Introduction

One standard work on the (political) history of the Balkan countries describes the region as follows:

An der Nahtstelle zweier Kontinente gelegen war die Balkanhalbinsel durch die Jahrhunderte den verschiedenartigsten äußeren Einwirkungen ausgesetzt gewesen. Sie ist als klassisches Übergangs- und Durchzugsgebiet in die Geschichte eingegangen, als eine Begegnungszone der Völker und Kulturen, an der in gleicher Weise der Okzident wie der Orient, die westlich-abendländische und die orientalische und asiatische Welt, der kontinentaleuropäische und der mediterrane Bereich Anteil haben.1

The Balkans is indeed a site of very varied cultural transfers and contacts, and with a high degree of linguistic and religious diversity. These are the result, on the one hand, of the fact that the region historically belonged to different political entities that extended far beyond the region, while, on the other hand, they are also a result of globalization and the intensive migration movements that have been a distinctive feature of this region.

But does this make the Balkans a generic border region – or was heterogeneity not always the normal condition of human social formation before the principle of the homogenous nation state became dominant? Do regions not also form border regions, even if they are not located at a physical or political border, because there are cultural and social borders within them? "Zwischen Europa und Orient" (between Europe and the Orient) is a common description of the Balkans – it is perhaps a good sign for the region that a programme with this title being funded by the Volkswagen Foundation refers to the Caucasus and Central Asia rather than the Balkans.2. Is it not primarily the location of the observer that determines what is viewed as a border region? Viewed from the Balkans, the region can appear to be at the centre of the world and the surrounding regions can be perceived as borders. What are "Europe" and "Asia" ultimately, if they are not also to a large degree heterogeneous regions with multiple connections with other parts of the world, and thus also a border? Is the state of being in-between not actually "normal", while (supposedly) clear affiliations should make us suspicious? The fact that the increasing interest of the humanities and social sciences in border regions and their cultural diversity is occurring in tandem with the waning of the master narrative of modernity and the nation suggests a non-empirical basis for the perception of spaces as border regions.

For the Balkans in particular, the question must be asked whether its conceptualization as a border region is connected with stereotypes that identify the Balkans as not entirely European and thus marginalize the region discursively. Attention has already been drawn above to the important role played by border metaphors in the cultural construction of a usually pejorative, and at best distorted image of the Balkans in western Europe (and North America) in the 19th and 20th centuries.3 Travellers who crossed the border of the Habsburg monarchy into the Ottoman Empire or Serbia often described this crossing as a step from Europe into another world with a strong Oriental influence, thus creating a border region myth. The Balkans was thus excluded discursively less as a result of ignorance than through an ontologization of marginality, of being a border region. This external attribution is so effective that it is at times reflected in the self-images of the people living in the Balkans region.4

However, to critically deconstruct the description of the Balkans as a border – particularly between such normatively loaded categories as Occident and Orient, west and east, Europe and Asia – does not mean "throwing out the baby with the bathwater". For one thing, the question arises whether the perception of a large region as a border region has heuristic potential for the understanding of areas that are generally not viewed as border regions. For another thing, the term border region can be understood in ways other than the physical geographical sense, for example, as a specific intersection between differently configured spaces of interaction and communication networks – the specifics of a region is determined by the configuration of these. Additionally, it is a historical fact that important political borders repeatedly ran through the Balkans region, which had lasting consequences for social and cultural development. To this extent, the question of the Balkans as a border region has to be expanded through the question of the borders in the Balkans.

Terminology

"Balkans" is more than a supposedly neutral name for a specific, geographically circumscribed entity. Rather, this name has a concrete history that has led to massive cultural loading. The world "Balkan" is of Turkish origin, and refers to a wooded mountain. "Balkan" was suggested as a name for a large region in 1808 by the German geographer August Zeune (1778–1853) on the basis of the erroneous assumption that the Balkan mountain range (in Greek Haemus, in Bulgarian Stara Planina) in present-day Bulgaria stretches from the Black Sea to the Adriatic, and thus encompasses a large part of the peninsula. This geographical error was soon discovered, which is why other authors suggested "southeast European peninsula" (Johann Georg von Hahn (1811–1869), 1863) and "southeast Europe" (Theobald Fischer (1846–1910), 1893) as alternatives to "Balkans" and "Balkan Peninsula".5 However, these terms were only able to establish themselves during the course of the gradual retreat of Ottoman rule. At least up to the mid-19th century, terms such as "European Turkey" were more common.

