Freemasonry and Freemasonries

There were possibly around 100,000 freemasons in 1789.1 In 1930, the Grand Orient and the Grande Loge de France together had circa 47,000, the German grand lodges roughly 70,000 and the United Grand Lodge of England about 300,000 members.2 These numbers indicate the continuing attractiveness of such forms of association for the clientele at whom they were aimed – (above all) men who were normally professionally and socially well established. Freemasonry was a Europe-wide phenomenon. Was it, then, an indicator or motor of the processes of Europeanisation between the mid-19th century and the interwar period?

As early as the 18th century, European freemasonry had already branched off into several diverse systems. A multitude of European freemasonries and systems of ritual emerged, organised along national borders. Decisive points of difference were the lodges' position on the state and politics as well as the relationship between freemasonry and religion.3 The lodges offered an alternative view of the world and kept silent about the their internal affairs. This quickly provoked resentment of freemasonry, above all from the Roman Catholic Church. "Anti-masonry" remained an undercurrent of the entire period.4 It encouraged the latent or open anti-clericalism of many freemasons.

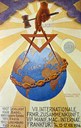

During the Enlightenment, "the self-perception of active elite circles of sages and teachers [combined] with the image of universalism, of a union of mankind across the world", of the universal masonic "chain of brotherhood".5 Cosmopolitanism became the motto of a cross-border ideology, under whose banner the freemasons hoped to rebuild the Tower of Babel in harmony and peace. Within this, a tension always existed between the universal values of the order and the obligations of individual lodge members to their country. This tension intensified according to the degree to which the structures of national (state) umbrella organisations of freemasons (the "grand lodges" or "grand orients") consolidated in the second half of the 19th century.6

In the 18th century, the universal claims of the lodges had already confronted an elite self-image or an (generally unspoken) belief in a form of "spiritual artistocracy"7 that resulted in exclusive practices. This appeared in the selective exclusion of non-Christians in general (and Jews in particular), women and – in the colonies – men not of European origins. These exclusive elements are also evident throughout the attempts to establish networks at the European, transnational level.8

The contacts between freemasons with the potential to bring about the creation of European networks possessed different degrees of magnitude and intensity. One must differentiate here between those at the individual, local and territorial or national level.9 The three levels were intertwined in that office-holders of the grand lodges were also active in local lodges, while officials from both grand lodges and lodges could take part in certain inter- or transnational forums that were not organised by grand lodges as corporate bodies. This article concentrates on the third level – the grand lodges, grand orients and supreme councils (with their officials) organised along national and territorial lines. This article understands international (masonic) relationships as being the sum total of these bilateral links. By "transnational movements and organisations", it means certain groups of masonic actors whose activity regularly spanned national boundaries and who created regulatory mechanisms for their cross-border cooperation.

Actors and Mediators

Over the 19th century, the international relationships between grand lodges formalised in that they adopted elements of interstate relationships and diplomacy. The reciprocal recognition of two grand lodges expressed itself in the establishment of official relationships with the exchange of representatives or garants d'amitié (pledges of friendship): a grand lodge chose a member of another grand lodge who would act as its representative in that lodge. These garants d'amitié regularly received the minutes of the grand lodges they represented from which they could learn about the internal situation of the lodge; they therefore had to speak the relevant language. In addition, they had to represent the concerns of their "clients" and mediate in any possible conflicts. These representatives were – alongside the grand secretary responsible for a grand lodge's entire correspondence, as well as the presiding grand master and his deputies – the human joints in the cross-border networks of a grand lodge. Numerous factors determined how these connections between grand lodges arose. On the whole, the grand lodge looking for a greater degree of acceptance took the initiative. In most cases, a supervised informal process whereby both grand lodges got to know one another's rituals, constitutions and leadership preceded the exchange of representatives.

"Natural" mediators were, for example, the members of European ruling dynasties who occupied high positions in their grand lodges. England was not the only country where close links existed between the grand lodge and the ruling house. In Prussia, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands, the ruling dynasties often provided the heads of the national masonic organisations in the 19th century.10 However, the grand lodges that included members of royal families in their ranks were the very ones that kept their distance from the internationalist branch of freemasonry. This group included only Protestant dynasties. In the European countries with Catholic royal families (Spain, Italy and Belgium), freemasons generally opposed the Catholic Church and therefore had no support among the dynasties.

