Introduction

"Theological Networks" refers here to the web of interrelationships which developed within the Orthodox church between 1450 and 1950. These networks facilitated or, in some cases, hindered the transmission of theological contents or attitudes.1 Orthodoxy initially primarily denoted those Christians in communion with Constantinople who are nowadays called Eastern Orthodox Christians.2 This article is not about their theology as such, but about infrastructures which enabled this theology to become what it had become by the 1950s.

The following examples illustrate the evolution of the technological infrastructure between the terminus a quo and the terminus ad quem. News of the fall of Constantinople

One need only note the importance which the printing of Bibles, liturgical books, and "forbidden works" has in Orthodoxy to note the difference in publication modalities over time. Patriarch Kyrillos Loukaris' (1572–1638)[

Frameworks for Networking: Iconic Consciousness as an Example of a Changed Paradigm

Although a detective story becomes less interesting once the end is known, having such knowledge at the start provides more clarity in following up ideas. Nowadays, a common way of understanding the clash of ideas both within Orthodoxy and between Eastern and Western Christians is to look for "the non-theological factors".6 It is typical of our times that we tend to reduce theological differences to non-theological ones; thus theological differences are reduced to a pure clash of neutral ideas which do not compromise salvation, etc. The culture is blamed, not a different approach to Christ or to salvation. An example of this mediating factor between theological ideas is the switch in iconic consciousness in our period. The icon is a particularly subtle indicator, because here theological and non-theological factors are intertwined. Curiosity is activated, but not only aesthetic questions are at stake. The icon is thus an extremely important object, because, according to St. John of Damascus (ca. 675–ca. 749), it stands for the very incarnation of God.

Whereas in Western Europe the loss of iconic consciousness is usually connected with the influence of the young painter Raphael (1483–1520), the date for Russia is set at the time of the death of the icon-painter Simon Ushakov (1626–1686), not only because the naturalistic perspective of Renaissance art came to predominate in the East itself. Rather, an index of the retrieval of genuine Eastern iconicity begins with Nikolaj S. Leskov's (1831–1895) story Zapechatlennyi angel (The Sealed Angel, 1873) which credits Old Believers with preserving Orthodox tradition better than the Orthodox Church itself.7 Close as he was to Lev N. Tolstoy (1828–1910), Leskov estimated that the sectarians preserved the traditional canon of the icon better than the official Orthodox Church. Here, Fr. Georges Florovsky's (1893–1979) theory of the malformation, or pseudomorphosis, of post-Reformation Orthodox theology is shown to be right, however open it may be to criticism when generalising on all aspects of post-Reformation life in Orthodoxy.8

The gradual disfiguration of the traditional icon in the official Orthodox Church, which increasingly copied the Western Renaissance canon of plausibility rather than inviting the beholder to enter God's transfigured world, was just one example of this pseudomorphosis. Only in the last 60 years of our period have masterpieces such as Andrej Rublev's (ca. 1360–ca. 1430) icons and frescoes been restored, paving the way for the icon's triumphant conquest of the Western art world.9 Icons themselves are not simply intermediaries between ideas, they are also the hallmark of an age fraught with a theologically complex agenda, with practical and theoretical consequences. Dionysius of Fourna's (ca. 1670–ca. 1745) Hermeneia (Painter's Manual, ca. 1730),10 composed on Mount Athos, may be considered a desperate effort to safeguard tradition, but according to Photios Kontoglou (ca. 1895–1965), it was an attempt to retrieve the rationale behind so much questioning of traditional forms.11

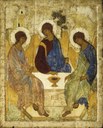

After the so-called Triumph of Orthodoxy over Iconoclasm (843), icons became a criterion of Orthodoxy.12 They are called canonical if they reflect official Church teaching. For example, under Ivan IV. ("the Terrible") of Russia (1530–1584), the Hundred Chapter Synod (Stoglav, 1551) approved of Rublev's icon Hospitality of Abraham (inaccurately called Icon of the Trinity

