock concerts .102 Overall, racism has created a range of social movements both promoting racism and opposing it that go back a long time in history – all the way to the anti-slavery campaigns of the 18th century.

.102 Overall, racism has created a range of social movements both promoting racism and opposing it that go back a long time in history – all the way to the anti-slavery campaigns of the 18th century.

The rights of first nations made up of indigenous people from Canada and the US to Australia and other parts of the colonized world, who all suffered massive racism and racial discrimination, also triggered powerful social movements.103 Fighting exclusion and dispossession, these movements strove for self-determination and the preservation of indigenous culture and heritage ever since colonization started in the 16th century. They campaigned for better health provisions[ ] and access to resources to get indigenous people out of a vicious circle of poverty and deprivation. Environmental issues and land sovereignty were very much on the agenda of indigenous social movements. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People of 2007

] and access to resources to get indigenous people out of a vicious circle of poverty and deprivation. Environmental issues and land sovereignty were very much on the agenda of indigenous social movements. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People of 2007 was celebrated as a major success of campaigners on behalf of first nations.104

was celebrated as a major success of campaigners on behalf of first nations.104

Environmental Movements

Protecting indigenous people and the environment often went hand in hand in the struggle of indigenous social movements. Environmental movements more generally became strong as a response to the destruction wreaked upon nature by the advances of industrial capitalism in the 19th century.105 In the 20th century it became a global phenomenon. Like many social movements, the environmental movement frequently addressed the state in its demands to protect the environment and yet from early on its activists connected across nation-state borders. The environmental movement comprised a range of movements from bird protection to anti-nuclear campaigning that often saw themselves as distinct movements with precious few ties to each other. Like with many of the other movements that are surveyed in this article, postcolonial critiques of them have chipped away at their universal claims arguing at worst that environmentalism has been yet another western-centric imposition on the global south. The internationalism of environmentalism is represented by a range of international groups such as Greenpeace , Friends of the Earth, World Wildlife Fund, Flora and Fauna that organize across countries. Some movements, such as the ones for animal protection go back to the 18th century, but the internationalization of environmentalist movements no doubt accelerated after 1970, even if we already have intense debates by early environmental movements in the global north around 1900.106 Some of the movements have an extraordinary longevity. Thus, for example, the Chipko movement in the north Indian state of Uttarakhand has attempted to save the forests in this part of the Himalayas from deforestation

, Friends of the Earth, World Wildlife Fund, Flora and Fauna that organize across countries. Some movements, such as the ones for animal protection go back to the 18th century, but the internationalization of environmentalist movements no doubt accelerated after 1970, even if we already have intense debates by early environmental movements in the global north around 1900.106 Some of the movements have an extraordinary longevity. Thus, for example, the Chipko movement in the north Indian state of Uttarakhand has attempted to save the forests in this part of the Himalayas from deforestation stretching back to the days of the East India Company who sought to sell contracts to entrepreneurs exploiting the forests thus setting them on a collision course with the native population of the forests who depended on them for their livelihoods.107

stretching back to the days of the East India Company who sought to sell contracts to entrepreneurs exploiting the forests thus setting them on a collision course with the native population of the forests who depended on them for their livelihoods.107

Terrorist Movements

Many of the international social movements before 1945 had to ask themselves how far they wanted to go in pursuit of their specific aims. Should they stick to the legal frameworks set by states and international legal agreements and restrict themselves to peaceful and non-violent protests, or was it justified to use violence? Terrorism, whilst in itself not a social movement, sometimes accompanied and grew out of social movements.108 It was historically associated both with right-wing and left-wing social movements and was linked with religious fundamentalism and anti-imperialism. Like many social movements terrorism addressed, first and foremost, state power, although we have also witnessed a distinct internationalization and globalization of terrorism over time. State action was often crucial in radicalizing social movements to such an extent that they ultimately took recourse to violence. Where social movements were forced underground and persecuted, they were much more likely to turn to violent means. The anarcho-syndicalist labour movement in highly authoritarian states, such as the Romanov empire in Russia before 1914, is a good example of this.109 After the First World war, diverse radical right-wing social movements resorted to terrorist means to destabilize democracies and promote nationalism, anti-Bolshevism and anti-Semitism.110 From the mid-1930s anti-colonial movements chose terrorism in order to achieve their aims of national self-liberation.111

and anti-Semitism.110 From the mid-1930s anti-colonial movements chose terrorism in order to achieve their aims of national self-liberation.111

