Germania's Philological Birthplace

In the 15th century, it was probably not easy to regard the countless territories of varying size and constitution which belonged to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation until 1806 as representing a collective national German entity. Indeed, the earliest maps printed at the end of the 15th century did not indicate any territorial boundaries, unless they were defined by coastal areas or rivers. The often already blurred borderlines were also complicated by a complex, centuries-old network of ecclesiastical jurisdictions, which were the cause of on-going tensions between extremely varied interests.1

Other factors, however, also contributed to the highly heterogeneous and rather incomplete basis for the "Germania" narrative: the greatly lamented absence of substantial ancient sources for the Germans' early history;2 the supranational genealogical ties of the ruling European aristocratic families leading back to a shared mytho-biblical early period;3 the universal reference to Rome in all matters of faith over the centuries, before the Reformation; the positing of a "Kingdom of Italy" (Regnum Italicum) that was strongly supported by Maximilian I (1459–1519); and finally, and most particularly, the Italians' Barbaren-Verdikt (verdict of barbarism) with regard to Germany and its inhabitants.

The last three aspects already indicate what is confirmed upon closer inspection: Italy, the county of origin of humanism and the Renaissance, also played a central and varied role in the genesis of the "Model Germania". At first, this was simply due to the fact that the Italian universities of Bologna, Ferrara, Padua and Pavia were among the preferred educational institutions of the early German humanists, a group that can be said to exist since ca. 1450, and was directly involved in the development and dissemination of the "Model Germania".4 At the same time, Enea Silvio Piccolomini (1405–1464)[ ]5– as Pius II (1458–1464) one of the most learned occupants of the papal throne – travelled in the opposite direction. After his earlier service to Emperor Frederick III (1415–1493), he put a spotlight on pre-medieval early German history, mostly with his edition of Germania, written by Publius Cornelius Tacitus (55–116/120) around 100 AD. Piccolomini's work was based on a manuscript transferred to Rome from Hersfeld Abbey and, although his judgement of the early Germans was not entirely positive, it finally provided useful material for addressing the emerging desire to establish the Germans' national and historical origins.6 After the first edition appeared in 1472 in Bologna, a popular university town among the Germans, Friedrich Kreußner (died 1496) printed the first German edition in Nuremberg, whose textual foundation was likely procured directly from Italy by one of the city's early humanists.

]5– as Pius II (1458–1464) one of the most learned occupants of the papal throne – travelled in the opposite direction. After his earlier service to Emperor Frederick III (1415–1493), he put a spotlight on pre-medieval early German history, mostly with his edition of Germania, written by Publius Cornelius Tacitus (55–116/120) around 100 AD. Piccolomini's work was based on a manuscript transferred to Rome from Hersfeld Abbey and, although his judgement of the early Germans was not entirely positive, it finally provided useful material for addressing the emerging desire to establish the Germans' national and historical origins.6 After the first edition appeared in 1472 in Bologna, a popular university town among the Germans, Friedrich Kreußner (died 1496) printed the first German edition in Nuremberg, whose textual foundation was likely procured directly from Italy by one of the city's early humanists.

In any case, the historical impact of Germania is due in particular to the new edition conceived by the famous humanist Konrad Celtis (1459–1508)[

conceived by the famous humanist Konrad Celtis (1459–1508)[ ]. It was published in 1498/1502 in Vienna by Johann Winterburger (1460–1519) as part of a more wide-ranging concept and embellished with Celtis' programmatic poems Germania Generalis

]. It was published in 1498/1502 in Vienna by Johann Winterburger (1460–1519) as part of a more wide-ranging concept and embellished with Celtis' programmatic poems Germania Generalis and De origine, situ, moribus et institutis Norimbergae libellus

and De origine, situ, moribus et institutis Norimbergae libellus .7 To some extent, the ancient text still reads today like a tremendously prescient anticipation – and probably also the foundation – of positive and negative stereotypes concerning a German "national character", whose reception history stretches well into the 20th century. In the land Tacitus considers inhospitable and barren, he also identifies virtues such as modesty, military bravery, bravado, a love of freedom, unconditional loyalty and sincerity, hospitality, a sense of family and monogamy. These positive qualities he contrasts with observations of laziness, carelessness, excessive celebration, an addiction to gaming, drunkenness, a rather primitive agriculture and lifestyle as well as an underdeveloped communal and cultural life.8 Tacitus thus clearly surpasses in clarity and depth the two other main ancient sources regarding "Germania", which were also present during the Middle Ages, but lacked the same pervasive impact. One of these is the so-called German digression

