Lesen Sie auch die Beiträge "Childbirth without pain" und "Midwives in Europe" in der EHNE.

Introduction

The hospital may be defined as "a place where sick people stay for longer periods of time for examination and treatment."1 Few things, in fact, seem more natural than the idea that human communities of all cultures, eras, and regions maintain separate spaces to care for and, if possible, heal their ailing members. At second glance, however, the word "hospital", which is used in numerous German dialects and most European languages, raises questions about its proper translation from Latin into German as "Gasthaus (guesthouse)."2 In German-language history of hospitals one soon encounters the use of two words in the sense of a chronological sequence: "from (traditional) hospital to (modern) Krankenhaus (house for the diseased)."3 This usage is not uncontroversial,4 however, especially due to the tremendous variety among medieval hospitals, obviating a reasonably handy definition.5 While from the point of view of medical history the medieval hospital can be seen as the predecessor of the modern hospital, economic and financial history just as plausibly suggests it is the origin of the modern savings bank. Therefore, before discussing a regionally specific hospital typology – as in a Europe-wide comparison – a differentiated hospital historiography based on sub-disciplines, not national distinctions, must be considered. The (medieval) hospital is simultaneously the subject of legal, economic, medical, architectural, ecclesiastical, religious, urban and national history, to name just the most important areas of study. Each has a distinguished research tradition that goes back more than a hundred years and can no longer be overlooked. In this context, a cultural and social history of poverty and care emerges. Only a small part can be represented here, however, due to the focus on "medical" aspects in the broadest sense and the aforementioned fragmentary line of tradition "from hospital to Krankenhaus."6

Beginning with the German word Krankenhaus, two historical questions arise. The first question concerns transformations in the quality of being "sick". The meaning of being "sick" has changed since the end of the Middle Ages from denoting generally "weak" or "feeble" to the opposite of "healthy" (from Latin infirmus, debilis to aegrotus).7 The quality of being "sick" thus reflects a set of medical circumstances in the broadest sense that further entails a change of knowledge about human beings and their physical and mental states. The second question concerns the spatial constructions – the special places of care, of separation and isolation of those people who were judged to be "sick" according to the prevailing notions and the most general understanding of "medical" concepts.

In the following discussion, when the hospital is conceived as a "knowledge space", it is done with reference to the sources. At the same time, there will be a focus on the conditions in German-speaking Europe.8 This will take place in two different respects, which cannot be completely separated from each other. First, there will be an examination of the local quality of the spaces allocated to the sick in the course of history, in particular to the treatment of the sick by medicine and society.9 Above all, it will be necessary to enquire what knowledge and experiences have been accumulated and exchanged in hospitals. To this end, the initial emphasis is on the division of healthy and sick members of a society into separate spaces ("Exclusion and inclusion"). Second, this contribution considers how the "hospital" was configured as a special site by the transforming knowledge of "health, illness, and healing." Third, attention will be paid to the question of which spaces of knowledge and experience ultimately overlapped and interpenetrated in the specialized "hospital" space ("Knowledge and experience"). Such spaces include those where people are being treated and their caretakers; where a special economy prevails with its various administrators; and where the sick and their visitors are separated.

Exclusion and inclusion

Exclusion

Excluding sick people from the ostensibly healthy community in order to provide them with special care in special places set up for this purpose – i.e. hospitals – contradicts the essence of rational Mediterranean and Western medical science going back over 2,000 years. From its emergence, establishment, and consolidation in the half millennium between the foundational figures of Hippocrates of Kos and Galenus of Pergamon to the middle of the 19th century, there is no known genuine medical argument for removing the sick from their everyday environment for the examination and treatment of their diseases. The definition cited at the outset is convincing in its simplicity, yet it belongs to a longstanding modern form of rationality that is not actually medical in nature. By contrast, Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland (1762–1836), director of the Berlin Charité still remarked unequivocally in 1809: "The treatment of the sick in their homes is always preferable to that in the hospital, as long as it is possible."10

Nevertheless, the concept of exclusion is fundamental to the Judeo-Christian tradition of community. It is related to the banishment of "impure" members from the settlement community that considers itself "pure" in the sense of the Book of Leviticus of the Torah, the Hebrew Bible, and the Old Testament of the Christians. The Vulgate puts it as follows: "omni tempore quo leprosus est et inmundus solus habitabit extra castra."11

The Bible, regarded as the directly revealed Word of God, was central to the self-understanding of different cultures. For the history of societies since late antiquity, it is hard to overestimate the significance of the fact that the term "λέπρα" ("leprosy") was already chosen by Jewish scholars for the Hebrew term "Tzaraath" ("impurity"), which Martin Luther (1483–1546) rendered as "Aussatz", which means as much as "being put aside" or "abandonment" and implies being excluded from society. In ancient times, the Jews translated their sacred writings and religious laws into the Greek of the Septuagint (the oldest continuous translation of the Hebrew Bible into the ancient Greek vernacular of the time). This term for "impurity" found its way unchanged in its Latin form "lepra" into the Vulgate and thus into the Bible text that was used exclusively in Western Roman Christendom for about a millennium. In this way, a social practice rooted in ritual was endowed with a term from medical terminology and thus was transformed into a "disease" and a subject of medicine.

