Introduction

The notion of pilgrimage refers to all kinds of spiritually charged journeys, usually toward specific places of worship (shrines) that pilgrims view as being imbued with the presence of the divine or some other extraordinary power. The word "pilgrimage" thus designates a remarkable variety of practices that are prominent within most religious traditions across the globe.1 Historically and up to the present day, pilgrims' motivations have varied widely – from the ascetic to the recreational, from the penitential to the political. A few religious scriptures and authorities have prescribed pilgrimage, while others have recommended or merely tolerated the practice. Some historically common pilgrimages were day trips.2 Many other pilgrims used to take weeks or months to reach their destinations, such as Catholics from north of the Alps traveling to Rome or Santiago de Compostela, or European Muslims making the hajj to Mecca.

In short, pilgrimage is an expansive phenomenon both spatially and conceptually. The best-known pilgrimage tradition – the 'Western' or Roman Catholic one – cannot represent all of European pilgrimage in pars pro toto fashion. Hence, this entry aims to do justice to the sheer diversity of pilgrimage practices in which early modern and modern Europeans engaged. It discusses how mobility and communication coalesced in European pilgrimages, and it focuses on the ways that pilgrimage linked holy places to each other across political and cultural boundaries. Finally, treating pilgrims and pilgrimage promoters as agents of cultural transfer involves taking seriously the entanglements between various churches and faiths that often occurred at and around shrines.

In other words, this entry aims to shed light on pilgrimage as a transcultural practice, rather than to sketch a general history of European pilgrimage from the Reformation era to the present. Most of the evidence presented below comes from the 17th through 19th centuries. This emphasis makes it possible to consider how pilgrimage interacted with crucial developments of both the early modern and modern eras, including confessional identity formation, intensifying imperialism, industrialization, and the rise of nationalism.

European Pilgrimage Traditions and Their Major Shrines

The easiest way to highlight the importance of early modern and modern pilgrimage is to insist on its impressive quantitative dimensions. Some caveats are admittedly in order. On the European scale, we lack comprehensive statistics about numbers of shrines and overall movement of pilgrims. Moreover, the geography of pilgrimage never coalesced into a static, easily measurable pattern. The fortunes of individual shrines waxed and waned. On the whole, however, it is quite likely that in any given year, tens of millions of people were on the move as pilgrims throughout Europe, whether merely for a couple of days or for several months. If the Middle Ages have nonetheless been considered "the" age of Christian pilgrimage,3 the underlying assumption of post-medieval decline applies almost exclusively to majority-Protestant parts of Europe.4 Catholic and Orthodox pilgrimage has flourished more often than not since the Reformation era; in addition, Jewish and Muslim pilgrims have played significant parts on a diverse European scene.

Among the largest confessional group, Roman Catholics, both long- and short-distance pilgrimages were strikingly common endeavors during the Baroque era (the mid-16th to mid-18th centuries) as well as afterwards.5 Of the three most prestigious destinations, while Ottoman-ruled Jerusalem had become hard to access for Catholics by the 16th century, Rome remained heavily frequented by pilgrims; Santiago de Compostela continued to fare very well, too, except for approximately a century following the French Revolution.6 For instance, Rome may have received as many as 350,000 to 400,000 pilgrims during each of the Holy Years of 1575, 1600, 1625, and 1650, and probably between 200,000 and 300,000 in each of the 18th- and early-19th-century Holy Years.7 Other pilgrimage jubilees and rare showings of relics – such as the once-in-a-generation showings of the Holy Coat of Jesus

had become hard to access for Catholics by the 16th century, Rome remained heavily frequented by pilgrims; Santiago de Compostela continued to fare very well, too, except for approximately a century following the French Revolution.6 For instance, Rome may have received as many as 350,000 to 400,000 pilgrims during each of the Holy Years of 1575, 1600, 1625, and 1650, and probably between 200,000 and 300,000 in each of the 18th- and early-19th-century Holy Years.7 Other pilgrimage jubilees and rare showings of relics – such as the once-in-a-generation showings of the Holy Coat of Jesus in Trier – constituted mass events as well, frequently leaving durable marks on devotional culture

in Trier – constituted mass events as well, frequently leaving durable marks on devotional culture and the politics of religion on a transregional scale.8 More steadily and no less remarkably, a large handful of Catholic shrines were visited by more than 100,000 pilgrims per year. At the height of the Baroque, these destinations included Loreto in Italy, Montserrat in Catalonia, Liesse in France, Einsiedeln in Switzerland, Kevelaer, Walldürn, and Altötting in present-day Germany, Mariazell in Austria, and Jasna Góra in Poland.9 Almost all of these were Marian shrines, as was the most famous modern apparition site, that of Lourdes in the French Pyrenees

and the politics of religion on a transregional scale.8 More steadily and no less remarkably, a large handful of Catholic shrines were visited by more than 100,000 pilgrims per year. At the height of the Baroque, these destinations included Loreto in Italy, Montserrat in Catalonia, Liesse in France, Einsiedeln in Switzerland, Kevelaer, Walldürn, and Altötting in present-day Germany, Mariazell in Austria, and Jasna Góra in Poland.9 Almost all of these were Marian shrines, as was the most famous modern apparition site, that of Lourdes in the French Pyrenees  .10 Small and mid-sized shrines also proliferated immensely during the Baroque.11

.10 Small and mid-sized shrines also proliferated immensely during the Baroque.11

In eastern and southeastern Europe, Orthodox shrines constituted key spiritual and cultural hubs. In Greece, Mount Athos is situated on a somewhat remote peninsula and its monastic inhabitants did not (and still do not) accept any female visitors

and its monastic inhabitants did not (and still do not) accept any female visitors , but many thousands of men from all over the Balkans as well as from faraway Russia traveled there each year. Between the 1850s and the October Revolution of 1917, Mount Athos even experienced a "pilgrimage boom".12 Above all, the Tsarist mass emancipation of serfs in the mid-19th century unintentionally enabled a great increase in pilgrim mobility among the rural population of the Russian Empire. Within the empire's own territory, arguably the foremost sacred site to benefit from this development was the Kyiv Caves Monastery (Pechersk-Lavra)

, but many thousands of men from all over the Balkans as well as from faraway Russia traveled there each year. Between the 1850s and the October Revolution of 1917, Mount Athos even experienced a "pilgrimage boom".12 Above all, the Tsarist mass emancipation of serfs in the mid-19th century unintentionally enabled a great increase in pilgrim mobility among the rural population of the Russian Empire. Within the empire's own territory, arguably the foremost sacred site to benefit from this development was the Kyiv Caves Monastery (Pechersk-Lavra) , which received more than 200,000 pilgrims annually in the decades after 1860.13 Already before 1800, the Caves Monastery had attracted great numbers of Orthodox as well as Uniate (Eastern Catholic) pilgrims from Polish-dominated parts of present-day Ukraine, and had generated interest among writers from even further west.14 Similarly famous shrines in northwestern Russia included the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius near Moscow and the Solovetsky Monastery located on an island in the White Sea.15

, which received more than 200,000 pilgrims annually in the decades after 1860.13 Already before 1800, the Caves Monastery had attracted great numbers of Orthodox as well as Uniate (Eastern Catholic) pilgrims from Polish-dominated parts of present-day Ukraine, and had generated interest among writers from even further west.14 Similarly famous shrines in northwestern Russia included the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius near Moscow and the Solovetsky Monastery located on an island in the White Sea.15

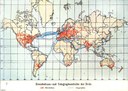

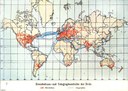

Muslim pilgrimage was a European phenomenon to a significant extent, already long before Muslims came to constitute sizeable minorities in western countries such as the UK, France, and Germany. Of course, Islam's foremost and prescribed sacred destination, Mecca, lies outside the geographical boundaries of Europe – as does Jerusalem, for that matter. That said, in the 18th and 19th century, large Muslim populations came under the imperial rule of European powers. This process occurred in British India (especially after 1757) and Egypt (1882), French Algeria (1830) , and Austrian Bosnia and Herzegovina (1878); above all, around 1900, roughly 20 million Muslims were subjects of the Russian Tsar, and a large percentage of them lived in European areas such as Crimea, the plains around the Volga River, and the Caucasus region.16 Whilst European governments oscillated between attempts to repress, control, or co-opt the hajj, European Muslims seized the opportunities created by modern infrastructure – the Suez Canal, railroads, steamship lines – that effectively made Mecca much more accessible. The annual number of Muslims going on the hajj thus tripled from roughly 100,000 to 300,000 over the course of the 19th century.17 Moreover, regionally important Islamic pilgrimages existed (and continue to exist) on the European continent itself, such as the yearly Ajvatovica gatherings in the Bosnian village of Prusac.18

, and Austrian Bosnia and Herzegovina (1878); above all, around 1900, roughly 20 million Muslims were subjects of the Russian Tsar, and a large percentage of them lived in European areas such as Crimea, the plains around the Volga River, and the Caucasus region.16 Whilst European governments oscillated between attempts to repress, control, or co-opt the hajj, European Muslims seized the opportunities created by modern infrastructure – the Suez Canal, railroads, steamship lines – that effectively made Mecca much more accessible. The annual number of Muslims going on the hajj thus tripled from roughly 100,000 to 300,000 over the course of the 19th century.17 Moreover, regionally important Islamic pilgrimages existed (and continue to exist) on the European continent itself, such as the yearly Ajvatovica gatherings in the Bosnian village of Prusac.18

In Judaism, pilgrimage had been rendered apparently obsolete with the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD. Medieval and early modern European rabbis and Jewish merchants, however, sometimes went on individual journeys to Jerusalem and other spiritually important places in Palestine. The emergence of Zionism added a new layer to this kind of travel. From 1890 to 1914, nine Jewish "convoys" of between nine and 150 Zionist leaders and activists journeyed from different parts of Europe to Eretz Israel (the land of Israel) and back again. Participants in these trips pursued not just spiritual fulfillment but also national identity formation, contacts with Jewish inhabitants of Palestine, and touristic curiosity; yet, the best-known of the convoys, that of 1897, was named "The Pilgrimage Journey of the Maccabean Group to the Holy Land" by the group's leader Herbert Bentwich (1856–1932).19 Within Europe, rising Hasidism in the 18th and 19th centuries established a sacred topography of its own, as Jews adhering to the movement made pilgrimages to the gravesites of important leaders (rebbes) such as Elimelech of Lizhensk (1717–1787) and Nachman of Breslov (1772–1810).20

Pilgrim Mobility: Patterns, Constraints, and Experiences

Pilgrimage stimulated cultural encounters and exchanges in part because it involved large-scale mobility of people. As the previous section has suggested, there can be hardly any doubt that the practice was highly popular. It represented a distinct form of movement, frequently across great distances, for male as well as female members of all social strata. Yet, different people experienced pilgrimage rather differently, not least because pilgrim communities were partly structured along the lines of class (or social rank) and gender. In various periods and regions, pilgrims also faced mounting obstacles on their journeys, including state-led securitization and campaigns to restrict religious mobility.