The debate about the correct name for the region was ignited by two factors. On the one hand, authors in the German-speaking territory in particular suggested "southeast Europe" as a supposedly neutral alternative to the negatively connoted "Balkan" and derivatives of it.6 In particular, the term "Balkanization", which became common after the First World War, appeared to make the term "Balkans" problematic as a name for a geographical region. However, during the Third Reich the term "southeast Europe" also experienced a politically-motivated normative loading in the context of National Socialist plans for domination ("Ergänzungsraum Südosteuropa"); research on southeast Europe in the Third Reich was implicitly a very political discipline.7 Consequently, after the Second World War the term "Balkans" was again dominant in academic literature and popular publishing in the non-German speaking world as a name for southeastern Europe. English-language survey works on the history of the region usually have the word "Balkans" in the title, even those that deal in detail with the Habsburg territories.8 However, one depiction of the history of the region in the 20th century interestingly evokes the Europeanization of the region through the terminological transition from "Balkans" into "southeastern Europe".9 In the German-speaking territory, however, Südosteuropa remained the predominant term for the region, as demonstrated by the names of the institutions dedicated to researching the region – though here too there are exceptions.10

A second fact that keeps the debate about the correct term for the region alive is the difficulty in satisfactorily defining geographically a region called "Balkans" or "southeast Europe". While seas appear to provide a clear border to the west, south and east (Adriatic Sea, Ionian Sea, Sea of Marmara, Black Sea), there is no natural border on the northern side. But even if there was one, the question would still remain whether physical borders are of particular importance for the emergence of a historical region. For these reasons, even the reference to the seas as borders is open to question.11 During the long period of Ottoman rule, for example, the Bosporus represented a connection between the European and Asiatic parts of the Ottoman Empire rather than a border, and it made more sense to write the history of these two parts together.12

A similar argument can be made with regard to the Adriatic coastal region and the Ionian Islands, which for a long time interacted more intensively with Venice (at times as part of Venetian territory) than with the internal Balkan hinterland. For the definition of a region as a meaningful historical unity of action, the question whether it is possible to identify natural boundaries is less relevant than the existence of a cluster of development strands that connect the different areas of a large region with one another and differentiate them from other regions. This does not refer to the presence or absence of a particular characteristic, but to a combination of multiple factors. An important category in this regard is historical legacy, which implies the continued influence of historical effects and processes beyond the direct context in which they emerged.13

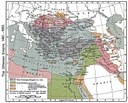

A relatively clear distinction has thus emerged at least in German-speaking academic discourse between "Balkan" and "southeast Europe". While the latter category has a broader meaning and in different contexts can also include Slovenia, Slovakia, Hungary, the Republic of Moldavia (Moldova) and parts of Ukraine – or not – the Balkans is viewed as a historical region which is characterized by a relatively clear group of characteristics that distinguishes it from other regions of Europe. Out of a range of features, I will mention only the two most important ones in the context of these efforts towards a definition: the Byzantine Orthodox Christian heritage on the one hand, and Ottoman rule and its consequences on the other hand. Defined in this way, geographically the Balkans region extends to the Sava and Danube rivers in the north, that is, to the border that was consolidated between the Habsburg and Ottoman empires in the early-18th century, or the border between the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, which remained autonomous but under Ottoman suzerainty into the 19th century, and Ottoman territory proper.14 According to this definition, the historical kingdom of Hungary (including Croatia) is not part of the Balkans, as the approximately 150 years of Ottoman rule over these territories left relatively few traces (for example due to demographic discontinuity) and the Byzantine Orthodox Christian legacy there was only peripheral.15

Historical Overview (ca. 1450–1950)

The Imperial Context

The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 was a central event for the perception of the Balkans as a border region. It was perceived by contemporaries and is still depicted in present-day history books as a watershed event, in spite of the many continuities between the Byzantine and Ottoman empires

