Introduction

From the very beginning, "mission", in the sense of a universal trans-cultural dissemination of faith, was an essential part of Christianity. In subsequent centuries and epochs missionary activity took on many forms, from processes of micro-communication via a capillary network that spread into nearby regions, to the professional preaching of the Gospel by trained missionaries.

The modern era that we will be examining, despite encompassing a period of five hundred years (1450–1950), makes up only one fourth of the history of the Christian mission. It is characterised primarily by a transcontinental movement that, beginning in Europe, carried Christianity to the Americas, Asia and Africa.1 But, even in the epochs that preceded it, various cultures had developed forms of intellectual and inter-cultural communication upon which the modern mission could build. The foundation and pre-requisite for the European transcontinental missionary movement in the modern era were Christianity's rootedness in Europe and the unity of the Roman Catholic Church with its centre in Rome.

Christianity had spread throughout the European continent during a thousand year process that extended from Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages. With its variety of missionary methods (e.g. peaceful mission, mission by coercion and the conversion of tribes by first converting the ruler), Christianity had reached all European peoples. It extended from Greece to Scandinavia and Iceland; it stretched from Ireland in the far west to Eastern Europe's West Slavic and Baltic peoples. This process had brought forth European Christianity which, in turn and by stages, initiated missionary activity beyond Europe's borders. The religious missionary enterprise was generally tied to the economically driven power politics involved in European overseas expansion,2 a process of globalisation which compacted space and time and was begun in the early modern period by the powers of the Iberian Peninsula, Portugal and Spain, and continued later on by other European maritime powers and by the United States of America.

Starting from the Eastern Mediterranean the Christian mission moved not only westward but also east. Thus, in addition to the missionary activity of Roman Catholic Christianity, oriental Christianity, primarily the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East – with its later centre in Baghdad – developed a comparable missionary movement towards Persia and India, and along the Silk Road into Central Asia and China. However, in contrast to the success of Christianity in the west, oriental Christianity was unable to put down extensive roots in the vast expanses of the east: probably because its capacity for inculturation was inadequate and it lacked the support of worldly rulers. This, and other reasons, led to its diminishing importance and, as a result, it has only survived fragmentarily.3

A new terminology was created in the early modern era that replaced the concepts of the Middle Ages and quickly became a part of the general language. Neither Late Antiquity nor the Middle Ages had had a unified concept to designate missionary activity and had used many different terms to describe it. Thus the sources speak of the "proclamation of the Gospel" (promulgatio Evangelii) or of the "propagation of faith" (propagatio fidei). But they also speak of "preaching to the peoples" (praedicatio gentium), of the concern for salvation (De procuranda salute), of the "conversion of the infidels" (conversio infidelium) and of "Gospel work" (labor evangelicus). The neologism "mission", coined in early Jesuit circles, denoted at first the personal or institutional mission of those who had been commissioned by a Church authority. From this term the plural "missions" was derived which designates the task itself, as well as the intended geographical area. Thus the concept became a terminus technicus that soon entered into official language and theological literature. Widely used also in ecumenical and historical contexts, it acquired, however, an increasingly negative connotation in the wake of de-colonisation in the middle of the 20th century.4

But the increasing general use of the concept should not obscure the confessional differences in mission theory and practice which were closely linked to the political and ecclesiastical conditions of the time. In the Age of Discovery, on the threshold to the modern era, a dynamic missionary activity developed within the framework of the Catholic Church. It took advantage of newly discovered sea routes that, circumnavigating Africa, led to Asia, or, sailing across the Atlantic, led to the Americas. The missions took place within the framework of this expansion and under the patronage that had been granted to the rulers of the Iberian Peninsula by the Pope. It obliged them to install the Church in the newly discovered lands, to finance missions and to staff them with well-educated personnel. However, this task, which the Catholic monarchs of the Iberian maritime powers took a personal and serious interest in, could hardly have been carried out, had there not been well trained and highly motivated ascetic members of numerous religious orders, who had dedicated themselves to missionary work. These missionaries, at first members of exclusively male religious orders, came from the mendicant orders of the millenarian Franciscans (Ordo Fratrum Minorum) and Dominicans (Ordo Praedicatorum), but also from the Augustinians, Capuchins, Mercedarians and Carmelites. A particularly important and innovative role in the missions to Asia and the Americas was played by the recently founded (1540) Order of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits).

