Introduction

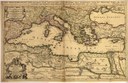

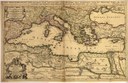

Just where Europe ends in the south is unclear. In the 21st century, the EU "protects" its border not only in the Mediterranean and the Balkans, but also south of the Sahara to prevent the immigration of people from Africa and Asia. At the same time, since the 18th century the Occident has been repeatedly located north of the Pyrenees, Alps, or the Balkans in order to exclude Southern Europe. The most recent example is the debate about the so-called PIGS states in the context of the financial crisis of 2008.1 This shifting of the European southern border is consequently by no means new. Rather, religions and cultures, empires and populations in the Mediterranean have repeatedly shifted in different directions since ancient times. Since sea transport was faster than land transport, the Mediterranean served as a bridge for trade, conquest and settlement – first in the context of the Phoenician and Greek colonizations, then above all in the imperial period of the Imperium Romanum, which claimed the Mediterranean as mare nostrum. Even after the end of the Pax Romana, the Mediterraneum remained a space of condensed communication in which people, objects, and ideas circulated, even during the Germanic migration, the Arab-Muslim expansion, or the Christian crusades. Long before the modern era, the Mediterranean enabled transcontinental relations, transfers, and interactions.2

The Mediterraneum is therefore regarded as a paradigm of a maritime interaction space from which global-historical ocean studies is currently struggling to emancipate itself.3 Furthermore, the region can be understood as a laboratory of later modern globalization, in which "European" and "non-European" elements already collided before 1492 and mixed.4 A well-known outcome of these cultural transfers was the Mediterranean flora: Apart from wheat, olive trees, and wine, the flora, now considered typically "Mediterranean," is the result of cultural transfers from other world regions. The cypress came from Persia, the eggplant from India. The citrus fruits from the Far East were brought here by Arabs. Agaves, peppers, and tomatoes reached the Mediterranean Sea from the so-called "New World" in the course of the Columbian Exchange.5 The World Cultural Heritage Site of the Mediterranean Diet, which today is regarded by Western elites as the ideal of healthy eating and – according to UNESCO – should therefore remain as unaltered as possible, was itself a result of the appropriation of global imports.6

At the same time, and in contradiction to these diverse mixtures, cross-cultural encounters and conflicts in the modern Mediterranean area also produced powerful demarcations of Europe. These include the thesis of the Belgian historian Henri Pirenne (1862–1935), who interpreted the Arab-Muslim expansion as the destruction of Mediterranean unity and the birth of a "European Middle Ages,” or Eurocentric and postcolonial master narratives such as The West and the Rest and Orientalism. Despite conflicting strategic aims, these narratives unanimously understood the Occident and Islam/Orient as monolithic blocks and dichotomized them. At the same time, they ignored both the intensive relations and the heterogeneity and internal asymmetries of the respective regions.7 Europe's borders in the Mediterranean area have thus at once become more fluid and more fixed.

Spatial borders

Historically, Mediterranean studies are one of the oldest area studies. Knowledge about the sea, its coasts and islands has been collected since ancient times.8 Geographically, the Mediterraneum is now considered a spatial unity because "tectonics and relief development, soil formation and vegetation cover, the subtropical alternating humid climate and the Mediterranean as a marine ecosystem have created similar physical-geographical structures in all zones." Moreover, the region’s internal contrasts are emphasized: "The spatial contrasts in the Mediterranean region are more dominant than all existing uniform structures."9

The external borders are oceans and seas such as the Atlantic, the Red and the Black Seas, mountain ranges such as the Alps, the Dinarides and the Rhodopes, the Pontic Mountains, the Taurus and Lebanon, and the Atlas and the Rif. Deserts such as the Sahara and the Syrian Desert are not counted as part of the region, although the Libyan Desert borders the Mediterranean, which conflicts with overly narrow climatic or geological definitions. The most important inner geological boundary is the seismically highly active Strait of Sicily, where the African and Eurasian plates meet. It divides the Mediterranean into a western and an eastern basin – a distinction which, as we will see, also plays an important role in historical research. Due to its internal fragmentation, the Mediterraneum is considered a “sea complex,” narrowed by islands, divided by peninsulas, enclosed by rugged coasts. 10 To the west, we distinguish the Alborán and Balearic Seas, the Gulf of Lion, the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian Seas; to the east, the Libyan, Adriatic and Ionian Seas, the Aegean and Levantine Seas, and the Sea of Marmara. The terrestrial parts of the region are also considered heterogeneous, partly because peninsulas, coasts, and islands offer different natural conditions, and partly because these areas have been exposed to various human influences in the past.11

10 To the west, we distinguish the Alborán and Balearic Seas, the Gulf of Lion, the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian Seas; to the east, the Libyan, Adriatic and Ionian Seas, the Aegean and Levantine Seas, and the Sea of Marmara. The terrestrial parts of the region are also considered heterogeneous, partly because peninsulas, coasts, and islands offer different natural conditions, and partly because these areas have been exposed to various human influences in the past.11

Despite the fragmentation of the region, the two most influential works on the history of the Mediterranean unanimously emphasize its unity, continuity, and uniqueness, ascribing to precisely this geography a constitutive role. In La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l'époque de Philippe II (1949/1966 ), which is considered the foundational document of historical Mediterranean research, Fernand Braudel (1902–1985) underscored the importance of the physical space for Mediterranean history. Primarily using the 16th century as an example, he carried out a revolutionary tripartite division of historical time into a geographical, social, and individual time. In his three-tiered model, nature on the one hand, economy and society, culture and politics on the other, have a strict hierarchy. The basis of all processes and structures, decisions and actions is the natural environment of the human being, whereas a reverse influence hardly seems possible. One leitmotif of the book is therefore the human struggle with nature. While sailing, for example, is made difficult or prevented by weather-related winter breaks, dangerous ocean currents, and unpredictable winds, the expansion of the "cultural frontier" on land devours immense resources and requires constant effort and care. The key concepts of this proposal for a histoire totale of the early modern Mediterranean are géohistoire and longue durée.12

No less ambitious is the approach of the medievalist Peregrine Horden (b. 1955) and the ancient historian Nicholas Purcell. Following Braudel, but extending far beyond his efforts from a temporal standpoint, they demonstrate the unity, continuity, and uniqueness of the region for the entire pre-modern period, from prehistory to early modern times. In The Corrupting Sea (2000), the Mediterranean region appears more fragmented: as a disjointed ensemble of micro-regions that developed ecological and socio-cultural niches and were dependent on adaptation and exchange in the face of many different unknowns. The explanatory model, which aims to establish the singularity of the Mediterranean world, rests on connectivity as a risk management tool to overcome fragmentation and ban the dangers of a "corrupting sea." Although the work has been heavily criticized, it has given new impetus to Mediterranean Studies and has had a decisive influence on new Mediterranean studies.13

Recent research is highly specialized and fragmented.14 While early modern studies sometimes focus on extensive (trans-)Mediterranean relations and dynamics, works on modernity usually focus on Mediterranean subregions (South Eastern Europe15, Maghreb, Middle East),16 empires, port cities17 or islands18 – or on the numerous nation-states that have existed since the 19th century in the region, first north, then south of the sea. Partial seas such as the Adriatic Sea and Levant have also already been investigated as "historical regions."19 Recently, more focus has also been placed on straits and canals.20

have also already been investigated as "historical regions."19 Recently, more focus has also been placed on straits and canals.20

Epochal thresholds

The epochal dimensions of the Mediterranean paradigm are disputed, however. The cited classics draw a sharp contrast between the early and the late modern era: In the transition between the two epochs, Braudel sees the Mediterranean shrinking "on a human scale" and the primacy of nature over man dwindling. In the 16th century, it was "much mightier" “than today.” It had yet to become "the ‘inland lake’ of the 20th century, home of tourists and yachts for whom the mainland is always within reach, a lake along whose shores the Orient Express passed by without even stopping yesterday.” New possibilities of manipulating the space were added to those of traversing it more quickly: Malaria-contaminated plains such as the Mitidja and Thessaloniki plains, the Pontine Marshes and the Ebro Delta were "permanently" developed in the 20th century. Brought "under the control of man", they became agriculturally exploitable.21 Braudel highlighted these modern examples of the taming of nature to emphasize the contrast with pre-modernity. However, as his geohistorical approach was understood as transcending epochs, it reinforced the impression of a static Mediterranean world.22 This was also due to Braudel's thesis of an economic "decline" of the Mediterranean, according to which the economic dynamics after the 16th century migrated, in a manner resembling Hegel’s (1770–1831)[ ]world spirit, to the Atlantic.23

]world spirit, to the Atlantic.23

The contrast between pre-modernity and modernity is even sharper in Horden and Purcell. They assume that the Mediterranean unity and continuity since the 19th century (sometimes 1800 serves as a caesura, sometimes 1900) was destroyed, so that a coherent history of the region was no longer possible afterwards.24 Following this, the “waning” or “vanishing” of the Mediterranean region has become a topos in English-speaking research, which makes pairs of terms such as Mediterranean modernity or modern Mediterranean appear as oxymorons.25

One argument against this exclusion of modernity from Mediterranean history is that criteria such as unity, continuity, or singularity can hardly be regarded today as yardsticks for the historiographical identity of a region. This is not so much because they themselves are of imperial provenance, but rather because the pre-modern Mediterranean region was also characterized by diversity and discontinuity and showed similarities to other “Mediterraneans,” making it appear by no means unique, but comparable.26 On the other hand, the connectivity of the region did not decrease one bit in the 19th century. Rather, the Mediterranean coasts, hinterlands, and islands have become more closely interwoven than ever before through new media of transport and communication. Steam navigation not only accelerated the crossing of the sea and made it precisely calculable; it also changed the way we perceive it. Thus on maps and in travel guides the Mediterranean shrank from ocean to sea.27

In the age of the "Anthropocene,"28 there were also epochal upheavals on land: The industrialization of agriculture and viticulture, the proletarianization and urbanization of the rural population, the mass recruitment and emigration of workers and soldiers,29 the exodus of the islands30 the emergence of mega cities,31 and the systematic development of the region through tourism32 changed the natural and cultural space so comprehensively that indeed the concept of continuity cannot be applied here.