The fact that the term "lepra" acquired a completely new meaning within medicine during the transitional and formative phase of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages had momentous consequences. In line with Hippocratic medicine, the Septuagint still used the word to designate a rather unspecific and harmless whitish, scaly skin lesion.12 This Levitical "impurity" was then referenced several times in New Testament corpus, now against the backdrop of Jesus's special attention to the pariahs whom he could "heal" (in the sense of "purify").13 But in the medical literature of the following centuries, "leprosy" became a "cancer of the whole body" that was usually incurable and accompanied by dramatic bodily deterioration.14 This, however, fundamentally changed the Bible's interpretation: Henceforth it could be assumed – without any change to the text – that the corresponding passages in both Testaments meant a cruelly disfiguring and incurable disease. In turn, this had an impact on medieval and early modern medicine. The latter was now charged with the task reserved for the priests in the Hebrew purity laws of recognizing and interpreting signs of leprosy in order to reliably identify the "impure" people who were to be reinterpreted as "sick."

A literal interpretation of the text of the Old Testament undoubtedly suggested to the Christian-identifying authorities of the Middle Ages and the (early) modern era that they should expel people suffering from leprosy from the community of settlers

In the context of the modern era, the classification of markings on the surface of the body signifying "impurity" was increasingly assigned to the domain of medical science. The divinely imparted ability that lay with the Old Testament priest thus gave way to a rationally founded and trainable ability for making reliable diagnoses to "cast out" or banish a person as necessary

From the 15th and 16th centuries onward, various skin irregularities (such as "scabies", "mange", "scabs", and "pox"/"the French disease"/"syphilis") were increasingly portrayed as "ugly" or "hideous" bodily markings that could or should trigger the exclusion of the afflicted. At the same time, there was a wide-ranging typology of leprosaria. Alongside medieval leper colonies, there were poxhouses (as sanatoriums for the French disease/syphilis) and plague-houses

The leprosy tradition was perpetuated by the discourse on "dangerous" and communicable diseases, which should be confined to isolated institutions whenever possible. In the 16th century, the Frankfurt physician Joachim Strupp (1530–1606) came up with two types of hospitals for this purpose: A "middle house / of the common impure or sick" serving the segregation as well as "the hospitals and valuable god houses / which nevertheless must serve common need / quite often so confined / and in such obscene words / as reported above / situated / so that even the healthy ones in it / who must serve others become weak / how should then the weak ones recover in here?"18 It is quite characteristic that Strupp no longer designates the leprosy-house as a hospital. In the narrower hospital discourse of the early modern period, the term leprosy refers predominantly to circumstances in which admission to an (inner-city) hospital was not possible.

The process of banishment from the city – albeit under opposing conditions – experienced a certain revival in the "lunatic asylum" of the early 19th century. The point of departure for this consideration was in fact the disease-inducing "impurity" of the urban way of life. Maximilian Jacobi (1775–1858), for example, made the following appeal: "The location of the institution is to be cheerful, in a pleasant, fertile, hilly, moderately busy area, not devoid of meadows and deciduous forests, suitable to evoke manifold beneficial impressions on the mind and inviting one to take a leisurely stroll."19 Buoyed by the argument of the "unhealthy (big) city", sanatoria were established in the second half of the 19th century for the chronically or protractedly ill in rural settings such as in Bournemouth

At the same time, rapid urban growth meant that isolation facilities formerly located outside cities – such as Berlin's Charité, which was originally built as a plague house – suddenly found themselves no longer in suburbia but in inner-city locations. From the late imperial period to the present,21 large hospitals

Inclusion

Starting in the High Middle Ages, the process of excluding the "impure" from the (wherever possible) "pure" community of settlers was preferably accompanied in Christian communities by the confinement of the "impure" in a leprosarium

The more exclusive the promise of care being fulfilled by institutionalized medicine, the greater its power to normalize the behavior of those being cared for. Legitimacy was characterized by uniform knowledge, standardized forms of university training, and officially authorized licensing regulations that implied the prohibition of alternative forms of healing. If a hospital is to be examined as a "total institution"23 or "institution of confinement,"24 this dialectic of exclusion and inclusion, of "social safety and social disciplining,"25 must be taken into account. The history of the hospital emerges as the history of an institution which, in the course of its medicalization, molds the sick into patients who submit to institutional self-legislation. Ultimately, the hospitals can be treated as laboratories of medicalization and its avant-garde.26

However, in the pre-modern era, one cannot speak of a rigid confinement of lepers and the hospitalized.27 In fact, not all people of the Middle Ages and the early modern era who qualified as "lepers" lived in leprosoria. Rather quite a considerable number existed as vagabonds

Admission to leprosaria was usually purchased as a benefice or by means of entry fees. In case of blatant violations of the hospital bylaws, expulsions were issued and also carried out. Moreover, the regular activities of the lepers living in the leprosarium included visiting the city to beg at fixed times and places. Sources speak of people who were cured after several years in the leprosarium and of lepers cohabitating with their "healthy" partners. Lepers of different leprosaria also married. The medieval and early modern leprosorium thus already had "permeable walls."28