.7 To some extent, the ancient text still reads today like a tremendously prescient anticipation – and probably also the foundation – of positive and negative stereotypes concerning a German "national character", whose reception history stretches well into the 20th century. In the land Tacitus considers inhospitable and barren, he also identifies virtues such as modesty, military bravery, bravado, a love of freedom, unconditional loyalty and sincerity, hospitality, a sense of family and monogamy. These positive qualities he contrasts with observations of laziness, carelessness, excessive celebration, an addiction to gaming, drunkenness, a rather primitive agriculture and lifestyle as well as an underdeveloped communal and cultural life.8 Tacitus thus clearly surpasses in clarity and depth the two other main ancient sources regarding "Germania", which were also present during the Middle Ages, but lacked the same pervasive impact. One of these is the so-called German digression of Gaius Iulius Caesar (100–44 BC) from De bello Gallico, written in 52/51 BC. Although this account is shorter than Tacitus' text, it reflects Caesar's personal experiences and has been available in German since 1507.9 The other source is the map of Magna Germania, which depicts the non-Roman part of "Germania" in a way that was regarded as authentically ancient. It was designed by the apparently German-born Donnus Nicolaus Germanus (ca. 1420–ca. 1490) to accompany his edition of Claudius Ptolemy's (ca. 100–ca. 178 AD) Cosmographia which was being printed since 1467.10

of Gaius Iulius Caesar (100–44 BC) from De bello Gallico, written in 52/51 BC. Although this account is shorter than Tacitus' text, it reflects Caesar's personal experiences and has been available in German since 1507.9 The other source is the map of Magna Germania, which depicts the non-Roman part of "Germania" in a way that was regarded as authentically ancient. It was designed by the apparently German-born Donnus Nicolaus Germanus (ca. 1420–ca. 1490) to accompany his edition of Claudius Ptolemy's (ca. 100–ca. 178 AD) Cosmographia which was being printed since 1467.10

In the early 16th century, the above-mentioned texts by Tacitus and Caesar were read with a clearer understanding of certain key points. These included the stark distinction that Caesar made between Germans and Gauls, and the continuity that was seen to exist – well into the 20th century – between the Germani and the early modern Germans.11 This notion was supported by Tacitus' affirmative answer to the question about the nativeness of the Germans, who had purportedly inhabited their homeland from time immemorial and never been expelled from it. This, in turn, made it easy to make the claim that the Germans had also never been vanquished.12

Konrad Celtis: Between the "Barbaren-Verdikt" and "Pride Work"

The Italian intellectuals' disparaging views about the Germans' lack of culture, their obscure history, habitual crudeness and lack of education13 had already been given expression at the Council of Constance (1414–1418). These prejudices became a source of even greater displeasure14 to the members of the nationes Germanicae, the communities of German students at the Italian universities, culminating into bona fide political issue by around 1500. Konrad Celtis, the most prominent exponent of a now-flourishing German humanism, led the effort to do "pride work" (Stolzarbeit), i.e. to counter these anti-German biases.15 His influence was felt in particular by those "second generation" humanists from 1490 to 1530, who "construed the Italian verdict of barbarism as intentional defamation" and subsequently resorted to a textual "national defense".16

This approach had already been taken, without any obvious indignation, as early as 1493 with one of the most famous German incunabula ever published, the Liber chronicarum (Nuremberg Chronicle, better known as Schedelsche Weltchronik) by the Nuremberg physician and humanist Hartmann Schedel (1440–1514).17 Thus, while the long section on Venice is full of admiration for the international trade metropolis, Schedel also does not neglect to mention that the German city of Trier must be regarded as one of the world's oldest cities, founded after Jerusalem, Babel and Nineveh, but long before Rome.18 However, one still looks in vain for evidence of a "national" focus where it might otherwise be expected. The double-sided world map

by the Nuremberg physician and humanist Hartmann Schedel (1440–1514).17 Thus, while the long section on Venice is full of admiration for the international trade metropolis, Schedel also does not neglect to mention that the German city of Trier must be regarded as one of the world's oldest cities, founded after Jerusalem, Babel and Nineveh, but long before Rome.18 However, one still looks in vain for evidence of a "national" focus where it might otherwise be expected. The double-sided world map that Schedel supplies for his readers at the beginning merely designates Germany, without any special emphasis, as "Saxonia", synonymous with the at the time largest of the German tribes.

that Schedel supplies for his readers at the beginning merely designates Germany, without any special emphasis, as "Saxonia", synonymous with the at the time largest of the German tribes.

Only the map of Germany that Hieronymus Münzer (1437–1508) appends to the work, with recourse to the work of Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464), offers greater clarity.19 Without explicitly mentioning the Italians' Barbaren-Verdikt, he seeks to refute it by presenting a simple yet ultimately unverifiable historical claim: The ennoblement of the Germans in their manners and customs was

... durch nichtz anders denn durch annemung cristenlichen glawbens beschehen. Dann der cristenlich glawb hat von den Teutschen alle barbarische grobheyt vertriben und die Teutschen also gehübscht das yetzo die kriechischen grob und die Teutschen billich lateinisch genent werden.20

Here, then, the process of cultural refinement is not attributed to the advance of spiritual knowledge or current educational reforms (and certainly not to their Italian origins). Instead, the Germans' refinement is ascribed to the mythical and distant process of Christianization and thus endowed with the splendour of an ancient origin.