Ottoman encroachment also created new border regions in a much narrower sense. The border between the Ottoman territory and its Christian neighbours fluctuated over a long period of time resulting in new configurations. Firstly, attention should be drawn to the Ottoman practice of settling Muslim colonists from Anatolia in the respective border region and of applying considerable force to converting Christians to Islam (though Islamicization involved extremely complex processes that are the subject of controversial academic debate up to the present; violence in the narrower sense played a subordinate role). For example, to secure the border, the Ottomans settled both Yörüks (Muslim nomads from Anatolia) and Anatolian Turks in present-day Bulgaria, which in the 14th and 15th century was a borderland before Ottoman expansion progressed further northward.18 The rapid and widespread conversion to Islam that occurred in Bosnia is probably also a result of the status of this province as a borderland, and we can assume a similar scenario for Crete after the Ottoman conquest of the island (1645–1669).19 Another special feature of Ottoman control of border regions was the practice of generally not integrating regions that were far from the capital city of Constantinople directly into the central administrative structures of the empire, but instead giving them a status similar to that of a vassal with varying degrees of internal autonomy. In southeastern Europe, this was the case with the republic of Ragusa (Dubrovnik), the principalities of Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldavia, and the khanate of Crimea.20

On the other side of the border, the neighbours of the Ottoman Empire also developed special regimes in order to strengthen and defend their borders. In the Habsburg monarchy, the institution of the military border

The Ottoman conquest of the various southeastern European states, which had formed during the Middle Ages and were more or less independent, and the advance of the Habsburgs into southeastern Europe marked the beginning of a period in the history of the Balkans that can be described as imperial, and which lasted up to the Balkans wars and the First World War. In view of the complexity of the imperial experience, it is only possible to briefly discuss some of its central elements here. It must first of all be noted that the incorporation of the Balkans into imperial contexts (this also applies to the Venetian colonial empire) brought the region into direct connection with other parts of the respective empires. For example, the military successes of the Ottomans in southeastern Europe were linked with conditions in the east of the empire, where there were regular military confrontations between the Ottomans and the Persians. At the same time, the fates of the three empires were very closely linked through wars, trade, diplomacy and other factors.23

The political development of the region was now determined to a large extent in the capital cities of the empires, which were located on the periphery (Constantinople) or outside of the Balkans (Vienna, Venice, subsequently also Budapest). This by no means meant that local elites were of no importance. The empires pursued a policy of co-opting local notables, which could quickly change to physical annihilation if the latter became disloyal. The local elites in the Ottoman imperial territories that were not directly integrated into the Ottoman administrative structures had particularly broad freedom of action, for example, the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, which had their own princes and a landowning nobility (boyars) and where the Ottoman central authorities maintained only a rudimentary presence. But even in territories that were nominally directly administered there were various separate laws, for example for population groups that performed special services for the sultan. With its conglomerate-state structure, Austria(-Hungary) was generally characterized by a decentralized structure, which only temporarily receded in favour of the central exercise of power (particularly during the period of neo-absolutism). Furthermore, in the Ottoman Empire, where recruiting was based on the principle of meritocracy, there was also the possibility that people from poor backgrounds could climb up into the administrative elite, if they were Muslim – whether through birth or through conversion – and men. A whole series of grand viziers had southern Slavic, Albanian or Greek ancestry.

The incorporation of the Balkans into the three empires was accompanied by different societal orders, though there was also a high degree of regional heterogeneity in each of the imperial structures. This was the case in particular in the Ottoman territory, not only as a result of the vast expanse of its territory, but also due to the Ottoman policy of incorporating local structures instead of changing them, and of not pursuing societal and cultural homogeneity.24 The differences in the agrarian order were fundamental in nature. Due to the central importance of land usage (the degree of urbanization of the Balkans remained very low into the 20th century), this played a decisive role in the lives of the vast majority of people. In the Habsburg territory, feudal conditions predominated except in the military border. In the territory controlled by Venice, the so-called "colonate" was dominant, a form of property ownership comparable to tenant farming. In the Ottoman Empire, in which most of the land belonged to the sultan, peasants were legally free and enjoyed hereditary usage rights to the land allocated to them.25 The very small-scale nature of Serbian and Bulgarian agriculture up until the communists assumed power after the Second World War is a direct legacy of this property system. It was a sign of the weakening power of the sultan that a form of hereditary large-scale landownership was able to emerge particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, and some peasants became economically dependent on local notables. However, latifundia of the so-called çiftlik type (Turkish for "farmstead, country estate") were not the dominant form of land usage even in the areas where they were most prevalent.26 In any case, antagonism between the sultan and local elites who were striving for autonomy was a fundamental pattern in Ottoman politics until central government gained the upper hand again during the reforms of the 19th century. In the areas of the Ottoman Balkans that were indirectly controlled from Constantinople, customary property rights prevailed, such as large-scale landownership with serfdom in the Romanian principalities and tribal joint property ownership in the mountainous regions in the western Balkans, where sheep and goat farming were the dominant forms of agriculture.