Admittance to a medieval or early modern hospital was preceded by an examination of "hospitalability." Apart from indigence, it was determined whether these persons had a (possibly graduated) right of residence or citizenship and did not suffer from a "dangerous" disease that might have led to treatment in a specialized hospital. The determination of "neediness" not only asked about sufficient financial means, but also about the ability to help oneself or to be helped in the home. This meant not only income and property, but also explicitly the physical condition of the person. A St. Gallen order of 1228, for instance, mentions in this sense "all miserable sick, who because of their illness and age can no longer help themselves."29 Consistently in the European hospital of the Middle Ages reference is made to poverty and/or illness of those who were cared for there.30 From the 15th century onward, primarily in foundation hospitals under municipal (financial) supervision, the tendency to assign particular conditions of poverty and illness to specific types of hospital care or even public care increased. In addition, there were various ways in which people could buy their way into a hospital. It was not uncommon for craftsmen's organizations such as guilds or even family foundations to have secured a (small) number of benefices so that guildsmen or less wealthy family members could be temporarily accommodated in the hospital if necessary. In addition, the hospitals sold life annuities. Only the last type of hospital beneficiary was not subject to the ongoing indigence test, which determined whether the patient was fit to be discharged.

In addition to policies of admission to the hospitals, there have been explicit rules of discharge since the 16th century. The latter are relevant in light of the view of hospitals as "closed institutions." From the Nuremberg Heilig-Geist-Spital, for example, we find an "oath of the examiner" (Eid der Schauerin) from the year 1565. The examiners not only responded to requests for admission, but also regularly inspected the physical well-being of the patients during their tours of the hospital. The decision to release the patients then followed their recovery.31 Indeed, confinement was not fundamentally designed to be permanent at the hospital.

Michel Foucault (1926–1984) identified the period around 1800 as the birth of the clinic. In his book of the same name, he conceives of the hospital as the setting for the genesis of the "medical gaze." However, in the medical literature around the same time, there were also considerable reservations about the hospital. Instead, preference was given to the "visiting institution," i.e. the care of sick (poor) people in their homes by (publicly) financed physicians.32 Their most famous proponent is the already cited Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland, who lamented in 1809: "The more people are treated en masse, the more the sense of the individual is lost." He added: "(T)he more people are crowded together en masse, the more evil is also generated among them through the degradation of the air and the corruption of morals."33

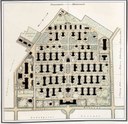

In the German-speaking world, the debate entered the public domain primarily due to a dispute between the physicians Daniel Nootnagel (1753–1836) and Philipp Gabriel Hensler (1733–1805) in Hamburg in 1785.34 In Hamburg – as in Bremen and in Lübeck – an outpatient form of poor relief had been introduced in the 1770s and 1780s, which included care for the sick poor. It was based on a principle that was christened the "Elberfeld System" in the 19th century. The city was divided into manageable quarters in which caretakers and doctors for the poor were in close contact with the respective population. The two founders, Caspar Voght (1752-1839) and Johann Georg Büsch (1728–1800), popularized the system in at least half of Europe.35

After visiting the sick in this capacity, Hamburg physicians fell ill and died. This caused Hensler to distance himself from the visitation practice. He called instead for a hospital that would preserve the health of the physicians, because: "An equivalence cannot be made if an uninherited elector or his trumpeter is blighted by smallpox. And it is also not entirely the same thing if a promising young doctor or a chap who's a craftsman dies."36 Although his antagonist, Nootnagel, was entirely in agreement here, he was not convinced by the argument of the risk of infection in the cottages of the sick poor. In his rebuttal, he claimed rather that this danger was considerably greater in the hospital. Moreover, the large number of patients and their illnesses in the hospital would at most likely overwhelm the physicians. By the same token, it was only the precise examination of the most conspicuous symptoms of illness, but of the entire life circumstances, that gives any hopes of a successful cure. Finally, Nootnagel mentioned how the encounter between caregivers and those receiving care in the hospital was completely unsuited to arriving at a suitable cure. In hospitals, it is certainly possible to establish discipline in a quasi-paramilitary manner. However, patient compliance is much more likely if it is based on their gratitude towards the doctors visiting them in their suffering.

The consideration of more or less enclosed "places of confinement" is tied to the fact that the 19th-century bourgeois world saw three types of institutions for civic rehabilitation: the prison, the insane asylum, and (broadly understood) the hospital. Remarkably, all three claimed quite extensive power of disposal over individuals for a certain period of time to then release them again afterwards as healed or at least improved and ultimately useful members of society. The idea of the three institutions as reformatories is based on reform discourses that only deviate slightly chronologically.37 Each one was authoritatively analyzed by Michel Foucault.38 The curative function put forward as the essential reason for the respective institution's usefulness was still just a hypothesis. In order to actually prove their benefit, the individual institutions needed to be able to select their clientele on their own from the standpoint of presumed curability. As a result, there was adverse competition around the troublesome, i.e. incurable, care recipients. Hospital physicians were less and less willing to keep long-treatable and repulsive skin and venereal diseases (for instance syphilis, scabies) in their facilities,39 even more so when it came to "lunatics."40 The doctors of the asylums did not feel responsible for "raving lunatics" and "cross-dressing lunatics." They also believed that "lunatic criminals" and "criminal lunatics" represented a threat to the admitted "curable lunatics" and the reputation of their asylum.41 The prison directors had just as little interest in this type of clientele. This attitude was only reinforced by conflicting professionalization interests of doctors, psychiatrists, and lawyers, as well as the personnel of the police and judicial authorities.42 For the afflicted, this frequently meant being shunted between institutions, in some cases for years. Their eventual escape from the hospital or insane asylum was often tolerated.