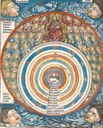

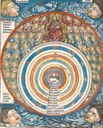

Konrad Celtis subsequently took up this view by acquiring the help of the famous German artist and theorist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) from Nuremberg who designed the programmatic woodcut Philosophia for Celtis' Quatuor libri amorum (Vier Bücher Liebeselegien; Love Elegies in Four Books)

for Celtis' Quatuor libri amorum (Vier Bücher Liebeselegien; Love Elegies in Four Books) . The image condenses to the maximum this legendary and ideologically charged variety of knowledge transfer, which gained importance under the term of translatio studii.21 It is, moreover, one of the few examples in which the direct influence of a humanist on an elaborate illustrative invention can be verified by the sources. Among many other things, Dürer's sketch concisely describes in four medallions the historical path of the transmission of philosophical subject matter: from the ancient Egyptians, via Greeks and Romans to the Germans, who are represented by the famous polymath Albertus Magnus (ca. 1193–1280).22 Because of Magnus' knowledge of alchemy he was considered to be the inventor of gunpowder (another contender for that title was the legendary but fictitious Freiburg Franciscan Berthold Schwarz). Although neither in fact invented gunpowder, its supposed discovery was viewed – along with the invention of movable type printing by Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1400–1468) in the ancient Roman city of Mainz – to be a revolutionary German contribution to the history of Western culture. This reflects not only political, but also technological linkages to the achievements of antiquity.23

. The image condenses to the maximum this legendary and ideologically charged variety of knowledge transfer, which gained importance under the term of translatio studii.21 It is, moreover, one of the few examples in which the direct influence of a humanist on an elaborate illustrative invention can be verified by the sources. Among many other things, Dürer's sketch concisely describes in four medallions the historical path of the transmission of philosophical subject matter: from the ancient Egyptians, via Greeks and Romans to the Germans, who are represented by the famous polymath Albertus Magnus (ca. 1193–1280).22 Because of Magnus' knowledge of alchemy he was considered to be the inventor of gunpowder (another contender for that title was the legendary but fictitious Freiburg Franciscan Berthold Schwarz). Although neither in fact invented gunpowder, its supposed discovery was viewed – along with the invention of movable type printing by Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1400–1468) in the ancient Roman city of Mainz – to be a revolutionary German contribution to the history of Western culture. This reflects not only political, but also technological linkages to the achievements of antiquity.23

These ideas were depicted also in another woodcut – again in greatly condensed form – which also came about due to a suggestion from Konrad Celtis. Hans Burgkmair's (ca. 1500–before 1562) "Imperial Eagle" woodcut portrays a national education programme under the patronage of the "new Apollo", Emperor Maximilian I.24 However, the picture is not explicitly tailored to portray "Germany" and its inhabitants in the narrow sense, but rather the emperor himself, his University of Vienna and the empire. The national aspect thus ultimately recedes behind a rather abstract notion of statehood.

It was also Celtis who went beyond any tangible sources with his project of a poetic description of Germany, which ran through his entire oeuvre like a leitmotif.25 His love elegies symbolically invoked this geographical entity and thus paved the way to a more elevated interpretation: According to Celtis, Germania consists of four parts, and right in the middle lies the mountain Fichtelberg, from which the four major rivers of Germany flow in all directions.26 By exalting elegiacally his fictitious lovers throughout the country, he also indirectly emotionalizes his relationship to the areas themselves. He pays homage to something that before seemed hardly praiseworthy: the "country" in which he was born, where he lived, where he often wandered and where he hoped to have a beneficial impact. If it is possible to identify something like the birth of a love of country – a love that exceeds the subjective, emotional and immediate "homeland" of one's birth and childhood – then it can probably be found in Celtis' Quatuor libri.

Maximilian I, the "Holy Roman Empire" and "Germania"

Unlike in Italy, where contents and forms of antiquity went hand in hand – especially in architecture and the visual arts – humanism and the reception of antiquity in Germany were more philological, as well as political, in nature. Whenever the Roman heyday under Caesar or Augustus (63 BC–14 AD) were allegorically evoked in the Holy Roman Empire, they served also as an allusion to the high expectations associated with the reign of Emperor Maximilian I. These concerned the awaited flourishing of the arts and sciences and the German-Roman emperor's primacy among all Christian rulers. During all of his life Maximilian was thus the preferred figure for representing the national and patriotic hopes of his immediate and wider intellectual environment. Already before 1500, a dedicatory broadsheet from the Regensburg humanist Janus Tolophus (1429–1503) portrayed him as "Hercules Germanicus".27

Like his erudite circle, the Emperor also had an extremely ambivalent relationship with Italy, which owed much to conflicting experiences. Despite many failures, he vehemently fought to exert his influence and the influence of his empire in Italy. Even if the so-called Regnum Italicum or "Kingdom of Italy" – that is, the part of Italy that was claimed by the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire – was a more pressing political issue in the High Middle Ages,28 it remained a focal point for Emperor Maximilian, particularly after his wedding to the daughter of the Milanese Duke, Bianca Maria Sforza (1472–1510), which took place in 1494. The claim on Italia, quae mea est ("my Italy") chiefly came to light in the struggle with the papacy and Venice concerning Maximilian's hoped-for coronation in Rome, a hope that was finally abandoned in 1508, and in the battles for the imperial fiefdom of Milan.29