Another factor that was relevant for the societal order was the way in which the respective imperial order differentiated the population. Both in the Ottoman and the Habsburg territories, the elite was very multi-ethnic, though typically mono-confessional: Muslim in one case, Catholic in the other. While the Habsburg Empire was organized on the basis of estates until into the 19th century, the vertical social hierarchy of the Ottoman Empire exhibited a greater degree of mobility in both directions.

For societal practice, the question of the treatment of religious and linguistic diversity was particularly important, as both empires had a high degree of diversity in both regards. Though the Habsburgs viewed themselves as a champion of the Roman Catholic faith, they were prepared to make concessions to other religious communities to strengthen their rule. For example, after many Orthodox Christians (predominantly Serbs) had been settled in the Habsburg Empire after the long war against the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of the second Ottoman siege of Vienna (1683), the members of this church were allowed to establish their own bishopric with its seat in Sremski Karlovci in 1713. This metropolitanate subsequently developed into the religious and cultural centre for Orthodox Serbs. After the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Muslims were also recognized by the state as a religious community. Additionally, the southeastern European peripheries of the Habsburg Empire had a comparatively high proportion of Protestants, who had been resettled there during the re-Catholicization of the core Habsburg lands or who settled there as part of repopulation measures.27

In the Ottoman Empire, religious affiliation was a central differentiating characteristic. In accordance with the traditions of Islamic teaching on law and the state, the Ottomans understood their empire as an Islamic state (and spreading Islam as an important duty), but they granted freedom of conscience to other religions of the book (Jews and Christians). The religious communities constituted corporative groups (millet). The head of each of these negotiated with the sultan regarding the interests of the respective religious community. Each religion had internal autonomy, for example in family law.28 Of particular significance for the Balkans was the gradual inclusion of all Orthodox Christians under the authority of the patriarch of Constantinople. As the patriarchate was dominated by the wealthy, Greek-speaking merchant milieu

The role of language for the organization of the state and society and for the determination of belonging developed differently in the Ottoman and Habsburg empires. The Ottoman Empire was only a superficially bureaucratic state, in which something approaching a modern administrative system only emerged in the 19th century. The school system remained rudimentary or was left to the religious communities, and at the end of the empire only a small minority of the population had literacy skills. In these circumstances, use of the official language played less of a role in social mobility than it did in the Habsburg Empire with its considerably bigger administrative apparatus and education system. In the 19th century, the question of the official language had become one of the central political points of conflict, particularly in the multi-lingual peripheries of Austria and of Austria-Hungary after the Ausgleich of 1867

With the emergence of nationalist movements in the 19th century, the possibility of political organization outside of the imperial context began to appear. However, one would be walking into the trap of the teleological self-image, which was created by the ideological apparatus of the nation state, if one assumed a straight line of development from the first articulations of nationalist sentiment in the Balkans to the formation of independent nation states. For one thing, the understanding of the nation remained vague for a long time and its concrete content remained controversial and limited to a small social elite, while the agrarian majority usually defined itself on the basis of concepts other than "nation" even after the formation of nation states.30 Even what is now interpreted as the first nationalist rebellion (the Serbian rebellion of 1804) was precipitated by very specific local social and political problems, and was initially not directed against the rule of the sultan.

Also, nation states were not only brought into existence in the Balkans by the strength of nationalist movements; rather the politics of the European great powers, who sought to pursue their interests in the Balkans in the context of the Oriental Question, played a central role.31 Russia, as the self-appointed protector of Orthodox Christians

In the 20th century also, southeast Europe remained a region onto which European great powers not only projected their plans for rule in the region, but where they also implemented them. To this end, the great powers repeatedly tried to win over (supposedly) loyal groupings to these plans. During the Second World War, this policy manifested itself among other things in the creation of a fascist Croatian vassal state by Nazi Germany, as well as a greater Albania allied with Italy.