Conclusion

Many of the anti-colonial movements were inspired by and committed to anarcho-syndicalist ideas.112 It is one of many examples of how international social movements were interconnected. Activists in one movement often became active on behalf of other movements. Different movements shared, at least in parts, the same ambitions and identities, e.g. the proletarian women's movement and the labour movement. Hence it makes sense to study social movements not in isolation but in their intersectionality and interdependency.113 Participation in social movements is often fluid and geared towards forms of self-identification that go beyond a single issue. Commitment to the emancipation of women could go hand in hand with commitment to the cause of workers, of environmental protection, of LGBTQ and indigenous rights. Shared identifications, often emerging from a sense of oppression and victimization, went across movements, allied movements to one another and saw joint activism. The history of international social movements is full of intersections where their activists meet, join forces for a while, then go their separate ways to realign in different formations. The fluidity of these alliances is characteristic of social movements that lack a fixed structure and clear hierarchies. The variety of different international social movements that I surveyed in this survey article need to be brought more into relation to each other rather than just studied separately. If this is done in transnational perspective, it will be possible to see, at one and the same time, how they have been both an expression of universal ambitions and highly space- and time-dependent phenomena.

Such intersectionality of social movements has gained considerable attention in social science research on social movements.114 It needs, however, to be further investigated in historical research on pre-1945 movements which remain understudied. Let me, by way of conclusion, address a few more desiderata in the study of international social movements in the period before the end of the Second World War. First, the assumed divide between premodern and modern social movements, still strong in social movement studies, can only be questioned more systematically if we have more studies on social movements that go deeper into historical terrain than social movement studies have been willing to do in the past. Secondly, another prominent distinction in social movement studies, that between 'new' and 'old' social movements needs more systematic questioning. Thirdly, the study of social movements before 1945 should turn its attention to right-wing social movements, including nationalist and fascist movements that have been neglected in comparison with left-wing movements. Fourthly, studying social movements transnationally will allow the field to move away from its concern with national frames and pave the way to a greater recognition that most social movements have been international ones long before 1945 even if they did not yet have international ways of organizing (although in many cases they had that too – both the socialist and the women's movements testify to that). International moments of social movements can also only be identified in more transnational studies. Fifthly, the arsenal of theories with which to understand the emergence and development of social movements needs to be developed further. The empirical study of social movements should not so much confirm the theories but rather theories should help understand why at certain places and times social movements were more or less successful in mobilizing citizens and achieving their goals. Postcolonialism, theories of past futures, the history of emotions, memory history and media history, as I suggested above, have a lot to offer here. Overall, this brief survey of international social movements before 1945 demonstrates the huge potential of studying their histories in order to shed light on international and global historical processes that transcended the nation state.

Stefan Berger

Appendix

Online Sources

Beissinger, Mark et al. (eds.): Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics. URL: https://www.cambridge.org/core/series/cambridge-studies-in-contentious-politics/9E36E5B5DA387DA74D92E8F1F7E96DAA [2022-08-22]

Berger, Stefan et al. (eds.): Palgrave Studies in the History of Social Movements. URL: https://www.springer.com/series/14580 [2022-08-22]

Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen: Analysen zu Demokratie und Zivilgesellschaft. URL: http://forschungsjournal.de/ [2022-08-22]

Institut für Protest- und Bewegungsforschung. URL: https://protestinstitut.eu/ [2022-08-22]

Institute for Social Movements, in: House for the History of the Ruhr, Ruhr University Bochum. URL: http://www.isb.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/isb/index.html.en [2022-08-22]

Interface: A journal for and about social movements. URL: https://www.interfacejournal.net/archives/issues/ [2022-08-22]