The exclusion of the region from the master narratives of modernization theory, which the social sciences performed after the decolonization in the geopolitical context of the Cold War,33 led to the fact that the Mediterranean region, despite these dynamics, is still today considered a passive object – or even a victim – of exogenous factors of modern change. What is often overlooked is that many of these projects were driven by Mediterranean actors themselves and that the region itself produced numerous innovations that had an impact far beyond it. This applies to the cultivation and processing of plant products, which – for example in the vineyards of the Languedoc-Roussillon or in the steam-driven Marseilles oil plant factories and Egyptian grain mills – were industrialized early on. It is equally true for tourism, which was known in the early modern period as the Grand Tour; it was invented the south of Europe and perfected after 1950 in the entire Mediterranean region. It also holds for politics and religion: The Corsican Constitution of 1755 was the first written constitution in the world and was celebrated by the European Enlightenment as a milestone of progress.34 Constitutional liberalism celebrated its first successes on the Iberian Peninsula.35 Egyptian, Greek, Italian, and Syrian radicals from Levantine port cities established global networks between Latin America and South Asia.36 And while Ultramontanism focused global Catholicism more on the Pope and the Roman Curia and thus drove worldwide the centralization of the Church,37 Pan-Islamism had already emerged in Cairo.38 In the 20th century, not only were fascism and the mafia being globally imitated and imported phenomena, but so were specific forms of preparing pasta or coffee.39 Thus, in the modern age, there was not only a global penetration of the Mediterranean area,40 but there was also a partial Mediterraneanization of the world.

In light of this, it seems reasonable to not allow the history of the Mediterranean region to end with the pre-modern era. Instead, the modern age must also ask about interactions, convergences and divergences, transfers and interactions, as well as about relations to, similarities with and differences from other regions of the world.41 Rather than hard epochal boundaries, it is necessary to apply soft epochal thresholds – fluid transitional periods that can be dated differently depending on the subject in question.42

The Ottoman Mediterranean Sea

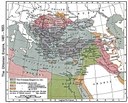

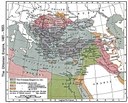

Empires were a structural principle of the early modern Mediterranean region. Besides Spanish Habsburg,43 the largest was the Ottoman Empire. In 1683, when it was at the zenith of its territorial expansion and had besieged Vienna for a second time, Ottoman rule stretched from the Rif to the Caspian Sea, and from today's Ukraine to the Gulf of Aden. The Ottoman expulsion of the Mamlukes from Syria and Egypt (1516/17) brought the banks of the Levant under an imperial regime for the first time in a thousand years. From then on, the Ottomans not only reigned over the Hejaz with its holy Islamic sites Medina and Mecca but also, after the conquest of Baghdad (1534), Aden (1538) and Basra (1549), they controlled the isthmus to the Red Sea and the caravan routes to the Persian Gulf, which were central to trade with India. They used these connections to establish extensive trade networks in Asia. In this respect, the partial redirection of European forces towards the Atlantic Ocean in the 16th century did not mark the end of Mediterranean history, but rather the activation of other transregional contacts.44

for a second time, Ottoman rule stretched from the Rif to the Caspian Sea, and from today's Ukraine to the Gulf of Aden. The Ottoman expulsion of the Mamlukes from Syria and Egypt (1516/17) brought the banks of the Levant under an imperial regime for the first time in a thousand years. From then on, the Ottomans not only reigned over the Hejaz with its holy Islamic sites Medina and Mecca but also, after the conquest of Baghdad (1534), Aden (1538) and Basra (1549), they controlled the isthmus to the Red Sea and the caravan routes to the Persian Gulf, which were central to trade with India. They used these connections to establish extensive trade networks in Asia. In this respect, the partial redirection of European forces towards the Atlantic Ocean in the 16th century did not mark the end of Mediterranean history, but rather the activation of other transregional contacts.44

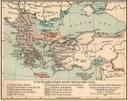

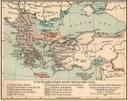

The Ottoman expansion began in the 14th century with the annexation of the former Byzantine provinces

began in the 14th century with the annexation of the former Byzantine provinces . After the repulsion of the Mongolians, who under Timur Lenk (1336–1405) had advanced all the way to Anatolia, the Ottomans conquered the "second Rome" Constantinople in 1453

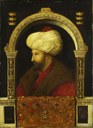

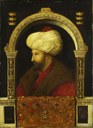

. After the repulsion of the Mongolians, who under Timur Lenk (1336–1405) had advanced all the way to Anatolia, the Ottomans conquered the "second Rome" Constantinople in 1453 . This event still marks the beginning of modern times in Turkish historiography.45 By adopting the titles of the Byzantine emperors Mehmed II (1432–1481)[

. This event still marks the beginning of modern times in Turkish historiography.45 By adopting the titles of the Byzantine emperors Mehmed II (1432–1481)[ ] signaled his intention to restore the Roman Empire. As a consequence, the Ottomans also set their sights on the West. In 1481, they conquered the Apulian Otranto, where they could only be pushed back by a broad alliance of Christian powers.46 The Spanish Reconquista

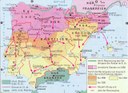

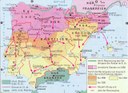

] signaled his intention to restore the Roman Empire. As a consequence, the Ottomans also set their sights on the West. In 1481, they conquered the Apulian Otranto, where they could only be pushed back by a broad alliance of Christian powers.46 The Spanish Reconquista eventually drew them westward nevertheless: After Spain's Christian kingdoms had declared war on the Emirate of Granada in 1482, the Nazarites called on the Ottomans for help. Under the command of the former privateer Kemâl Reis (1440–1511), an Ottoman fleet intervened in Malaga and brought Muslim refugees to North Africa without preventing the fall of the last bastion of Al-Andalus (711–1492).47

eventually drew them westward nevertheless: After Spain's Christian kingdoms had declared war on the Emirate of Granada in 1482, the Nazarites called on the Ottomans for help. Under the command of the former privateer Kemâl Reis (1440–1511), an Ottoman fleet intervened in Malaga and brought Muslim refugees to North Africa without preventing the fall of the last bastion of Al-Andalus (711–1492).47

Andrew Hess has interpreted the year 1492 as a watershed in Mediterranean history. In view of three epochal events – the fall of Granada, the expulsion of the Jews from Spain decreed in the Alhambra Edict, and the discovery of America by Columbus (1451–1506) – a cleavage of the Mediterranean region took place over the long term. Christians and Muslims had turned away from each other. As a result, the Strait of Gibraltar went from being a bridge of exchange and the intermingling of cultures and religions to a hard boundary of clashing civilizations.48 This thesis must be qualified in several respects. First of all, the Reconquista enabled the Ottomans to expand their geographic knowledge of the West. On his military expeditions, Kemâl was accompanied by his nephew Pîrî Reis (ca. 1470–1554)[ ]. The latter drew a nautical chart of the central Atlantic in 1513 and wrote a "Book of the Seas" (Kitab-ı Bahriye) in 1521, which contains hundreds of topographic maps of the coasts, bays, islands, and tributaries of the Mediterranean as well as detailed information on Mediterranean cities, regions, and countries. It is thus considered the beginning of modern Mediterranean cartography.49 Subsequently, the Ottomans expanded not only in Central Europe (1521–1566 Hungary) and in the Levant but also in North Africa in order to halt the Spanish (Ceuta/Melilla since 1415/1497, Oran 1509–1732) and the Portuguese (Tangier 1471–1661). In 1519, Algiers, which was under the control of the Muslim pirate Hayreddin Paşa Barbaros ("Barbarossa," ca. 1465–1546) requested the Sultan's help and became an Ottoman vassal state. Barka (1521), Tripoli (1551) and Tunis (1531/74) later followed suit. When the Ottomans surprisingly lost the bulk of their fleet and navy in 1571 in the naval battle of Lepanto