In contrast to the Catholic missions, and despite individual exceptions, the denomination that emerged from the Reformation failed to develop large scale missionary activity in their first two hundred years of existence. This was probably due to the fact that the confessions were largely confined to non-coastal regions, and that the new confessions had disbanded the religious orders. But theological reasons may have also played a role: the so-called "Great Commission" (Matthew 28: 18–20) was regarded as to have been already carried out by the Apostles, or to be restricted to the parishes. The Protestant world mission first came into being when institutional frameworks and personal resources, similar to the ones that the Catholics had, became available. At the end of the 18th century, as the strength of the Iberian powers waned, the Catholic missions also suffered a decline. At the same time the competing Protestant maritime and colonial powers of Holland, England and Denmark expanded their overseas holdings. Under these conditions Protestant missionary activity also came into existence, beginning with the short-lived Seminarium Indicum in Leyden (1622) that was supported by the Dutch chartered United East India Company (VOC). Revivalist movements, such as pietism or the Moravian Church, also developed an interest in missionary activity. Both religious and colonial interests were combined in an exemplary manner in the Danish and English Halle mission to South India with its pietist protagonist Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg (1682–1719)[

The missionary activity of the Russian Orthodox Church went hand in hand with Russia's mid-sixteenth century expansion to the south that resulted in the conquest of the Tatar Khanate at Kazan and Astrakhan by Ivan IV the Terrible (1530–1584) and the – to a certain level – coercive conversion of the Muslim population. During the expansion to the east in the 18th century, as Tsar Peter I (1672–1725) pursued the exploration of Siberia, and as the expedition into Eastern Siberia led to the discovery of Alaska during the reign of Tsarina Catherine II (1729–1796)[

Epochal Contexts and Missionary Interaction

In the modern era, the interaction brought about by missionary activity no longer took place in Europe, (with the exception of efforts on the part of the confessions to win converts from one another). Rather the space in which interaction took place was so enlarged that in the course of the modern era religious relationships were established and deepened in all the other inhabited parts of the world, i.e. Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Australia and Oceania. Taken as a whole the missionary activities of the various confessions were an independent factor in the process of modernisation and globalisation in this era that saw the change from a European Christianity (orbis christianus) to a Christianity with worldwide roots. Still, generally speaking, missions remained tied to political frameworks and economic interests, which they often had the function of legitimising.

Prepared by the cultural and artistic developments of the Renaissance where, based on such discoveries as the central perspective, a new artistic and philosophical legitimation was given to the freedom and dignity of the modern human being (Pico della Mirandola [1463–1494] being the perfect embodiment), missionary activity was further stimulated by the Portuguese voyages of discovery to the east and the Spanish voyages to the west. The awareness of new worlds re-awakened the interest in missionary activity, which was now also influenced by the ascetic and scientific ideas propagated by the newly developed humanism. The drive towards missionary activity also gained a new impulse from the knowledge that many people hitherto unknown to Europeans were not baptized. For, in keeping with the view of the time's Augustinianism, unless such people were rescued in the "eleventh hour"(Matthew 20: 6), they ran the risk of damnation. Never before had a religion been able to influence such a big part of humanity – so one judgement regarding the centuries of progress in the proliferation of Christianity between 1500 and 1800.5

Mission in Asia

On their way east, in search of lucrative trade, the Portuguese circumnavigated Africa and in 1482 discovered the Congo estuary. The ruler of the nearby ancient African kingdom, the Manikongo, agreed to be baptised and thereby initiated the Christianisation of his kingdom.

The expansion of the Portuguese commercial empire, with its trading stations in Asia (Estado da Índia), took place under royal patronage (padroado) over the Church and its missionaries. Goa (India) and, later, Macao (China) developed into both political and ecclesiastical centres. From these vantage points missionary activity extended, not only to the Indian subcontinent but also to China and Japan in the Far East. The early modern mission to Asia was led by the Jesuit Francisco Javier (Franz Xaver, 1506–1552)[

In Asia Christian missionaries generally encountered highly developed civilizations and religions to which the missionary projects tried to closely attach themselves. The Catholic initiatives in India, Japan and China between the 16th and 18th centuries sought therefore not merely an external accommodation to native cultures, but also entered into an inter-cultural exchange and spiritual dialogue. The main actors here were Italian missionaries such as Alessandro Valignano (1539–1606) (Japan), Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) (China), and Roberto de Nobili (1577–1656) (South India), whose vast knowledge of the humanities and the natural sciences was an integral part of the mission concept and facilitated the making of cultural ties as their interaction partners in China, where a conversion "from above" was pursued, were Confucian scholars and government officials. At times this interaction took place at the highest level, for example in the 17th century when Adam Schall von Bell (1592–1666) developed a paternal relationship to the young Ming Emperor Shunzhi (1638–1661), and Ferdinand Verbiest (1623–1688) became a good friend of the great Qing Emperor Kangxi (1654–1722).