Hospitals also have a track record of locking people up involuntarily and under coercion. In this respect, the history of psychiatry is marked by problematic criteria used to classify behavioral issues as pathological, simply undesirable, or criminal. Each of these determinations could and can still lead to the concerned individuals being "locked up." Criticism of psychiatry and "anti-psychiatry" are accordingly as old as the institution of psychiatry itself.43

Forced sterilizations according to the "Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring" (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses) from July 1933 were already being carried out in hospitals as a matter of course.44 Institutional structures were ultimately also decisive for the hundreds of thousands of patients murdered by the National Socialists. The institutional conditions there were central to the murder of sick persons who had been recorded in registration forms.45 At least 31 "pediatric departments" were used for the murder of 5,000–10,000 children in the context of a "child euthanasia" program; the mass murder of more than 70,000 sick people under "Aktion T4" took place in separate extermination facilities. Furthermore, the sick were murdered in the occupied territories, concentration camps and as part of local- and "wild" euthanasia after "Aktion T4" was officially halted. These deaths also deserve attention as part of hospital history.

Health, disease, and healing

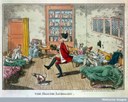

"How Howleglass, being a physician, cures all the sick in the hospital of Nuremburgh in one day"

Of all the various pranks in "Howleglass" (Till Eulenspiegel) that take place in the hospital, no. 17 of the 95 Eulenspiegel episodes46 is particularly instructive for our purposes. The prankster comes to the imperial city of Nuremberg and posts everywhere that a great physician has arrived in town. The keeper of the hospital thus calls upon him to help the 200 sick people at his institution: "And of the same sick people, the Spitelmeister would partly liked to be rid of, has deemed them healthy." In exchange for a sizeable payment, Howleglass agrees. And, in fact, he is able to help:

You know that I am come here to cure all; but, it is impossible for me to do that, without having the body of one of you to burn alive, in order to make a powder of it, which the rest are to take. The more sick and diseased the fellow is, the better he will suit my purpose, and I shall certainly choose one who cannot walk. Next Wednesday I am to come with the keeper and the governors, when I shall call over the names of all the patients, and when they must all make the best of their way out, as the last man is to be powdered for the rest." On the appointed day, the patients were all on the alert; thy had girded up their loins, and not a single one sat unbreeched, or unshod, for none wished to remain behind, either to make or to take powders. Then came Howleglass with the governors and the committee, to call over their names, but the rogues would not stop to be called: all proceeded rapidly towards the doors, even those who had been bed-ridden for the last ten years.47

In the first decades of the 16th century, the author and the readers of Eulenspiegel obviously shared the belief that hospitals had the task of housing "sick and diseased" people. In this case, it is the responsibility of the keeper of the hospital to spend money – in this story, a lot of money! – to hire a healer to heal the hospital's sick. "Illness," it becomes abundantly clear, was chiefly attributable to the fact that people were unable to leave their beds unaided.48 In this Till Eulenspiegel tale, this comes to the fore not only because we read of "sick people," but also quite figuratively. Howleglass expresses his desire to help the master of the hospital to get the sick out of bed and into a vertical position

Recovery in this sense is the obvious institutional goal of the hospital from the Middle Ages up to the present.54 That said, the means, regularity, and predictability with which this goal is achieved have changed. Put another way: what has changed is the science of healing. This change concerns not only the respective therapies and the underlying knowledge. It also involves what can be said, written, and thought about people and their physical (and mental) states between "sick" and "healthy," as well as the staff, their training, and social position.

"Here comes the wretch from his confined and dark hut ..."

Pre-modern medicine did not recognize an ideal place of recovery and healing. However, it did identify pathogenic qualities of certain places, ranging from general environmental conditions to the condition of particular rooms

like the tents in a field camp, or like the pavilions in the garden at Marly, [and] must stand apart from each other. Accordingly, one should imagine an island in the open air, in which the air surrounding the sick room would be easily set in motion by the blowing breezes from all sides, allowing the interior air to be renewed without having to move to another sick room.57

Krünitz served as a key protagonist in the European transfer of knowledge in hospital architecture thanks to extended translated quotations from the French and English debates. Friedrich Scherff excelled in a similar respect with his Archiv der medizinischen Polizei. On the heels of these doctor-led proposals for internal and external hospital architecture, the opponents of outpatient care and proponents of hospitals also presented their arguments.58 For instance, August Friedrich Hecker (1763–1811) wrote his 1793 prize-winning treatise Welches sind die bequemsten und wohlfeilsten Mittel, kranken Armen in den Städten die nöthige Hülfe zu verschaffen? ("On the most convenient and cheapest means of providing health care to the urban poor") Regarding visiting hospitals, he stated: "All these reasons are very convincing to those who have never seen in the huts of the lower classes the misery that diseases spread when they strike there."59