]. The latter drew a nautical chart of the central Atlantic in 1513 and wrote a "Book of the Seas" (Kitab-ı Bahriye) in 1521, which contains hundreds of topographic maps of the coasts, bays, islands, and tributaries of the Mediterranean as well as detailed information on Mediterranean cities, regions, and countries. It is thus considered the beginning of modern Mediterranean cartography.49 Subsequently, the Ottomans expanded not only in Central Europe (1521–1566 Hungary) and in the Levant but also in North Africa in order to halt the Spanish (Ceuta/Melilla since 1415/1497, Oran 1509–1732) and the Portuguese (Tangier 1471–1661). In 1519, Algiers, which was under the control of the Muslim pirate Hayreddin Paşa Barbaros ("Barbarossa," ca. 1465–1546) requested the Sultan's help and became an Ottoman vassal state. Barka (1521), Tripoli (1551) and Tunis (1531/74) later followed suit. When the Ottomans surprisingly lost the bulk of their fleet and navy in 1571 in the naval battle of Lepanto against a "Holy Alliance" organized by Pope Pius V (1504–1572) and led by the Habsburgs, their advance westward was stopped. Still they did not "retreat" by any means from the Mediterranean after 1571. Rather, the Levantine Sea remained the undisputed center of their empire. The Sultan ruled over the territory in the 18th century, as the British and French were fighting here. This contrasted with European conceptions of maritime law, which regarded the sea 15 kilometers away from the coast as unprotected. Even beyond the Levant, the Ottomans remained a peacekeeping power in the Mediterranean. When the Venetians wanted to negotiate with the pirates and slave traders of the North African barbarian states

against a "Holy Alliance" organized by Pope Pius V (1504–1572) and led by the Habsburgs, their advance westward was stopped. Still they did not "retreat" by any means from the Mediterranean after 1571. Rather, the Levantine Sea remained the undisputed center of their empire. The Sultan ruled over the territory in the 18th century, as the British and French were fighting here. This contrasted with European conceptions of maritime law, which regarded the sea 15 kilometers away from the coast as unprotected. Even beyond the Levant, the Ottomans remained a peacekeeping power in the Mediterranean. When the Venetians wanted to negotiate with the pirates and slave traders of the North African barbarian states , they called a mufti. Since the Ottoman legal order spanned the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean, Christians and Jews turned to Ottoman institutions in many places. The Ottoman-dominated Levant was not determined alone by the Christian-Muslim dichotomy, as the Venetian-Ottoman wars suggest. Rather, Muslims, Latin and Orthodox Christians lived here together uninterrupted. The Ottoman Levantine trade with Venetians and French, British and Dutch, whose financial volume around 1700 was only slightly less than that of Spanish trade with America, provided for exchange and communication between Christians, Jews, and Muslims. In this respect, the theory that 1492 represented a Mediterranean break with civilization needs to be put into perspective.50

, they called a mufti. Since the Ottoman legal order spanned the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean, Christians and Jews turned to Ottoman institutions in many places. The Ottoman-dominated Levant was not determined alone by the Christian-Muslim dichotomy, as the Venetian-Ottoman wars suggest. Rather, Muslims, Latin and Orthodox Christians lived here together uninterrupted. The Ottoman Levantine trade with Venetians and French, British and Dutch, whose financial volume around 1700 was only slightly less than that of Spanish trade with America, provided for exchange and communication between Christians, Jews, and Muslims. In this respect, the theory that 1492 represented a Mediterranean break with civilization needs to be put into perspective.50

Nevertheless, the Reconquista marked a profound turning point. For its part, Christian Spain had changed the question of the "purity of faith" into a question of the "purity of blood" (limpieza de sangre). Here, they expelled forcibly converted Jews (marranos) and Muslims (moriscos) and, in the process, ushered in modern racism. By contrast, the Ottomans, whose dynasty consisted of the marriage of Ottoman men with noble Greek and Serbian women of Christian faith, integrated both the Muslims and the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula.51 Their inclusion led to a partial "Westernization" of the population and the culture of Ottoman cities. Some joined the corsairs of the North African Barbary states, who specialized in privateering wars and land raids in order to earn ransom and protection money by enslaving and selling Christians.52 The integration of the fugitives and displaced persons was by no means without its problems. On the contrary, violent conflicts arose between "Andalusians," "Turks," the kûlughli (“slave sons”; the offspring of the liaisons between the latter and native women), and the locals.53 Nevertheless, the integration of the Sephardi Jews illustrates the Ottoman Empire's creative approach to religious difference. Following a medieval Islamic principle of protection (dhimma), members of other book religions (ahl al-kitab) were allowed to practice their faith here largely autonomously. They had to pay special taxes and perform duties; they were also generally denied higher administrative offices (Greek Orthodox in the Balkans and converts were not subject to these restrictions). Still, they could participate in decision-making processes and civil life at the local level. This toleration of religious otherness originated in the early phase of the empire, when the Ottomans still ruled by a majority over Christians. It also followed an economic calculation, as the extensive trading networks of Armenians, Greeks, and Jews spurred the imperial economy. They were not legally privileged until the 16th century, when Muslims again formed the majority. Although there were now isolated Islamization campaigns, forced conversions did not take place, and also pogroms were, unlike in Christian-ruled Europe, "the absolute exception."54

This flexible system of handling cultural and religious diversity, which has recently been defined as "Ottoman cosmopolitanism" in an Empire of Difference55 was under increasing pressure in the 19th century. In the uprisings and secessions of the Serbs (1804–1878) and Greeks (1821–30) modern nationalism gave an early indication of its explosive power.56 Under the influence of Western European powers, a progressive bureaucracy in the Sultan's palace in the years from 1839–1876 pushed through a "reorganization" (Tanzimât) of the Ottoman Empire. As a result, religious minorities were given equal rights and the Ottoman markets were opened up, which turned the Levant into an testing ground for free-trade imperialism.57

While in late Ottoman port cities, new forms of consumption, sociability, and mixing of cultures emerged, which were understood as "cosmopolitan,"58 the "long" First World War, which began in 1911 with the Italian attack on Tripoli and ended in 1923 with the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, led to savage massacres of Christians and Muslims in the Balkan wars from 1912/13 , to the genocide of the Armenians in 1915/16 and, in the Greek-Turkish population exchange in 1923, to the first contractually regulated and state-organized forced relocations ("ethnic cleansing") in world history. In a tragic historical irony, Smyrna (turk. Izmir), which was considered a model of late Ottoman cosmopolitanism, became an epicenter of interreligious nationalist violence in 1922.59 In the testing and establishing of new forms of violence, the Mediterranean region must also be considered a laboratory of the modern age.60

, to the genocide of the Armenians in 1915/16 and, in the Greek-Turkish population exchange in 1923, to the first contractually regulated and state-organized forced relocations ("ethnic cleansing") in world history. In a tragic historical irony, Smyrna (turk. Izmir), which was considered a model of late Ottoman cosmopolitanism, became an epicenter of interreligious nationalist violence in 1922.59 In the testing and establishing of new forms of violence, the Mediterranean region must also be considered a laboratory of the modern age.60

Mare Nostrum

Between the 19th and the middle of the 20th century, Europe's political, geographical, demographic and cultural borders were shifted to the south and east. As a result, from a European perspective, the Mediterranean appeared as a mare nostrum.61 The Mediterranean islands were also Europeanized. If they were previously classified as belonging to the African or Asian continent, they have since been classified as belonging to Europe. This is also the case with Malta, Lampedusa and Pantelleria, Lesbos, Rhodes or Cyprus, which lie directly off the coast of Africa or Asia.62

Imperial competition had already intensified in the 18th century. In the north, the Habsburgs63 and Romanovs stepped up the pressure on the Ottomans. In the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), Russia acquired the Sea of Azov and the Crimea and free access to the Black Sea and to the Mediterranean Sea. The Orthodox Christians of the Ottoman Empire were henceforth under the protection of the tsars, which nourished desires for a change of imperial rule or even autonomy.64 In the 19th century, the model of “protecting” religious "minorities" was then also adopted in Western Europe. France, in particular, was seen as the protecting power of the Latin Christians, while the private Alliance Israélite Universelle was responsible for the emancipation of the Jews in North Africa and the Near East. This further undermined the authority of the Sultan, whom European caricaturists have mocked since the Crimean War (1853–1856) as the "sick man on the Bosporus." 65

65

Ottoman power also eroded in the West. Already in the 18th century, the North African Barbary states had become independent and had concluded their own treaties with European powers, which in turn protected themselves from capture. After 1800, this arrangement became invalid: Now, the USA conducted a war against Tripoli (1801–1805) and bombed Algiers (1815); the British and Dutch followed their example shortly thereafter (1816). The French blockade and conquest of Algiers (1827–1830) finally marked the end of Barbary rule over the western Mediterranean.66 Already before that, France and Great Britain had occupied strategically important straits (Gibraltar 1713 brit.) and islands (Minorca 1708/63 brit., Corsica 1768 fr.). The loss of their most important colonies in America (USA 1776, Saint-Domingue) additionally drew the attention of both powers to the Mediterranean area, especially to the Isthmus of Suez as the gateway to India, which was considered the key to world domination.