The Church's efforts to free the mission from colonial and governmental ties and to make it once again a primarily religious undertaking, reached their culmination in the founding of the Roman Congregation De propaganda fide (1622) which began the process of decolonising and freeing the mission from Euro-centricity – a task that took centuries to accomplish.

Protestant missionary activities made their appearance in Asia at the beginning of the 18th century. Their effectiveness was closely connected to the rise of the Protestant maritime powers of Holland, England and Denmark, and to such chartered companies as the English East India Company. Of decisive importance for their success were mission societies whose members pioneered such fields as linguistics and Bible translation. A large number of missionary societies emerged in the 19th century; more than fifty are on record in the anglophone area alone, among them one from the United States which began as a federation of college students, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (1810).

In the Pacific a special role was played by the Philippines which had been conquered for the Spanish crown in 1571 and named for the Spanish king. Missionary activity began shortly thereafter, carried out by various religious orders that stood under the King's patronage, and which took up the methods that had generally been used in the Americas. Trying to avoid previous errors, they combined the building of educational and healthcare facilities with measures to protect the people. With the exception of the Muslim areas south of the main island of Mindanao, this mission brought about the almost complete Christianisation of the Philippines. The independence movement which began in the 19th century, and in which some of the native clergy took part, led on the one hand to schismatic independent churches and, on the other, to the beginnings of Protestant missionary activity. The latter was occasioned by the United States' occupation of the Philippines during the Spanish-American War (1898), a measure that the American president also justified with reference to "Christianizing" the Philippines.

Conquest and Missionary Work in the Americas

In the Americas missionary activity took place in the wake of European expansion during the early modern period. However, in contrast to the pattern in Asia, it occurred in the form of the conquista (conquest) of entire countries and regions, which were then integrated into the empires of the Iberian powers. Thus the joining of sword and cross, economic exploitation and religious mission, determined the nature of European discovery, conquest, occupation and seizure of the New World.

Under papal influence the two rival Iberian powers had agreed in the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494)

Mainly, the practical bearers of the colonial mission in the Americas were the relatively independent and supra-national religious orders. In the first rank were the Franciscans, who from the time of the High Middle Ages had gathered experience in Asia and Africa. Between the 16th and the 18th century they accounted for more than half of the 15,000 missionaries sent to the colonies. The Franciscans were followed by the recently founded Jesuits and by the Dominicans. The spiritual orders established a great number of mission stations and monasteries. On the Viceroyaltyies' borders, for example in northern Mexico, these also functioned as frontier outposts. In colonial cities schools (colleges) educated also the native population and trained new missionaries.

The missionaries thought of their activity as a conquista spiritual. Their interaction partners were the diverse peoples and ethnic groups of the indigenous population of the Americas who lived at various levels of cultural development: from the Taíno of the Caribbean islands, who Columbus encountered, to the Tupí, Guaraní and Mapuche in South America. At the time of the European discovery of the Americas, in addition to the Indians who lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers, highly organised communities also existed, such as the two ancient American empires, the Aztecs in Mexico with their capital Tenochtitlán, and the Incas in the Andean region of South America with their capitals of Cuzco (Southern Kingdom) and Quito (Northern Kingdom). After brief resistance both empires fell to the Spanish invaders, who were greatly aided by the technological superiority provided for them by fire arms and riding animals, writing, and the wheel – not to forget their more subtle stratagems. But it was by no means merely military confrontation that decimated the Indians, more devastating still were the epidemics caused by the natives' lack of immunity against the diseases that had been brought from Europe. In contrast to the confrontational interaction of the conquistadors and encomenderos (large land owners), the missionaries generally protected the Indians and developed peaceful means of commerce with them.

Among the Europeans different views of the foreign "other" existed side by side: From an ethno-centric perspective, the indigenous peoples were inferior "barbarians"; in another view they were human beings endowed with free will. These positions were reflected in the 16th century debate on colonies between Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda (1490–1573) and Bishop Bartolomé de Las Casas8 in which the majority of the missionaries took the Indians' side and supported legislation that would place them under the protection of the crown. The missionaries who raised the charge of colonial exploitation and made constructive suggestions to end it, inspired the laws that were subsequently passed to protect the Indians (Recopilación de las Leyes de Indias).