It should be emphasized that Maximilian inextricably merged the interests of the House of Habsburg with those of the empire, often to the detriment of the latter. He by no means followed a recognizable, stringent ideology – certainly none that could be called national. Rather, the representation of his own superiority stemmed from the dignity of his office, established by Iulius Caesar, and – often closely interwoven with this – from the perceived primeval origin of the House of Habsburg. For this reason, he had his secretaries, poets and artists give his political, dynastic and military objectives the most expedient ideological lustre possible.30

A decisive impetus in this regard came from Alsace. A region where the emperor's dynastic interests were more or less aligned with those of the empire, Maximilian had reigned there since 1490 as "Landgrave of Alsace".31 Unlike the border territories of the Habsburg Netherlands, the Electorate of Bohemia or Switzerland, which had loose and increasingly weak relations with the empire, Alsace was an area that was presented as decidedly "reichisch" (belonging to the core territories of the empire) as a result of constant threats from Burgundian, and later French, claims. Alsace was also the "patria" of known historians and writers such as Jakob Wimpfeling (1450–1528) or Sebastian Brant (1457/1458–1521).32 Wimpfeling is worth highlighting in particular: his Germania, which appeared in Latin and German as part of an anthology in 1501 in Strasbourg,33 was an early standard work of national historiography, whose thrust was primarily anti-French.34

Dürer and Hutten: A Comparative View

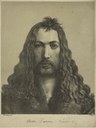

It would be overly simplistic to draw a direct line from the decades around 1500 to the hypernationalism of the 19th and 20th centuries.35 This is because the Reformation soon created at least two opposing value systems, in which the spirit of nationalism was exploited mainly on the Protestant side. Many individual motives and narratives, however, can be identified through all historical and cultural transformations. This phenomenon is best illustrated by the figure of the artist and theorist Albrecht Dürer , for also in his case – for Dürer himself as well as for his later admirers – Italy represented a main point of friction. This was mainly due to the fact that in the visual arts Italian forms were generally adopted very reluctantly in Germany and usually made to fit stylistically with what might be referred to as the local "diffraction pattern". This pattern, however, was thought to reflect a synthesis and enhancement of what had been discovered, and can also be interpreted as a conscious rejection of the influence of the Italian Renaissance.36

, for also in his case – for Dürer himself as well as for his later admirers – Italy represented a main point of friction. This was mainly due to the fact that in the visual arts Italian forms were generally adopted very reluctantly in Germany and usually made to fit stylistically with what might be referred to as the local "diffraction pattern". This pattern, however, was thought to reflect a synthesis and enhancement of what had been discovered, and can also be interpreted as a conscious rejection of the influence of the Italian Renaissance.36

Such an observation is certainly plausible for the time leading up to the mid-16th century. However, it must be qualified with regard to the next few decades, for the "Renaissance model" of the Italian painter and writer Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) became a master narrative from 1550 that extended far beyond art history. With great success (which has only been critically examined in recent years), this model propagated the notion that the cultural tradition of the ancient world had been interrupted by the sinister "Gothic" Middle Ages and told of its glorious, and in all respects superior, revival in Florence.37 In point of fact, however, neither Dürer himself, nor the German artists of his generation had ever been to Florence or Rome. And precisely in Dürer's case, the influences on his art were less formal than theoretical in nature; influences which he absorbed mainly during his second sojourn in Venice (1505–1507). It was here – and only here – that he actually once employed the signature Albertus durer germanus,38 thereby underlining his German heritage, as defined by his humanist friends Brant and Celtis. At the same time, however, and this was probably the more important matter to him, he demonstrated his active participation in the contemporary intellectual discourse.39

Quite astonishingly, then, before Martin Luther (1483–1546) would rise to become a national figure and role model![Doctor Martini Luthers offenliche Verhör IMG Doctor Martini Luthers offent=||liche verho[e]r zu[e] Worms im[m] Reychstag/||Red vnnd widerred/am.17.tag||Aprilis/im[m] jar.1521.||beschehen, Titelblatt, Holzschnitt mit Typendruck, Augsburg : Sigmund Grimm und Max Wirsung, 1521, unbekannter Augsburger Künstler; Bildquelle: VD 16 L 3653, Benzing/Claus Nr. 928, Sächsische Landesbibliothek - Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, Hist. eccl. E 319,20, http://digital.slub-dresden.de/id350378460.](./illustrationen/wittenberger-reformation-bilderordner/doctor-martini-luthers-offenliche-verhoer-img/@@images/image/thumb) (at least for the Protestants), his precursor in this regard was not a ruler, poet or theologian, but rather the artist Albrecht Dürer. A sense of national superiority had already crystallized around his person and his work around 1500, when Celtis had elevated him to the "German Apelles". And after Dürer's visit to the Netherlands in 1520/1521, he was idealized there as Germanorum decus (the glory of Germany). This designation could be read until 1852 as part of the inscription of his bust

(at least for the Protestants), his precursor in this regard was not a ruler, poet or theologian, but rather the artist Albrecht Dürer. A sense of national superiority had already crystallized around his person and his work around 1500, when Celtis had elevated him to the "German Apelles". And after Dürer's visit to the Netherlands in 1520/1521, he was idealized there as Germanorum decus (the glory of Germany). This designation could be read until 1852 as part of the inscription of his bust , made around 1563, on the former façade of the Antwerp painters' guild.40 Dürer's elevation to a representative of "Germania" is, however, not surprising, considering that he was known to, or friends with, all of the literary protagonists of "Germania", including Celtis, Brant, Wimpfeling and Schedel.