It has recently been argued that a Pentecost icon with Mary in the centre forgets the ecclesial position which reserves that place for Christ and is thus not canonical. Since the Mother of God stands for the Church, to place her at the centre of the Apostles would imply reduplicating the image of the Church, especially since the earliest known portrayal of Pentecost, the Rabbula Codex (586), has Mary on the reverse side in the centre of the Ascension icon, while she is completely absent from the icon of Pentecost for the reasons mentioned above.15 Some researchers go so far as to derive an Orthodox ontology from the iconostasis as the transfigured correspondent in Church life to our aspirations in private dreams.16

These interrelations have sometimes given rise to polemics, even between Orthodox Christians themselves. Thus Rublev's Hospitality of Abraham is almost absent in the Greek Orthodox world: For the Greeks, the canonical icon of the Trinity is the baptism of Christ,17 aptly called Theophany in correspondence with the Western concept of "Epiphany" and likewise called Богоявление in Russian.18 Formerly common accusations stating that Western sacred images were "Nestorian" because they reflected only the human side of religion, whereas Orthodox liturgy was criticised in the West as being "crypto-monophysite" because it one-sidedly stressed the divinity of Christ, have lost ground since 1950 owing to ecumenical sensibilities.

Educational Setup and Theological Formation

As the crisis of Iconoclasm shows, icons could extend disputes from the theological level to the popular. Yet formal education and theological formation helped to clarify some of the presuppositions and thus permitted carrying on the discussion at a deeper level. Where formal training was lacking, religious apologetics or polemics could quickly degenerate into fanaticism and intolerance. In contrast, wherever a sound education and formation were imparted, protagonists could be surprised by their intellectual understanding for positions other than their own, in what may sometimes be called ecumenism ante litteram. For a fruitful insemination of ideas, much depended, especially in the second part of the period under consideration, on sharing common ideals. These were largely those of the Enlightenment, ideals espoused by theologians like Eugenios Voulgaris (1716–1806). For this reason, however, Voulgaris encountered harsh criticism after he had been appointed director (1753) of the Theological Academy on Mount Athos

The conflict between the enlightened writer Aleksander N. Radishchev (1749–1802) and Tsarina Catherine II show, however, how superficially rooted these ideas were in Russia. Far from being welcomed as a "Horizontverschmelzung",20 a fusion of horizons which later, in the 20th century, was to allow for a freer intercourse of ideas, progress in theology was viewed with suspicion from the start. It was only after 1922 that the 200 or so intellectuals exiled by Vladimir I. Lenin (1870–1924) re-grouped in several capitals in the diaspora in Western Europe, thus creating infrastructures for a free exchange of ideas, both among themselves and with the now closer West. To a lesser extent, the same effect had been attained during the diaspora of Byzantine intellectuals, following the fall of Constantinople.21

Orthodox education in general suffered as long as vast parts of Central and Eastern Europe and Asia Minor were under Muslim domination. Instruction was restricted to monasteries and to the catechism promulgated in the Church, although, from the 18th century onwards, conspicuous efforts were made to found schools, as on Mount Athos and in Constantinople