In North America the missions began later, and in various different ways. In the 17th century in the French crown colony Nouvelle France – now part of Canada – Catholic missions were sent to such native Indian tribes as the Algonquin, Huron and Iroquois. In the English colonies further south on the East coast the Puritan emigrants also combined colonization and the policy of driving the Indians deeper into the interior with missionary zeal: the latter activity is symbolised in the seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony's which was granted by royal charter in 1628.

In Massachusetts Puritans like John Eliot (1604–1690) founded Christian Indian villages, in Pennsylvania the Quaker William Penn (1644–1718) promoted the peaceful living side by side of Europeans and Indians; successful missionary work was also done in Catholic Maryland by Andrew White (1579–1656) and in Rhode Island by the Baptist Roger Williams (1604–1683) who promoted religious freedom.

New Missionary Movements in the 19th and 20th Centuries

For both internal and external reasons, the Christian mission experienced a decline during the Age of Enlightenment. First, political and cultural changes led to sceptical or negative attitudes towards religion, and in particular to the notion that religion should be propagated; second, the secularisation process brought about the reduction and withdrawal of human and material resources. Still, in the following century the churches experienced a marked upswing which made the 19th century the "century of the mission" (Gustav Warneck (1834–1910)) for Protestantism and Catholicism alike.

The new missionary movement was expressed in the establishment of Protestant missionary societies and Catholic missionary congregations and institutes which meant that new missionary personnel and financial means became available.9 For the German speaking regions we may recall the examples of the Basel Mission, founded in 1815, the Rhenish Mission Society (1828) and the Societas Verbi Divini (1875) of the Steyler Missionaries.

These new missionary institutions were directed towards Asia, Australia and the archipelagos of Oceania,10 but, above all, towards the black continent.11 Not until the 19th century did Europeans explore Africa scientifically and economically, a process in which exploration and missionary work often went hand in hand. This can be seen in the life of the Scotsman David Livingstone (1813–1873), the first European to make an east-west crossing of Africa at the latitude of the Zambezi. Of great influence on the African mission was the almost continuous political division of the continent by European colonial powers, primarily by France and England. The boundaries of partition were fixed at the Congo conference in Berlin (1884/1885). For this reason the Christian missionaries, whose confessions penetrated the continent in parallel actions (the Catholics in a concerted effort, the Protestants less co-ordinated), thought of themselves as cultural pioneers in the sense of colonial politics. Their interaction partners were the numerous people and ethnic groups of Africa, whose countless languages are divided into no less than fifteen major language groups, and whose animist tribal religions found strong competitors in Christianity and Islam – the latter also competing with each other.

Following World War I the problem of mixing missionary work with colonialism faded, but it only finally disappeared in the 1950s and 1960s during decolonization.12 On the Protestant side the great missionary conference in Edinburgh (1910) still reflected a proud consciousness in its own strength and in the kairos of bringing the Gospel to the entire non-Christian world at a rapid pace, but the World Missions conferences after World War I gave up this Euro-centric view (1928) and the division of the world into Christian and non-Christian countries (1947). On the Catholic side the mission encyclical Maximum illud (1919) of Pope Benedict XV (1854–1922) set new accents. It condemned colonialism and nationalism and pleaded for a native clergy in order to better embed the Church in the new territories. Finally, many African novels reflect both the positive and negative aspects of the continent's Christianisation. Examples are Things Fall Apart (1959) by the Nigerian Chinua Achebe (1930–2013) and The Poor Christ of Bomba (Le pauvre Christ de Bomba, 1967) by the Cameroonian novelist Mongo Beti (Alexandre Biyidi-Awala, 1932–2001).

But even if the Christian mission was tied to European colonialism and imperialism, its contribution to the well-being and development of the people should also be acknowledged; for the spread of faith was connected with the care for the whole human being. Thus, as a rule, an integral part of missionary activity included the establishment of an at least elementary system of education and public health: the creation of a "medical mission" and the example of Albert Schweitzer (1875–1965) bear witness to this aspect. With the decline of the Euro-centric view and the demand for ecclesiastical autonomy such important figures as Pope Gregory XVI (1765–1846) and the Anglican Henry Venn (1796–1873) supported the inculturation into the indigenous cultures, their artistic forms and musical traditions. All of these aspects, but also the critique and resistance of the interaction partners, contributed to decolonisation and independence, and laid the foundations for a powerful – quantitative and spiritual – development of Christianity in the sub-Saharan countries. By the 20th century the majority of sub-Saharan Africans were members of a Christian denomination within the framework of Christian pluralism. In this regard it is important to consider the dialectic of mission and colonialism,13 for most of the leaders of African independence movements emerged from mission schools.