Many scholars have categorized Christian pilgrimage as a quintessential expression of "popular piety", though some of them have used the word 'popular' to refer to the laity – which includes members of social elites such as lay nobles – rather than to the popular classes.21 In spite of the conceptual pitfalls, it is important to emphasize that a large percentage of long- as well as short-distance pilgrims were poor, across the centuries and throughout Europe. In the early modern period, as before in the Middle Ages, indigent pious travelers relied on alms and an extensive network of hospitals, situated along major routes and in the towns where shrines were located.22 After 1850, railroad infrastructure made pilgrimage more affordable for many.23 Meanwhile, parts of the bourgeoisie and, to a lesser extent, the nobility in Roman Catholic countries came to adhere to the Enlightenment or (later on) liberalism, consequently losing interest in pilgrimage.24 Some of these 'enlightened' elites even imagined that only a poor and ignorant populace continued to indulge in such a supposedly superstitious and unproductive endeavor as pilgrimage.25

made pilgrimage more affordable for many.23 Meanwhile, parts of the bourgeoisie and, to a lesser extent, the nobility in Roman Catholic countries came to adhere to the Enlightenment or (later on) liberalism, consequently losing interest in pilgrimage.24 Some of these 'enlightened' elites even imagined that only a poor and ignorant populace continued to indulge in such a supposedly superstitious and unproductive endeavor as pilgrimage.25

Thus, by 1800, pilgrimage became culturally coded as a rather plebeian practice – even though, in reality, the wealthy and the high-born kept engaging in it as well. Indeed, their experiences often received more attention than those of other pilgrims, and at least in the early modern period, royal and princely pilgrimages often took the shape of particularly pompous processions, representing a distinct kind of ostentatious mobility.26 Rank could also determine the micro-management of access and mobility at shrines themselves. At the Kyiv Caves Monastery, for instance, monks tended to offer elaborate guided tours through the various subterranean churches only to members of the Tsar's family and other elite pilgrims.27

Analogous and overlapping with pilgrimage by the poor, female pilgrim mobility was a widespread phenomenon that has tended to grow in both absolute and relative terms in recent centuries, while also being at times ridiculed or exaggerated and at other times erased or marginalized. It does seem that early modern long-distance pilgrimage was predominantly practiced by young, unmarried men. In Catholic parts of Germany and some other regions, however, it was not uncommon for women to undertake long pilgrim journeys together with their husbands and children.28 According to the miracle books of smaller, regionally important shrines, female pilgrims made up roughly half – and in some cases significantly more than half – of the people who reported miraculous healings.29 In the Kulturkampf times of the 19th century, when Roman Catholicism acquired the reputation of being a "feminized" religion, women often appeared as typical pilgrims . That said, blanket assumptions about a decline in either male participation or male pilgrims' fervor are unwarranted.30 In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, female pilgrims were likewise numerous and quite possibly in the majority by the later 19th century, at least at the Caves Monastery.31

. That said, blanket assumptions about a decline in either male participation or male pilgrims' fervor are unwarranted.30 In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, female pilgrims were likewise numerous and quite possibly in the majority by the later 19th century, at least at the Caves Monastery.31

As for the hajj, women – and especially non-elite women – long tended to be just as underrepresented among pilgrims as they were in Christian long-distance pilgrimage. Many Islamic legal scholars argued that women were neither allowed nor truly obligated to go on the hajj unless they had a husband or other mahram (male guardian) who was willing to accompany them. Nevertheless, by the mid-20th century when gendered statistics for the hajj first became available, women formed a large and growing minority among pilgrims at Mecca.32

Across lines of class and gender, pilgrim mobility was frequently affected by warfare, political upheavals, and legal hurdles as well. In this regard, the 18th and 19th centuries arguably form a unified and particularly important period, during which many European states enacted heavy-handed methods of policing pilgrimage. For one thing, the policing of worship in general (police du culte in French, Religionspolizei in German) intensified. This process took place across Europe as state apparatuses struggled to secure their ascendancy vis-à-vis the Catholic and Orthodox churches, but also in the Middle East and North Africa where European powers gained a distinct imperial foothold in the 19th century.33 At the same time, state authorities were aiming at "monopolizing the legitimate means of movement" through passport regulations and harsh crackdowns on real or imagined populations of vagrants.34 Meanwhile, as mentioned above, the numerous detractors of pilgrimage decried it as an amalgam of (primarily feminine) 'superstition' and (popular) 'vagabondage.' As a result, pilgrims found themselves in an unenviable spot where the policing of worship intersected with the policing of mobility. Such challenges disrupted pious travels and temporarily diminished some flows of long-distance pilgrim mobility.35 In many cases, however, pilgrims came up with powerful responses to crisis: people practiced pilgrimage with greater urgency and effectively turned it into a border-crossing, often transnational or transimperial provocation.36

Communicative and Visual Dimensions

Pilgrims engaged in divergent forms of communication, ranging from the transcendent to the mundane, from silent prayers to elaborate public liturgies to sensationalist advertising, from enthusiastic reports to extremely hostile commentaries.37 Pilgrimage feasts typically involved multisensory ritual spectacles. At and around shrines, pious travelers also encountered a stunning array of devotional objects – images, rosaries, books, bottles filled with holy water, and so much more – that they purchased and often shared with those who had stayed home.38 Textual, oral, visual, and other non-verbal forms of communication were thus deeply interwoven with pilgrim mobility and underpinned the cultural exchanges facilitated by religious practice.

Communication established reputations. Lest one overestimate the power of the written word, it is important to point out how strongly word of mouth influenced the renown of shrines, especially in the early modern period when the majority of pilgrims were illiterate.39 Rumors about miraculous events – healings, apparitions, mysterious discoveries of statues – tended to spread like wildfire. An individual hoping for a specific divine favor, such as a cure for their child's illness, would often seek out an elderly local woman to help decide at which shrine this favor might best be implored.40 Collectively, people cultivated the memory of communal vows and other local customs of pilgrimage.41 For instance, by the time a young man from Lorraine named Félix Marande went on his first pilgrimage to Einsiedeln in 1832, he had long been familiar with elderly women's tales according to which the great Swiss abbey "was like paradise".42 Marande's account also shows how such local traditions became intertwined with a certain European consciousness, as he marveled at "the mixture of all ranks, sexes, and ages, of all the peoples of Europe" who came to Einsiedeln as pilgrims.43

As literacy rates kept growing, shrine books and printed pilgrimage travelogues became important pilgrimage-related media, and in the 19th century, newspaper reports and advertisements began to play prominent roles as well. Shrine books were usually produced by local clergy, who combined pious histories of 'their' respective sacred places with lists and descriptions of the numerous miracles that had occurred there. Hundreds of Roman Catholic pilgrimage destinations came to boast this type of publicity over the course of the early modern period. Shrine books were often meant to enable cultural transfer, specifically by promoting new conceptions of the sacred and new devotional forms favored by the clergy.44 Beginning in the 17th century, these publications also turned into the foundation for regional, European, and even global compendia of Catholic shrines. Such atlases reflected the Roman Church's goal of positioning itself as both a guardian of place-bound sacrality and an increasingly global community.45 Later on, in the age of mass media, the stunning career of Lourdes owed much to breathless newspaper reporting, and after 1900, Muslim newspapers in the Russian Empire likewise offered a great deal of advice and incentives to prospective hajj pilgrims.46

Cultural innovation and transnational entanglements also crystallized in visual culture as well as architecture. Across early modern Catholic Europe, clergy and local authorities used the considerable income generated by pilgrimage to magnificently enlarge, rebuild , and refurbish

, and refurbish shrines in the Baroque style.47 The reach of this style went beyond Roman Catholicism. In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where a large part of the Eastern Church had entered a union with the papacy in 1595/6, several famous pilgrimage places controlled by the Uniates underwent a decidedly Baroque makeover in the 18th century. Two impressive examples of this trend are the Uniate cathedral of Chełm

shrines in the Baroque style.47 The reach of this style went beyond Roman Catholicism. In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where a large part of the Eastern Church had entered a union with the papacy in 1595/6, several famous pilgrimage places controlled by the Uniates underwent a decidedly Baroque makeover in the 18th century. Two impressive examples of this trend are the Uniate cathedral of Chełm and the Basilian monastery of Pochaiv

and the Basilian monastery of Pochaiv .48 Even international conflict sometimes inscribed itself into sacred space in ways that stimulated pilgrimage and shaped its meanings. For instance, after Solovetsky Monastery had withstood a British naval onslaught