Emigrants also often acted as mediators. They represented the interests of their native grand lodge in the grand lodge seeking recognition. In some European metropolises, "foreign lodges" developed that attached themselves to the grand lodges of the guest country whose rituals they practised in their own language. In London, for example, there were before the First World War two German-speaking and French-speaking lodges, as well as an Italian-speaking lodge. Their members were also natural mediators between the different masonic systems and organisations. For example, Caesar Kupferschmidt (1840–1901)11 was instrumental in laying the foundations for the establishment of relations between the United Grand Lodge of England and the Große Mutterloge des Eklektischen Freimaurerbundes based in Frankfurt am Main (the Eklektische Bund) in 1897. He was a member of the German-language Pilger lodge and was entrusted with the German correspondence of the English grand lodge.12 When in 1932 the English grand lodge revived its links to three German grand lodges severed during the First World War, two members of the Pilger and Deutschland lodges played decisive roles as mediators.13

The Creation of Networks and Camps

The international relationships and networks of European freemasonries consisted of a multitude of bilateral links between grand lodges. For example, in 1844, the Eklektische Bund only maintained official relationships with five German grand lodges and the grand lodge of New York. By 1913, the small German grand lodge had links to 17 European grand lodges and thus all the main branches of European freemasonry. At the same time, it had developed its contacts to North and South American grand lodges.14

The intensification of bilateral relationships between the grand lodges after 1850 corresponds to the general trends of inner-European and transnational networking in the second half of the century. However, one cannot see a continuous process of growth throughout the continent.15 Moreover, the bilateral relationships of the grand lodges did not create a common network in which all grand lodge officials could regularly interact with one another. Instead, each grand lodge established its own network, which only intersected with the networks of other grand lodges at a few points. Nevertheless, most grand lodges maintained indirect links to each other through their extensive correspondence and system of reporting. Using the minutes they received, the representatives of foreign grand lodges regularly had to report on the sittings of these lodges to their native grand lodge. In this way, they provided information on the external relationships of their "clients". Equally, these minutes often contained accounts of reports from other grand lodges on their external contacts, which in turn included those of yet others. A grand lodge thereby could gain an insight into the relationships of those grand lodges with whom they had no official contact. Every additional garants d'amitié thus multiplied considerably the knowledge of other grand lodges.16 However, external relations were not the first concern at the meetings of a grand lodge – finances, personnel, charity, celebrations and matters of ritual generally came first.17

From the intersections or joints of these different grand lodge networks, it is possible to construct certain geographical-territorial spaces in which one can see (at the level of the grand lodges) networks and camps within freemasonry as revealed by the international masonic congresses in the 1890s and 1900s, the Bureau international de relations maçonniques (1903–1921) and the Association maçonnique internationale (1921–1950).

The grand lodges of the Iberian peninsular, the Grand Orient de France and the Grande Loge Symbolique Ecossaise18 (which in 1896 merged with the new Grande Loge de France), as well as the Grande Oriente d'Italia, formed together with the Grand Orient de Belgique the camp of so-called "Latin" freemasonry. These lodges understood themselves as training grounds for socio-political moral concepts. For this reason, their activity concentrated on social and ideological education, and freemasons in these states took part in the various struggles against the church. The freemasons from those states in which the Roman Catholic Church occupied a less dominant position could barely comprehend this anti-clerical, activist stance. The German grand lodges split off into several camps. The liberal to agnostic tone of the "Latin" grand lodges resonated most with the "humanitarian" grand lodges which cultivated the Enlightenment ideals of religious and intellectual tolerance. Accordingly, the grand lodges of Hamburg, Frankfurt am Main and Bayreuth attended several congresses, (or at least allowed themselves to be represented). The Große Loge von Preußen genannt Royal York zur Freundschaft, the Große National-Mutterloge "Zu den drei Weltkugeln" and the Große Landesloge der Freimaurer von Deutschland, the largest of the three Prussian grand lodges, did not entirely reject bilateral relationships with the "Latin" grand lodges before the First World War;19 however, they did not undertake any international initiatives. The (Prussian) Große Landesloge understood itself to be a (de facto Protestant) Christian order, as did the grand lodges in Denmark and Sweden. The Scandinavians did establish bilateral contacts to, amongst others, the grand lodge in Frankfurt and the Grande Oriente d'Italia.20 Despite this, they did not participate in international initiatives either. This was true after the First World War of the German "regular" grand lodges in general.

The Grand Orient of the Netherlands and the Swiss grand lodge Alpina occupied a midway position between the "Latin" and German freemasonries.21 Alpina had a reconciliatory and mediatory impact through its extensive links to all the camps of freemasonry in Europe, not least because it had already brought together the smaller lodges within Switzerland that used French-, Italian- and German-language rituals. In the 1890s and 1900s, Alpina was the real pacemaker of the transnational grand lodge movement. Throughout the entire period, however, it failed to bring the freemasonries of the British Isles closer to those on continental Europe. There were three grand lodges in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (in England, Scotland and Ireland) and three supreme councils of the . While the three grand lodges at least maintained bilateral links to a few continental European grand lodges, in particular those in Scandinavia – the Irish even doing so with the Italian grand orient –, they kept their distance from all international initiatives.