Western Europeans' desire to become acquainted with the Orthodox religion met these Orthodox educational and formative projects halfway. In Rome, Pope Gregory XIII. (1502–1585) created the Greek College (1576) and the Maronite College (1584) which were both established for the training of Catholic Eastern rite priests and entrusted to the Jesuits. The Greek College was particularly well suited for the encounter of Easterners and Westerners, that is, of Catholics such as the great scholar Leone Allacci (ca. 1586–1669), whose ecumenism found expression in his The Western and Eastern Churches in Perpetual Agreement, and of Orthodox Christians.22 At this point, however, we might rather call this an encounter between traditions, as all purported to be Catholics, being students in Rome. Thus, Feofan Prokopovič (1681–1736), who had become Catholic for a time, then returned to Orthodoxy to become Peter the Great's (1672–1725) presumed ghost-writer for the "Ecclesiastical Regulation". Besides, he introduced many Lutheran elements into Orthodox theology, such as the affirmative formula of absolution in confession in the first person, and the assumption that there are only two sacraments, namely baptism and the eucharist. However, Orthodox scholars also had contacts with other Western traditions to whose institutions they could send their students: for instance, Patriarch Kyrillos Loukaris sent Metrophanes Kritopoulos (1589–1639) to study at Balliol College, Oxford (1617–1622), partly with George Abbott (1562–1633) who was to become Archbishop of Canterbury (1611–1633). Nevertheless, Kritopoulos signed the anathemas against his benefactor Loukaris after he had become Patriarch of Alexandria (1636–1639).23

The closeness of Orthodoxy to the Anglican Church manifested itself several times. The Nonjurors of 1688, refusing to swear loyalty to King William III. (1650–1702) and Queen Mary II. (1662–1694) out of loyalty to King James II. Stuart (1633–1701), who had been ousted by the Glorious Revolution, in vain attempted to establish some sort of communion with Orthodoxy (1716–1725).24 Nevertheless, the closeness was greater in this instance than in the letters (1575–1581) exchanged between some outstanding Wuerttembergian Lutheran divines, such as Jakob Andreae (1528–1590), Lukas Osiander the Elder (1534–1604), Jakob Heerbrand (1521–1600), and the Greek specialist Martin Crusius (1526–1607) and their Orthodox correspondents, namely John Zygomalas (ca. 1498–ca. 1584), his son Theodosios Zygomalas (1544–ca. 1614), and others writing on behalf of Patriarch Jeremias II. Tranos (ca. 1536–1595).25

Later, at the time of the Oxford Movement (1833–1845) within the Anglican Church, William Palmer (1811–1879) of Magdalen College travelled to Moscow (1841)26 and to St Petersburg (1842) in order to test the Three-Branch Theory propounded by his namesake of Worcester College. According to this view, in schism the Church consisted of the Anglican Church for the English-speaking peoples, of the Roman Church for those with Romance languages, and of the Orthodox Church for Greeks and Russians. Rejected both by Vasilij M. Drozdov (1783–1867), the Moscow Metropolitan who refused him communion, and by the Holy Synod, which refused to acknowledge the Anglican Church on the terms of the Three-Branch Theory, Palmer nonetheless corresponded with the Russian lay theologian Aleksej Khomiakov. This contact essentially influenced Khomiakov's publication The Church is One,27 a starting-point of modern Orthodox theology. Still later, after the First Vatican Council (1870) and difficulties raised over the issue of the pope's infallibility, the two international Bonn Reunion Conferences (1874–1875) were organised by Johann Joseph Ignaz von Döllinger (1799–1890) for an assembly of Old Catholics, Lutherans, and Anglicans, but these again did not establish communion. Eventually, however, Vasilii V. Bolotov (1854–1900), taking up their results, came up with his famous theses on the filioque,28 which have proved to be ecumenically fruitful.29

The Moscow and Kievan Approaches

The clash of pro- and anti-Latin ideas, as well as their positive resonance, may be seen in the tension between the Moscow and the Kievan approaches to theology, a tension which had gradually developed and which involved other networks such as the monastic system and the printing press. This was due to what some (such as Florovsky) called the imbalance created by the surreptitious introduction of Western ideas. Others, like Alexis Kniazeff (1913–1991), rector of Saint-Serge, Paris (1965–1971), considered the reason to be the inevitable and even beneficial exposure to ideas which break the rigidity of the system.