, made around 1563, on the former façade of the Antwerp painters' guild.40 Dürer's elevation to a representative of "Germania" is, however, not surprising, considering that he was known to, or friends with, all of the literary protagonists of "Germania", including Celtis, Brant, Wimpfeling and Schedel.

Dürer was therefore no less of an inspiration than his contemporaries Martin Luther , Hans Sachs (1494–1576) or Ulrich von Hutten (1488–1523) to the Romantic nationalism that began to emerge in Germany at the beginning of the 19th century. Although the figure of Dürer has not played a significant role, at least since the 1970s, in the increasing national efforts in Germany to come to terms with the past, the reputation of his contemporary Hutten experienced a late bloom in the German Democratic Republic as a patriotic champion of the Reformation, an aristocratic revolutionary and a friend of the peasants.41 After the end of the German Democratic Republic in 1990 one of Germany's last patriotic narratives, whose earliest proponents had lived at the time of the first edition of Tacitus' Germania, became obsolete.

, Hans Sachs (1494–1576) or Ulrich von Hutten (1488–1523) to the Romantic nationalism that began to emerge in Germany at the beginning of the 19th century. Although the figure of Dürer has not played a significant role, at least since the 1970s, in the increasing national efforts in Germany to come to terms with the past, the reputation of his contemporary Hutten experienced a late bloom in the German Democratic Republic as a patriotic champion of the Reformation, an aristocratic revolutionary and a friend of the peasants.41 After the end of the German Democratic Republic in 1990 one of Germany's last patriotic narratives, whose earliest proponents had lived at the time of the first edition of Tacitus' Germania, became obsolete.

As a rather ironic epilogue, "Hermann der Cherusker", one of the most important champions of German national pride , owed his own literary revival well into the 20th century to Hutten. In Hutten's Arminius (probably written around 1517, but first published posthumously together with Tacitus' Germania in 1528), Hermann (ca. 18 BC–21 AD) is celebrated in dialogue form as the conqueror of the Roman legions, a freedom fighter and the epitome of German invincibility. Recent research, though, has found evidence that the hero's portrayal, done in the tradition of the ancient satirist Lucian (120–180), contains many ironic distortions.42

, owed his own literary revival well into the 20th century to Hutten. In Hutten's Arminius (probably written around 1517, but first published posthumously together with Tacitus' Germania in 1528), Hermann (ca. 18 BC–21 AD) is celebrated in dialogue form as the conqueror of the Roman legions, a freedom fighter and the epitome of German invincibility. Recent research, though, has found evidence that the hero's portrayal, done in the tradition of the ancient satirist Lucian (120–180), contains many ironic distortions.42

Thomas Schauerte

Appendix

Sources

Caesar, Gaius Julius: Julius der erst Römisch Keyser von seinem Kriege, translated by Matthias Ringmann, Strassburg 1507. URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00001890-3 [2021-09-16]

Donnus Nicolaus Germanus (ed.): Cosmographia Claudii Ptolomaei Alexandrini, Bologna 1467.

Celtis, Konrad: De origine, situ moribus et institutis Norimbergae libellus, Nuremberg 1502. URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00007499-6 [2021-09-16]

Füssel, Stephen (ed.): Hartmann Schedel: Weltchronik. Kolorierte Gesamtausgabe von 1493, Cologne et al. 2001.

Müller, Gernot Michael: Die "Germania generalis" des Conrad Celtis: Studien mit Edition, Übersetzung und Kommentar, Tübingen 2001 (Frühe Neuzeit 67).

Stückelberger, Alfred et al. (eds.): Ptolemaios: Handbuch der Geographie (Griechisch-Deutsch), Basel 2006.

Tacitus, Cornelius: Germania, ed. by Manfred Fuhrmann, Stuttgart 1972.

Bibliography

Blum, Gerd: Giorgio Vasari: Der Erfinder der Renaissance, Munich 2011. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1168q7s [2021-09-16]

Borries, Emil von: Wimpfeling und Murner im Kampf um die ältere Geschichte des Elsasses: Ein Beitrag zur Charakteristik des deutschen Frühhumanismus, Heidelberg 1926. URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hbz:061:1-16381 [2021-09-16]

Glei, Reinhold F.: Der deutscheste aller Deutschen? Ironie in Ulrich von Huttens Arminius, in: Reinhold F. Glei (ed.): Ironie: Griechische und lateinische Fallstudien, Trier 2009 (Bochumer Altertumswissenschaftliches Colloquium 80), pp. 265–282.