Hecker constructs the hospital as an ideal place in antithesis to the devastating living conditions of the poor, which were characterized by deprivation, filth, and a lack of discipline. In a similar vein, the spiritus rector of the Bamberg hospital foundation, Adalbert Friedrich Markus (Marcus) wrote:

Here the wretch comes out of his confined and dark hut ... into a spacious light dwelling; out of an unclean desert, into a house where cleanliness is the first priority; out of cooped-up, foul air, into a purer atmosphere; awaiting him here are clean comfortable garments, a soft sickbed; here he enjoys, the nourishment befitting his condition.60

It is therefore evident – including in earlier hospital histories – that a considerable part of the debate about the ideal place of healing dealt with questions of architecture and the interior and exterior furnishings of hospitals. However, it was sometimes overlooked that the questions about the construction of drainage, ventilation systems, etc. were not about "hygienic" issues in the modern (bacteriological) sense. On balance, there were still various theories about the process of "contagion" and the transmission of disease.

Yet whether the hospital – even under optimal conditions – reduced or actually increased the risk of infection, had to remain an open question at this stage. Anyone who wanted to claim the former would have done well to refer to the latest architectural techniques. On the other hand, new design could also be denounced as merely a way of concealing the actual dangers. Ernst Moritz Arndt (1769–1860) writes for example: "The rooms of the patients resemble halls in palaces, and are equipped with everything required, some things even ornamental, and for the most part you cannot tell from the air that people live here who breathe out plague, and breathe in a feverous poison."61 What's more, hospitals built according to the latest specifications were (and are) always very expensive. At the same time, the use of older buildings typically meant that the requirements – if only hypothetically – that would make a hospital preferable to a visiting institution could barely be met. In fact, the construction of completely new hospital buildings occurred only in exceptional cases

The reason why the hospital as a separate location tended to be the favored form of patient care from the 1830s and 1840s onward compared to outpatient care – at least for the sick poor – cannot be explained by the fact that it had already widely proven its worth as an independent "house of healing." Two factors were decisive for this development in Germany: First, Prussia's public health recommendations to municipalities (e.g. the 1835 Sanitätsregulativ),62 which were in the leprosy tradition, to keep isolation facilities ready for dangerous diseases. Second, there were regulations concerning the right to work for the poor and, in some cases, trade laws, which also required the municipalities to care for sick unmarried factory workers, journeymen, and apprentices.63 Thus, in the first half of the 19th century, it was only natural for the cities to establish hospitals, even if, strictly speaking, there were no medical reasons. Funding was provided by the local poor relief funds as well as by journeymen's funds and subscription schemes that allowed the better-situated middle-class households to have their domestic servants boarded there when needed in exchange for regular payments to the hospital (servants' subscriptions).64

Hospitals as privileged places of seclusion, but also of healing for the sick have therefore existed since the (late) Middle Ages. The most striking feature of these institutions is that they were not, and could not be, established – neither generally nor exclusively – on the basis of the respective medicine. This changed only with the breakthrough of modern surgery in the last quarter of the 19th century. Under the banner of asepsis and antisepsis in the surgical environment, of anesthesia and its requirements, as well as of laboratory and diagnostic technical infrastructure, the hospital only in late 19th century actually became the model of contemporary medicine. It allowed for therapeutic measures that were unthinkable anywhere else.65 A decisive for its establishment as standard medical care in the course of the 20th century was Germany's workers' health insurance, introduced in 1883. Since 1892, it had focused on the financing of medical services and was extended to salaried employees in 1911; it also provided co-insurance for family members. Besides increases in revenues and expenditures of the health insurance funds, brought about by the growing number of the insured, the average health insurance benefit per person for medical treatment also increased. It already grew threefold between 1885 and 1911. Finally, the resulting relief for the poor gave the larger municipalities (and not least church charities) the financial means to build large hospitals. The resulting care costs were then covered by the health insurance companies.

Knowledge and experience

Being poor, being sick, being cared for: the hospital as experiential setting

Reflections on the hospital as an experiential setting should start with the perspective of those who are being cared for

Concerning the patient history of the pre-modern and early-modern hospital, the most important source genre, besides the patronage contracts,68 are the applications for admittance. Even if these do not allow at first glance any immediate insight in patients experiences at hospital, they signify the applicants' emphatic desire to be admitted to a hospital.69 In this context, simulating illness and/or poverty can also be read as an active strategy directed at gaining entrance. Unlike what has typically been the case since the 20th century with a modern, fully developed hospital system, the care provided by and in a hospital until the 19th century was an out-of-the-ordinary situation that was almost always insisted on by its recipients. Accordingly, the most severe punishment of the hospital regulations was always the admonition that the diet would be reduced. Besides separate beds, which were usually provided, and the support in everyday activities, the regular diet took center stage. From benefice contracts, hospital regulations, kitchen accounting and increasingly, beginning in the 18th century, medical considerations about the "sick diet," a picture arises of the nutritional and supply situation. Care by regular and predictable feeding as given in hospitals70 has been impossible outside the hospital for considerable parts of the population. Well over one-third of the population suffered hunger in critical years of the pre-modern era.71