In order to launch a new offensive in India, French troops occupied Egypt under Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) from 1798–1801. Although the campaign failed militarily, it had far-reaching consequences. The Egyptian scholar Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti (1754–1822) recognized in it the "beginning of a series of great strokes of fate" for the Islamic world.67 He was certainly impressed by the curiosity of the scholars accompanying the expedition for Ancient Egypt. Their research led to the monumental Déscription de l'Égypte (1809–29)

under Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) from 1798–1801. Although the campaign failed militarily, it had far-reaching consequences. The Egyptian scholar Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti (1754–1822) recognized in it the "beginning of a series of great strokes of fate" for the Islamic world.67 He was certainly impressed by the curiosity of the scholars accompanying the expedition for Ancient Egypt. Their research led to the monumental Déscription de l'Égypte (1809–29) , which founded modern Egyptology. With a view to the present and the future, however, Napoleonic propaganda conveyed the idea of a civilizing superiority of the Occident, which obliged it to liberate the Orient from supposed "backwardness” and to put it on the track of progress. This Orientalist narrative has been used again and again since then to justify Western interventions in the Near and Middle East.68

, which founded modern Egyptology. With a view to the present and the future, however, Napoleonic propaganda conveyed the idea of a civilizing superiority of the Occident, which obliged it to liberate the Orient from supposed "backwardness” and to put it on the track of progress. This Orientalist narrative has been used again and again since then to justify Western interventions in the Near and Middle East.68

In the 19th century, the British-French scramble for the Mediterranean intensified. While the British occupied strategically important islands and canals with Malta (1814–1964), the Ionian Islands (1815–64), Cyprus (1878–1960) and indirect rule over Egypt (1882–1922),69 the French in the Maghreb (Algeria 1830–1962, Tunisia 1881–56, Morocco 1912–56) built a terrestrial empire. Before the First World War, along with Italy in Libya (1911–51) and Spain in northern Morocco (1912–56), two further European colonial powers landed on the southern Mediterranean shore.70 In 1916, France and Great Britain agreed in the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement on the future division of the West Asian provinces of the Ottoman Empire. In 1917, the Balfour Declaration

on the future division of the West Asian provinces of the Ottoman Empire. In 1917, the Balfour Declaration for the creation of a national home for Jewish people in Palestine laid the groundwork for the "Middle East conflict." After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, during the interwar period France and Great Britain took over the League of Nations mandates

for the creation of a national home for Jewish people in Palestine laid the groundwork for the "Middle East conflict." After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, during the interwar period France and Great Britain took over the League of Nations mandates for Palestine and Transjordan (brit.), Syria, and Lebanon (fr.). The entire Mediterranean region thus stood under the influence of European powers,71 even if this was already challenged by anti-colonial movements as in the Egyptian revolt of 191972 or the Rif War (1922–26).73

for Palestine and Transjordan (brit.), Syria, and Lebanon (fr.). The entire Mediterranean region thus stood under the influence of European powers,71 even if this was already challenged by anti-colonial movements as in the Egyptian revolt of 191972 or the Rif War (1922–26).73

In the course of this imperial expansion of Europe to the south, the idea emerged of a "Mediterranean region" as a unified natural and cultural area. As shown by the example of the French spatial concept of the Méditerranée, botanists, geologists, anthropologists, archaeologists, philosophers, and historians all actively contributed to this concept.74 While anthropological knowledge was used to dominate the indigenous peoples, the archaeological excavation of monumental pasts of Mediterranean antiquity served to justify imperial dominance and hegemony. By presenting themselves as legitimate heirs of ancient Egypt, Greece or Rome in the metropolitan centers well as the peripheries of their empires, European powers effectively restored the Mediterranean unity and continuity allegedly destroyed by Islam. The Mediterranean region was thus conceived as the cradle of a civilization that was both universalistic and Eurocentric. The centuries of Muslim rule, on the other hand, were regarded as siècles obscures.75

or Rome in the metropolitan centers well as the peripheries of their empires, European powers effectively restored the Mediterranean unity and continuity allegedly destroyed by Islam. The Mediterranean region was thus conceived as the cradle of a civilization that was both universalistic and Eurocentric. The centuries of Muslim rule, on the other hand, were regarded as siècles obscures.75

In the interwar period, European politicians, geographers, and engineers of different world views and provenance then even imagined a fusion of Europe with Africa in spatial concepts such as Atlantropa, Eurafrica, and Panropa. These served the expansion of national empires – fascist Italy claimed Libya as the "Fourth Coast" (quarta sponda) and the Mediterranean as mare nostro – or, as envisaged it, to unite and prepare the Occident for the global competition with America and Asia through a concerted development of African resources. In these geo-political visions, the Mediterranean appeared as a maritime link between Europe and its African provinces. The border between the two continents was abolished, and the relationship between north and south was conceived as a relationship of colonial exploitation.76

Algeria was the model and an extreme example of this trans-Mediterranean shift of the European southern border. After the French conquest (1830–1847), the Ottoman regency was declared a settlement colony in 1838, and then, in 1848, even a part of the national territory. Napoleon III (1808–1873) stopped the state settlement policy and proclaimed Algeria his "Arab Kingdom.” While Muslims were to be equal subjects, the colonial land grab and the destruction of tribal structures persisted in the Second Empire. In 1870, the Third Republic gave the settlers control over the civil administration, which they used to expropriate the Muslims. As the cultivation of the interior was nevertheless proceeding at a slow pace, the colonial administration – after a disastrous phylloxera plague in the hexagon, which destroyed 40 % of the vineyards – “transplanted” wine growers and wine workers from the Midi to Algeria in order to help the colonial economy finally flourish after numerous setbacks. Thanks to free land concessions, cheap credit, bargain Muslim labor, oenological knowledge transfers and technological innovations, they transformed Algeria before the First World War into the world's largest exporter and fourth largest producer of wine. As a consequence, there was a partial assimilation of the natural areas of the South of France and northern Algeria. Algeria seemed to have become the southern extension of the hexagone. As late as the Algerian War (1954–1962), the North African departments were portrayed as an integral part of the nation.77

Mediterranean subjects

The European colonial powers reduced the ethnic-religious complexity of North Africa and the Levant. The French, for example, divided the diverse population of the Ottoman regency of Algiers in 1831 into two legal categories: "Europeans" and "Indigènes."78 While they gradually integrated the native Jews and naturalized them in 1870 without being asked,79 they subjugated the indigenous Muslims in 1881 to a draconian native law.80 Here, a distinction was made between "nomadic" Arabs and "sedentary," supposedly more easily assimilated Berbers.81 Although the Europeans were less brutal in other colonies and protectorates, their "politics of difference" divided the Christians, Jews, and Muslims of the region for a long period.82 It is therefore no coincidence that after decolonization there was an exodus of Christians and Jews from North Africa and West Asia, which led to the ethnic-religious "unmixing" of the population.83

At the same time, however, Europe's imperial regime itself produced "hybrid" subjects that could not be clearly assigned to any "cultural area."84 The history of the European term "Levantine," which at first referred to all inhabitants of the Ottoman port cities of the eastern Mediterranean, was restricted in the 19th century to all non-Muslims permanently resident there and finally to "native" Catholics, bears witness to the bewilderment European travelers experienced about a group that could be qualified neither as "European" nor "Oriental."85 Even the Mediterranean Europeans who immigrated uninvited from the northern coasts and islands of the western Mediterranean to North Africa in the 19th century – Spaniards, Maltese and Italians – were not initially recognized as Occidentals by the French colonial administration, but were rather counted as Africans or Orientals. They were not considered willing or able to promote mise en valeur or even fulfill the mission civilisatrice. They were instead viewed as parasites of the œuvre français and a "fifth column" of rival empires.86 In addition, southern European nations and regions such as Spain and Greece, Mezzogiorno, and Balkans have been excluded from the Occident by Northwestern Europe since the Enlightenment. Parallel to the "Europeanization" of North Africa and the Levant, there was also an "Orientalization" or "Africanization" of Southern Europe, which was thus excluded from concepts of "Western" civilization and modernity.87 Only after the reform of the citizenship law (since 1889, Europeans born on French soil automatically received the citoyenneté88) did a collective identity form among the predominantly Catholic settlers – in distinction from the emancipated Jews and from Paris. In the 1890s, Algeria became a center of French anti-Semitism.89 In the interwar period, the wine wars between the Midi viticole and the North African departments strained the relationship between the metropolis and the colony.90 During decolonization, when about one million settlers fled to France and were "repatriated," this emotional gap deepened. Many French people in the hexagone considered the pieds noirs politically suspect and culturally alien; they felt "betrayed" by the abandonment of their homeland.91 The harkis , those Muslims who had fought for France in the Algerian War and fled from repression after independence, were hit even harder. They had to reapply for French citizenship and were forced to live in ghettoized military camps. Despised as "collaborators" by Algerians on both sides of the Mediterranean, they were simply "Arabs" for many French.92

, those Muslims who had fought for France in the Algerian War and fled from repression after independence, were hit even harder. They had to reapply for French citizenship and were forced to live in ghettoized military camps. Despised as "collaborators" by Algerians on both sides of the Mediterranean, they were simply "Arabs" for many French.92

Braudel regretted the "miserable fate" of the harkis, but generally considered people of different faiths difficult to integrate. In L'identité de la France (1986), his posthumous national history of France, he argued that the religious core of cultures hinders the assimilation of their human bearers: While Jews only "to a very limited extent" detached themselves from their "inner culture," "the main obstacle standing in the way of North African immigrants is the fundamental diversity of cultures."93 In La Méditerranée (1949) Braudel had already developed the theory that cultures (civilisations) were "native to a particular region" and therefore could not be "transplanted." This view would have been suitable for criticizing the French project of assimilating Algeria. Braudel, however, applied it exclusively to Islamic Spain (al-andalus), where the Reconquista had to expel the Muslims who had been forcibly converted because they were "not assimilable."94 In contrast, he would defend French-Algeria until the end of his life. In 1923–1932, he had worked here as a secondary school teacher and university lecturer; a year after arriving, he married the daughter of a settler family from Tiaret in the Oran department. In the Annales, Braudel campaigned for recognition of the agricultural achievements of "European Africa," i.e. the settlers in Algeria. In his Mediterranean book he praised the cultivation of the Tiaret plateau as a positive example of taming nature.95 Braudel's theory of espace culturel, which was later taken up by Samuel P. Huntington (1927–2008) and Niall Ferguson (born 1964), among others,96 was itself in many respects a product of the colonial intertwining of the modern Mediterranean region.