.48 Even international conflict sometimes inscribed itself into sacred space in ways that stimulated pilgrimage and shaped its meanings. For instance, after Solovetsky Monastery had withstood a British naval onslaught during the Crimean War, adding a layer of Russian patriotism to its fame, pilgrims arrived in growing numbers, inspected the bullet holes from the attack, and "crawled over pyramids of cannonballs".49

during the Crimean War, adding a layer of Russian patriotism to its fame, pilgrims arrived in growing numbers, inspected the bullet holes from the attack, and "crawled over pyramids of cannonballs".49

Christian Pilgrimage and Networks of Shrines

In universalistic religious traditions such as Christianity, and particularly in its Catholic variety, cultural transfer has often taken the form of a dialectics between localizing the universal and universalizing the local. Hence why Catholicism since the Council of Trent (1545–63) , for instance, both has and has not been 'Roman.' The push to centralize ecclesiastical power in the Eternal City, codify canon law, and standardize the liturgy has proved strong and durable. Yet, so has the need and even the hierarchy's willingness to accommodate the heterogeneity of complex local settings, attend to impulses coming from the supposed peripheries, and incorporate some of these impulses into the universalist Catholic agenda.50 In this back and forth, pilgrims and pilgrimage promoters have played major roles, fostering transfers and circulation of religious (and other) knowledge through the channels of mobility and communication described above.

, for instance, both has and has not been 'Roman.' The push to centralize ecclesiastical power in the Eternal City, codify canon law, and standardize the liturgy has proved strong and durable. Yet, so has the need and even the hierarchy's willingness to accommodate the heterogeneity of complex local settings, attend to impulses coming from the supposed peripheries, and incorporate some of these impulses into the universalist Catholic agenda.50 In this back and forth, pilgrims and pilgrimage promoters have played major roles, fostering transfers and circulation of religious (and other) knowledge through the channels of mobility and communication described above.

A key pattern of transfer concerned the devotions centered on the Passion of Jesus. They were underwritten by European Catholics' desire to transplant, represent, and re-experience the sites and events of Jesus's redemptive suffering. While replicas of the Holy Sepulcher had dotted Europe since the time of the crusades, the early modern period and the 19th century saw the proliferation of calvaries. The northern Italian Sacri Monti constitute a particularly well-known ensemble of calvaries, but the single most important and large-scale replica of the Stations of the Cross was created in southern Poland, in a place that would evolve into a major pilgrimage destination called Kalwaria Zebrzydowska .51 Here, in the early 1600s, the voivode of Kraków Mikołaj Zebrzydowski (1553–1620) recreated the topography of the Passion true to size – which is to say, through an ensemble of chapels spread across several square kilometers. He based this reconstruction on plans drawn up by Hieronim Strzała (ca. 1555–1620), a nobleman in Zebrzydowski's retinue who had recently made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and on the claim that the hilly terrain he had selected corresponded neatly to that of Jerusalem itself. Zebrzydowski also had a monastery built next to the calvary and entrusted it to the Bernardines, a branch of the Franciscan Order.52 This choice was hardly coincidental, as the Franciscans also controlled the Custody of the Holy Land and promoted the devotion to the via crucis at shrines and in parishes throughout early modern Europe.53 The story of Kalwaria Zebrzydowska thus exemplifies how pilgrim mobility reproduced and reinforced imaginary as well as institutionalized links between (Catholic) Europe and Palestine.

.51 Here, in the early 1600s, the voivode of Kraków Mikołaj Zebrzydowski (1553–1620) recreated the topography of the Passion true to size – which is to say, through an ensemble of chapels spread across several square kilometers. He based this reconstruction on plans drawn up by Hieronim Strzała (ca. 1555–1620), a nobleman in Zebrzydowski's retinue who had recently made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and on the claim that the hilly terrain he had selected corresponded neatly to that of Jerusalem itself. Zebrzydowski also had a monastery built next to the calvary and entrusted it to the Bernardines, a branch of the Franciscan Order.52 This choice was hardly coincidental, as the Franciscans also controlled the Custody of the Holy Land and promoted the devotion to the via crucis at shrines and in parishes throughout early modern Europe.53 The story of Kalwaria Zebrzydowska thus exemplifies how pilgrim mobility reproduced and reinforced imaginary as well as institutionalized links between (Catholic) Europe and Palestine.

The Holy House of Loreto constituted another important, eminently transferable symbol of early modern Catholicism. Portability held a central place in the legend of the Santa Casa, the Virgin Mary's house, which Catholics believed had been transported by angels out of Palestine to Trsat in present-day Croatia and from there eventually to Loreto in the 1290s. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Loreto turned into one of Europe's most celebrated and well-frequented pilgrimage sites, partly due to the intensified emphasis that the Catholic Church was placing on Marian devotion.54 At the same time, the local and the transregional were again inextricably interwoven, as pious Catholics across the continent began to have replicas, so-called Loreto chapels, constructed to signal their alignment with, and contribution to, the Catholic Reformation. Quite a few of these chapels became the sites of reported miracles and developed into pilgrimage churches in their own right – for example, the Holy Houses on the Kobelberg

in the 1290s. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Loreto turned into one of Europe's most celebrated and well-frequented pilgrimage sites, partly due to the intensified emphasis that the Catholic Church was placing on Marian devotion.54 At the same time, the local and the transregional were again inextricably interwoven, as pious Catholics across the continent began to have replicas, so-called Loreto chapels, constructed to signal their alignment with, and contribution to, the Catholic Reformation. Quite a few of these chapels became the sites of reported miracles and developed into pilgrimage churches in their own right – for example, the Holy Houses on the Kobelberg near Augsburg and in Starý Hrozňatov near the Bohemian town of Cheb.55 Lauretan devotion spread to the Americas as well and was embraced by many indigenous people there, thanks not only to Jesuit propaganda but also to "disorder, decentralization, and independent enactments of belief that spilled across boundaries of nation, empire, church, and period."56 In other words, the multiple transfers of the Santa Casa also involved the – increasingly global – circulation of new aspects of Catholicism. In the modern period, the most prominent analogous phenomenon has been the proliferation of Lourdes grottoes

near Augsburg and in Starý Hrozňatov near the Bohemian town of Cheb.55 Lauretan devotion spread to the Americas as well and was embraced by many indigenous people there, thanks not only to Jesuit propaganda but also to "disorder, decentralization, and independent enactments of belief that spilled across boundaries of nation, empire, church, and period."56 In other words, the multiple transfers of the Santa Casa also involved the – increasingly global – circulation of new aspects of Catholicism. In the modern period, the most prominent analogous phenomenon has been the proliferation of Lourdes grottoes .

.

The boundary between Western and Eastern Christianity was likewise permeable at the intersection of pilgrimage and iconographical replication. The story of Our Lady of Zhyrovichy illustrates this point. Zhyrovichy, a village in present-day Belarus, belonged to the early modern Grand Duchy of Lithuania and thus, after 1569, to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. An Orthodox monastery had existed here since the late 15th century. In the 1610s, its allegiance shifted to the Uniate Church, making Zhyrovichy a major Lithuanian center of Eastern Catholicism.57 Both Roman and Uniate Catholic pilgrims flocked there in great numbers to venerate the monastery's miracle-working Marian icon (see also below, section 6). What is more, via printed images produced by the Basilian Order in Vilnius, the iconography of Our Lady of Zhyrovichy traveled across the region and beyond, indeed all the way to Rome. There, at the Ruthenian Uniate 'national' church of Santi Sergio e Bacco, a copy of the icon was discovered in 1718 . Known as the Madonna del Pascolo, this replica quickly acquired a reputation for divine favors and turned the church into a pilgrimage site itself – attracting overwhelmingly local Catholics who adhered to Latin rather than Eastern Christianity.58 Extraordinary though it may be, the case of the Virgin of Zhyrovichy demonstrates that devotional transfer did not always proceed from 'the West' to 'the East' or from the Roman center into the supposed peripheries; things could go the other way around, too.

. Known as the Madonna del Pascolo, this replica quickly acquired a reputation for divine favors and turned the church into a pilgrimage site itself – attracting overwhelmingly local Catholics who adhered to Latin rather than Eastern Christianity.58 Extraordinary though it may be, the case of the Virgin of Zhyrovichy demonstrates that devotional transfer did not always proceed from 'the West' to 'the East' or from the Roman center into the supposed peripheries; things could go the other way around, too.

Shared Sacred Spaces: Transfer and Conflict

The study of cultural transfer risks yielding rose-tinted narratives of buoyant, peaceful exchange and "sharing is caring" unless we take conflicts and power imbalances into account. This caveat also applies to religious spaces – often pilgrimage sites – where people of different religious backgrounds interact. Such interreligious encounters were (and are) not always "antagonistic" and they do not necessarily turn violent in times of political crisis. Yet, contestation over holy places is common and vehement enough to merit close attention.59 After all, there is no dichotomy or zero-sum game between cultural transfer and cultural conflict; rather, the latter tends to be inextricably and uncomfortably intertwined with the former.