It would be hard to overestimate the importance of the time regiment of the pre-modern hospital for the history of everyday life and experience. Apart from common meals, the numerous prayers and other religious duties are striking. The hospital of the pre-modern period is designed as a spiritual place, as a "house of God." In contrast to directly church- or monastery-based religious spaces, hospitals also offered the infirmed or bedridden the opportunity to regularly participate in religious activities. This was done, for example, by setting up beds in the galleries of the church space or by assigning additional clergy to the infirmaries. In addition to the daily prayer duties, which in the course of the Reformation were performed as table prayers before and after meals, there were annual celebrations dedicated to the founders. On such occasions, the hospital was also visible in the city through large processions.72

The hospital foundations of the late Middle Ages and the early modern period fully reflected the social differentiation of feudal society – both at the level of the patients (through small and large, poor and gentlemen's benefices) and at the level of the hospital employees (from the hospital master to the kitchen maid). This changed in the hospital for the poor at the turn of the 19th century. In the perception of the bourgeois in particular, the hospital was known as a place of poverty and neglect, where those present "are associated with people of all kinds, mostly immoral, dissolute, accustomed to idleness, and he [the sick person] will return from the hospital after a stay of 2 to 3 months, improved in body but worsened in soul."73 In addition, a new set of patient experiences emerged in relation to spatially organized medicine in the hospital. In addition to the changed situation of the nursing staff, which was increasingly guided and dependent on doctors, the new standard was exemplified in particular by the encounter and interaction with doctors. They talked less and less with the patients about their illnesses and, if they did, it was in a language that was often no longer comprehensible to the sufferers.74 Autobiographical accounts of experiences in the hospital of the 19th century simultaneously convey the experience of a space of protection and care. The weaver's daughter Adelheid Popp (1869–1939) remarked about her hospital stay in the 1880s: "It was, as paradoxical as it may sound, the best experience I had ever had. ... I was given good food several times a day; I also often received roasted meat and stewed fruit, which I had never eaten before. I had a bed to myself and always clean laundry."75

With the institution and acceptance of the various European social security measures, the individual experience of hospitalization became common in the medium term. In the course of the 20th century, not only did birth and death in hospital become the norm, but hospitalization soon was a usual occurrence in European biographies over the rest of one's life as well. One salient trend is the constant isolation of patients by means of ever smaller rooms . The first hospital regulations of the Nuremberg municipal hospital, established in 1897, still considered "isolation in a single room" as a severe punishment on a par with diet reduction.76 An as-yet unwritten experiential history of the hospital in the 20th century could focus on the breakdown of the personal relationship between the people receiving treatment and those treating them: Hospital patients were and continue to be diagnosed, counseled, treated, anesthetized, and operated on in more and more departments and by more and more clinicians. At the same time, medical technology is playing an ever-increasing role and becoming an important power factor in the hospital, forcing both the treated and the treated into certain patterns of behavior.77 In any case, for the hospital of the 20th century, talk of a "doctor-patient relationship" between two persons is mostly theoretical.

. The first hospital regulations of the Nuremberg municipal hospital, established in 1897, still considered "isolation in a single room" as a severe punishment on a par with diet reduction.76 An as-yet unwritten experiential history of the hospital in the 20th century could focus on the breakdown of the personal relationship between the people receiving treatment and those treating them: Hospital patients were and continue to be diagnosed, counseled, treated, anesthetized, and operated on in more and more departments and by more and more clinicians. At the same time, medical technology is playing an ever-increasing role and becoming an important power factor in the hospital, forcing both the treated and the treated into certain patterns of behavior.77 In any case, for the hospital of the 20th century, talk of a "doctor-patient relationship" between two persons is mostly theoretical.

The hospital as a medical training facility

In his The Birth of the Clinic (1963), Michel Foucault analyzes the hospital as the indispensable functional-spatial condition for the ability to see and say, show and recognize, illness in the world of sick people. In a subsidiary function, the Foucauldian clinic is the ideal place of healing; but far beyond that it is the ideal place of (modern) medicine. It is the place of the "fundamental spatialization and verbalization of the pathological, where the loquacious gaze with which the doctor observes the poisonous heart of things is born and communes with itself."78 One step in this direction was the discovery of the hospital as a place of medical education.79 The university hospital in Dutch Leiden[

Adalbert Friedrich Markus (1753–1816) stated in 1790: "Hospitals are the best school for physicians. They train the apprentices to become good practicing physicians, they teach even the most skilled practitioner of the art, and bring the science of medicine to greater perfection."81 This view was quite controversial among the physicians of the time, however. Quite to the contrary, Foucault pointed out that the hospital around 1800 was "an artificial locus in which the transplanted disease runs the risk of losing its essential identity. … The natural locus of disease is the natural locus of life – the family. ... The hospital doctor sees only distorted, altered diseases."82 Alongside the hospital came treatment in the homes of the poor, accompanied by medical students, where the students "are consequently more easily and more reliably educated to their true purpose."83

Speaking in favor of hospitals was the technical-practical argument that many more diseases could be studied and compared over time. Of course, there was the possibility of performing post-mortem examinations of the deceased immediately afterwards, as well as of conducting experimental therapies.84 For good reason, printed statements did not mention the medical faculties' hope of more readily obtaining larger numbers of cadavers for anatomical studies through their own hospitals – something which had been part of the appeal of certain Italian hospitals for medicine since the mid-16th century.