The fact that the region could be understood otherwise even in those days is shown by the example of Gabriel Audisio (1900–1978). His fluid understanding of Mediterranean culture was a product of the transnational (Piedmontese, Romanian, Flemish and niçois) roots of his "nomadic" family, his quick study of Islamic civilization, and his occupational mobility. In the 1930s, the journalist and writer travelled restlessly between Paris and Algiers, his home city of Marseille and other Mediterranean ports for the Algerian tourism authority. In the Cahiers du Sud and the collection of essays La Jeunesse de la Méditerranée (1935), he criticized contemporary Mediterranean concepts such as Louis Bertrand's (1866–1941) "Latin Africa" or Paul Valéry’s (1871–1945) machine à faire de la civilisation as Eurocentric. "Our European perspectives" of the Mediterranean as part of Europe are wrong, and all attempts by European nationalists and regionalists to appropriate the Mediterranean are misguided. For the Mediterranean is the "fatherland" of all its inhabitants. The unity of the region resulted from the "mixing" of its cultures and races, to which Audisio also counted Phoenicians, Arabs, and Jews. The neglect of the region in geological studies on Europe shows that the Mediterranean is a "sixth continent," a "fluid continent" (continent liquide).97

Since the turn of the 21st century, Mediterranean artists, scientists, and marketing strategists have seized on this fluid, transcultural understanding of the region in order to move their cities, islands and regions once again from the peripheries of nations and continents to the center of global interactions.98 Conversely, rigid demarcation lines have also again come to the fore in the region. While the Mediterranean remains the most popular destination for tourists from all over the world, it has become a death zone for migrants from Africa and Asia. In this context, too, we would do well to avoid using spatial concepts such as the Mediterraneum without reflection, but always to explore their genesis, use and consequences. In doing so, we can trace the interactions between the construction of space, on the one hand, and its transformation on the other.

In order to transcend the "metageographies" with which we think, order, and hierarchize the world, de-essentialized, historicized spatial categories such as the Mediterraneum form an ideal starting point. The spatial concept is therefore particularly suitable for overcoming the "myth of the continents."99 As a look at the region's modern history shows, the boundaries between "Africa," "Asia," and "Europe" have become so blurred in this "fluid continent" that it seems appropriate that we understand these units of historical analysis more in their Mediterranean context in the future.

Manuel Borutta

Appendix

Literature

Abécassis, Frédéric et al. (eds.): La bienvenue et l'adieu: Migrants juifs et musulmans au Maghreb (XVe–XXe siècle), Casablanca 2012. URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.cjb.116 (vol. 1) / URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.cjb.123 (vol. 2) / URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.cjb.124 (vol. 3) [2021-01-08]

Abulafia, David: Ein globalisiertes Mittelmeer: 1900–2000, in: David Abulafia (ed.): Mittelmeer: Kultur und Geschichte, Stuttgart 2003, pp. 283–312.

Abulafia, David: Mediterranean History as Global History, in: History and Theory 50,2 (2011), pp. 220–228. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2303.2011.00579.x / URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41300080 [2021-01-08]

Abulafia, David: Das Mittelmeer: Eine Biographie, Frankfurt am Main 2013.

Ageron, Charles-Robert: Histoire contemporaine de l'Algérie, Paris 1979, vol. 2: De l'insurrection de 1871 au déclenchement de la guerre de libération.

Akçam, Taner: The Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire, Princeton, NJ 2012 (Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity). URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400841844 [2021-01-08]

Albera, Dionigi et al. (eds.): Dictionnaire de la Méditerranée, Arles 2016. URL: https://dicomed.mmsh.univ-aix.fr [2021-01-08]

Armitage, David et al. (eds.): Oceanic Histories, Cambridge et al. 2018 (Cambridge Oceanic Histories). URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108399722 [2021-01-08]

Arthurs, Joshua: The Excavatory Intervention: Archaeology and the Chronopolitics of Roman Antiquity in Fascist Italy, in: JMEH 13.1 (2015), pp. 44–58. URL: https://doi.org/10.17104/1611-8944_2015_1_44 / URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26266163 [2021-01-08]

Apostolopoulos, Yorghos: Mediterranean Tourism: Facets of Socioeconomic Development and Cultural Change, London 2006.

Assan, Valérie et al. (eds.): Minorités en Méditerranée au XIXe siècle: identités, identifications, circulation, Rennes 2019.

Atkinson, David: Geopolitics, Cartography and Geographical Knowledge: Envisioning Africa from Fascist Italy, in: Morag Bell et al. (eds.): Geography and Imperialism: 1820–1940, Manchester et al. 1995 (Studies in Imperialism), pp. 265–297.

Audisio, Gabriel: Jeunesse de la Méditerranée, Paris 1935.

Aydin, Cemil: Regionen und Reiche in der politischen Geschichte des Langen 19. Jahrhunderts (1750–1924), in: Jürgen Osterhammel et al. (eds.): 1750–1870. Wege zur modernen Welt, München 2016 (Geschichte der Welt 4), pp. 35–253. URL: https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406641145 [2021-01-08]

Balfour, Sebastian: Deadly Embrace: Morocco and the Road to the Spanish Civil War, Oxford 2002.

Barkey, Karen: Empire of Difference: The Ottomans in Comparative Perspective, Cambridge et al. 2008. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790645 [2021-01-08]

Bayly, Christopher Alan et al. (eds.): Giuseppe Mazzini and the Globalisation of Democratic Nationalism 1830–1920, Oxford et al. 2008 (Proceedings of the British Academy 152). URL: https://doi.org/10.5871/bacad/9780197264317.001.0001 [2021-01-08]

Ben-Yehoyada, Naor: Mediterranean Modernity?, in: Peregrine Horden et al. (eds.): A Companion to Mediterranean History, Chichester 2014 (Wiley Blackwell Companions to History), pp. 108–121. URL: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118519356.ch7 [2021-01-08]

Blais, Hélène / Deprest, Florence: The Mediterranean, a Territory between France and Colonial Algeria: Imperial Constructions, in: European Review of History – Revue europeenne d'histoire 19,1 (2012), pp. 33–57. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2012.643608 [2021-01-08]

Blaschke, Olaf u.a. (eds.): Weltreligion im Umbruch: Transnationale Perspektiven auf das Christentum in der Globalisierung, Frankfurt am Main 2019.

Bono, Salvatore: Piraten und Korsaren im Mittelmeer: Seekrieg, Handel und Sklaverei vom 16. bis 19. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart 2009.

Borutta, Manuel: Nach der Méditerranée: Frankreich, Algerien und das Mittelmeer, in: New Political Literature 56,3 (2011), pp. 405–426. URL: https://doi.org/10.3726/91488_405 [2021-01-08]

Borutta, Manuel: Frankreichs Süden: Der Midi und Algerien, 1830–1962, in: Francia 41 (2014), pp. 201–224. URL: https://doi.org/10.11588/fr.2014.0.40748 / URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-fr-407486 [2021-01-08]

Borutta, Manuel: Braudel in Algier: Die kolonialen Wurzeln der "Méditerranée" und der "spatial turn", in: Historische Zeitschrift 303,1 (2016), S. 1–38. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/hzhz-2016-0285 [2021-01-08]

Borutta, Manuel et al. (eds.): A Colonial Sea: The Mediterranean, in: European Review of History – Revue europeenne d'histoire 19,1 (2012), pp. 1–13. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2012.643609 [2021-01-08]

Borutta, Manuel et al. (eds.): Vertriebene and Pieds-Noirs in Postwar Germany and France: Comparative Perspectives, Basingstoke 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137508416 [2021-01-08]

Borutta, Manuel / Lemmes, Fabian: Die Wiederkehr des Mittelmeerraumes: Stand und Perspektiven der neuhistorischen Mediterranistik, in: New Political Literature 58,3 (2013), pp. 389–419. URL: https://doi.org/10.3726/91493_389 [2021-01-08]

Bourguet, Marie-Noëlle: De la Méditerranée, in: Marie-Noëlle Bourguet et al. (eds.): L'invention scientifique de la Méditerranée: Égypte, Morée, Algérie, Paris 1998 (Recherches d'histoire et de sciences sociales / Studies in History and the Social Sciences 77), pp. 7–28.