Now that the scriptural books and the liturgical texts were more easily available, there was a call for an improved version. The story is, however, more complicated than it would seem. After St. Maximus the Greek (ca. 1470–1556), himself also caught in the Eastern / Western network of attraction and repulsion, had completed his studies in Florence, where he became a Catholic and for two years was even a Dominican, he betook himself to the Orthodox monasteries of Mount Athos. There he was invited, as a polymath, to go to Russia and correct the liturgical books.30 Yet his involvement with the Hesychast movement of St. Nil Sorskij (1433–1508) in opposition to St. Iosif Volockij (ca. 1440–1515) and his criticism of the Tsar ensured that he would pass the rest of his days in monastic prisons. A hundred years later, the effect of the printing press had boomeranged, so that a second attempt to correct the liturgy books, this time by Patriarch Nikon, was successful with the Church. However, the successors of Iosif Volockij, from whose ranks later many of the so-called Old Believers or Old-Ritualists emerged, disagreed, thus resisting the corrected liturgical books and preferring to keep the old traditions, regarded as "Russian".

Against the background of this network, the whole initiative of publishing more correct books led to a call for a more adequate religious education. Orthodox literature should be capable of competing with the books coming from the West. These thoughts led Petro S. Mohyla (ca. 1596–1645)[

Moreover, Mohyla conceived of a plan to achieve Christian unity which would not end like the Union of Brest (1596), where the Ukrainian prelates led by Ipatij Potij (1541–1613) and Cyril Terelskij, seeking distance from Constantinople and unity with Rome, had been disappointed. In other words, they had desired unity between their Church and Rome, but not according to the unionist model. Besides, in contrast to the Council of Florence (1439) which had spoken of the Church in terms of patriarchates, they were now facing the Council of Trent (1548–1565) with its post-tridentine exclusivist ecclesiology, which seemed to be suspicious of any other Church.31 This situation led to a division of the Ukrainian bishops, with the result that their high hopes were dashed. Mohyla, who was born in 1596, strongly opposed the Union of Brest of that year, which had spelt out such a disaster. Still, his own plan for a union as a double merger with Rome and Constantinople, outlined in his work Sententia cuiusdam nobilis Poloni graecae religionis (Opinion of a Polish Nobleman of the Greek Religion, 1644) was not successful, either.32

As a side effect of Mohyla's activities, we can see the rise of two schools.33 The theological school of Kiev was more open to the West, and it is from this school that St. Demetrius of Rostov (1651–1709) would emerge, who was talking in terms of the Immaculate Conception long before it was proclaimed as a Catholic dogma. The Moscow School, however, initiated by the Greek brothers Ioannikios (died 1717) and Sophronios Leichoudēs (1652–1730), soon became intransigent towards Rome, thus sowing the seeds of discord. When the brothers reached Moscow in 1685, they launched an attack against the writer Sil'vestr Medvedev (1641–1691) and his pro-Latin theology. In return, Patriarch Ioakim (1620–1690) named them heads of the Greek-Latin Academy. Their proposed nostrum was a return to the Greek tradition to counteract Medvedev's errors. Medvedev himself had previously replaced Simeon of Polotsk (1629–1680) at court as a theologian, preacher, and poet. However, Regent Sophia's (1657–1704) attempt to make him head of the Academy was thwarted by Patriarch Joachim's preference of the Leichoudēs brothers.34

It is evident that the clash between the Kievan pro-Latin origins of Mohyla's Theological Academy and the blatantly anti-Latin premises of the Leichoudēs brothers (capitalising on the strong anti-Latin feelings stemming from the Times of Troubles between 1603 and 1612, when Polish troops had seized Moscow, and even before), set Russian theologians on anti-Latin premises which proved persistent and which could only be combated thanks to the awakening of a critical philosophy. On the Red Square in Moscow, a monument

Mount Athos, a Centre of Learning and Freedom

In Orthodoxy, there was one privileged place of encounter, and that was Mount Athos.35 Since it was frequented by many intellectuals of all kinds and from all countries of Orthodoxy as well as the diaspora, it enabled new movements to emerge. The Bulgarian Paisij of Hilandar (1722–1773), the Serbian monastery