Gruber, Joachim: Art. "Germanen. III. Der Germanenbegriff im Mittelalter", in: Lexikon des Mittelalters 4 (1989), col. 1343f.

Hirschi, Caspar: Wettkampf der Nationen: Konstruktion einer deutschen Ehrgemeinschaft an der Wende vom Mittelalter zur Neuzeit, Göttingen 2005.

Hoppe, Stephan et al. (eds.): Stil als Bedeutung in der nordalpinen Renaissance: Wiederentdeckung einer methodischen Nachbarschaft, Regensburg 2008.

Jäger, Lorenz: Eine deutsche Unheilsgeschichte, Rezension zu: Krebs, Christopher B.: Ein gefährliches Buch: Die "Germania" des Tacitus und die Erfindung der Deutschen, Munich 2012, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 10/03/2012, no. 60, p. L19.

Keller, Hagen: Art. "Lehen: Lehenswesen, Lehnrecht", in: Lexikon des Mittelalters 5 (1991), col. 1811ff.

Keller, Hagen: Der Blick von Italien auf das "römische" Imperium und seine "deutschen" Kaiser, in: Bernd Schneidmüller et al. (eds.): Heilig – Römisch – Deutsch: Das Reich im mittelalterlichen Europa, Dresden 2006, pp. 286–307.

Kleineberg, Andreas et al. (eds.): Germania und die Insel Thule: Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios' "Atlas der Oikumene", Darmstadt 2010.

Köbler, Gerhard: Art. "Mailand", in: Gerhard Köbler: Historisches Lexikon der deutschen Länder: Die deutschen Territorien vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, Munich1990, pp. 321f.

Köbler, Gerhard: Historisches Lexikon der deutschen Länder: Die deutschen Territorien vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, Munich 1992.

Krapf, Ludwig: Germanenmythus und Reichsideologie: Frühhumanistische Rezeptionsweisen der taciteischen "Germania", Tübingen 1979 (Studien zur deutschen Literatur 59).

Krebs, Christopher B.: Ein gefährliches Buch: Die "Germania" des Tacitus und die Erfindung der Deutschen, Munich 2012.

Krebs, Christopher B.: Negotiatio Germaniae: Tacitus' Germania und Enea Silvio Piccolomini, Giannantonio Campano, Conrad Celtis und Heinrich Bebel, Göttingen 2005.

Luh, Peter: Kaiser Maximilian gewidmet: Die unvollendete Werkausgabe des Conrad Celtis und ihre Holzschnitte, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2001 (Europäische Hochschulschriften, Reihe 28, vol. 377).

Luh, Peter: Der "allegorische Reichsadler" von Conrad Celtis und Hans Burgkmair: Ein Werbeblatt für das Collegium Poetarum et Mathematicorum in Wien, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2002 (Europäische Hochschulschriften, Reihe 28, vol. 390).

Mende, Matthias: GERMANORUM DECVS: Zur Bildnisbüste Albrecht Dürers im Museum Vleeshuis in Antwerpen, in: Christian Hecht (ed.): Beständig im Wandel: Innovationen – Verwandlungen – Konkretisierungen: Festschrift für Karl Mösenender zum 60. Geburtstag, Berlin 2009, pp. 121–128.

Mertens, Dieter: Die Instrumentalisierung der "Germania" des Tacitus durch die deutschen Humanisten, in: Beck, Heinrich (ed.): Zur Geschichte der Gleichung "germanisch – deutsch": Sprache und Namen, Geschichte und Institutionen, Berlin et al. 2004, pp. 37–101. URL: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:25-opus-27632 [2021-09-16]

Mertens, Dieter: Kaiser Maximilian und das Elsass, in: Otto Herding (ed.): Die Humanisten in ihrer politischen und sozialen Umwelt, Boppard 1976 (Kommission für Humanismusforschung, Mitteilung 3), pp. 177–201.

Möller, Steffen: Nicolaus Cusanus als Geograph, in: Harald Schwaetzer et al. (eds.): Das europäische Erbe im Denken des Nikolaus von Kues: Geistesgeschichte als Geistesgegenwart, Munster 2008, pp. 215–227.

Müller, Jan-Dirk: Gedechtnus: Literatur und Hofgesellschaft um Maximilian I., Munich 1982. URL: https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00046030-0 [2021-09-16]

Schauerte, Thomas: Die deutschen Apelliden: Anmerkungen zu humanistischen und nationalen Aspekten in höfischen Bildwerken der Dürerzeit, in: Matthias Müller et al. (eds.): Apelles am Fürstenhof: Facetten der Hofkunst um 1500 im Alten Reich, Berlin 2010, pp. 34–43.

Schauerte, Thomas: Die Ehrenpforte für Kaiser Maximilian I.: Dürer und Altdorfer im Dienst des Herrschers, Munich et al. 2001 (Kunstwissenschaftliche Studien 95).