The Era of the Nation State

The foundation of nation states was accompanied by the drawing of new borders, both in the sense of state borders and the establishment of political and cultural boundaries. From the perspective of their understanding of themselves, the new national elites viewed state formation as a break with the imperial past, as a movement away from the supposedly Oriental Balkans and towards "Europe". However, the new borders disrupted diverse paths of communication and interaction, which had a negative effect on the economy of whole regions, for example. For the many mobile population groups of the Balkans, the new state borders represented a large obstacle, which gradual rendered their traditional way of life impossible.

The borders of affiliation were also redrawn. During the course of the late-19th century, ethnic definitions of the nation prevailed throughout southeast Europe (even though they were not the only alternative). Nationalist ideologies emphasized shared culture (as expressed in particular in the idea of a shared language) as well as shared ancestry. However, there was much more ambivalence towards emphasizing religious affiliation as a source of national identity. For example, the Albanian nationalist movement understood itself as being above confessional affiliations, in order to include Muslim, Catholic and Orthodox Albanian-speakers. For a long time, the Croatian and Serbian nationalist discourses both claimed the Muslims living in Bosnia as part of their own nation. In the case of Romania, the clergy of the Uniate church, which was strongly represented in Transylvania (with its bishop's seat in Blaj / Blasendorf), were among the pioneering thinkers of the nationalist ideology; and the Orthodox patriarchate in Constantinople understandably viewed the various nationalist movements as presenting a danger to Orthodox unity and ecumenism.32

The tension between the ethno-cultural understanding of the nation on the one hand, and linguistic and ethnic heterogeneity on the other resulted in a specific dynamic in the nationalism of southeast Europe, which continues to express itself up to the present in the ongoing processes of nation state formation

The governments of the new nation states devoted much less attention in the 19th century and the interwar period to the economic and infrastructural development of their states – which were backward by European comparison – in spite of the much cited goal of "Europeanization". The agricultural sector, which was comparatively unproductive and to a considerable extent subsistence-oriented, remained dominant. Small islands of industrialization only emerged here and there. In addition to national governments establishing priorities that were disadvantageous for economic development, the dire shortage of capital, which had already been a problem during the Ottoman period, was a central cause of the continuing under-development of the Balkans. Attempts to remedy this by raising loans in other European countries, for example, not only resulted in new political dependencies, but also repeatedly brought the Balkan countries to the brink of insolvency, or in the case of Greece in 1893 into sovereign default. Exports were generally limited to agricultural produce as well as – where they existed – raw materials. From the 19th century, dramatic import surpluses were – and are still – partially financed by considerable remittances from emigrants.33

Internal nation building thus did not occur in the form of stronger economic integration and development, but primarily through a policy of ethnic homogenization, which in times of war or during the establishment of post-war orders resulted in targeted expulsions ("ethnic cleansing").34 In the wars of independence of the 19th century, the Balkans wars (1912/1913), the two World Wars and the Yugoslavian Civil War, the conquerors repeatedly expelled members of "other" nationalities and confessions, during which Muslims suffered the most overall.35 Also of relevance for the development of international law were the instances of "voluntary" or forced population exchange between states in the context of peace treaties after the Balkans wars and the First World War. The most famous of these was the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" which was agreed between Turkey and Greece as part of the Lausanne Treaty of 1923 and which provided for the expulsion of approximately 1.5 million "orthodox Christians" from Turkey and 0.5 million "Muslims" from Greece.36 After the Second World War, there were also expulsions of population groups (e.g. the Germans expelled from Yugoslavia) and members of ethnic minorities were driven to emigration through political and social pressure (for example, the Turks who left Bulgaria in the 1950s and in 1989).37 In spite of this, southeast Europe retained a high degree of ethnic heterogeneity, partly due to the fact that there have repeatedly been phases when relatively liberal policies were pursued with regard to minorities, and because the states of the region were not always able to effectively implement assimilation programmes.