International Religious and Humanitarian Movements, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz. URL: http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/transnational-movements-and-organisations/international-religious-and-humanitarian-movements [2022-08-22]

Johnston, Hank (ed.): The Mobilization Series on Social Movements, Protest, and Culture. URL: https://www.routledge.com/The-Mobilization-Series-on-Social-Movements-Protest-and-Culture/book-series/ASHSER1345 [2022-07-18]

Le Mouvement Social: List of issues. URL: http://www.lemouvementsocial.net/en/list-issues/ [2022-08-22]

Moving the Social: Journal of Social History and the History of Social Movements: About the Journal, in: Ruhr Universität Bochum. URL: https://moving-the-social.ub.rub.de/index.php/MTS/about [2022-08-22]

Social Movement Studies: List of issues, in: Taylor & Francis Online. URL: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/csms20 [2022-08-22]

Literature

Anderson, Benedict: Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London 1983.

Anderson, Bonnie S.: Joyous Greetings: The First International Women's Movement, 1830–1860, Oxford 2000.

Aydin, Cemil: The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia: Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought, 1882–1945, New York 2007. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/aydi13778 [2022-08-22]

Bader-Zaar, Birgitta: Abolitionism in the Atlantic World: The Organization and Interaction of Anti-Slavery Movements in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2011-12-09. URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/baderzaarb-2010-en URN: urn:nbn:de:0159-2011120524 [2022-08-22]

Bauerkämper, Arnd: Transnational Fascism: Cross-Border Relations Between Regimes and Movements in Europe, 1922–1939, in: East-Central Europe 2–3 (2010), pp. 214–246. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/187633010X534469 [2022-08-22]

Baumgarten, Britta et al. (eds.): Conceptualizing Culture in Social Movement Research, Basingstoke 2014. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137385796 [2022-08-22]

Beales, A. C. F.: The History of Peace: A Short Account of the Organized Movements for International Peace, London 1931.

Belmonte, Laura A.: The International LGBT Rights Movement: A History, London 2020.

Berger, Stefan et al. (eds.): Nationalizing Empires, Budapest 2015. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctt16rpr1r [2022-08-22]

Berger, Stefan / Nehring, Holger: Introduction: Towards a Global History of Social Movements, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective. A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 1–36. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_1 [2022-08-22]

Berger, Stefan: Labour Movements in Global Historical Perspective: Conceptual Eurocentrism and Its Problems, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.), The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 385–418. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_14 [2022-08-22]

Berger, Stefan et al. (eds.): Remembering Social Movements: Activism and Memory, London 2021. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003087830 [2022-08-22]

Berger, Stefan et al. (eds.): Rethinking Revolutions between 1905 and 1934: Democracy, Social Justice and National Liberation around the World, Basingstoke 2022.

Blickle, Peter: Unruhen in der ständischen Gesellschaft: 1300–1800, Munich 1988.

Borch, Christian: The Politics of Crowds: An Alternative History of Sociology, Cambridge 2012. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511842160 [2022-08-22]

Bouchard, Gérard: Genèse des nations et cultures du nouveau monde, Montreal 2000.

Breuilly, John (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism, Oxford 2013.

Brooker, Russell: The American Civil Rights Movement, 1865–1950: Black Agency and People of Good Will, Lanham, MD 2017.

Calhoun, Craig: The Roots of Radicalism: Tradition, the Public Sphere and Early Nineteenth-Century Social Movements, Chicago 2012.

Calhoun, Craig: New Social Movements of the Early Nineteenth Century, in: Social Science Journal 17 (1993), pp. 385–427. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/1171431 [2022-08-22]

Chakrabarty, Dipesh: Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, new ed., Princeton 2008. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7rsx9 [2022-08-22]

Cho, Sumi et al. (eds.): Intersectionality: Theorizing Power, Empowering Theory, in: Signs 38, 4 (2013), pp. 785–1060. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/669610 [2022-08-22]

Cohn Jr., Samuel K. (ed.): Popular Protest in Late Medieval Europe, Manchester 2004. URL: https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526112767 [2022-08-22]

Cooper, Sandi E.: Patriotic Pacifism: Waging War on War in Europe, 1815–1914, Oxford 1991.