Therefore, the creation of European networks, which consolidated into transnational movements, was mainly a phenomenon of west and southwest European freemasonries, albeit with a slight German flavour. Involved, too, were the Symbolic Grand Lodge of Hungary (founded in 1886), which took part in all international congresses between 1889 and 1911, the Grand Orient of Turkey (established in 1909) and the National Grand Lodge of Rumania (founded in 1880; present in 1896, 1904 and 1910). Geographical gaps can sometimes be explained by the state framework: while lodges were founded clandestinely in states where freemasonry was forbidden or not officially permitted, these could not create grand lodges recognised by the state and acquire international representation. For example, the Hungarian grand lodge could only emerge after the Austro-Hungarian Ausgleich of 1867 that granted the Kingdom of Hungary partial autonomy. In Austria, a grand lodge could only appear after 1918 (as the Grand Lodge of Vienna); it started taking part in international initiatives in 1921. Similarly, in Russia and Russian-ruled "Congress Poland" individual lodges were founded. However, before the world war, these were unable to organise into grand lodges and thereby create international networks.

An intrinsically transnational system of freemasonry was the Ancient and Accepted (Scottish) Rite (A.A.[S.]R.), distinguished through its organisation into 33 degrees.22 It built upon the national principle in that in every state there could only be one "supreme council" to supervise all the local bodies on the state's territory. The supreme councils were connected to one another via specific structures of communication, and the spread of the Scottish rite in Europe23 reveals networks within which different camps also emerged. The supreme councils of the rite first appeared in the "Latin" countries (France in 1804,24 Spain in 1811, Belgium in 1817, Portugal in 1842/1869, Italy in 1887 [the year of the unification of three supreme councils],25 Switzerland in 1873 and the Netherlands in 1913). In addition, supreme councils emerged in Hungary (1871), Greece (1872), Turkey (1909), Serbia (1912), Poland (1922), Czechoslovakia (1922) and Rumania (1923). The rite also established a foothold on the British Isles (Ireland in 1826, England in 1845 and Scotland in 1846). Although the British grand lodges there officially ignored the supreme councils, in practice there were numerous personal interconnections. In contrast, the grand lodges of Denmark, Sweden and Norway did not tolerate alternatives to the order's ten-degree system in their "dominion". Scandinavia remained closed to the networks of the Scottish Rite, as did Germany, where a supreme council only appeared in 1930. Therefore, the European map of the Scottish Rite displayed – with the exception of the British Isles – the same empty spaces as that of the international networks of the grand lodges.

Deepening and Consolidation

Although the informal and official relations between the grand lodges deepened in the second half of the 19th century, these networks only consolidated slowly and incompletely. Around the middle of the century, there were two initial attempts to increase international cooperation. An early gathering of German, French and Swiss lodge members in Strasbourg (1846)

1899 introduced a new dynamic when the Grand Orient de France convened an international masonic congress of freemasonry to celebrate the centenary of the French Revolution.28 Congresses with representatives from grand lodges followed in Antwerp (1894), The Hague (1896), again in Paris (1900) and Geneva (1902).29 The latter decided to found a Bureau international de relations maçonniques30 (BIRM), which indeed took place in the following year. This was headed by Edouard Quartier-la-Tente (1855–1924, who served as the Alpina grand master, 1900–1905)

Before the First World War, the supreme councils of the Ancient and Accepted (Scottish) Rite were also occasionally represented in the international congresses of freemasonry alongside the grand lodges and grand orients. This was particularly true of countries in which the grand lodge(s) did not compete with the supreme council.

A grassroots movements of individual freemasons ran parallel to these transnational formations at the level of the national grand lodges.37 It originated in the German-French-Luxembourgian border area. By around 1900 – a generation after the 1870/1871 war –, memories of the conflict and the attendant hostility were beginning to fade. In July 1907, after reciprocal visits to lodges, 400 predominantly French and German freemasons met for a "brotherly gathering" in the Vosges mountains for the first time. They swore to continue meeting every year at a different location. Until 1913, they were able to carry out this voluntary obligation (except for 1910);38 the outbreak of war prevented the meeting planned for August 1914 in Frankfurt am Main

The organisational committee remained Germano-French at its core. Later peace manifestations – in Paris (1911), Luxembourg (1912) and The Hague (1913) – indicate, however, geographical expansion with regard to both location and participants. It was interwoven into the congress movement of the grand lodges and the BIRM through numerous personal relationships. These had an institutional impact in that – due to the lack of other opportunities – meetings of the grand lodges in the BIRM took place on the fringes of the manifestations. Because the institutionalisation of the Bureau came to a halt after 1904 and it could not cope with the organisation of international congresses, the peace manifestations – above all those between 1911 and 1913 – represented to a degree an alternative forum to the congresses, which were experiencing a hiatus after 1911. Accordingly, while the independent organisational committee made the preparations for the peace manifestation of 1913 in The Hague, the Grand Orient of the Netherlands accommodated it. Therefore, the freemasons' peace manifestations before the world war were in a sense developing into a transnational movement within western continental Europe (with the exception of the Iberian peninsular).