Although western European shrines such as Lourdes and Santiago de Compostela nowadays receive many non-Christian visitors, one must look primarily toward eastern Europe when studying post-medieval religious diversity and shared sacred spaces. Many of these spaces were situated in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during the early modern period. For instance, a kind of "syncretism" emerged at the small Muslim cemetery of Sinyavka, a minuscule town near Baranavichy in present-day Belarus. People who came to pray and ask for special divine favors at this cemetery included not only Muslim Tatars but also Christians and Jews, especially women.60 Perhaps less surprisingly, Catholics of different rites mingled at Zhyrovichy. In theory, political and ecclesiastical elites could hardly take issue with these encounters, since Roman and Uniate Catholics were supposed to get along well under the common spiritual leadership of the papacy. In practice, however, logistical and liturgical difficulties arose at the shrine because Latin-rite Catholics had adopted the Gregorian Calendar in the 1580s whereas Uniates continued to observe the older Julian Calendar. Against this backdrop, the Basilians petitioned the Roman Congregation de Propaganda Fide in 1684 to allow for the local introduction of the Gregorian Calendar at Zhyrovichy.61 This request seems to have never been granted – little wonder, given how frequently debates over the calendar inflamed inter-rite tensions in Poland-Lithuania.62 In other words, multi-rite pilgrimage to Zhyrovichy created a pull toward controversial cultural change: to what extent would the liturgical habits of Roman Catholic believers be accommodated and even prioritized at a Uniate shrine?

nowadays receive many non-Christian visitors, one must look primarily toward eastern Europe when studying post-medieval religious diversity and shared sacred spaces. Many of these spaces were situated in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during the early modern period. For instance, a kind of "syncretism" emerged at the small Muslim cemetery of Sinyavka, a minuscule town near Baranavichy in present-day Belarus. People who came to pray and ask for special divine favors at this cemetery included not only Muslim Tatars but also Christians and Jews, especially women.60 Perhaps less surprisingly, Catholics of different rites mingled at Zhyrovichy. In theory, political and ecclesiastical elites could hardly take issue with these encounters, since Roman and Uniate Catholics were supposed to get along well under the common spiritual leadership of the papacy. In practice, however, logistical and liturgical difficulties arose at the shrine because Latin-rite Catholics had adopted the Gregorian Calendar in the 1580s whereas Uniates continued to observe the older Julian Calendar. Against this backdrop, the Basilians petitioned the Roman Congregation de Propaganda Fide in 1684 to allow for the local introduction of the Gregorian Calendar at Zhyrovichy.61 This request seems to have never been granted – little wonder, given how frequently debates over the calendar inflamed inter-rite tensions in Poland-Lithuania.62 In other words, multi-rite pilgrimage to Zhyrovichy created a pull toward controversial cultural change: to what extent would the liturgical habits of Roman Catholic believers be accommodated and even prioritized at a Uniate shrine?

Throughout the early modern and modern periods, religiously diverse imaginaries and spaces of pilgrimage overlapped in southeastern Europe as well. Not far from Zagreb, for example, the church of Marija Bistrica developed into a major pilgrimage destination and, more specifically, into Croatia's "national" shrine between the late 17th and the 19th century. Even as political and ecclesiastical elites turned the Black Madonna venerated there into a symbol of the congruence between Croatian identity and Catholicity, some of the pilgrims who made their way to Marija Bistrica were actually Orthodox rather than Catholic.63 Similarly, in the multiconfessional contact zone of Transylvania, the Roman Catholic convent church of Maria Radna drew diverse crowds after becoming a key regional pilgrimage center in the early 1700s. When the bigger, Baroque church of Maria Radna was consecrated in June 1767 and more than 10,000 pilgrims attended the ceremonies, they listened to sermons "given in German, Hungarian, Illyrian, Croatian, Romanian, Bulgarian, [and] Armenian". Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, it seems that this shrine attracted Roman and Uniate Catholics as well as Orthodox Christians. Again, this did not mean that it was all sunshine and roses. Interchurch conflict simmered as Orthodox clergy suspected Maria Radna's Franciscan friars of pursuing an agenda of Catholicization sponsored by the Habsburg rulers, and rival Orthodox sites of pilgrimage kept popping up in this region.64

venerated there into a symbol of the congruence between Croatian identity and Catholicity, some of the pilgrims who made their way to Marija Bistrica were actually Orthodox rather than Catholic.63 Similarly, in the multiconfessional contact zone of Transylvania, the Roman Catholic convent church of Maria Radna drew diverse crowds after becoming a key regional pilgrimage center in the early 1700s. When the bigger, Baroque church of Maria Radna was consecrated in June 1767 and more than 10,000 pilgrims attended the ceremonies, they listened to sermons "given in German, Hungarian, Illyrian, Croatian, Romanian, Bulgarian, [and] Armenian". Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, it seems that this shrine attracted Roman and Uniate Catholics as well as Orthodox Christians. Again, this did not mean that it was all sunshine and roses. Interchurch conflict simmered as Orthodox clergy suspected Maria Radna's Franciscan friars of pursuing an agenda of Catholicization sponsored by the Habsburg rulers, and rival Orthodox sites of pilgrimage kept popping up in this region.64

Last but not least, pilgrimage from Europe to Jerusalem remained a high-stakes interfaith endeavor, even when the numbers of pious Christian travelers to Palestine dwindled in the early modern Ottoman period. Jerusalem's unique prestige was matched by the extraordinary diversity of religious groups that inhabited the city and laid claim to its holy sites. Struggles between the Franciscan pilgrimage custodians and local Orthodox clergy recurred in the early modern period.65 In the 19th century, the Russian Tsars sponsored – but also monitored – Orthodox pilgrimage to the Holy Land with increasing vigor, not least in order to advance their strategic interests vis-à-vis the struggling Ottoman Empire.66 Most remarkably, in the early modern era, Orthodox Southern Slavs living under Ottoman rule began to carry the honorific title of "hajji" after completing the pilgrimage to the Holy Land. This linguistic borrowing involved a shift in the pilgrims' understanding of their actions, a modelling of Christian pious travel on the Islamic hajj to Mecca, which illustrates how historical actors themselves could come to interpret pilgrimage as a cross-cultural practice.67

Conclusion

This entry has surveyed and analyzed the many roads taken by early modern and modern European pilgrims. Important historical differences exist between Europe's various pilgrimage traditions. For example, by the early modern period, Christianity had developed a highly polycentric network of shrines, no single one of which carried quite as much importance as did the holy city of Jerusalem for Jews and that of Mecca for Muslims. The rituals and meanings of pilgrimage varied widely as well. Yet, the trajectories of pilgrimage have often been thoroughly entangled with each other, whether one thinks of the Christian hajjis of southeastern Europe or the present-day mingling of spiritualities from all across the globe at Lourdes.

What is more, pilgrimage was an integral part of several macro-historical developments that rippled beyond religious boundaries and quickened the pace of cultural encounters. For one thing, the making of a triumphalist Baroque Catholicism relied heavily on the public mass spectacles of pilgrimage, especially to Marian shrines. This process presented great challenges to Protestantism and Orthodoxy in Europe, while also affecting the culture of indigenous societies in the Americas and other non-European parts of the world.68 In the 19th century, pilgrimage interacted – and often expanded – with new waves of imperial globalization, the industrial transport revolution of railroads and steamships, and the demise of serfdom in the Russian Empire. Considering the sheer strength of pilgrims' numbers along with the multiplicity of territorial and religious boundaries they crossed or navigated, pilgrimage ought to figure prominently in any transcultural history of Europe.

Kilian Harrer

Appendix

Sources

Archivio Storico de Propaganda Fide (APF), Rome, Congregazioni particolari 103: Ruteni 1748.

Balzamo, Nicolas et al. (eds.): L'"Atlas Marianus" de Wilhelm Gumppenberg: Édition et traduction, Neuchâtel 2015.

Chantre, Luc (ed.): Le pèlerinage à La Mecque, une affaire française: Anthologie de la langue française sur le hajj (1798–1963), Rennes 2021.

Hoernes, Moritz: Dinarische Wanderungen: Cultur- und Landschaftsbilder aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, Vienna 1888.

Jaucourt, Louis: Art. "Pèlerinage", in: Encyclopédie ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, etc. 12 (2017) [1751–1772], pp. 282–283. URL: https://artflsrv04.uchicago.edu/philologic4.7/encyclopedie0922/navigate/12/1048?byte=2900713 [2025-01-13]

Makulski, Franciszek: Bunty ukraińskie czyli Ukraińca nad Ukrainą uwagi z przydanym kazaniem w czasie klującego się buntu, in: Janusz Woliński et al. (eds.): Materiały do dziejów Sejmu Czteroletniego, Wrocław 1955–69, vol. 1, pp. 377–422.

Malinowski, Michael: Die Kirchen- und Staats-Satzungen bezüglich des griechisch-katholischen Ritus der Ruthenen in Galizien, Lviv 1861.

Marande, Félix: Les loisirs du pèlerinage: Itinéraire de Raon à Einsiedeln du 8 au 30 août 1832, Basel 2007.

Velykyj, Atanasij H. (ed.): Supplicationes Ecclesiae Unitae Ucrainae et Bielarusjae, Rome 1960–65.

Literature

Albareda, Anselm M. / Massot i Muntaner, Josep: Historia de Montserrat, Montserrat 1974.

Amer Meziane, Mohamad: Des empires sous la terre: Histoire écologique et raciale de la sécularisation, Paris 2021.

Antoniewicz, Marceli et al. (eds.): Częstochowa: Dzieje miasta i klasztoru jasnogórskiego, Częstochowa 2002–2007 (Monografia historyczna Częstochowy).

Armstrong, Megan C.: The Holy Land and the Early Modern Reinvention of Catholicism, New York 2021. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108957946 [2025-01-13]

Balzamo, Nicolas: L'infrastructure de l'Atlas Marianus: Les livrets de pèlerinage à l'époque moderne (XVIe–XVIIe siècles), in: Olivier Christin et al. (eds.): Marie mondialisée: L'Atlas Marianus de Wilhelm Gumppenberg et les topographies sacrées de l'époque moderne, Neuchâtel 2014 (Image et patrimoine, pp. 121–130.