Cortright, David: Peace: A History of Movements and Ideas, Cambridge 2008.

Cox, Jeffrey: The British Missionary Enterprise since 1700, London 2008.

Della Porta, Donatella / Diani, Mario: Social Movements: An Introduction, 3rd ed., Oxford 2020.

Della Porta, Donatella et al. (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements, Oxford 2015. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199678402.001.0001 [2022-08-22]

Della Porta, Donatella et al. (eds.): Transnational Protest and Global Activism: People, Passions and Power, Lanham, MD 2005.

Downing, John D. H. (ed.): Encyclopedia of Social Movement Media, London 2011.

Eckert, Andreas: Social Movements in Africa, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 211–224. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_8 [2022-08-22]

Eckstein, Susan: Power and Popular Protest: Latin American Social Movements, Berkeley 1989. URL: https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520352148 [2022-08-22]

Eley, Geoff: Forging Democracy: The History of the Left in Europe, 1850–2000, Oxford 2002.

English, Richard: Irish Freedom: The History of Nationalism in Ireland, London 2006.

Eyerman, Ron: Social Movements and Memory, in: Anna Lisa Tota et al. (eds.), Routledge International Handbook of Memory Studies, London 2015, pp. 79–83. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203762844 [2022-08-22]

Ferree, Myra Marx et al. (eds.): Global Feminism: Transnational Women's Activism, Organizing and Human Rights, New York 2006.

Fillieule, Olivier et al. (eds.): Social Movement Studies in Europe: The State-of-the-Art, Oxford 2016. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvgs0c35 [2022-08-22]

Flesher Fominaya, Cristina et al. (eds.): Understanding European Movements: New Social Movements, Global Justice Struggles, Anti-Austerity Protest, London 2013. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203083710 [2022-08-22]

Frevert, Ute (ed.): Moral Economies, Göttingen 2019.

Gamson, William / Wolfsfeld, Gadi: Movements and Media as Interacting Systems, in: Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 528 (1993), pp. 114–125. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1047795 [2022-08-22]

Gerwarth, Robert / Horne, John: The Great War and Paramilitarism in Europe, 1917–1923, in: Contemporary European History 19 (2010), pp. 267–273. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20749813 [2022-08-22]

Goodwin, Jeff et al. (eds.): Passionate Politics: Emotions and Social Movements, Chicago 2001. URL: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226304007.001.0001 [2022-08-22]

Green, Abigail et al. (eds.): Religious Internationals in the Modern Age: Globalization and Faith Communities since 1750, Basingstoke 2012. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137031716 [2022-08-22]

Guha, Ranajit: Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India, Oxford 1983.

Gutman, Yifat et al. (eds.): Handbook on Memory Activism, London 2022 [forthcoming].

Haimson, Leopold et al. (eds.): Strikes, Social Conflict and the First World War: An International Perspective, Milano 1992.

Haliczer, Stephen: The Comuneros of Castile: The forging of a revolution, 1475–1521, Madison, WI 1981.

Hall, Stuart: Introduction: Who Needs Identity?, in: Stuart Hall et al. (eds.): Questions of Cultural Identity, London 1996, pp. 1–17. URL: https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446221907.n1 [2022-08-22]

Heath, Dwight B. (ed.): International Handbook on Alcohol and Culture, Westport, CT 1995.

Hilton, Rodney: Bond Men Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381, London 2005. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203426654 [2022-08-22]

Hirsch, Steven et al. (eds.): Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870–1940: The Praxis of National Liberation, Internationalism and Social Revolution, Leiden 2010. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004188495.i-432 [2022-08-22]

Hirschhausen, Ulrike von et al. (eds.): Nationalismen in Europa: West- und Osteuropa im Vergleich, Göttingen 2001. URL: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:25-opus-32541 [2022-08-22]

Hobsbawm, Eric: The Age of Revolution 1789–1848, London 1962.