During the war, an international conference that crossed the conflict's political divisions was unthinkable. Instead, the Grand Orient de France convened a congress of freemasonries of the allied nations in Paris for January 1917. The representatives of the grand lodges sent fraternal greetings to the freemasons in the USA, condemned German war crimes and proclaimed the right to national self-determination of the small nationalities, above all those in the Habsburg Monarchy. They called upon the freemasonries in neutral states to participate in another congress (in Paris, June 1917). This would discuss an action plan regarding the foundation of a League of Nations.42 The United Grand Lodge of England did not take part in either congress due to a schism within freemasonry. As a kind of counter-event, in the same year, it organised bicentennial celebrations for the foundation of the first grand lodge in London in June 1717. Thousands of freemasons took part in the festivities and concluding service in the Royal Albert Hall, including representatives of numerous grand lodges from the British Empire and the USA.43

Following the world war, a transnational movement began, once more, to develop at the grand lodge level. Grand lodges from the "Latin" camp were again predominantly the driving force. It had become clear that a single office was not sufficient to provide the foundation for an international organisation. In 1921, the one-man endeavour of the BIRM was replaced by the Association maçonnique internationale (A.M.I.) at an international congress in Geneva.

After 1918, new initiatives directed at individual freemasons complemented those of the grand lodge movement as institutionalised in the A.M.I.. A circle of masonic Esperanto-speakers had founded an Esperanto Framasona Ligo in 1905. In 1913, this was renamed at the Universala Framasona Ligo. This only included individual members regardless of their grand lodge membership. In 1926, it was reorganised into the Allgemeine Freimaurer-Liga (Ligue internationale de francs-maçons, A.F.L.).47 From then on, it was arranged into national and professional groups. The members met at international conferences, whose proceedings appeared in their own periodicals.48 In order to advance their ideal of universal peace and harmony, the European leadership of the league particularly sought to attract members from the USA. Before the Great Depression, they were quite successful. One thousand freemasons took part in the Viennese congress of 1928.49 Thereafter, the meetings became increasingly European. The gathering planned for 1932 in Berlin did not take place because the non-German freemasons expressed reservations following rioting in the Nazi capital.50 The league's meetings continued until the 1939 Amsterdam conference.

The international masonic manifestations for peace were also revived after the First World War. The two new transnational masonic organisations (the A.M.I. and the A.F.L.) sought to make use of this "brand": after members of the manifestations' old organisational committee had proclaimed the first post-war meeting for August 1926 in Basel, the grand lodge "Yugoslavia" in Belgrade organised a further peace manifestation with representatives from grand lodges under the aegis of the A.M.I.51 In addition, the congress of the A.F.L. in Basel (October 1927) initially worked under the name 8e manifestation maçonnique internationale. Following protests from the old organisational committee, the peace manifestations continued with a 1928 meeting in Verdun, without any ties to the two transnational organisations.52 The gathering of 1929 in Mannheim discussed, amongst other issues, the Briand Plan and the Pan-European concept of the (freemason) Richard Nikolaus von Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894–1972)[![Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894–1972) Schwarz-weiß Photographie, o. J. [vor oder 1936], unbekannter Photograph; Bildquelle: Coudenhove-Kalergi, Richard: Europa ohne Elend: Ausgewählte Reden von R. N. Coudehove-Kalergi, Wien 1936.](./illustrationen/europa-netzwerke-bilderordner/richard-coudenhove-kalergi-189420131972/@@images/image/thumb)

Motives and Motivations

The congresses of the grand lodges, the BIRM and the A.M.I., as well as the peace manifestations and the A.F.L., were facilitated by the creation of networks within European freemasonry and created new networks among freemasons. At the same time, one must see them in the context of external processes of internationalisation in the academic, economic, artistic and socio-political realms, the forums of which (above all international congresses and transnational journals) the freemasons adopted no less than the consciousness of a general process of globalisation which the brotherhood should follow.

All forms of communication and networking with foreign "brothers" and grand lodges could be justified by freemasonry's idea of universal brotherhood. Like the explicitly expressed motivations for this communication, the implicit motives, based on partially hidden interests, were emphasised differently depending on the form, depth and extent of the various networks. However, various recurring patterns of justification are evident that explain why and how the 18th-century masonic tradition of cosmopolitanism could be transformed into an organisationally tangible "chain of international brotherhood".