Balzamo, Nicolas: Religion populaire, in: Olivier Christin et al. (eds.): Dictionnaire des concepts nomades en sciences humaines, Paris 2016, pp. 257–271.

Berbée, Paul: Zur Klärung von Sprache und Sache in der Wallfahrtsforschung: Begriffsgeschichtlicher Beitrag und Diskussion, in: Bayerische Blätter für Volkskunde 14 (1987), pp. 65–82.

Bercé, Yves-Marie: Lorette aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles: Histoire du plus grand pèlerinage des temps modernes, Paris 2011 (Collection du Centre Roland Mousnier).

Bidmon, Elfriede (ed.): Eine kleine Wallfahrt durch 350 Jahre: Maria Loreto Gnadenstätte im Egerland, Altkinsberg-Hrozňatov, 7th ed., Nürnberg 2013.

Bilska-Wodecka, Elżbieta: Kalwarie europejskie: Analiza struktury, typów i genezy, Kraków 2003.

Blackbourn, David: Marpingen: Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Nineteenth-Century Germany, New York 1994. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198217831.001.0001 [2025-01-13]

Blaschke, Olaf: Abschied von der Säkularisierungslegende: Daten zur Karrierekurve der Religion (1800-1970) im zweiten konfessionellen Zeitalter: eine Parabel, in: zeitenblicke 5 (2006). URL: https://www.zeitenblicke.de/2006/1/Blaschke [2025-01-13]

Bouflet, Joachim / Boutry, Philippe: Un signe dans le ciel: Les apparitions de la Vierge, Paris 1997.

Boutry, Philippe et al. (eds.): Reine au Mont Auxois: Le culte et le pèlerinage de sainte Reine des origines à nos jours, Dijon 1997.

Boutry, Philippe / Le Hénand, Françoise: Pèlerins parisiens à l'âge de la monarchie administrative, in: Philippe Boutry et al. (eds.): Rendre ses vœux: Les identités pèlerines dans l'Europe moderne (XVIe–XVIIIe siècle), Paris 2000 (Civilisations et sociétés 100), pp. 401–437.

Bowman, Glenn (ed.): Sharing the Sacra: The Politics and Pragmatics of Intercommunal Relations around Holy Places, New York 2012. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qctg2 [2025-01-13]

Breger, Marshall J. / Hammer, Leonard M.: The Contest and Control of Jerusalem's Holy Sites: A Historical Guide to Legality, Status, and Ownership, Cambridge 2023. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108886420 [2025-01-13]

Bringa, Tone / Henig, David: Seeking Blessing and Earning Merit: Muslim Travellers in Bosnia-Hercegovina, in: Ingvild Flaskerud et al. (eds.): Muslim Pilgrimage in Europe, London et al. 2018 (Routledge Studies in Pilgrimage, Religious Travel and Tourism), pp. 83–97. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315597089 [2025-01-13]

Brown, Peter: The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity, Chicago 1981 (Haskell lectures on history of religions new ser., no. 2). URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb01044.0001.001 [2025-01-13]

Brückner, Wolfgang: Die Verehrung des Heiligen Blutes in Walldürn: Volkskundlich-soziologische Untersuchungen zum Strukturwandel barocken Wallfahrtens, Aschaffenburg 1958.

Brugger, Eva: Gedruckte Gnade: Die Dynamisierung der Wallfahrt in Bayern (1650‒1800), Affalterbach 2017.

Burkardt, Albrecht (ed.): L'économie des dévotions: Commerce, croyances et objets de piété à l'époque moderne, Rennes 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.45338 [2025-01-13]

Can, Lâle: Spiritual Subjects: Central Asian Pilgrims and the Ottoman Hajj at the End of Empire, Stanford 2020. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503611177 [2025-01-13]

Christian, William A.: Local Religion in Sixteenth-Century Spain, Princeton 1981. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691241906 [2025-01-137]

Cohen-Hattab, Kobi: Zionist Pilgrimages: The Beginning of Organized Zionist Jewish Tourism to Palestine at the End of the Ottoman Period, in: Jewish Culture and History 23 (2022), pp. 201–220. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/1462169X.2022.2084219 [2025-01-13]

Dabrowski, Patrice M.: Multiple Visions, Multiple Viewpoints: Apparitions in a German–Polish Borderland, 1877–1880, in: The Polish Review 58 (2013), pp. 35–64. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/polishreview.58.3.0035 [2025-01-13]

Davis, Natalie Zemon: From "Popular Religion" to Religious Cultures, in: Steven E. Ozment (ed.): Reformation Europe: A Guide to Research, St. Louis 1982, pp. 321–341.

Delfosse, Annick: Pèlerinages à la Vierge, pèlerinages de genre? Le cas des Pays-Bas catholiques et de la Principauté de Liège au XVIIe siècle: tâtonnements et impasses, in: Juliette Dor et al. (eds.): Femmes et pèlerinages: Women and pilgrimages, Santiago de Compostela 2007 (The way to Santiago 2), pp. 75–93. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2268/2470 [2025-01-13]

Dipper, Christof: Volksreligiosität und Obrigkeit im 18. Jahrhundert, in: Wolfgang Schieder (ed.): Volksreligiosität in der modernen Sozialgeschichte, Göttingen 1986 (Geschichte und Gesellschaft Sonderheft 11), pp. 73–96. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40194753 [2025-01-13]

Ditchfield, Simon: Liturgy, Sanctity and History in Tridentine Italy: Pietro Maria Campi and the Preservation of the Particular, Cambridge 1995.

Dohms, Peter (ed.): Kleine Geschichte der Kevelaer-Wallfahrt, Kevelaer 2008.

Doney, Skye: The Persistence of the Sacred: German Catholic Pilgrimage, 1832–1937, Toronto 2022. URL: https://doi.org/10.3138/9781487543129 [2025-01-13]

Duhamelle, Christophe: Les pèlerins de passage à l'hospice zum Heiligen Kreuz de Nuremberg au XVIIIe siècle, in: Philippe Boutry et al. (eds.): Rendre ses vœux: Les identités pèlerines dans l'Europe moderne (XVIe–XVIIIe siècle), Paris 2000 (Civilisations et sociétés 100), pp. 39–56.

Duhamelle, Christophe: La frontière au village: Une identité catholique allemande au temps des Lumières, Paris 2010.

Dünninger, Hans: Was ist Wallfahrt? Erneute Aufforderung zur Diskussion um eine Begriffsbestimmung [1963], in: Wolfgang Brückner et al. (eds.): Wallfahrt und Bilderkult: Gesammelte Schriften, Würzburg 1995, pp. 271–281.

Dupront, Alphonse: Du Sacré: Croisades et pèlerinages, images et langages, Paris 1987 (Bibliothèque des histoires).

Dyas, Dee: The Dynamics of Pilgrimage: Christianity, Holy Places, and Sensory Experience, New York et al. 2021 (Routledge Studies in Pilgrimage, Religious Travel and Tourism). URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003094968 [2025-01-13]

Eade, John et al. (eds.): Contesting the Sacred: The Anthropology of Christian Pilgrimage, Urbana 2000 [1991]. URL: urn:oclc:record:1357504878 [2025-01-13]

Emich, Birgit: Uniformity and Polycentricity: The Early Modern Papacy between Promoting Unity and Handling Diversity, in: Birgit Emich et al. (eds.): Pathways through Early Modern Christianities, Cologne 2023 (Kulturen des Christentums / Cultures of Christianity 1), pp. 33–53. URL: https://doi.org/10.7788/9783412526085.33 [2025-01-13]

Fässler, Thomas: Aufbruch und Widerstand: Das Kloster Einsiedeln im Spannungsfeld von Barock, Aufklärung und Revolution, Egg bei Einsiedeln 2019.

Fennell, Nicholas: The Russians on Athos, Oxford 2001.

Forster, Marc R.: Catholic Revival in the Age of the Baroque: Religious Identity in Southwest Germany, 1550–1750, New York 2001 (New studies in European history).

Freitag, Werner: Volks- und Elitenfrömmigkeit in der frühen Neuzeit: Marienwallfahrten im Fürstbistum Münster, Paderborn 1991 (Veröffentlichungen des Provinzialinstituts für Westfälische Landes- und Volksforschung des Landschaftsverbandes Westfalen-Lippe 29).

García Fernández: Máximo, Religiosidad popular y comportamientos colectivos: Europa, siglo XVI-1830, in: Cristianesimo nella Storia 38 (2017), pp. 495–516.

Gentile, Guido: Sacri Monti, Torino 2019 (Saggi 986).

Gitlitz, David M. / Davidson, Linda Kay: Pilgrimage and the Jews, Westport 2006.

Gothóni, René: Tales and Truth: Pilgrimage on Mount Athos: Past and Present, Helsinki 1994.

Grimaldi, Floriano: Pellegrini e pellegrinaggi a Loreto nei secoli XIV–XVIII, Loreto 2001.

Guth, Klaus: Geschichtlicher Abriss der marianischen Wallfahrtsbewegungen im deutschsprachigen Raum, in: Wolfgang Beinert et al. (eds.): Handbuch der Marienkunde, Regensburg 1997 [1984], vol. 2, pp. 321–448.

Harrer, Kilian: Erlaubte und unerlaubte Wallfahrt: Neue Erkenntnisse zum Andrang bei der Trierer Heilig-Rock-Zeigung von 1810, in: Archiv für mittelrheinische Kirchengeschichte 75 (2023), pp. 199–219.