Schauerte, Thomas: Von der "Philosophia" zur "Melencolia I": Anmerkungen zu Dürers Philosophie-Holzschnitt für Konrad Celtis, in: Franz Fuchs (ed.): Konrad Celtis und Nürnberg: 500 Jahre Amores, Nürnberg 2004 (Pirckheimer-Jahrbuch 2003), pp. 117–139.

Sottili, Agostino: Nürnberger Studenten an italienischen Renaissance-Universitäten mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Universität Padua, in: Volker Kapp et al. (eds.): Nürnberg und Italien: Begegnungen, Einflüsse und Ideen, Tübingen 1991 (Erlanger romanistische Dokumente und Arbeiten 6), pp. 49–103.

Wiener, Claudia et al. (eds.): Amor als Topograph: 500 Jahre Amores des Conrad Celtis: Ein Manifest des deutschen Humanismus, Schweinfurt 2002.

Wiesflecker, Hermann: Kaiser Maximilian I: Das Reich, Österreich und Europa an der Wende zur Neuzeit, Vienna et al. 1971–1986, vol. 1–5.

Wirth, Günter: Nachwort, in: Otto Flake: Ulrich von Hutten, Berlin (East) 1983, pp. 364–375.

Wood, Christopher S.: Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art, Chicago 2008.

Notes

- ^ This situation is described in the following manner by one of the best authorities on the subject: "Der Verband des Heiligen Römischen Reichs deutscher Nation ist derart vielfältig und unterschiedlich, daß es bereits erhebliche Mühe bereitet, seine Teile zu erfassen." ("The alliance of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation is so complex and diverse that compiling its parts causes considerable difficulty", transl. by C. R.), cf. Köbler, Historisches Lexikon 1992, S. X. For the period under consideration here, between 328 and about 400 principalities can be found in the empire registries for the years 1489 and 1521 (Köbler, Historisches Lexikon 1992, S. X).

- ^ On the scarcity of sources from the High Middle Ages, cf. Gruber, Art. "Germanen. III." 1989.

- ^ The sons of Noah spread out over the three continents, known at the time (Japheth: Europe, Shem: Asia; Ham: Africa). After the fall of Troy, its defenders were scattered around the world and became the founding fathers of the European aristocratic Houses.

- ^ Particularly noteworthy are Peter Luder (Ferrara), the Dutchman Rudolf Agricola (Pavia, Ferrara), Hartmann Schedel (Padua), Johannes Pirckheimer (Padua) and Sigismund Meisterlin (Padua); cf., for instance, Sottili, Nürnberger Studenten 1991.

- ^ Enea thus points out in his own seminal work on Germany in 1457/1458 – which first appeared in Leipzig in 1496 under the title De ritu, situ, moribus et conditione Germaniae and was later also known as Germania – that the Germans made human sacrifices; cf. Mertens, Instrumentalisierung 2004, pp. 70f., who rightly mentions the systematic suppression of this fact in all the editions of the period considered in this article. However, the suppression appears to be legitimated by Caesar's explicit statement in De bello Gallico that the Germans were not particularly keen on human sacrifice (6.21 "... neque sacrificiis student.").

- ^ Of still vital importance to this issue: Krapf, Germanenmythus 1979; Krebs, Negotiatio Germaniae 2005.

- ^ Celtis, De origine 1502. On this matter, and also essential to the discussion that follows, cf. Müller, "Germania generalis" 2001.

- ^ Tacitus, Germania 1972.

- ^ Caesar, Julius der erst Römisch Keyser 1507.

- ^ Donnus Nicolaus Germanus, Cosmographia 1467; also worth mentioning here is the scholarly debate on the early historical place names in the non-Roman occupied part of Germania, cf. Stückelberger, Ptolemaios 2006; Kleineberg, Germania 2010.

- ^ Mertens, Instrumentalisierung 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Celtis emphasizes all this explicitly in his Germania Generalis, cf. the edition of Müller, "Germania generalis" 2001, p. 94.

- ^ Müller, "Germania generalis" 2001, pp. 243–249.

- ^ On the nationes conflict at the Council of Constance, cf. Hirschi, Wettkampf 2005, pp. 141ff. This article is indebted to numerous suggestions from Hirschi's study, which also offers a detailed table of contents that allows readers a quick access to more information on many of the aspects mentioned here.

- ^ The term apparently comes from the Nuremberg cultural studies expert Hermann Glaser, who devised it in the context of the German debate from the 1960s about guilt and coping vis-à-vis the crimes of National Socialism and thus as a complement to the concept of "Trauerarbeit" (grief work) by Sigmund Freud (1856–1939).

- ^ Hirschi, Wettkampf 2005, p. 269 (transl. by C.R.).

- ^ Facsimile of the German edition: Füssel, Hartmann Schedel 2001.

- ^ Cf. Füssel, Hartmann Schedel 2001, fol. XXIII.

- ^ The map was first published as a copper engraving in 1491 in Eichstätt, cf. Möller, Nicolaus Cusanus 2008.