One major impulse for the individual grand lodges to create denser networks of relationships using bilateral links to other grand lodges emanated from the desire for closer "fraternal" communication and new ritual experiences. Participation in the masonic ceremonies practised by other systems of lodges could help one to understand better the particularities of one's own rituals (procedures, dialogues and the interpretation of symbols). Often, however, it was mainly the representatives of the foreign grand lodges who explored this area in depth. For the leadership of the grand lodges, tangible interests augmented the ethical motivations.

Amongst freemasons, the aim was often to confirm one's own masonic legitimacy through broad recognition from abroad. This desire was based on a historical/genealogical understanding of masonic "regularity" that emanated from the foundation and family tree of a lodge or grand lodge. The desired increase in legitimacy through international recognition was frequently directed against competing grand lodges within the same state; those grand lodges looking for contacts were often "new" bodies that found themselves in the position of dissidents or a minority vis-à-vis the established grand lodge. In other cases, the aim was to consolidate or improve one's position against rival grand lodges in those zones of influence that had not yet stabilised, both within Europe (for example, in the states that appeared on the territory of the Habsburg Monarchy after 1918) and outside it (in colonies and protectorates). Within society, close relationships with foreign freemasons promised to strengthen grand lodges against domestic rival or hostile groups and currents (i.e. anti-masonry). In turn, grand lodges in countries where anti-masonic voices and movements were relatively weak had little need for international solidarity (for example, in Prussia, Scandinavia and the British Isles).

By becoming involved in the congress movement of the 1890s, the BIRM and, later, the A.M.I., grand lodges signed up to the idea of putting the "chain of international brotherhood" and freemasonry's claim to universality into practice. They also saw the promotion of understanding between freemasons in different countries as an active contribution to peace and a masonic branch (and vanguard) of the peace movement. They attributed an inherent value to international meetings and congresses: in a symbolically experienced fellowship that disregarded national, religious/confessional or other group identities, freemasons believed they could advance international understanding. The involvement of many transnationally active brother freemasons in masonic organisations that promoted peace and international understanding in the broadest sense corresponded to this – for example, the Fédération internationale maçonnique pour la Société des Nations and the Fraternité – Réconciliation. Groupe pour le rapprochement franco-allemand (hosted by the Grand Orient and the Grande Loge de France), which merged in 1930. Freemasons worked in "profane" pacifist and internationalist organisations, such as the Ligue Internationale de la Paix et de la Liberté, the Association internationale pour le progrès des sciences sociales, the Association pour le droit international or the Bureau International pour la Paix. The intersections between freemasonry and the general peace movement need further study.55 Here, one must always distinguish whether individuals who happened to be freemasons took part56 or whether lodges, grand lodges or transnational organisations provided institutional support. These acts of institutional cooperation certainly existed between individual grand lodges and international associations of freethinkers; thus, the Grande Oriente d'Italia committed itself to the Associazione nazionale del libero pensiero "Giordano Bruno" for several years.

This indicates a further motivation for the grand lodges' international networking and transnational activity – the reaction to and the defence against anti-masonic attacks. The "Latin" freemasons' anti-clericalism, which at the transnational level was both an inclusive and exclusive factor, was also a response to the rise in anti-masonry after 1900, which had similarly created its own national and international networks.

Conflict, Oppositions, Fissures

In December 1913, the United Grand Lodge of England recognised a French grand lodge created under the name Grande Loge Nationale Indépendante et Régulière pour la France et les Colonies. This new grand lodge had drawn up with London's informal collaboration a list of criteria for its daughter lodges: during all masonic ceremonies, the bible should lie on the altar; during the opening and closing of the lodge, one should call upon the Great Architect of the Universe; no political or religious discussion should be permitted in the lodges; all members enjoyed freedom of thought and action, but the lodges should not become involved in political affairs; only freemasons recognised by the English grand lodge as "true Brethren" could join; the rite followed the Régime Écossais Rectifié of 1778 into which the Duke of Kent had been initiated in 1792.57

From the English perspective, a French umbrella organisation had finally emerged from the Grand Orient de France that could be viewed as regular according to London's criteria. This followed a 35-year ice age between the English and French freemasons that had arisen when the Grand Orient discharged its lodges of the obligation to employ a symbol of the supreme being when accepting new members in 1877. The Belgian grand orient had already undertaken this step in 1871. The English grand lodge broke off contact with both it and the Grand Orient de France in 1878 and threatened to withhold its recognition from all grand lodges that maintained contact to them. The foundation of the Grande Loge de France (1895) did not restore masonic ties between the two countries because it had been initiated by the French Suprême Conseil, which the English did not recognise either. The split grew into a European schism. Every grand lodge had to decide if it wanted to lose its "regularity" according to the London interpretation if they sought or maintained contact with the Grand Orient de France.58