Bourguet, Marie-Noëlle et al. (eds.): Enquêtes en méditerranée: Les expéditions françaises d'Égypte, de Morée et d'Algérie ; actes de colloque, Athènes-Nauplie, 8 – 10 juin 1995, Athen 1999.

Bourguinate, Nicolas (eds.): L'invention des Midis: Représentations de l'Europe du Sud, XVIIIe–XXe siècle, Strasbourg 2015 (Sciences de l'histoire). URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pus.13999 [2021-01-08]

Bouyrat, Yann: Devoir d'intervenir? L'intervention "humanitaire" de la France au Liban, 1860, Paris 2013 (Collection Empires).

Braude, Benjamin et al.: Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire: The Functioning of a Plural Society, New York, NY et al. 1982, vol. 1–2.

Braudel, Fernand: La Méditerranée et le Monde méditerranéen à l'époque de Philippe II, Paris 1949, vol. 1.

Braudel, Fernand: Das Mittelmeer und die mediterrane Welt in der Epoche Philipps II., Frankfurt am Main 1990, vol. 1.

Braudel, Fernand: Das Mittelmeer und die mediterrane Welt in der Epoche Philipps II., Frankfurt am Main 1990, vol. 2.

Braudel, Fernand: Mediterrane Welt, in: Fernand Braudel et al. (eds.): Die Welt des Mittelmeeres: Zur Geschichte und Geographie kultureller Lebensformen, Frankfurt am Main 1990, pp. 7–10.

Braudel, Fernand: France, Stuttgart 2009, vol. 2: Die Menschen und die Dinge.

Brehl, Medardus et al. (eds.): Gewaltraum Mittelmeer? Strukturen, Erfahrungen und Erinnerung kollektiver Gewalt im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, in: Zeitschrift für Genozidforschung 17,1/2 (2019). URL: https://doi.org/10.5771/1438-8332-2019-1-2-1 [2021-01-08]

Burbank, Jane / Cooper, Frederick: Imperien der Weltgeschichte: Das Repertoire der Macht vom alten Rom und China bis heute, Frankfurt am Main u.a. 2012.

Burke, Peter: Offene Geschichte: Die Schule der "Annales", Frankfurt am Main 1998.

Burke, Edmund: Toward a Comparative History of the Modern Mediterranean, 1750–1919, in: Journal of World History 23,4 (2012), pp. 907–939. URL: https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2012.0133 / URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41858768 [2021-01-08]

Burr, Viktor: Nostrum mare: Ursprung und Geschichte der Namen des Mittelmeeres und seiner Teilmeere im Altertum, Stuttgart 1932 (Würzburger Studien zur Altertumswissenschaft 4).

Calafat, Guillaume: Une mer jalousée: Contribution à l'histoire de la souveraineté, Méditerranée, XVIIe siècle, Paris 2019.

Calic, Marie-Janine: Südosteuropa: Weltgeschichte einer Region, Munich 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406698316 [2021-01-08]

Caruso, Clelia (eds.): Postwar Mediterranean Migration to Western Europe: Legal and Political Frameworks, Sociability and Memory Cultures = La migration méditerranéenne en Europe occidentale après 1945: droit et politique, sociabilité et mémoires, Frankfurt am Main 2008 (Inklusion, Exklusion 7).

Casale, Giancarlo: The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Oxford 2010. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195377828.001.0001 / URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.30982 [2021-01-08]

Catlos, Brian A.: Kingdoms of Faith: A New History of Islamic Spain, London 2018.

Catlos, Brian A. et al. (eds.): Can We Talk Mediterranean? Conversations on an Emerging Field in Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Cham 2017 (Mediterranean Perspectives). URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55726-7 [2021-01-08]

Chambers, Iain: Mediterranean Crossings: The Politics of an Interrupted Modernity, Durham 2008. URL: https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822388869 [2021-01-08]

Clancy-Smith, Julia Ann: Exoticism, Erasures, and Absence: The Peopling of Algiers, 1830–1900, in: Zeynep Çelik et al. (eds.): Walls of Algier: Narratives of the City Through Text and Image, Los Angeles et al. 2009, pp. 19–61.

Clancy-Smith, Julia Ann: Mediterraneans: North Africa and Europe in an Age of Migration, c. 1800–1900, Berkeley, CA et al. 2011 (The California World History Library 15). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pnxk1 [2021-01-08]

Cole, Juan Ricardo: Die Schlacht bei den Pyramiden: Napoleon erobert den Orient, Stuttgart 2010.

Dainotto, Roberto: Europa (in der Theorie), in: Franck Hofmann et al. (eds.): Fluchtpunkt: Das Mittelmeer und die europäische Krise, Berlin 2017, pp. 36–69.

Davis, Diana K.: Resurrecting the Granary of Rome: Environmental History and French Colonial Expansion in North Africa, Athens, OH 2007 (Ohio University Press Series in Ecology and History).

Davis, Ralph: Aleppo and Devonshire Square: English Traders in the Levant in the Eighteenth Century, London 1967. URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-00557-4 [2021-01-08]

Deprest, Florence: L'invention géographique de la Méditerranée: Éléments de réflexion, in: L'Espace géographique 31,1 (2002), pp. 73–92. URL: https://doi.org/10.3917/eg.311.0073 [2021-01-08]

Dir, Yamina: Bilder des Mittelmeer-Raumes: Phasen und Themen der ethnologischen Forschung seit 1945, Münster 2005 (EuroMed: Studien zur Kultur- und Sozialanthropologie des euromediterranen Raumes 1).

Dunlop, Douglas Morton: Baḥr al-Rūm, in: P. J. Bearman et al. (eds.): The Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Leiden 2012. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_1065 [2021-01-08]

Dursteler, Eric R.: Venetians in Constantinople: Nation, Identity, and Coexistence in the Early Modern Mediterranean, Baltimore, MD 2006 (The Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science 124,2).

Eisenmenger, Daniel: Die vergessene Verfassung von Korsika 1755: Der gescheiterte Versuch einer modernen Nationsbildung, in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 61,7/8 (2010), pp. 430–446.

Eldem, Edhem: French Trade in Istanbul in the Eighteenth Century, Leiden 1999 (The Ottoman Empire and its Heritage 19).

Eldem, Edhem / Goffman, Daniel / Masters, Bruce Alan: The Ottoman City between East and West: Aleppo, Izmir, and Istanbul, Cambridge 2005 (Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization).

Ellena, Liliana: Political Imagination, Sexuality and Love in the Eurafrican Debate, in: European Review of History / Revue europeenne d'histoire 11,2 (2004), pp. 241–272. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/1350748042000240578 [2021-01-08]

Epstein, Steven A.: Hybridity, in: Peregrine Horden et al. (eds.): A Companion to Mediterranean History, Chichester 2014 (Wiley Blackwell Companions to World History), pp. 345–358. URL: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118519356.ch22 [2021-01-08]

Fabre, Thierry: La France et la Méditerranée: Généalologies et représentations, in: Jean-Claude Izzo et al. (eds.): La Méditerranée française, Paris 2000 (Les représentations de la Méditerranée 9), pp. 13–152.

Fabre, Thierry: Metaphors for the Mediterranean: Creolization or Polyphony?, in: Mediterranean Historical Review 17,1 (2002), pp. 15–24. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/714004596 [2021-01-08]

Faroqhi, Suraiya: Das Osmanische Reich und die islamische Welt, in: Wolfgang Reinhard (ed.): 1350–1750. Weltreiche und Weltmeere, München 2014 (Geschichte der Welt), pp. 219–367. URL: https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406641138 [2021-01-08]

Feichtinger, Moritz / Malinowski, Stephan: "Eine Million Algerier lernen im 20. Jahrhundert zu leben": Umsiedlungslager und Zwangsmodernisierung im Algerienkrieg 1954–1962, in: Journal of Modern European History 8,1 (2010), pp. 107–135. URL: https://doi.org/10.17104/1611-8944_2010_1_107 / URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26265906 [2021-01-08]

Ferguson, Niall: Der Westen und der Rest der Welt: Die Geschichte vom Wettstreit der Kulturen, Berlin 2013.

Ferro, Marc: Colonization: A Global History, London et al. 1997

Fogarty, Richard Standish: Race and War in France: Colonial Subjects in the French Army, 1914–1918, Baltimore, MD 2008 (War / Society / Culture).

Frank, Alison: Continental and Maritime Empires in an Age of Global Commerce, in: East European Politics and Societies 25,4 (2011), pp. 779–784. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325411399123 [2021-01-08]

Frank, Alison: The Children of the Desert and the Laws of the Sea: Austria, Great Britain, the Ottoman Empire, and the Mediterranean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century, in: American Historical Review 117,2 (2012), pp. 410–444. URL: https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.117.2.410 / URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23310742 [2021-01-08]

Frankel, Jonathan: The Damascus Affair: "Ritual Murder", Politics, and the Jews in 1840, Cambridge 1997.