In contrast to Paris and also Vienna, the establishment of university hospitals in the other German-speaking countries failed in most cases, but not only because of the lack of a well-endowed sovereign donor. The strained relationship between professors and hospital administrators, between provincial universities and municipal poor relief, between university physicians and city physicians, made it extraordinarily difficult to effectively coordinate medical education with the care of the sick and the poor until well into the 19th century. Clinical training was much easier to accomplish at non-university state hospitals such as the Berlin Charité, a clinic of the military surgical school Pépinière (literally plant nursery).85 The royal road taken by most universities in the Reich became the establishment of "polyclinic" visiting hospitals. Toward this end, Hufeland put forward some weighty arguments:

Outpatient care is the best way to train young physicians to become good practitioners and to introduce them to the public. In the hospital they only see how it should be, at the families' homes, they see how it is; in hospital they are merely educated to be artists. By visiting sick people at home they also become sensitive people, and thereby sanctify their art, and (they nourish) the sense of human love and humanity, which so easily dies out there in hospital, and interweave it most intimately with their art.86

Financed by a small budget of donations and municipal poor funds, the model consisted of a professor of medicine, accompanied by his students, treating selected (poor) patients free of charge either in their homes or, occasionally, in his own.87 The transaction between the treated and those treating them becomes especially apparent in the birthing house of the late 18th and early 19th century:88 The pregnant women were granted delivery free of charge and under certain circumstances even under preservation of their anonymity, if they were willing to let (young) men learn or practice obstetrics on them and their children. The Göttingen obstetrician Friedrich Osiander (1787–1855) spoke in 1794 of the childbearing women as "living phantoms": "The pregnant women ... are there for the sake of instruction."89 The first director of the Entbindungs-Anstalt der Königlichen Universität Erlangen, Philipp Anton Bayer (1791–1832), opened in 1827, was characteristically described as a teacher, who "crawled around for many an hour with his young friends [i.e. students] in the huts of the poor, in order to draw their attention to everything important to the physician."90 In 1801, it was still lamented that "[o]nly with much difficulty could females be obtained to be examined during pregnancy and subsequently delivered at the time of childbearing."91

In connection with his investigations on "childbed fever," Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865) moreover explained the differences between the three immediately adjacent departments of obstetrics in Vienna in the 1840s. In the "Zahlgebärabteilung," where pregnant women were delivered for a fee, there was no student teaching; in the midwifery school, midwives were taught by professors of medicine; in the department dedicated to university teaching, where obstetric care was provided free of charge, the head midwife was assisted by one or two students, who were allowed to repeat each examination on the pregnant woman as often as they wished. All the students were summoned for the bursting of the woman's amniotic sac. She was examined by five to as many as 15 students even before the delivery was finally attended to.92

Nevertheless, hospitals did not play a predominant role in the training of medical students. Most German universities, however, did start to establish small clinical institutions in the first half of the 19th century. This was sometimes accompanied – as in Berlin – by the right of "prorogation." In a municipal hospital for the poor, the sick who were of particular interest for teaching and research could be separated out from the mass of patients into academic institutions for specific purposes.93 In Germany, a deeper integration of the training of medical students with obligatory clinical training in a hospital did not occur in the course of the 19th century.94 Rather, the introduction of the "practical year" in 1901 further reinforced the separation of "theoretical" and "clinical" phases of training. In any event, the positions of municipal physician for the poor, prison doctor, or physician's assistant at a hospital were quite often a first step into the working life of physicians in the 19th century. Even more than the "practical year," specialist training from the 1920s onward, which was generally completed at appropriate hospitals, ensured that a considerable proportion of the physicians in private practice in the 20th century also received their professional socialization in hospitals.

The hospital as a site of medical research

The emphasis on the "advantages of hospitals for the state"95 – where medicine and physicians could generally be improved through meaningful training and a richer and more comparable experience – is one of the fundamental innovations of the hospital discourse of the late Enlightenment. This discourse encompassed new medical knowledge gained through experience and comparison. Inasmuch as it cannot be called experimental in the modern sense, it related to education as well as "research." A new understanding of clinical medicine emerged based on a different understanding of the relationship between knowledge and experience and which was accompanied by a qualitatively new appreciation of patient populations.96

In this context, the Hospital Vaugirard in Paris, which was founded in 1780 to treat infants with congenital syphilis, is a striking example.97 The main problem of Enlightenment-era medicine was the fact that the mercury therapy used in adults could not be readily applied to infants (or children) without endangering the patients much more than the disease or killing them altogether. The unique aspect of the treatment carried out in Vaugirard was that mothers suffering from syphilis and conventionally treated with mercury passed on the physiologically appropriate dosage of the medication to the infants with their breast milk. In this way, there were effectively turned into medical/pharmaceutical instruments.