Harrer, Kilian: Mass Pilgrimage and the Usable Empire in a Napoleonic Borderland, in: The Historical Journal 66 (2023), pp. 773–794. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X23000080 [2025-01-13]

Harris, Ruth: Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age, New York et al. 1999.

Hayden, Robert M.: Antagonistic Tolerance: Competitive Sharing of Religious Sites in South Asia and the Balkans, in: Current Anthropology 43,2 (2002), pp. 205–231. URL: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/338303 [2025-01-13]

Hersche, Peter: Muße und Verschwendung: Europäische Gesellschaft und Kultur im Barockzeitalter, Freiburg et al. 2006.

Holzem, Andreas: Piété, culture populaire, monde vécu: Conceptualiser la pratique religieuse chrétienne, in: Philippe Büttgen et al. (eds.): Religion ou confession? Un bilan franco-allemand sur l'époque moderne (XVIe–XVIIIe siècles), Paris 2010, pp. 121–150.

Hrovatin, Mirela: The Mother of God of Bistrica Shrine as Croatian National Pilgrimage Center, in: Dorina Dragnea et al. (eds.): Pilgrimage in the Christian Balkan World: The Path to Touch the Sacred and Holy, Turnhout 2023, pp. 165–183. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1484/M.STR-EB.5.131895 [2025-01-13]

Huber, Valeska: Channelling Mobilities: Migration and Globalisation in the Suez Canal Region and beyond, 1869–1914, Cambridge 2013. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139344159 [2025-01-13]

Iseli, Andrea: Gute Policey: Öffentliche Ordnung in der frühen Neuzeit, Stuttgart 2009 (UTB 3271). URL: https://elibrary.utb.de/doi/book/10.36198/9783838532714 [2025-01-13]

Izmirlieva, Valentina: Christian Hajjis – the Other Orthodox Pilgrims to Jerusalem, in: Slavic Review 73 (2014), pp. 322–346. URL: https://doi.org/10.5612/slavicreview.73.2.322 [2025-01-13]

Julia, Dominique: Pour une géographie européenne du pèlerinage à l'époque moderne et contemporaine, in: Philippe Boutry et al. (eds.): Pèlerins et pèlerinages dans l'Europe moderne, Rome 2000, pp. 3–126.

Julia, Dominique: Le voyage aux saints: Les pèlerinages dans lʼOccident moderne, XVe–XVIIIe siècle, Paris 2016.

Kälin, Kari: Schauplatz katholischer Frömmigkeit: Wallfahrt nach Einsiedeln von 1864 bis 1914, Fribourg 2005 (Religion – Politik – Gesellschaft in der Schweiz 38).

Kane, Eileen M.: Pilgrims, Holy Places, and the Multi-Confessional Empire: Russian Policy toward the Ottoman Empire under Tsar Nicholas I: 1825–1855, Ph.D. diss., Princeton 2005.

Kane, Eileen M.: Russian Hajj: Empire and the Pilgrimage to Mecca, Ithaca 2015. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt20d88tf [2025-01-13]

Kaufman, Suzanne K.: Consuming Visions: Mass Culture and the Lourdes Shrine, Ithaca 2005. URL: https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501727351 [2025-01-13]

Kenworthy, Scott M.: The Heart of Russia: Trinity-Sergius, Monasticism, and Society after 1825, Washington 2010.

Kizlova, Antonina: Usamitnennja v natovpi: socialʹni vzajemodiï bratiï pry šanovnych svjatynjach Kyjevo-Pečersʹkoï Uspensʹkoï lavry (1786–perši desjatylittja XX st.) (= Seclusion in the crowd: social interactions of brethren related to sacred objects of Kyiv Dormition Caves Lavra (1786–the 1st decades of the 20th cent.), Kyïv 2019.

Kuehn, Sara: Pilgrimage as Muslim Religious Commemoration: The Case of Ajvatovica in Bosnia-Hercegovina, in: Ingvild Flaskerud et al. (eds.): Muslim Pilgrimage in Europe, London et al. 2018 (Routledge Studies in Pilgrimage, Religious Travel and Tourism), pp. 98–117.

La Coste-Messelière: René de, Édits et autres actes royaux contre les abus des pèlerinages à l'étranger aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles et la pérennité du pèlerinage à Saint-Jacques de Compostelle, in: Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques (ed.): Actes du quatre-vingt-quatorzième congrès national des sociétés savantes. Pau, 1969: Section d'histoire moderne et contemporaine, Tome I, Les relations franco-hispaniques, Paris 1971, pp. 115–128.

Landi, Sandro: Législations sur les pèlerinages et identités pèlerines dans la péninsule italienne, XVIe–XVIIIe siècle, in: Philippe Boutry et al. (eds.): Rendre ses vœux: Les identités pèlerines dans l'Europe moderne (XVIe–XVIIIe siècle), Paris 2000 (Civilisations et sociétés 100), pp. 457–471.

Laurentin, René et al. (eds.): Dictionnaire des "apparitions" de la Vierge Marie: Inventaire des origines à nos jours, méthodologie, bilan interdisciplinaire, prospective, Paris 2007.

Lobenwein, Elisabeth: Wallfahrt – Wunder – Wirtschaft: Die Wallfahrt nach Maria Luggau (Kärnten) in der Frühen Neuzeit, Bochum 2013.

Lotz-Heumann, Ute: Repräsentationen von Heilwassern und -quellen in der Frühen Neuzeit: Badeorte, lutherische Wunderquellen und katholische Wallfahrtsorte, in: Matthias Pohlig et al. (eds.): Säkularisierungen in der Frühen Neuzeit: Methodische Probleme und empirische Fallstudien, Berlin 2008 (Zeitschrift für historische Forschung Beiheft 41), pp. 277–330. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1q6b1nt [2025-01-137]

Lyons, John D. (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Baroque, New York 2019 (Oxford handbooks). URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190678449.001.0001 [2025-01-13]

Maes, Bruno: Le roi, la Vierge et la nation: Pèlerinages et identité nationale entre guerre de Cent Ans et Révolution, Paris 2003 (La France au fil des siècles).

Maes, Bruno: Notre-Dame de Liesse: Une vierge noire en Picardie, Langres 2009 (Sanctuaires et pèlerinages).

Maes, Bruno: Les livrets de pèlerinage: Imprimerie et culture dans la France moderne, Rennes 2016 (Histoire).

Martin, Philippe: Les chemins du sacré: Paroisses, processions, pèlerinages en Lorraine, du XVIe au XIXe siècle, Metz 1995.

Martin, Philippe: Sanctuaires-mères et pèlerinages-relais, in: Catherine Vincent (ed.): Identités pèlerines: Actes du colloque de Rouen, 15–16 mai 2002, Rouen 2004, pp. 107–122.

Mínguez Blasco, Raúl: ¿Dios cambió de sexo?: El debate internacional sobre la feminización de la religión y algunas reflexiones para la España decimonónica, in: Historia contemporánea 51 (2015), pp. 397–426.

Mironowicz, Antoni: Z dziejów żyrowickiego sanktuarium: Lata 1470–1618, Białystok 2021.

Molitor, Hansgeorg et al. (eds.): Volksfrömmigkeit in der frühen Neuzeit, Münster 1994.

Mróz, Franciszek: Geneza i typologia sanktuariów Pańskich w Polsce, Kraków 2021 (Prace Monograficzne / Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny im. Komisji Edukacji Narodowej w Krakowie 1016).

Nicault, Catherine: Les pèlerinages français en Terre Sainte au XIXe siècle, in: Daniel Tollet (ed.): Études sur les terres saintes et les pèlerinages dans les religions monothéistes, Paris 2012 (Bibliothèque des religions du monde 1), pp. 163–176.

Nicklas, Thomas: Einleitung: Glaubensformen zwischen Volk und Eliten, in: Thomas Nicklas (ed.): Glaubensformen zwischen Volk und Eliten: Frühneuzeitliche Praktiken und Diskurse zwischen Frankreich und dem Heiligen Römischen Reich, Halle 2012, pp. 9–19.

Niedźwiedź, Anna: Obraz i postać: Znaczenia wizerunku Matki Boskiej Częstochowskiej, Kraków 2005.

Niendorf, Mathias: Das Großfürstentum Litauen: Studien zur Nationsbildung in der Frühen Neuzeit (1569–1795), Wiesbaden 2006 (Veröffentlichungen des Nordost-Instituts 3).

Oechslin, Werner (ed.): Die Vorarlberger Barockbaumeister: Ausstellung in Einsiedeln und Bregenz zum 250. Todestag von Br. Caspar Moosbrugger, Mai bis September 1973, Einsiedeln 1973.

Osterhammel, Jürgen: Die Verwandlung der Welt: Eine Geschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts, München 2013 [2009].

Ostrowski, Jan K.: Forgotten Baroque Borderland, in: Joanna Wasilewska-Dobkowska (ed.): Poland – China: Art and Cultural Heritage, Kraków 2011, pp. 63–72. URL: https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00006962 [2025-01-13]

Pack, Sasha D.: Revival of the Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela: The Politics of Religious, National, and European Patrimony, 1879–1988, in: Journal of Modern History 82 (2010), pp. 335–367. URL: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/651613 [2025-01-13]

Pantea, Maria Alexandra: Pilgrimages and Pilgrims in the Arad County as an Expression of the Confessional, Ethnic and Socio-political Realities (1700–1939), in: Dorina Dragnea et al. (eds.): Pilgrimage in the Christian Balkan World: The Path to Touch the Sacred and Holy, Turnhout 2023, pp. 145–163. URL: https://doi.org/10.1484/M.STR-EB.5.132404 [2025-01-13]

Peyrard, Christine: De la liberté cultuelle à la police des cultes: La première Séparation des Églises et de l'État en France, in: Christine Peyrard (ed.): Politique, religion et laïcité, Aix-en-Provence 2009, pp. 89–100. URL: https://directory.doabooks.org/handle/20.500.12854/56597 [2025-01-13]

Picard, Michel-Jean: Croix (Chemin de), in: Marcel Viller (ed.): Dictionnaire de spiritualité ascétique et mystique: Doctrine et histoire, Paris 1953, vol. 2, cols. 2576–2606. URL: https://archive.org/details/dictionnaire-de-spiritualite-tome-04.2-esp-ez/Dictionnaire%20de%20Spiritualit%C3%A9%20tome%2002.2%20%28Com-Cy%29/page/n659/mode/2up [2025-01-13]

Pötzl, Walter: Loreto-Madonna und Heiliges Haus: Die Wallfahrt auf dem Kobel: Ein Beitrag zur europäischen Kult- und Kulturgeschichte, Augsburg 2000.