Friday, Ulrike: 'Cosmopolitanism' and 'Conviviality'? Some Conceptual Considerations Concerning the Late Ottoman Empire, in: European Journal of Cultural Studies 17,4 (2014), pp. 375–391. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549413510417 [2021-01-08]

Fuhrmann, Malte: Meeresanrainer – Weltenbürger? Zum Verhältnis von hafenstädtischer Gesellschaft und Kosmopolitismus, in: Comparativ 17,2 (2007), pp. 12–26. URL: https://doi.org/10.26014/j.comp.2007.02.02 [2021-01-08]

Fuhrmann, Malte: Port Cities of the Eastern Mediterranean: Urban Culture in the Late Ottoman Empire [forthcoming].

Carter, Malte et al. (eds.): The Late Ottoman Port-Cities and Their Inhabitants: Subjectivity, Urbanity, and Conflicting Orders, in: Mediterranean Historical Review 24,2 (2009), pp. 71–78. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/09518960903487909 [2021-01-08]

Gall, Alexander: Das Atlantropa-Projekt: Die Geschichte einer gescheiterten Vision; Herman Sörgel und die Absenkung des Mittelmeers, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1998.

Gautier, Emile-Félix: Les siècles obscurs du Maghreb: L'islamisation de l'Afrique du Nord, Paris 1927 (Bibliothèque historique).

Gekas, Sakis: Xenocracy: State, Class and Colonialism in the Ionian Islands, 1815–1864, New York 2017.

Gekas, Sakis / Grenet, Mathieu: Trade, Politics and City Space(s) in Mediterranean Ports, in: Carola Hein (ed.): Port Cities: Dynamic Landscapes and Global Networks, Abingdon et al. 2011, pp. 89–103.

Georgelin, Hervé: La fin de Smyrne: Du cosmopolitisme aux nationalismes, Paris 2005. URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.editionscnrs.2498 [2021-01-08]

Geulen, Christian: Geschichte des Rassismus, Munich 2006. URL: https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406623806 [2021-01-08]

Ginio, Eyal: Ottoman Culture of Defeat: The Balkan Wars and Their Aftermath, London 2016 (Mediterraneans). URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190264031.001.0001 [2021-01-08]

Greene, Molly: A Shared World: Christians and Muslims in the Early Modern Mediterranean, Princeton, NJ 2000. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400844494 [2021-01-08]

Greene, Molly: The Mediterranean Sea, in: David Armitage et al. (eds.): Oceanic Histories, Cambridge et al. 2018, pp. 134–155. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108399722.006 [2021-01-08]

Hansen, Peo / Jonsson, Stefan: Eurafrica: The Untold History of European Integration and Colonialism, London et al. 2015 (Theory for a Global Age). URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472544506 [2021-01-08]

Harris, William Vernon (ed.): Rethinking the Mediterranean, Oxford et al. 2005.

Hartmann, Heinrich: Eigensinnige Musterschüler: Ländliche Entwicklung und internationales Expertenwissen in der Türkei (1947–1980), Frankfurt am Main 2020.

Henry, Jean-Robert: La norme et l'imaginaire, construction de l'altérité juridique en droit colonial algérien, in: Procès 18 (1987–1988), pp. 13–27.

Hershenzon, Daniel: The Captive Sea: Slavery, Communication, and Commerce in Early Modern Spain and the Mediterranean, Philadelphia 2018. URL: https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812295368 [2021-01-08]

Hess, Andrew C.: The Forgotten Frontier: A History of the Sixteenth-Century Ibero-African Frontier, Chicago 1978 (Publications of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies 10). URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.00893 [2021-01-08]

Holland, Robert: Blue-Water Empire: The British in the Mediterranean since 1800, London 2012.

Horden, Peregrine et al. (eds.): A Companion to Mediterranean History, Chichester 2014 (Wiley Blackwell Companions to History). URL: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118519356 [2021-01-08]

Horden, Peregrine / Purcell, Nicholas: The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History, London 2000.

Horden, Peregrine / Purcell, Nicholas: The Mediterranean and "The New Thalassology," in: The American Historical Review 111,3 (2006), pp. 722–740. URL: https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.111.3.722 / URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/ahr.111.3.722 [2021-01-08]

Huber, Valeska: Channelling Mobilities: Migration and Globalisation in the Suez Canal Region and Beyond, 1869–1914, Cambridge 2013. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139344159 [2021-01-08]

Huntington, Samuel P.: Kampf der Kulturen: Die Neugestaltung der Weltpolitik im 21. Jahrhundert, 7th ed., Munich 1998.

Ilbert, Robert: Alexandrie, 1830–1930: Histoire d'une communauté citadine, Cairo 1996.

Ilbert, Robert et al. (eds.): Les représentations de la Méditerranée, vol. 1–10, Paris 2000.

International Centre for Advanced Mediterranean Agronomic Studies (CIHEAM): Mediterra 2012: The Mediterranean Diet for Sustainable Regional Development, Paris 2012 (Mediterra).

Isabella, Maurizio et al. (eds.): Mediterranean Diasporas: Politics and Ideas in the Long 19th Century, London 2015.

Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum sive Originum, after the critical edition by W. M. Lindsay, Oxford 1911. URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-db-id4156568505 [2021-01-08]

Isnard, Hildebert: La vigne en Algérie: Étude Géographique, Gap 1951–1954, vol. 1–2.

Jansen, Jan: Die Erfindung des Mittelmeerraums im kolonialen Kontext: Die Inszenierungen des "lateinischen Afrika" beim Centenaire de I'Algerie française 1930, in: Frithjof Benjamin Schenk u.a. (eds.): Der Süden: Neue Perspektiven auf eine europäische Geschichtsregion, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2007, pp. 175–205. URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-173656 [2021-01-08]

Jansen, Jan C.: Unmixing the Mediterranean? Migration, demografische "Entmischung" und Globalgeschichte, in: Boris Barth et al. (eds.): Globalgeschichten: Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2014 (Globalgeschichte 17), pp. 289–313. URL: https://www.academia.edu/23328387 [2021-01-08]

Jaspert, Nikolas / Kolditz, Sebastian: Seeraub im Mittelmeerraum: Bemerkungen und Perspektiven, in: Nikolas Jaspert et al. (eds.): Seeraub im Mittelmeerraum: Piraterie, Korsarentum und maritime Gewalt von der Antike bis zur Neuzeit, Paderborn 2013 (Mittelmeerstudien 3), pp. 11–37. URL: https://doi.org/10.30965/9783657778690_003 [2021-01-08]

Jensen, Geoffrey: The Peculiarities of 'Spanish Morocco': Imperial Ideology and Economic Development, in: Mediterranean Historical Review 20.1 (2005), pp. 81–102. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/09518960500204681 [2021-01-08]

Julien, Charles-André: Histoire de l'Algérie contemporaine: La conquête et les débuts de la colonisation (1827–1871), Paris 1964.

Kaiser, Wolfgang: Le commerce des captifs: Les intermédiaires dans l'échange et le rachat des prisonniers en Méditerranée, XVe–XVIIIe siècle, Rom 2008 (Collection de l'École Française de Rome 406). URL: http://digital.casalini.it/9782728308057 [2021-01-08]

Kaiser, Wolfgang: Mediterrane Welt, in: Friedrich Jaeger (ed.): Enzyklopädie der Neuzeit, Stuttgart 2008, vol. 8: Manufaktur – Naturgeschichte, col. 249–260. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2352-0248_edn_COM_309117 [2021-01-08]

Kaspi, André: Histoire de l'Alliance israélite universelle: De 1860 à nos jours, Paris 2010.

Khuri-Makdisi, Ilham: The Eastern Mediterranean and the Making of Global Radicalism, 1860–1914, Berkeley, CA et al. 2010 (The California World History Library 13). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pq0nq [2021-01-08]

Knöbl, Wolfgang: Southern Europe and the Master Narratives of 'Modernization' and 'Modernity', in: Martin Baumeister et al. (eds.): Southern Europe? Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece from the 1950s until the present day, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2015, pp. 173–199.

Koller, Markus: Osmanistik, in: Mihran Dabag (eds.): (eds.): Handbuch der Mediterranistik: Systematische Mittelmeerforschung und disziplinäre Zugänge, Paderborn 2015 Mittelmeerstudien 8), pp. 353–361. URL: https://doi.org/10.30965/9783657766277_023 [2021-01-08]

Krstić, Tijana: Moriscos in Ottoman Galata, 1609–1620s, in: Mercedes García-Arenal et al. (eds.): The Expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain: A Mediterranean Diaspora, Leiden 2014 (Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World 56), pp. 269–285. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004279353_013 [2021-01-08]

Labanca, Nicola: Oltremare: Storia dell'espansione coloniale italiana, Bologna 2002.

Lafi, Nora: Kosmopolitismus als Governance: Das Beispiel des Osmanischen Reiches, in: Bernhard Gißibl et al. (eds.): Bessere Welten: Kosmopolitismus in den Geschichtswissenschaften, Frankfurt am Main 2017, pp. 317–342.

Lafi, Nora: Esprit civique et organisation citadine dans l'Empire ottoman (XVe-XXe siècles), Leiden 2018 (The Ottoman Empire and its Heritage 64). URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004364516 [2021-01-08]

Lanzmann, Claude (ed.): Harkis 1962–2012: Les mythes et les faits, Paris 2011 (Les temps modernes 666).