Hobsbawm, Eric: Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Manchester 1959.

Hölscher, Lucian (ed.): Die Zukunft des 20. Jahrhunderts: Dimensionen einer historischen Zukunftsforschung, Frankfurt am Main 2017.

Hölscher, Lucian: Die Entdeckung der Zukunft, Göttingen 2016.

Hölscher, Lucian: Weltgericht oder Revolution: Protestantische und sozialistische Zukunftsvorstellungen im deutschen Kaiserreich, Munich 1989.

Hoffmann, Stefan-Ludwig: Human Rights in the Twentieth Century, Cambridge 2011. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511921667 [2022-08-22]

Jefferies, Matthew et al. (eds.): Rolf Gardiner: Folk Nature and Culture in Interwar Britain, London 2016.

Jones, Kenneth: Socio-Religious Reform Movements in British India, Cambridge 1989. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521249867 [2022-08-22]

Katalja, Kimmo (ed.): Northern Revolts: Medieval and Early Modern Peasant Unrest in the Nordic Countries, Helsinki 2004.

Keck, Margaret E. / Sikkink, Kathryn: Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics, Ithaca 1998. URL: https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801471292 [2022-08-22]

Klönne, Arno: Es begann 1913: Jugendbewegung in der deutschen Geschichte, Erfurt 2013.

Konieczna, Anna et al. (eds.): A Global History of Anti-Apartheid: 'Forward to Freedom' in South Africa, Basingstoke 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03652-2 [2022-08-22]

Koselleck, Reinhart: Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time, New York 2004. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/kose12770 [2022-08-22]

Kumar, Raj (ed.): Essays on Social Reform Movements, New Delhi 2004.

Lee, Namhee: The Making of Minjung: Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea, Ithaca 2009. URL: https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801461699 [2022-08-22]

Lenz, Ilse: Equality, Difference and Participation: The Women's Movements in Global Perspective, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 449–484. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_16 [2022-08-22]

Linden, Marcel van der: European Social Protest, 1000–2000, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 175–210. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_7 [2022-08-22]

Linden, Marcel van der: Workers of the World: Essays Toward a Global Labour History, Leiden 2008.

Löhr, Isabella: The League of Nations, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2015-08-17. URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/loehri-2015-en URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0159-2015081717 [2022-08-22]

Lovell, Stephen (ed.): Generations in Twentieth-Century Europe, Basingstoke 2007.

Lucassen, Jan (ed.): Global Labour History: A State of the Art, Berne 2006.

Lüdke, Tilman: Pan-Ideologies, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2012-03-06. URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/luedket-2012-en URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0159-20110201189 [2022-08-22]

Lynch, Cecelia: Beyond Appeasement: Interpreting Interwar Peace Movements in World Politics, Ithaca 1999.

Majumdar, Rochona: Subaltern Studies as a History of Social Movements in India, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 63–92. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_3 [2022-08-22]

McAdam, Doug et al. (eds.): Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements Political Opportunities, Mobilizing Structures and Cultural Framings, Cambridge 1996. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803987 [2022-08-22]

McConnell, D. W.: "Temperance Movements", in: Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences 14 (1963), pp. 567–570.

Mittag, Jürgen et al. (eds.): Theoretische Ansätze und Konzepte der Forschung über soziale Bewegungen in der Geschichtswissenschaft, Essen 2014.

Möller, Esther: Red Cross and Red Crescent, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2020-12-07. URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/moellere-2020-en URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0159-2020113005 [2022-08-22]

Mollat, Michel / Wolff, Philippe: The Popular Revolutions of the Late Middle Ages, London 1973. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003225980 [2022-08-22]

Mousnier, Roland: Peasant Uprisings in Seventeenth-Century France, Russia and China, London 1970. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003194774 [2022-08-22]

Mudde, Cas: The Far Right Today, Cambridge 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00157-5 [2022-08-22]

Nehring, Holger: Peace Movements, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 485–514. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_17 [2022-08-22]