Price, Roger: Religious Renewal in France, 1789–1870: The Roman Catholic Church between Catastrophe and Triumph, New York 2018.

Reader, Ian: Pilgrimage Growth in the Modern World: Meanings and Implications, in: Religion 37 (2007), pp. 210–229.

Reinhardt, Rudolf: Die Kritik der Aufklärung am Wallfahrtswesen, in: Bausteine zur geschichtlichen Landeskunde von Baden-Württemberg: Herausgegeben von der Kommission für geschichtliche Landeskunde in Baden-Württemberg anläßlich ihres 25jährigen Bestehens, Stuttgart 1979, pp. 319–345.

Reiter, Günther: Heiligenverehrung und Wallfahrtswesen im Schrifttum von Reformation und katholischer Restauration, Würzburg 1970.

Reiter, Yitzhak: Contested Holy Places in Israel-Palestine: Sharing and Conflict Resolution, Abingdon 2017. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315277271 [2025-01-13]

Ridehalgh, Anna: Preromantic Attitudes and the Birth of a Legend: French Pilgrimages to Ermenonville, 1778–1789, in: Haydn Trevor Mason (ed.): Miscellany/Mélanges, Oxford 1982 (Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 215), pp. 231–252.

Ringholz, Odilo: Wallfahrtsgeschichte Unserer Lieben Frau von Einsiedeln: Ein Beitrag zur Culturgeschichte, Freiburg im Breisgau 1896.

Robson, Roy R.: Solovki: The Story of Russia Told Through Its Most Remarkable Islands, New Haven et al. 2004.

Ryad, Umar (ed.): The Hajj and Europe in the Age of Empire, Leiden et al. 2017 (Leiden studies in Islam and society 5). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h34p [2025-01-13]

Sallmann, Jean-Michel: Naples et ses saints à l'âge baroque: 1540–1750, Paris 1994.

Sayeed, Asma: Women and the Hajj, in: Eric Tagliacozzo et al. (eds.): The Hajj: Pilgrimage in Islam, Cambridge 2015, pp. 65–84. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139343794.006 [2025-01-137]

Schieder, Wolfgang: Kirche und Revolution: Sozialgeschichtliche Aspekte der Trierer Wallfahrt von 1844, in: Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 14 (1974), pp. 419–454.

Schieder, Wolfgang (ed.): Volksreligiosität in der modernen Sozialgeschichte, Göttingen 1986 (Geschichte und Gesellschaft Sonderheft 11). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40006248 [2025-01-13]

Schneider, Bernhard: Wallfahrt und Kommunikation – Kommunikation über Wallfahrt: Einleitende Bemerkungen zu einem Forschungsfeld, in: Bernhard Schneider (ed.): Wallfahrt und Kommunikation, Kommunikation über Wallfahrt, Mainz 2004 (Quellen und Abhandlungen zur mittelrheinischen Kirchengeschichte 109), pp. 6–16.

Schneider, Bernhard: Wallfahrtskritik im Spätmittelalter und in der 'Katholischen Aufklärung': Beobachtungen zu Kontinuität und Wandel, in: Bernhard Schneider (ed.): Wallfahrt und Kommunikation, Kommunikation über Wallfahrt, Mainz 2004 (Quellen und Abhandlungen zur mittelrheinischen Kirchengeschichte 109), pp. 281–316.

Sidler, Daniel: Heiligkeit aushandeln: Katholische Reform und lokale Glaubenspraxis in der Eidgenossenschaft (1560–1790), Frankfurt am Main 2017.

Sinkevych, Nataliia: The Religiosæ Kijovienses Cryptæ by Johannes Herbinius (1675): A Description of Kyiv and Its "Sacral Space" in Early Modern Multiconfessional Discourse, Lviv 2022 (Kyivan christianity 29).

Slight, John: The British Empire and the Hajj: 1865–1956, Cambridge, Mass. 2015. URL: https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674495029 [2025-01-13]

Speth, Volker: Katholische Aufklärung, Volksfrömmigkeit und 'Religionspolicey': Das rheinische Wallfahrtswesen von 1814 bis 1826 und die Entstehungsgeschichte des Wallfahrtsverbots von 1826: Ein Beitrag zur aufklärerischen Volksfrömmigkeitsreform, 2nd ed., Frankfurt am Main 2014 [2008].

Stannek, Antje: Les pèlerins allemands à Rome et à Lorette à la fin du XVIIe et au XVIIIe siècle, in: Philippe Boutry et al. (eds.): Pèlerins et pèlerinages dans l'Europe moderne, Rome 2000, pp. 327–354.

Stavrou, Theofanis G.: Russian Interests in Palestine 1884–1914: A Study of Religious and Educational Enterprise, Thessaloniki 1963.

Stradomski, Jan: O merytorycznych i konfesyjnych problemach reformy kalendarza w świetle XVI- i XVII-wiecznej polemiki religijnej w Rzeczypospolitej, in: Piotr Chomik (ed.): "Pokazanie cerkwie prawdziwej…": Studia nad dziejami i kulturą Kościoła prawosławnego w Rzeczypospolitej, Białystok 2004, pp. 37–72.

Sumption, Jonathan: The Age of Pilgrimage: The Medieval Journey to God, Mahwah 2003 [1975]. URL: urn:oclc:record:1024172670 [2025-01-13]

Tatarenko, Laurent: I Ruteni a Roma: I monaci basiliani della chiesa dei Santi Sergio e Bacco (secoli XVII–XVIII), in: Antal Molnár et al. (eds.): Chiese e nationes a Roma: Dalla Scandinavia ai Balcani, secoli XV–XVIII, Rome 2017 (Bibliotheca Academiae Hungariae Roma, Studia 6), pp. 175–191.

Taylor, William B.: Theater of a Thousand Wonders: A History of Miraculous Images and Shrines in New Spain, New York 2016 (Cambridge Latin American studies 103). URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316212615 [2025-01-13]

Thurston, Herbert: The Stations of the Cross: An Account of their History and Devotional Purpose, London 1906. URL: urn:oclc:record:1085316270 [2025-01-13]

Tingle, Elizabeth C.: Sacred Journeys in the Counter-Reformation: Long-Distance Pilgrimage in Northwest Europe, Boston et al. 2020 (Research in Medieval and Early Modern Culture 27). URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501514388 [2025-01-13]

Torpey, John C.: The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State, Cambridge 2000. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511520990 [2025-01-13]

Upart, Anatole: Madonna del Pascolo: Ruthenian Heritage in Baroque Rome and the Development of the National Church of Ukrainians, in: Dragan Damjanović et al. (eds.): Forging Architectural Tradition: National Narratives, Monument Preservation and Architectural Work in the Nineteenth Century, New York et al. 2022 (Explorations in Heritage Studies 4), pp. 314–334. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.2711505.17 [2025-01-13]

Vélez, Karin: The Miraculous Flying House of Loreto: Spreading Catholicism in the Early Modern World, Princeton 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv301ggq [2025-01-13]

Vismara, Paola: Santuari e pellegrinaggi: Un problema pastorale?, in: Andrea Tilatti (ed.): Santuari di confine: Una tipologia? Atti del convegno di studi, Gorizia, Nova Gorica, 7–8 ottobre 2004, Gorizia 2008, pp. 21–37.

Walsham, Alexandra: The Reformation of the Landscape: Religion, Identity, and Memory in Early Modern Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2011. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199243556.001.0001 [2025-01-13]

Wereda, Dorota: Biskupi uniccy wobec reform kalendarza w drugiej połowie XVIII wieku, in: Roczniki Humanistyczne 59,2 (2011), pp. 147–169. URL: https://ojs.tnkul.pl/index.php/rh/article/view/5732 [2025-01-13]

Woeckel, Gerhard P.: Pietas Bavarica: Wallfahrt, Prozession und Ex-voto-Gabe im Hause Wittelsbach in Ettal, Wessobrunn, Altötting und der Landeshauptstadt München von der Gegenreformation bis zur Säkularisation und der "Renovatio Ecclesiae", Weissenhorn 1992.

Worobec, Christine D.: The Unintended Consequences of a Surge in Orthodox Pilgrimages in Late Imperial Russia, in: Russian History 36 (2009), pp. 62–76. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24664585 [2025-01-13]

Worobec, Christine D.: Commentary: The Coming of Age of Eastern Orthodox Pilgrimage Studies, in: Modern Greek Studies Yearbook 28/29 (2012/2013), pp. 219–236.

Worobec, Christine D.: The Long Road to Kiev: Nineteenth-Century Orthodox Pilgrimages, in: Modern Greek Studies Yearbook 30/31 (2014/2015), pp. 1–22.

Wyczawski, Hieronim Eugeniusz: Kalwaria Zebrzydowska: Historia klasztoru Bernardynów i kalwaryjskich dróżek, 2nd ed., Kalwaria Zebrzydowska 2006.