Secondly, attempts to "complete" the nationalist mission were aimed at "liberating" those presumptive members of the nation that were still living under foreign rule – regardless of which nation these people themselves identified with. During the "long" 19th century, the new nation states all pursued a policy of territorial expansion, which led to significant territorial gains, but also to bilateral conflicts (such as the Second Balkans War in 1913). The alliance configurations during the two World Wars were primarily determined by the prospects for territorial gains that the great powers offered the states of the region in return for their support during the war (in this way, for example, Romania was able to double its territory after the First World War as a result of its alliance with the Entente powers). During the Yugoslavian Civil War, it was primarily Serbia that attempted to realize plans for a greater Serbia through a policy of conquest and ethnic cleansing.38 The system of state s in southeast Europe is not recognized by everyone in the 21st century either (witness the conflict between Kosovo and Serbia, the partition of Cyprus and the secession of Transnistria from Moldova).39

Conflictual nation building and state formation were (and are) not only driven by endogenous factors. The great powers were heavily involved in the establishment of new states in the Balkans.40 Whether during the Congress of Berlin of 1878, the peace negotiations held outside Paris after the First World War, or the summit meetings between the Allies during the Second World War, in these negotiations central decisions were made regarding the political order and the borders of the region, and spheres of influence were marked out, thereby creating new antagonisms. Thus, for example, it proved impossible to establish viable cooperation between the Balkan states in the interwar period due in part to the large conflict of interests between the countries that had made gains as a result of the First World War (Yugoslavia, Romania, Greece), and those who had lost out (Hungary, Bulgaria) and were thus keen to see a revision of the settlement. After the Second World War, part of the region found itself in the Soviet sphere of influence, while Greece and Turkey were located in the "western" camp. Thus, the Iron Curtain ran through the Balkans also. Similarly, the countries of southeast Europe did not participate in the two World Wars primarily for endogenous reasons, but rather as a result of aggression from outside (Austria-Hungary against Serbia in 1914, Italy against Greece in 1940, Germany against Yugoslavia and Greece in 1941) or because the large states participating in the war forced them to join one of the sides. Thus, in the Second World War Bulgaria and Romania were on the side of Germany, on whom they had become economically dependent during the 1930s, until the invasion of the Red Army in 1944. Through this alliance, Romania hoped to get back the Bukovina and Bessarabia, which it had been forced to cede to the Soviet Union in 1941

The two World Wars were major events in the history of southeast Europe. First and foremost, there was dramatic loss of life. As a proportion of its entire population, Serbian losses in the First World War, and Yugoslavian losses in the Second World War were among the highest of any of the countries involved. During the Second World War, a large portion of the Jewish population of the Balkans fell victim to the mass murder perpetrated against that population by the National Socialists, the Croats and the Romanians. Violence was very common in territories under occupation during the World Wars. There were also epidemics (for example typhus in occupied Serbia during the First World War) and famines (for example, in Greece during the Second World War).41 In particular, the occupation policies of National Socialist Germany were characterized by exceptional brutality (for example, in the form of mass shootings of hostages and "acts of retribution" against civilians).

The two World Wars were also seminal moments in the political development of the region and had dramatic effects on the social and economic order. After the First World War, a new state came into being in the form of the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The barriers to modernization in southeast Europe were not broken down until after the Second World War, though this happened under specific political conditions that did not assist the sustainability of these modernization gains. With the exception of Greece and Turkey, communists assumed power in the countries of the region – either through a successful partisan campaign (Yugoslavia, Albania) or primarily due to Soviet support (Romania, Bulgaria). In Greece, the communists ultimately failed to seize power in a civil war that lasted until 1949. Under communist control, agriculture was collectivized (this was reversed in Yugoslavia in 1952) and there was a process of urbanization and industrialization. The infrastructure was also developed, and the level of education among the population was raised considerably.

At the same time, after the split between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union in 1948, large differences developed between the communist governed countries, which were reflected in particular in their foreign policy. Yugoslavia became one of the leaders of the non-aligned states. In the 1970s, Albania went into total isolation after turning away from the USSR and a dalliance with the People's Republic of China. From the early-1960s, Romania pursued a foreign policy that made it increasingly independent of the USSR, while Bulgaria remained one of the most loyal allies of the Soviet Union. In terms of internal politics, the differences manifested themselves among other things in a noticeably greater political and cultural liberalism in Yugoslavia, while in Albania the communist regime adhered to Stalinism practically until the end. As a genuinely federal state with six equal constituent republics that received greater rights with each constitutional reform that was conducted, Yugoslavia also differed from the other, centralist nation states of the Balkans. It is one of the tragic paradoxes of history that it was Yugoslavia, the communist regime that was the most open of all and closest to the West, that descended into a war in the 1990s that cost the lives of more than 100,000 people.43

Spaces of Communication and Interaction

Whether it was confrontations between empires on the territory of the Balkans or the establishment and shifting of borders as a result of the formation and disintegration of states, the history of the Balkans is a history of volatile borders and their varied effects on society. At the same time, these borders marked spaces of communication and interaction. Belonging to the Ottoman, Habsburg and Venetian empires meant, for example, being incorporated into an extensive geographical space of communication and interaction. This communication and interaction manifested itself in the formation of shared cultural patterns and a high degree of mobility within the respective empire. For many population groups, the empire constituted the primary framework of interaction, particularly as into the 19th century border crossings were made more difficult due to quarantine regulations. The career paths of members of the elite exhibited an amazingly high degree of social mobility.