A parallel development in the international relations of the supreme councils of the Ancient and Accepted (Scottish) Rite is also evident: in 1881, the supreme council of England and Wales left the international confederation of supreme councils that had only recently been created in Lausanne in 1875. Like the Scottish and Irish councils, the English insisted on its "Christian" tradition and refused to fraternise with such "irregular" bodies that preferred an impersonal definition of the supreme being. The three British supreme councils did not take part in any of the subsequent conferences of the rite.59

The recognition of the new French grand lodge in 1913, which itself had no links to the country's two older grand lodges until the 1950s, is an example of the English claim, based on their position as successor to the world's first grand lodge created in London in 1717, to represent the "mother lodge" of international freemasonry and its belief in the universal applicability of its principles. At the same time, in 1913, one can see the central areas of conflict within the bilateral relations of the European grand lodges which now moved onto the transnational level.

These conflicts were normally fought out within the code of masonic "regularity", which contained various formal and intellectual/ideological criteria for recognition, which could be realigned and applied to rival or "disruptive" grand lodges according to current interests.60 The verdict "irregular" often did not require justification because, on the whole, the onus of proof was on the grand lodge branded in this way to demonstrate its regularity itself. For example, most of the German grand lodges (which defined themselves as "regular") prohibited their members from joining the Allgemeine Freimaurer-Liga because "irregular" masons also belonged to it.61 Due to the multitude of lodge systems and their countless rivalries, it was impossible that the A.F.L. could only include members from grand lodges recognised by all the others.

Within the A.M.I., too, long-lasting conflicts broke out over the membership of "regular" or "irregular" grand lodges. The association decided to leave it up to its member grand lodges whether or not they maintained links with each other. This construction enabled both "regular" and "non-regular" grand lodges to remain members. It, however, only superficially defused the arguments over criteria while underminig the goal of unification that had underlain the creation of the A.M.I. A grand lodge that wanted to join did not even have to subscribe to the founding proclamation.62 This compromise from 1927 was intended to encourage more grand lodges to join. However, it actually limited the organisation's perspectives to develop its internal coherence, binding authority and ability to achieve its aims.

At both the national and transnational levels, the question of territoriality was an important element of the (ostensibly) formal criteria of recognition. The principle of "territoriality" underpinned a grand lodge's claim to have the exclusive right to found daughter lodges within the territory of a certain state. There was debate on whether this restriction was only for the first three masonic degrees or for the appendant masonic orders and systems of degree. None other than the grand lodge of London insisted on recognising only one grand lodge in each country. In most countries, however, two or more grand lodges competed with one another – in Prussia alone there were three grand lodges, in the rest of the German Confederation, and later German Empire, at least five more. The English also cited the principle of territoriality in their opposition to other European grand lodges founding daughter lodges in the oversees parts of the British Empire. The principle of territoriality was one of the reasons for the grand lodge of New York turning its back on the A.M.I.63

The most controversial intellectual/ideological question was the religious nature of freemasonry and the religious commitment of individual lodge members. This had provoked the Anglo-French schism of 1878 and fuelled the conflicts over regularity within the A.M.I. The Dutch grand orient left the organisation primarily because of the lack of a clear declaration of belief by the participating grand lodges and their members in a supreme being. The Spanish, French, Belgian and Italian grand lodges, which to differing degrees contained agnostic, scientistic and sometimes atheist currents, viewed this as a violation of the individual's freedom of conscience. Within the grand lodges that set religious belief as a prerequisite for freemasonry, there was a debate on whether the masonic postulate of tolerance, which in the first constitution of 1723 was limited to members of Christian confessions (in early 18th-century England, this was already a generous provision), should be extended to members of other religions. In central and western Europe, the main question was the admission of Jewish applicants.64 The so-called "Christian principle" divided the Scandinavian and Prussian national lodges, which understood themselves as Christian orders, from the spiritual and deist British lodges. German freemasons who defined themselves as "humanitarian" inclined more towards the latter. However, even among the "humanitarian" grand lodges, the formal admission of Jews (in the statutes) and local practice regarding admittance diverged. This fundamental question put a strain on international masonic relations within the entire period under discussion.65

The Christian and spiritual/deist camp were united in rejecting religious and political discussions within the lodges and opposing the adoption of positions or involvement in socio-political matters by the grand lodges and lodges. The London grand lodge believed that the French grand lodges contradicted the nature of freemasonry when they discussed in advance draft laws on education policy from which masonic parliamentary deputies received ideas. Equally, it condemned the Grande Oriente d'Italia's advocacy of certain candidates in local elections. The activist grand lodges of the "Latin" camp also regularly quoted the Charges of 1723, which they believed did not prohibit the discussion of political questions in general, but rather "quarrels" over such issues so as not to disturb harmony during and after the masonic ceremonies.66 Masonic charity seemed, in contrast, to be apolitical. The English grand lodge, in particular, carried out charitable work extensively and not only for lodge members and their families. However, because this charity aimed to alleviate the deleterious by-products of industrialisation and thus prevent social unrest, it had an implicit socio-political dimension.