Processes of Inter-Cultural Communication and Transfer

From the immense variety of inter-cultural and inter-religious contacts with non-European cultures that took place within the framework of the Christian mission during the five hundred years of the modern era – some contacts sought intentionally, others brought about by accident – we can give only a few examples of the typical forms.

A first type of enduring inter-cultural communication combined political hegemony with cultural mestizaje (ethnic mixing), and decisively shaped Hispano-America und Luso-America. Under the patronage of the Iberian kingdoms, a very active missionary work developed which was sustained by the highly motivated and well-educated members of the spiritual orders, primarily the mendicant ones. Thus, the Franciscans regarded the developing church of Mexico as a new "primordial church" (ecclesia primitiva) that would compensate for the Church's losses in Europe. Like the Dominicans they covered the ancient Aztec empire with monasteries that also acted as mission stations.

Through the immense building activity of churches and monasteries the architectural and artistic forms of the European Renaissance, and later of the Baroque, were transferred to the Americas. This produced hybrid mixtures with the Indian culture and a new type of Christian art14 which can be seen clearly in the American neo-Spanish Baroque or in the indigenous decorative figures

In a second type of inter-cultural communication one can discern the dialectic of the mission. Its positive and its negative aspects have both been recorded in word and picture by the indigenous people. In colonial Peru, at the beginning of the 17th century, the Mestizo Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala (ca. 1550–1615), who was intimately acquainted with the languages, symbols, interpretations and iconographical techniques of communication in both cultures, wrote a dual-language text (Spanish and Quechua). Its almost 1,200 pages, with more than 450 full page pen drawings, offer an illustrated hybrid history that unites Spanish and Inca perspectives. The author had so profoundly taken up the culture and religion of the Europeans that he could also criticize various aspects of colonial society and the Church from within. The comprehensive illustrated chronicle is an iconic narrative of Tahuantinsuyu, the Inca name for the "Land of the Four Quarters", and was conceived by the author as a "letter" to the Spanish King Philip III (1578–1621). As the title, The First New Chronical and Good Government (Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno),15 indicates, it was the king's responsibility to ensure the existence of "good government" according to the principles of justice as the Inca Empire understood them.16

On the one hand the illustrated chronicle describes the history of the Andean peoples and the Europeans up to the time of the conquista, but in such a manner that the Andean cosmological order and periodization are retained (Christ is born during the rule of the second Inca sinchi Roca). Only the middle of the world is altered: Where the centre was Cuzco (=omphalos), there is now the Kingdom of Castile around which the new four regions of the world are arranged. On the other hand, in telling the story of the Spanish involved in colonial domination and the Church mission, it includes severe criticisms; and it also depicts the suffering of the "poor Indian". The copy of the chronicle that is preserved at Copenhagen integrates Peruvian and European history – political, cultural and religious – without neglecting the negative aspects.

In addition to these forms of inter-cultural communication taken from the region of the ancient American empires, other forms emerged in Asia, which were no less communicative, but which were based on a more reciprocal intellectual exchange.

Thus, a third type of intellectual communication can be found in Asia during the 17th and 18th centuries, primarily in the cultures of Japan, China and India. The leading idea in this type of communication is "accommodation" – the attempt to adjust oneself to the specific cultural space and the conditions of the culture one is trying to understand. The foundations for this approach go back to the resourceful Italian Alessandro Valignano who organised missions to the Far East and introduced this paradigmatic change. In view of the highly developed Japanese culture (which was already highly appreciated by Franz Xaver, one of the earliest missionaries) the change consisted in first, not demanding an adjustment to European mores and in avoiding discriminating against the "other" as "barbaric"; even if, conversely, the Japanese called the European "long noses" and "southern barbarians". Second – in recognition of the foreign culture – the new programme called for an immersion into its language and culture, ranging from the sphere of everyday life to official ceremonies.