The hospital of the early 19th century already introduced to pre-scientific medicine the tendency, spatially and socially, to cure diseases with less attention being paid to the sufferers. In a sense, these "diseases" emerged as objects of experience for medicine that were largely independent of the afflicted only under the "medical gaze" practiced in the hospital.98 While ancient medicine had already noted "pulse" and "fever" as tell-tale signs of the physical constitution of sick and healthy people, the new hospital medicine made it possible to reduce them to numerical values and developmental curves. Interpretation of the latter requires the large, uniform collection of normal values, which could only be obtained in the hospital.99 "Disease," as a defined bundle of certain physical irregularities as well as various measurable parameters, only arises against the backdrop of "normal values" from large-scale comparative observation in the hospital.

The diseases scabies and syphilis, which were considered to be "contagious" and "dangerous," attracted great interest. First of all, they were a considerable nuisance to hospital physicians. On the one hand, patients were often referred to the police in large numbers; on the other, the cure took a comparatively long time. It was above all the scabies wards that drew the most devastating criticisms from regulators. According to the physicians and the hospital journals, the illness struck socially marginalized and morally heavily stigmatized populations, especially "foreign" groups (i.e. those who moved around for a variety of reasons) such as journeymen craftsmen, along with workers and unmarried female servants. Thus there was an anxious search to shorten the treatment as much as possible. At the same time, the affected clientele often did not welcome the prospect of having to leave the hospital or for that matter the city as soon as possible.100

The transmission of disease as such was a theoretical subject of medicine. Knowledge of it held the promise of immediate therapeutic results. Of course, there were a considerable difference between treating an unexplained and extremely complex disorder of the whole human organism like "scabies" and combating an egg-laying mite. It was then asked which clinically observable manifestations, ideally classified into stages of disease progression, should be counted as "syphilis" and treated appropriately. Smallpox vaccination, still a theoretical conundrum yet widely practiced, provided the pattern for the transmission of other "disease poisons," especially syphilis secretions – this included the transfer from one person to the other and the subsequent comparative observation of clinical effects. The hospital provided the virtually helpless patients for such experiments as well as the opportunity for comparative study of the effects on larger collectives under controlled conditions.101

The clinical mode of observation is well illustrated by Ignaz Semmelweis's method. In the three departments of the obstetrics clinic in Vienna, he observed the occurrence of "childbed fever" over ten years, albeit with no identifiable patterns in terms of seasonal or climatic factors. Still, there were considerable differences in the three directly adjacent departments. When Semmelweis prescribed that everyone under examination first wash their hands with a chlorinated lime solution, he was able to dramatically reduce the incidence of "childbed fever" in the most severely affected department during the last year and a half of his investigation, if not completely. He tried to substantiate his hypothesis of the disease-causing "ptomaine poisoning" (Leichengift) experimentally on rabbits. Soon the clinical-experimental setting was repeated in Prague, however without the prescribed hand washing yielding comparable success. The ensuing criticism of Semmelweis necessarily stemmed from the experimental logic: Not only were the results not readily repeatable, but the hypothesis of ptomaine poisoning was highly flawed.102

The push to make hospital design resemble a clinical laboratory intensified with the advent of bacteriology in the latter part of the 19th century. The method and validity of scientific experiments in chemistry, biology and physics had been refined and postulated as the indispensable basis of all scientific knowledge, which now also included medicine. Furthermore, in the wake of the theoretical considerations of Jacob Henle (1809–1885) and the practical successes of Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) and Robert Koch (1843–1910), the bacteriological hypothesis of a live pathogen – as distinct from a toxin – demanded proof that it could be propagated and that subsequent generations also caused the related disease. In the hospitals and insane asylums, research-based medicine had at its disposal the similarly clueless and defenseless patients to demonstrate the disease-causing potential of the respective pathogens.103

The historical rupture between the traditional hospital and the modern Krankenhaus may be most apparent in the spatial configuration of the hospital as a clinical laboratory – as a place of knowledge and medical experience that can be objectively communicated. The earliest precursor of this nosographic (disease-describing) space is to be sought less in the hospital than medical practice journals and published case collections of the early modern period. The at times meticulously kept records of treatments and patients, prescriptions and treatment results over years and decades correspond to clinical experience far more than the patient registers of early modern hospitals, kept for administrative purposes. By means of printed medical case collections, the scope of experience expanded beyond the sum of comparable individual case histories and individual practitioner histories. In books, which were veritable printed sickrooms, it became common property of the entire reading scientific community. It was not until the end of the 18th century that hospital journals were systematically evaluated with a view to mortality and mortality rates of individual hospitals were compared internationally. In the early 19th century, "medical accounting" was still being refined. At first, such reporting was done primarily to evaluate the length of stay for certain disease groups and thus the "effectiveness" of the practice of healing from an administrative and financial point of view. The medical record eventually gave rise to an emphasis on the clinical history of illness that largely obscures the medical history of the patient. Due to the rapid specialization of clinical subjects and especially diagnostics in the second half of the 20th century, the treatment of a "case"104 by multiple physicians became the rule and the medical record the actual means of communicating about it. The "medical gaze" of the early 21st century, finally, is largely directed at the computer screen and the projection of the electronic patient record. The ideal hospital space is now a repository of data that can no longer be read without mediation.