These internal antagonisms were overlaid by conflicts that crossed over from the political sphere into freemasonry. The most important referred to the relationship between the state and the (Catholic) church, whereby the anti-masonic element in states dominated by Roman Catholicism was mirrored in an equal level of masonic anti-clericalism. In addition, throughout this period, the confrontations between the European nation states acquired increasing importance. The 1870/1871 war had made bilateral communication between French and German freemasons all but impossible for three decades. This affected international masonic relationships in Europe in general. Massive resentment accompanied the Franco-German masonic gatherings before 1914, as was the establishment of relations between the Grande Loge de France and the German grand lodges in 1907.67 During the First World War, the tentatively emerging masonic transnationalism collided with political and state confrontations that did always not correspond to the networks and camps that had developed. The grand lodges in the states of the Central Powers and the Entente broke off contact with one another. The participants in the Paris congress of 1917 and the bicentennial celebration of the English grand lodge in the same year did not attempt to formulate a neutral position for universal freemasonry that stood above all national parties.

These constellations shaped the post-war period. The grand lodges of the former Entente and neutral states, above all the Belgian grand orient, demanded that the German grand lodges unreservedly acknowledge responsibility for German war crimes against Belgian civilians. The Germans, in turn, linked the resumption of relations with the French to the removal of the articles in the Treaty of Versailles which apportioned sole liability to Germany for the war.68 Like mainstream German society in general, the German grand lodges saw a compromise with the victorious powers without any revision of the Versailles treaty as treason. In addition, they did not want to fuel the conspiracy theorists searching for a scapegoat for the defeat, who sought to brand all "freemasons and Jews" as traitors to the fatherland. The shift within anti-masonry from clerical/church to nationalist/totalitarian and sometimes racial ("völkische") concepts, which had begun at the end of the 19th century, grew stronger after 1918, and this had an impact upon the confrontations between the European grand lodges. Thereafter, international meetings and even transnational organisations were a highly politicised matter in all masonic camps regardless of the topics discussed at them. This polarisation put pressure upon the A.M.I. from the very beginning.

Throughout the entire period, the basic mindset of the leadership of some lodges and grand lodges presented international initiatives and transnational movements with a considerable obstacle. Such people considered an organisational consolidation of the "chain of international brotherhood" unnecessary because every individual freemason regularly practised the idea of belonging to a worldwide fraternity through the ritual ceremonies in his local lodge without having to "physically" create it.69

Implementation

Due to these conflicts and competing camps, it is hardly surprising that the attempt to build a transnational movement on the basis of cross-border networks failed to meet expectations of those involved, with regard to their impact both within freemasonry and outside. Those who discussed implementing the utopia of worldwide brotherhood and universal peace could not avoid the controversies surrounding ideological and political questions. This could, in turn, be rejected as "un-masonic" or a threat to the essence of freemasonry. In particular, it was impossible to achieve agreement on the question of the goals and methods of masonic activity outside the ritual lodge ceremonies. A "masonic international" conducting coordinated campaigns, both in secret and in the open, only existed in the imaginations of conspiracy theorists and opponents of freemasonry.70 Cross-border masonic networks could only emerge sporadically, generally in certain specific national contexts. This activity rarely went beyond declarations of solidarity. Three examples will underline this claim.

The most enigmatic figure of Italian freemasonry was Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), who was condemned by the Inquisition and burned in Rome. Bruno became a symbol of free thought and anti-clericalism. Consequently, Italian masons honoured him in the 19th and early 20th centuries as a freemason avant la lettre. The allusion to Giordano Bruno placed the Grand Oriente within a network of bourgeois-liberal and progressive-freethinking organisations and parties. Bruno provided the grand orient with a figurehead whose mission it could universalise by invoking his spirit in the fight against the intolerance of the "universal" church. What could be more obvious, then, than raising him to a patron of the massoneria universale? At first glance, the Bruno cult really did have a European dimension (which, indeed, extended further than the continent). He had stood for the universal ideal of freedom of conscience and thought; his curriculum vitae was "European" par excellence (Bruno had fled from Italy to Switzerland, France, England and Germany). This appeal is evident in the celebrations surrounding the dedication of the memorial to Giordano Bruno on the Campo de' Fiori in Rome in 1889.