Neidhardt, Friedhelm: Einige Ideen zu einer allgemeinen Theorie sozialer Bewegungen, in: Stefan Hradil (ed.): Sozialstruktur im Umbruch: Karl Martin Bolte zum 60. Geburtstag, Opladen 1985, pp. 193–204. URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-95501-2_12 [2022-08-22]

Nepstad, Sharon Erickson: Catholic Social Activism: Progressive Movements in the United States, New York 2019. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv12fw5xr [2022-08-22]

Ness, Immanuel et al. (eds.): The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism, vol. 1–2, Basingstoke 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230392786 [2022-08-22]

Neubauer, John: The Fin-de-Siècle Cultures of Adolescence, New Haven 1992.

Nunez-Seixas, Xose Manoel: History of Civilization: Transnational or Postimperial? Some Iberian Perspectives (1870–1930), in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): Nationalizing the Past: Historians as Nation Builders in Modern Europe, Basingstoke 2010, pp. 384–403. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230292505_19 [2022-08-22]

Offen, Karen: European Feminisms, 1700–1950: A Political History, Stanford 2000. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804764162 [2022-08-22]

Olejniczak, Claudia: Die Dritte-Welt Bewegung in Deutschland: Konzeptionelle und organisatorische Strukturmerkmale einer neuen sozialen Bewegung, Wiesbaden 1998. URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-08195-1 [2022-08-22]

Opp, Karl-Dieter: Theories of Political Protest and Social Movements: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, Critique and Synthesis, London 2009. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203883846 [2022-08-22]

Park, Senjoo: Transpacific Feminism: Writing Women's Movement from a Transnational Perspective, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 93–112. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_4 [2022-08-22]

Parsons, Elaine Frantz: Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan during Reconstruction, Chappel Hill 2015. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469625430_parsons [2022-08-22]

Passmore, Kevin: Fascism as a Social Movement in a Transnational Context, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 579–618. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_20 [2022-08-22]

Peel, Dan (ed.): The History of the Civil Rights Movement: The Story of the African-American Fight for Justice and Equality, Solihull 2021.

Pliley, Jessica et al. (eds.): Global Anti-Vice Activism, 1890–1950: Fighting Drinks, Drugs and 'Immorality', Cambridge 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316212592 [2022-08-22]

Przyrembel, Alexandra: From Cultural Wars to the Crisis of Humanity: Moral Movements in the Modern Age, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 355–384. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_13 [2022-08-22]

Ramstedt, Otthein: Soziale Bewegung, Frankfurt am Main 1978.

Rice, Robert: The New Politics of Protest: Indigenous Mobilization in Latin America's Neoliberal Era, Tucson 2012. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt181hxtw [2022-08-22]

Rigney, Ann: Remembering Hope: Transnational Activism Beyond the Traumatic, in: Memory Studies 11, 3 (2018), pp. 368–380. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1750698018771869 [2022-08-22]

Rogers, John D.: Cultural Nationalism and Social Reform: The 1904 Temperance Movement in Sri Lanka, in: The Indian Economic and Social History Review 26, 3 (1989), pp. 312–339. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F001946468902600303 [2022-08-228]

Rootes, Christopher (ed.): Environmental Movements: Local, National and Global, London 2014.

Rosas, João Cardoso et al. (eds.): Left and Right: The Great Dichotomy Revisited, Newcastle upon Tyne 2013.

Roseman, Mark (ed.): Generations in Conflict: Youth Revolt and Generation Formation in Germany 1770–1968, Cambridge 2004. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511562761 [2022-08-22]

Rother, Bernd: The Socialist International, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2018-02-15. URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/rotherb-2012-en URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0159-2018021307 [2022-08-22]

Rucht, Dieter: Studying Social Movements: Some Conceptual Challenges, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.): The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 39–62. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-30427-8_2 [2022-08-22]

Rucht, Dieter: Neue soziale Bewegungen – Anwälte oder Irrläufer des Projekts der Moderne?, in: Frankfurter Hefte 11–12 (1984), pp. 144–149. URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/122440 [2022-08-22]