Zimdars-Swartz, Sandra: Encountering Mary: From La Salette to Medjugorje, Princeton 1991. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400861637 [2025-01-13]

Žitenëv, Sergej Jurʹevič: Istorija russkogo pravoslavnogo palomničestva v X–XVII vekach, Moscow 2007.

Zuckerman, Maja Gildin: Pilgrimage Zionism: The Maccabean Pilgrimage to Palestine and the Divergent Processes of Zionist Meaning Making, in: Jewish Culture and History 22 (2021), pp. 189–208. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/1462169X.2021.1956791 [2025-01-13]

Notes

- ^ In addition, different forms of ostensibly secular mobility have often been understood as pilgrimages, e.g., late-18th-century French people visiting the tomb of Rousseau in Ermenonville, or U.S. war veterans going on motorcycle rides to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C.; see, e.g., Ridehalgh, Preromantic Attitudes 1982; Reader, Pilgrimage Growth 2007, p. 213. This entry, however, focuses on pilgrimage as practiced within the Abrahamic religious traditions.

- ^ Indeed, the distinction between "pilgrimage" and "procession" became blurred when, as was common in Catholic Europe at least until the mid-20th century, a rural community would pay collective homage to a saint by visiting a small shrine in a neighboring village. On the terminological and phenomenological problems raised by these short trips, see the folklorist debate sparked by Dünninger, Was ist Wallfahrt? 1995, and aptly summarized by Berbée, Zur Klärung 1987.

- ^ Sumption, The Age of Pilgrimage 2003 [1975].

- ^ Lutheran and Reformed church authorities strenuously condemned pilgrimage and associated practices such as the cult of saints, the veneration of relics, and ascetic exercises. Luther, Calvin, and other Protestant theologians rejected pilgrimage for various reasons, most importantly the new doctrines of justification. If, as Luther argued, a person's justification could only be secured by faith alone (sola fide), then "good works" such as pilgrimage could not earn merit at a soteriological level, i.e., with regard to salvation. Nor did it make any sense to invoke the saints as mediators of either salvation or God’s grace. See Reiter, Heiligenverehrung und Wallfahrtswesen 1970, pp. 18–31. In the long run, these combats against pilgrimage proved largely successful, even though some recoded forms of spiritual travel, such as trips to certain holy wells, remained socially acceptable among early modern Protestants: Walsham, The Reformation of the Landscape 2011, ch. 6; Lotz-Heumann, Repräsentationen von Heilwassern 2008. Their 19th-century successors would, moreover, develop a new fascination with the Holy Land: Dyas, The Dynamics of Pilgrimage 2021, pp. 258–264.

- ^ Hersche, Muße und Verschwendung 2006; Lyons, The Oxford Handbook 2019. Two exemplary monographs: Forster, Catholic Revival 2001; Sallmann, Naples et ses saints 1994.

- ^ Julia, Pour une géographie 2000; Tingle, Sacred Journeys 2020; La Coste-Messelière, Édits et autres actes royaux 1971; Pack, Revival 2010.

- ^ Julia, Pour une géographie 2000, pp. 45f.

- ^ Doney, The Persistence 2022; Harrer, Erlaubte und unerlaubte Wallfahrt 2023; Blaschke, Abschied 2006.

- ^ On Loreto: Bercé, Lorette 2011; Grimaldi, Pellegrini e pellegrinaggi 2001. On Montserrat: Albareda, Massot i Muntaner, Historia de Montserrat 1974. On Liesse: Maes, Notre-Dame de Liesse 2009. On Einsiedeln: Fässler, Aufbruch und Widerstand 2019; Ringholz, Wallfahrtsgeschichte 1896. On Kevelaer: Dohms, Kleine Geschichte 2008. On Walldürn: Brückner, Die Verehrung 1958. On Altötting and Mariazell, see, e.g., Guth, Geschichtlicher Abriss 1997 [1984], esp. pp. 816–818. On Jasna Góra: Niedźwiedź, Obraz i postać 2005; Antoniewicz, Częstochowa 2002–2007.

- ^ See above all Harris, Lourdes 1999. The literature on modern Marian apparitions is vast; for helpful overviews and compelling case studies, see Zimdars-Swartz, Encountering Mary 1991; Bouflet / Boutry, Un signe dans le ciel 1997; Laurentin, Dictionnaire des "apparitions" 2007; Blackbourn, Marpingen 1994; Dabrowski, Multiple Visions 2013.

- ^ While pilgrimage to these smaller shrines is a less salient topic when it comes to the history of (inter)cultural transfers, pilgrim mobility cannot be adequately understood without taking into account these smaller sites. Many smaller shrines formed symbiotic relationships with larger ones, serving in some ways as spatial relays of the sacred: Martin, Sanctuaires-mères 2004; see also section 5 of this entry. Shrines of local or regional importance were in most cases visited by a few thousand pilgrims each year but in some instances by more than 50,000. What is more, by the later 18th century, as many as several thousands of churches and chapels may have functioned as pilgrimage destinations in the southern half of German-speaking Europe alone: Hersche, Muße und Verschwendung 2006, pp. 800f. (Other Catholic regions may not quite have matched this density of shrines.)

- ^ Gothóni, Tales and Truth 1994, p. 178; see also Fennell, The Russians on Athos 2001.

- ^ Worobec, The Unintended Consequences 2009; Worobec, The Long Road 2014/2015.

- ^ Sinkevych, The Religiosæ Kijovienses Cryptæ 2022; Malinowski, Die Kirchen- und Staats-Satzungen 1861, pp. 71 and 78; Makulski, Bunty ukraińskie 1955–69, pp. 392f.; APF, CP 103, fols. 417f., letter from Mikołaj Dembowski (c. 1680–1757, Roman Catholic bishop of Kamianets-Podilskyi) to the papal curia, 28 November 1756, here fol. 418r: "Chioviam ad scismaticas Eccl[esi]as visitandas, sexaginta, octuaginta milliaria polonica, et ultra usque centum unitorum millia annuatim peragi affirmatur”.

- ^ Kenworthy, The Heart of Russia 2010; Robson, Solovki 2004; for earlier periods, see Žitenëv, Istorija russkogo pravoslavnogo palomničestva 2007.

- ^ By comparison, only 14 million Muslims lived in the late Ottoman Empire. Kane, Russian Hajj 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Osterhammel, Die Verwandlung 2013 [2009], p. 249. On the hajj and European imperialism, see also Chantre, Le pèlerinage 2021; Ryad, The Hajj and Europe 2017; Kane, Russian Hajj 2015; Slight, The British Empire 2015.

- ^ Kuehn, Pilgrimage as Muslim Religious Commemoration 2018; Bringa / Henig, Seeking Blessing 2018; see also Hoernes, Dinarische Wanderungen 1888, pp. 279f.

- ^ Zuckerman, Pilgrimage Zionism 2021; Cohen-Hattab, Zionist Pilgrimages 2022.

- ^ Gitlitz / Davidson, Pilgrimage and the Jews 2006, pp. 103–122 (see also Gitlitz / Davidson, Pilgrimage and the Jews 2006, pp. 125f., on pilgrimage customs of Sephardic Jews on the Balkans).

- ^ Schieder, Volksreligiosität 1986; Dupront, Du Sacré 1987, pp. 419–466; Freitag, Volks- und Elitenfrömmigkeit 1991; Molitor, Volksfrömmigkeit 1994; Nicklas, Einleitung 2012; García Fernández, Religiosidad popular 2017. The critiques of the concepts of 'popular piety' or 'popular religion' are innumerable. See, among others, Brown, The Cult of the Saints 1981; Davis, From "Popular Religion" 1982; Vismara, Santuari e pellegrinaggi 2008, p. 26; Holzem, Piété, culture populaire 2010; Balzamo, Religion populaire 2016.

- ^ Duhamelle, Les pèlerins de passage 2000; Stannek, Les pèlerins allemands 2000. For an impressive multi-authored case study that contains much information on one French pilgrim hospital, see Boutry, Reine au Mont Auxois 1997.

- ^ See section 2 on this development with regard to the hajj. Regarding parallel developments in Roman Catholic Europe: Price, Religious Renewal 2018, p. 142; Guth, Geschichtlicher Abriss 1997 [1984], p. 438; Kälin, Schauplatz katholischer Frömmigkeit 2005.

- ^ See, e.g., Boutry / Le Hénand, Pèlerins parisiens 2000; Speth, Katholische Aufklärung 2014 [2008], pp. 17–26; and for an early, much-debated class analysis, Schieder, Kirche und Revolution 1974, pp. 424–430.

- ^ The chevalier de Jaucourt asserted in the Encyclopédie’s entry on pilgrimage that "les courses de cette espece ne sont plus faites que pour[sic] des coureurs de profession, des gueux qui, par superstition, par oisiveté, ou par libertinage, vont se rendre à Notre-Dame de Lorette, ou à S. Jacques de Compostelle en Galice, en demandant l'aumône sur la route." Jaucourt, Pélerinage 2017 [1751–1772], pp. 282f.

- ^ Maes, Le roi, la Vierge 2003; Woeckel, Pietas Bavarica 1992.

- ^ Kizlova, Usamitnennja v natovpi 2019.

- ^ Julia, Pour une géographie 2000, pp. 94–113.

- ^ Lobenwein, Wallfahrt 2013; Delfosse, Pèlerinages 2007.

- ^ For a particularly helpful overview of the "feminization" debate, see Mínguez Blasco, ¿Dios cambió de sexo? 2015. On gender and Roman Catholic pilgrimage in the 19th and early 20th centuries, see most recently Doney, The Persistence 2022.