The basic principle of accommodation, presented in a frequently used manual, (Il cerimoniale per i missionari del Giappone, 1583), is concerned with such themes as language skills and education, clothing and food, politeness and etiquette, and with the adoption of the Zen Buddhist orders of rank by mission personnel. Such a process not only encouraged the reciprocal exchange of ideas and rituals, but also of techniques of printing or painting. The painters of the Kirishitan period – a time when Christianity flourished in Japan and painters were masters of both European and Japanese techniques of iconography – were able to paint "hybrid" pictures, like the portrait of Franz Xaver above. However, at the beginning of the 17th century, the period ended in the persecution and prohibition of Christianity in Japan.

Trans-Cultural Exchange

The change in the missionary paradigm introduced by Valignano did not remain confined to Japan. It was also applied in the great mission project to China; initially by Matteo Ricci who travelled to the Middle Kingdom with the new paradigm in hand. This era of the Christian mission in Imperial China17 was so important, that, even today, in the People's Republic, Ricci is commemorated in Beijing's Zhalan cemetery.

The reciprocal exchange came about because Ricci followed not only the practices of the leading Confucian educational elite, but as a "wise man from the West" (Xitai), also studied the Confucian classics. The prerequisite for this effort was the mastery of spoken and written Chinese, but also the friendship and intellectual exchange that the missionaries cultivated with Chinese scholars. Some of the latter, such as Xu Guangqi (1562–1633) and Li Zhizao (1569–1630), converted to Christianity and became "pillars" of cultural exchange and of the early Church in China.

Ricci's missionary concept viewed the members of the Confucian educational elite as dialogue partners. He wished to convince them that Christian doctrine not only harmonised with the best Chinese traditions, but indeed fulfilled their promise. Beyond an accommodation regarding external aspects, Ricci also pursued an inter-cultural relationship that made scientific exchange and intellectual dialogue possible. The concept that was so successfully applied by the great missionaries to China in the 17th and 18th centuries (such as Ricci, Adam Schall von Bell, Martino Martini [1614–1661], Ferdinand Verbiest and others) also included a policy of adapting to Chinese culture in an approach "from above". On the part of the European scientific and political elite this meant openness to Chinese values, acceptance of ancestor worship as a civil rite, and the indirect propagation of faith through science, technology and the arts. Through his extensive correspondence with the Catholic missionaries in China, the Protestant scholar Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz promoted exchange and the transfer of knowledge and was particular interested in the "propagatio fidei per scientias".18

Within the framework of the mission in China, not only did European knowledge, technology and art reach the Middle Kingdom, but information and knowledge about China also flowed back to Europe. This took place in extensive missionary reports, in correspondence like that with Leibniz, through systematic presentations of history and culture (Nicolas Trigault [1577–1628], Martino Martini), and through such illustrated works as China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae & artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata (1667) by Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680)[

Of particular importance was the analysis of Chinese wisdom and culture undertaken, among others, by the Italian missionary Prospero Intorcetta (1625–1696). His book, Sinarum scientia politico-moralis, published in 1669, made the life and thought of Confucius (551–479 B.C.) accessible to the West for the first time. With the Belgian Philippe Couplet (1623–1693) he published Confucius Sinarum Philosophus, sive scientia sinensis (Paris, 1687), the first Latin translation of the classical Confucian writings which are the heart of Chinese culture. These and other publications awakened European interest in the wisdom and culture of China and laid the groundwork for modern sinology.

"Translations"

Inter-cultural communication, and therewith missionary communication, is based on language. Therefore it requires "translations", for oral exchanges, for literal or paraphrasing interpretations of texts, but also for the different cultural forms in which practical life, ethics and art are expressed. One of the most important examples in this regard is the transfer of religious knowledge through the translation of the Bible as the basic document of Christian faith. It is one of the fundamental convictions of Christianity that the Bible can be translated into all languages, that all languages are capable of expressing the Gospel, the written form of the "good news". This conviction is expressed theologically in the events of the Pentecost and the depiction of their universal comprehensibility (cf. Acts 2:11). The very fact that the New Testament texts were not written in Aramaic, the language of Jesus, but in the lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean, reveals the will to translate, and demonstrates Christianity's translatability and capacity for inculturation. The "Holy Bible" was indeed written in Hebrew and Greek, but not so tied to these languages that it cannot be translated. This fact is demonstrated by the many efforts to translate it, beginning with the Latin version (Vulgata) and continuing through numerous translations in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, and in paraphrases in European and non-European vernaculars, such as Gothic, English, Slavic, Franconian, Coptic, Armenian, Persian and Arabic.