A further event of pan-European significance was the execution of the Spanish freemason and libertarian pedagogue Francisco Ferrer (1859–1909)[

The support given by individual freemasons, grand lodges and transnational organisations to the League of Nations in the 1920s went beyond mere declarations of solidarity. Particularly active were the Grand Orient and the Grande Lodge de France, which provided the foundations for the activity of the Fédération internationale maçonnique pour la Société des Nations. In 1924, the Grand Orient invited its daughter lodges to consider the League of Nations from a historical perspective and to tie this to the discussion of Franco-Soviet rapprochement and the resumption of Germano-French relations.73 These moves influenced the creation of the A.M.I., which was structured according to the pattern of the League of Nations and similarly had its headquarters in Geneva. The Brussels convention of the association in 1924 called upon all freemasons throughout the world to support the League's attempts to promote peace.74 Consequently, the disappointment at its limited capacity to act was considerable. The A.F.L. also addressed the political objectives and situation of the League of Nations, issuing several resolutions to the governments of the member states.75

The extent to which this "lobbying" had a measureable impact beyond the sphere of masonic activity is difficult to judge. At the inter- and transnational level in particular, masonic "campaigns" were primarily theoretical works, first and foremost directed at freemasons themselves as part of the comprehensive education of the individual mason. In the end, this was also true of the grand lodges that sought to develop a socio-political profile.

Europeanisation?

The institutionalised version of masonic inter- or transnationalism could never realise the universal claims of worldwide fraternity. From the 1920s and 1930s, the prohibitions on masonic organisations in Europe's authoritarian and totalitarian states76 combined with the conflicts between nation states shattered the ambitious European transnational aspirations. masonic transnational movements and organisations did not per se limit their pretence to authority geographically, seeing it instead as "universal". To concentrate explicitly on Europe therefore contradicted both their intellectual/universalist and their activist/internationalist goals. In practice, however, freemasons and grand lodges from western and southwestern continental Europe organised and funded the congresses of the 1890s and the 1900s, the BIRM and the A.M.I., as well as the A.F.L. and the masonic peace manifestations. When one looks at the locations for the international meetings, one sees a masonic "core Europe" (albeit including Switzerland) which – without implying any causality – recalls the Europeanisation processes of the 1950s: between 1889 and 1936, the masons met in, for instance, Paris, Strasbourg, Antwerp, Brussels, Luxemburg, Amsterdam, The Hague, Geneva, Basel, Bern and Rome.77 With a few exceptions, this was also true of the individual protagonists of the movement. Pragmatic reasons partially explain the concentration within this space – it was too inconvenient for the majority of grand lodges to travel to the Iberian peninsular, for example. However, it is also an indication of the fact that the (initially) bilateral networks and the transnational movements and organisations that built upon them could either promote or mirror Europeanisation processes.

Between 1844 and 1932, the Große Mutterloge des eklektischen Freimaurerbundes had at least 117 members within it acting as the representatives of 37 European grand lodges. In return, 117 freemasons were appointed to represent the Frankfurt grand lodge in these 37 European grand lodges in the same period.78 If one tentatively assumes that all the grand lodges had links with grand lodges and supreme councils via the same number of representatives, then between 1850 and 1930 there would have been about 8,700 freemasons acting as the representatives of European grand lodges. When one compares this transnational elite with the absolute numbers of members, for example the 57,000 freemasons registered with the Grande Oriente d'Italia between 1880 and 192379 or indeed the 300,000 members boasted by the United Grand Lodge of England in 1930 alone, then this number is tiny.

However, the representatives belonged to the broader circle of leadership within the grand lodges and helped determine their policy. They thereby belonged to the leading echelons of European freemasonry. They regularly had to deal with the correspondence and minutes of their respective partner organisations, which, in turn, contained the reports of other grand lodges. They represented the institutional bonds within European freemasonry, despite the fact that they generally only engaged in written communication with their partners. However, the 460 individuals, representing 83 European grand lodges (some of them short-lived), who took part in the 16 international congresses between 1855 and 1932 invested these bonds with life. Here, they could establish personal relationships with other delegates. More significant in terms of shear numbers than the grand lodge congresses were the international peace manifestations and the conferences of the Allgemeinen Freimaurer-Liga; several hundred to a thousand freemasons gathered to attend such events. Despite the various camps and dividing lines, these participants embodied the "lived" "Europe of freemasons".80 The drive towards Europeanisation within freemasonry, promoted by the intensification of bilateral relationships and, above all, the congress movement from the 1890s, should not be underestimated, although one cannot currently quantify it or compare it to other movements. The question of whether the Europe-wide networks created by the visits of individual masons, the exchange of representatives between grand lodges, international conferences and transnational organisations had an impact on freemasons' consciousness of Europe, i.e. the "imagined" Europe, is another story.81