- ^ Füssel, Hartmann Schedel 2001, fol. 267v: " ... only made possible through their acceptance of the Christian faith. The Germans' Christian faith hence purged them of all their barbaric crudeness and ennobled them to such a degree that the Greeks were now deemed crude and the Germans rightfully called Latin.", transl. by C.R.

- ^ Cf. Luh, Maximilian 2001, pp. 64–122.

- ^ Schauerte, "Philosophia" 2004, pp. 117–139.

- ^ Cf. Wood, Forgery 2008, pp. 64f.; Hirschi, Wettkampf 2005, pp. 283–288.

- ^ Luh, Der "allegorische Reichsadler" 2002.

- ^ Müller, "Germania generalis" 2001, p. 472.

- ^ This also constitues the framework for the magnum opus among his completed writings, the Quatuor libri amorum from 1502, cf. also Wiener, Amor 2002.

- ^ Cf. Luh, Maximilian 2001, pp. 334–348.

- ^ As far as it may be ascertained, the continued and long-term effects of this phenomenon have not been adequately studied, cf. Keller, Der Blick von Italien 2006; Keller, Art. "Lehen. Lehenswesen, Lehnrecht" 1991, pp. 321f., especially no. 2: "Reichsitalien". Cf. also Köbler, Art. "Mailand" 1990.

- ^ Wiesflecker, Kaiser Maximilian I. 1986, vol. 5, pp. 414f. On Maximilian's restitution attempts, Wiesflecker, Kaiser Maximilian I. 1972, vol. 2, pp. 9–26. In the escutcheons of the "Ehrenpforte" ("Arch of Maximilian I") – a giant woodcut printed in 1517/1518 – there are the shields of: Lower Lombardy, Sicilia citra Pharum (kingdom of Naples), Sicilia ultra Pharum (kingdom of Sicily), Naples (kingdom of the two Sicilies), Sardinia, Calabria and Apulia, cf. Schauerte, Die Ehrenpforte 2001, A 2, no. 8, 61, 62, 64, 72, 88, 89.

- ^ Müller, Gedechtnus 1982, passim, especially Chapter II, pp. 48–79.

- ^ Even if only together with approximately 30 other imperial estates in Upper and Lower Alsace.

- ^ Cf. Mertens, Kaiser Maximilian 1976, pp. 182ff.

- ^ Bilingual edition: Borries, Wimpfeling und Murner 1926.

- ^ Cf. also the criticism in Krapf, Germanenmythus 1979, pp. 44ff., who refers to the Italian reception of Tacitus.

- ^ Cf. the nuanced criticism in Hirschi, Wettkampf 2005, pp. 489–501.

- ^ Cf. Hoppe, Stil 2008.

- ^ Cf. Blum, Giorgio Vasari 2011. This Renaissance concept is responsible for the creation of German art-historical institutes abroad in Florence (1897) and Rome (1913), which were the only ones of their kind until the founding of the German Forum for Art History in Paris in 1997. Wood, Forgery, 2008, p. 66, recently put forward the plausible argument that in a country like Germany, where the existence of the "Middle Ages" as such was not even recognized (and certainly not in the sense of Giorgio Vasari), many were convinced of an unbroken continuity since ancient Roman times and hence the need for a "renaissance" in the strict sense of the word would not have even been contemplated.

- ^ On the Madonna mit dem Zeisig (Madonna with the Siskin, Staatliche Museen Berlin, Gemäldegalerie): Albertus durer germanus faciebat post virginis partum 1506 AD.

- ^ On the surprisingly small influence of Germania and its subsequent publications on contemporaneous German art, cf. Schauerte, Apelliden 2010.

- ^ Cf. Mende, GERMANORUM DECVS 2009. The fountain by Carl Alexander Heideloff (1789–1865) – the Dürer-Pirckheimer-Brunnen – was dedicated in Nuremberg in 1821, the same year as Johann Gottfried Schadow's (1764–1850) Luther Memorial in Wittenberg, and is supposedly the first public memorial site for an artist.

- ^ Cf., for instance, Wirth, Nachwort 1983.

- ^ Glei, Der deutscheste aller Deutschen? 2009; Krebs, Gefährliches Buch 2012. In this regard, cf. the justifiably critical review of Jäger, Unheilsgeschichte 2012.

![Doctor Martini Luthers offenliche Verhör IMG Doctor Martini Luthers offent=||liche verho[e]r zu[e] Worms im[m] Reychstag/||Red vnnd widerred/am.17.tag||Aprilis/im[m] jar.1521.||beschehen, Titelblatt, Holzschnitt mit Typendruck, Augsburg : Sigmund Grimm und Max Wirsung, 1521, unbekannter Augsburger Künstler; Bildquelle: VD 16 L 3653, Benzing/Claus Nr. 928, Sächsische Landesbibliothek - Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, Hist. eccl. E 319,20, http://digital.slub-dresden.de/id350378460.](./illustrationen/wittenberger-reformation-bilderordner/doctor-martini-luthers-offenliche-verhoer-img/@@images/image/thumb)