But even outside of the elites, movement in space was no rarity. For example, it was common for travelling craftsmen from the mountains of the Ottoman Balkans to work in the Asiatic part of the Ottoman Empire, just as mobile traders, missionaries and preachers, nomads and travelling herdsmen made use of the options offered by the largely unrestricted freedom of movement within the borders of the empire. Just looking at the cityscape of southeast European cities – where the old city still survives – demonstrates that the various regions of the Balkans engaged in an intensive exchange with other regions. Architecturally, the old city centres of cities such as Sibiu

Even in the era of the nation states, the societies of the Balkans remained integrated into webs of relationships that extended far beyond their own region, even though the nation states attempted relatively successfully to condense communication and interaction within their own borders. For example, there were intellectual networks that extended beyond borders45 because a considerable portion of the first cohort of the new elites in the Balkan nation states had received their academic education in Vienna, Leipzig, Paris, Moscow or elsewhere in Europe. Spaces of communication and interaction were thus by no means only delimited by state borders. Challenges to the nation state manifested themselves in particular in former imperial border regions and in regions with a high degree of ethnic heterogeneity. The Vojvodina region in Serbian, whose political elite repeatedly sought autonomy and is still seeking it up to the present, is an example of a special regional consciousness in a border region; Istria, which experienced a strong regionalist movement in the 1990s, is another.46 In these regions, societal rejection of nationalist demands for loyalty and centralist homogenization projects was also a reaction to the painful experience of competing efforts by nation states to gain control of the region, which had the effect of introducing antagonisms into the region and exacerbated these as individual population groups were used for political purposes.

The recurring massive waves of emigration that were typical of southeast Europe even before mass emigration to America in the late-19th century also created communication and interaction contexts extending beyond the state.47 Since the Second World War, large numbers of so-called Gastarbeiter (guest workers) from Greece, Turkey and Yugoslavia have been attracted to Germany, and the collapse of the socialist state order was followed by a new, economically-motivated wave of emigration from the region involving millions of people. The communities of emigrants often continued to influence their native countries in various ways, whether through remittances or political activity. The important role of diasporas is a common theme running through nation building in southeast Europe. Whether Greeks or Bulgarians in the Russian Empire in the early-19th century, members of the Albanian minority in Italy in the 19th century, southern Slavic emigrants overseas during the First World War, Croats and Kosovans in exile after the Second World War or the Macedonia "diaspora" – these groupings repeatedly provided important conceptual and material support for nationalist movements in the Balkans, just as conversely states in the region tried to create loyal disaporas.48 The region is therefore a site of transterritorial attempts at nation building. To this extent, Balkan borders have a global continuation – while conversely global conflicts created divides and confrontations in the Balkans (e.g. during the Cold War).

Finally, the important role played by different great powers in the fate of southeast Europe is connected with the integration of the region into supra-regional networks of communication and interaction. This relates not only to the empires, but also for example to incorporation into the "West" or the "Eastern Bloc" during the Cold War, as well as the Yugoslavian special path of membership of the non-aligned movement. In particular, the integration of the region into cross-border networks manifested itself in integration into supra-regional political unions such as the European Union. Starting with Greece in 1981, a number of states of southeast Europe have become members of the EU and with it of a shared legal and economic space.49

Conclusion

Thus, the Balkans region was historically, and is also currently integrated into various supra-regional contexts, and in the present it is a very globalized region and one that is part of various transnational contexts. These interconnections bridge some of the divides within the region, while they also reinforce others. Thus, for the understanding of societal and political developments in southeast Europe, it is always necessary to determine the communication and interaction contexts a specific region or group of actors are integrated into, that is to say, where the spatial borders of the socially-relevant defining factors lie. These borders cannot be assumed, rather their significance must be empirically established.