Laurens, Henry: L'expédition d'Egypte: 1798–1801, Paris 1997.

Levy, Avigdor (eds.): Jews, Turks, Ottomans: A Shared History, Fifteenth Through the Twentieth Century, Syracuse, NY 2002 (Modern Jewish History).

Lewis, Martin W. / Wigen, Kären: The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography, Berkeley, CA 1997. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pnv6t [2021-01-08]

Liauzu, Claude: L'Europe et l'Afrique méditerranéenne: De Suez (1869) à nos jours, Paris 1994 (Questions au XXe siècle 62).

Liauzu, Claude: Histoire des migrations en Méditerranée occidentale, Brussels 1996 (Questions au XXe siècle 83).

Lorcin, Patricia M. E.: Imperial Identities: Stereotyping, Prejudice and Race in Colonial Algeria, London et al. 1995

Lorcin, Patricia M. E.: Rome and France in Africa: Recovering Colonial Algeria's Latin Past, in: French Historical Studies 25,2 (2002), pp. 295–329. URL: https://doi.org/10.1215/00161071-25-2-295 [2021-01-08]

Lupo, Salvatore: The Two Mafias: A Transatlantic History, 1888–2008, New York 2015 (Italian and Italian American Studies). URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137491374 [2021-01-08]

Mansel, Philip: Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean, New Haven, CT 2010.

Marin, Brigitte: Historiographie, in: Dionigi Albera et al. (eds.): Dictionnaire de la Méditerranée, Arles 2016, pp. 624–640. URL: http://dicomed.mmsh.univ-aix.fr/Pages/notices/dicomed-082.aspx [2021-01-08]

Marseille-Provence 2013 (Marseille): Marseille-Provence 2013: D'Europe et de Méditerranée: candidature pour la capitale européenne de la culture sous l'égide d'Albert Camus qui aura 100 ans en 2013, Marseille 2009.

Matar, Nabil: The "Mediterranean" through Arab Eyes in the Early Modern Period: From Rumi to the "White In-Between Sea", in: Judith E. Tucker (ed.): The Making of the Modern Mediterranean: Views from the South, Oakland, CA 2019, pp. 16–35. URL: https://content.ucpress.edu/title/9780520304598/9780520304598_chapterone.pdf / URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dt10.7 [2021-01-08]

Mauelshagen, Franz: "Anthropozän": Plädoyer für eine Klimageschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, in: Zeithistorische Forschungen 9,1 (2012), pp. 131–137. URL: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-1606 [2021-01-08]

McCormick, Michael: Origins of the European Economy: Communications and Commerce, A. D. 300–900, Cambridge 2001. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107050693 [2020-12-14]

McNeill, John Robert: The Mountains of the Mediterranean World: An Environmental History, Cambridge 2002 (Studies in Environment and History). URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511529023 [2021-01-08]

Meier-Braun, Karl-Heinz: Schwarzbuch Migration: Die dunkle Seite unserer Flüchtlingspolitik, München 2018 (Schriftenreihe der Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung 10285). URL: https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406721113 [2021-01-08]

Meynier, Gilbert: Les Algériens et la guerre de 1914–1918, in: Abderrahmane Bouchène et al. (eds.): Histoire de l'Algérie à la période coloniale, 1830–1962, Paris et al. 2012, pp. 230–234. URL: https://www.cairn.info/histoire-de-l-algerie-a-la-periode-coloniale--9782707178374-page-229.htm [2021-01-08]

Miller, Susan Gilson: A History of Modern Morocco, Cambridge 2013. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139045834 [2021-01-08]

Mishra, Pankaj: Aus den Ruinen des Empires: Die Revolte gegen den Westen und der Wiederaufstieg Asiens, Frankfurt am Main 2013.

Morack, Ellinor: The Dowry of the State? The Politics of Abandoned Property and the Population Exchange in Turkey, 1921–1945, Bamberg 2013 (Bamberger Orientstudien 9). URL: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-485106 [2021-01-08]

Morris, Ian: Mediterraneanization, in: Mediterranean Historical Review 18,2 (2003), pp. 30–55. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/0951896032000230471 [2021-01-08]

Nicolet, Claude et al. (eds.): Mégapoles méditerranéennes: Géographie urbaine rétrospective, Rome et al. 2000 (Collection de l'École Française de Rome 261).

Osterhammel, Jürgen: Die Verwandlung der Welt: Eine Geschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts, 2nd ed., Munich 2009. URL: https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406615016 [2021-01-08]

Osterhammel, Jürgen / Petersson, Niels P.: Geschichte der Globalisierung: Dimensionen, Prozesse, Epochen, 4th revised ed., Munich 2007 (Beck's series 2320).

Panzac, Daniel: Les corsaires barbaresques: La fin d'une épopée 1800–1820, Paris 1999 (Méditerranée).

Paulmann, Johannes: The Straits of Europe: History at the Margins of Continent, in: Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Washington 52 (2013), pp. 7–28. URL: https://www.ghi-dc.org/fileadmin/publications/Bulletin/bu52.pdf [2021-01-08]

Pemble, John: The Mediterranean Passion: Victorians and Edwardians in the South, Oxford et al. 1987.

Pergher, Roberta: Mussolini's Nation Empire: Sovereignty and Settlement in Italy's Borderlands, 1922–1943, Cambridge 2017 (New Studies in European History). URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108333450 [2021-01-08]

Philippson, Alfred: Das Mittelmeergebiet: Seine geographische und kulturelle Eigenart, 4th distributed ed., Wiesbaden 1922. URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-16175-2 [2021-01-08]

Pink, Johanna: Geschichte Ägyptens: Von der Spätantike bis zur Gegenwart, München 2014 (Beck'sche Reihe 6163). URL: https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406667145 [2021-01-08]

Pirenne, Henri: Mahomet et Charlemagne, in: Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire 1,1 (1922), pp. 77–86. URL: https://doi.org/10.3406/rbph.1922.6157 [2021-01-08]

Plaggenborg, Stefan: Ordnung und Gewalt: Kemalismus – Faschismus – Sozialismus, Munich 2012. URL: https://doi.org/10.1524/9783486714098 [2021-01-08]

Pons, Pau Orbrador: Cultures of Mass Tourism: Doing the Mediterranean in the Age of Banal Mobilities, Farnham 2009.

Prochaska, David: History as Literature, Literature as History: Cagayous of Algiers, in: American Historical Review 101,3 (1996), pp. 670–711. URL: https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/101.3.671 / URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2169419 [2021-01-08]

Purcell, Nicholas: Unnecessary Dependences: Illustrating Circulation in Pre-Modern Large-scale History, in: James Belich et al. (eds.): The Prospect of Global History, Oxford 2016, pp. 65–79. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198732259.003.0004 [2021-01-08]

Rappas, Alexis: Cyprus in the 1930s: British Colonial Rule and the Roots of the Cyprus Conflict, London 2014. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780755623914 [2021-01-08]

Reid, Donald M.: Whose Pharaohs? Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian Identity from Napoleon to World War I, Berkeley, CA 2002. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.90010 [2021-01-08]

Ressel, Magnus: Zwischen Sklavenkassen und Türkenpässen: Nordeuropa und die Barbaresken in der Frühen Neuzeit, Berlin 2012 (Pluralisierung & Autorität 31). URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110288575 [2021-01-08]

Riall, Lucy: Garibaldi: Invention of a Hero, New Haven, CT et al. 2008. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1np8sf [2021-01-08]

Richter, Dieter: Der Süden: Geschichte einer Himmelsrichtung, Berlin 2009.

Roberts, Sophie B.: Citizenship and Antisemitism in French Colonial Algeria: 1870–1962, Cambridge 2017. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316946411 [2021-01-08]

Rodogno, Davide: Against Massacre: Humanitarian Interventions in the Ottoman Empire, 1815–1914, Princeton 2011 (Human Rights and Crimes Against Humanity).

Ruedy, John: Modern Algeria: The Origins and Development of a Nation, 2nd ed., Bloomington, IN et al. 2005.

Ruel, Anne: L'invention de la Méditerranée, in: Vingtième Siècle 32,1 (1991), pp. 7–14. URL: https://doi.org/10.3406/xxs.1991.2449 [2021-01-08]

Said, Edward W.: Orientalismus, Frankfurt am Main 2009.

Savage-Smith, Emilie: Cartography, in: Peregrine Horden et al. (eds.): A Companion to Mediterranean History, Chichester 2014 (Wiley Blackwell Companions to History), pp. 184–199. URL: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118519356.ch12 [2021-01-08]

Schayegh, Cyrus: The Middle East and the Making of the Modern World, Cambridge, MA et al. 2017. URL: https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674981096 [2021-01-08]

Schenk, Frithjof Benjamin et al. (eds.) (2007): Der Süden: Neue Perspektiven auf eine europäische Geschichtsregion, Frankfurt am Main u.a. 2007.

Schmitt, Carl: Die Raumrevolution, in: Das Reich 19 (1940), p. 3.

Schmitt, Oliver Jens: Levantiner: Lebenswelten und Identitäten einer ethnokonfessionellen Gruppe im osmanischen Reich im "langen 19. Jahrhundert", Munich 2005 (Südosteuropäische Arbeiten 122).