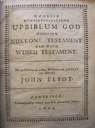

For the missionary work of the modern era translations of the Bible and other Christian writings, such as catechisms, into non-European languages gained increasing importance and, since the invention of printing with moveable type, there existed an incomparably more efficient means of spreading the message. The Catholic missions of the early modern period produced complete translations of the New Testament, partial translations of the Bible for liturgical purposes, paraphrases and pictorial presentations of Biblical pericopes, as well as Gospel harmonies and the transformation of Biblical motives into literary epics. Typical of these efforts are the illustrated Chinese Gospel harmony (1635) of Giulio Aleni (1582–1649) or the Bible epic in verse written for the Indian cultural area by Thomas Stephens (1549–1619) in Marathi (ca. 1600). Whereas Bible translations in the age of confessionalization were treated by Catholics in a more restricted manner, or indeed were forbidden by the Church or the state, the Protestant Bible translations for missionary purposes reached new heights. John Eliot, an English Puritan living in New England, printed the New World's first complete Bible. He had written a grammar of Algonquin (Massachusetts) and, in 1663, published a translation of the entire Bible in Algonquin under the title of Mamusse wunneetu-panatamwe Up-Biblum God in Cambridge (Massachusetts).

In Asia, several decades later, the German missionary, Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg, who was sent by the Danish and English Halle mission to Tranquebar in southern India, produced a translation of the New Testament in Tamil (1715); at the beginning of the 19th century the English Baptist William Carey (1761–1734) who was active as a linguist, translated the Bible into a number of Indian languages, including Bengali, Sanskrit und Marathi – in 1801 a Bengali New Testament was printed at Serampore.

In Africa there were early Bible translations into Coptic, Ethiopian and Nubian. But since, with a few exceptions, the African missionary activity of both confessions did not begin until the 19th century, Bible translations came late to the extraordinarily diverse linguistic landscape of the sub-Sahara. In this regard it is important to bear in mind that the pre-requisites for such a translation are a transcription and linguistic analysis of the language into which the translation is to be made, and an at least rudimentary literacy among the people for whom the translation is intended. Thus, on both the giving and receiving side, the transmission of the Biblical message involved complex processes of learning, which also became culturally and socially effective beyond the purpose of the mission itself.

Due to the Christian mission's global enterprise of translation the Bible has probably become the world's most translated book.19 In 1800 there were a mere 80 Bible translations, but in the last two centuries the number rose dramatically, primarily due to the efforts of missionary and Bible societies; by 1900 the number of translations world-wide had risen to 620.

Outlook

To sum up, one may distinguish between two major phases of the Christian mission in the modern era. First, the global mission that began at the threshold to the modern era and extended to the Age of Enlightenment and secularization around 1800; the second phase began in the 19th century and extended into the first half of the 20th, and renewed the global mission. The first phase took place generally within the framework of European expansion and its colonial and hegemonic aspirations. It happed primarily under the patronage of the (Catholic) Iberian maritime powers and the religious orders whose humanistic education influenced (and was influenced) by it. The second phase took also place under the auspices of colonialism – now of the new (Protestant) European maritime powers – but was mainly borne by the new religious initiatives of the denominations, especially by those of the revival movements. In both phases critical voices called for the de-politicisation of the mission and for religious autonomy. And in both phases colonialism played an ambivalent role in its combination of nation-state and religion. On the one hand, it provided support for the mission of Christianisation, but on the other it was a burden that was not overcome until the second half of the 20th century during the process of decolonisation. Still, both phases were also characterized by the selfless efforts of highly motivated missionaries who sought to plant the seeds of Christianity in other cultures and who, in various ways, promoted inter-cultural exchanges, principally in the areas of linguistics and sacred art.

The transition between the two phases at the end of the 18th century marked a crisis in the missionary work. This was due, not merely to the decline of the powers under whose patronage missionary activity had first taken place, but also to the process of secularization that found expression in the suppression of the Society of Jesus, the French Revolution, the Principal Recess of the Imperial Deputation of Ratisbon, and in various intellectual currents. For the missionary activities of the various denominations, however, this had the salutatory effect of purifying motives. It marked the start of the last phase of missionary activity, shaped by both Europe and North America, which came to an end in the middle of the 20th century. After decolonisation Christian missionary activity took on new and varied forms, and today it goes forth from all continents.