A whole set of ideas connected with Hesychasm and the prayer of Jesus came to the fore. Since theology, to Orthodox Christians, is based on the union of dogma and spirituality, this led to a renewal of theology which flourished on Mount Athos around the middle of the 20th century. The works of Panayiotis Nellas (1936–1986) and Basilios Gontikakis are emblematic of this phenomenon.37 This new theology, with its return to the spirit of the Fathers, served as an antidote to then prevalent theology of Panagiōtēs Nikolaou Trempelas (1886–1977). His theology is criticised as being tied more to the letters of the Fathers and the need to repeat them than to their actual spirit and inspiration.38 On Mount Athos, as in other Orthodox centres, the general decline of learning hit hard because of a constant brain-drain and insufficient financial support.

Serbia had begun to develop its own consciousness, not only politically. Its spiritual-religious identity had its roots in Mount Athos, thanks to the monastery of Hilandar and its founder, the prince St. Sava (ca. 1174–ca. 1235), first archbishop of the Serbian autocephalous Church.39 Under Ottoman rule, things had changed. After the famous trek of thousands of Serbs headed by Patriarch Arsenije III. (1633–1706) in a bid for independence from the Austrian Empire of Leopold I. (1640–1705)[

Since exiled individuals were welcome in the adopted country, it became the basis for an intellectual network, with Fruška Gora

The situation in Serbia served as a catalyst for the publication of liturgical and theological books. It was partly the Belgrade Metropolitan Mihailo Jovanović's (1826–1898) good relations with the Russian Church that made this possible. In fact, Jovanović himself wrote the first history of the Serbian Church in 1856. Meanwhile, theological support came from Montenegro. This region had asserted its independence from the Turks all along and now gave rise to a rudimentary Christology, written by Petar Petrović Njegoš II. (1813–1851), who was a prince, poet, and bishop. The most illustrious name, however, is that of the bishop of Zara, Nikodim Milaš (1845–1915), a canonist who inspired other famous canonists. One of those was a Russian theologian teaching in Belgrade, Sergije Troitski, who edited St Sava's Kormčaja Kniga ("Book of the Helmsman", 1219) which had become the core of the Russian and Bulgarian Churches' canonical legislation.42 In fact, Russian theologians in exile also founded the Faculty of Theology in Belgrade, the first one in Serbia, in the period after World War I.

Even more dramatic was Orthodox Romania's intellectual development. After Diaconul Coresi (died ca. 1583) had laid the foundations of the Romanian language by translating liturgical and biblical books from Slavonic into Romanian, a series of other theological writings made these foundations more solid. The works of the Ukrainan Paisij Veličkovskij, who worked in Romania, are the best known in this context. At Mount Athos, a coenobitic skete (a hermitage or a smaller monastery attached to a bigger one) with Romanian services was created by Paptapie and Grigorie, two Moldavian monks. However, it was closed in 1821 because of the Greek War of Independence. Thirty years later, Nifon and Nectarie, two other Moldavian monks, started another skete where services were held in Romanian after Moldavia and Wallachia were united in 1859.

As a result of this self-affirmation on a national and an ecclesial level, a number of new issues had to be discussed in the newly approved Churches: the proliferation of seminaries and the careful delimitation of their way of life and works, the need for professors, books, and other publications.43 The Catechism of St Filaret Drozdov of Moscow was now translated, serving as a model for other catechisms and compendia, and theological compendia were launched, such as Preotul ("The Priest"). The Romanian Orthodox Church enjoyed a certain freedom of publication even under Soviet rule, so that the Romanian Philocalia of Fr. Dumitru Stăniloae (1903–1993) was able to be published, of which four volumes had already appeared by 1948.44

Modern Schools

After Greece became independent in 1831, the country sought to set up a theological faculty in Athens. Owing to the influence of Germany – the first king of independent Greece was the Bavarian Otto I. (1815–1867), a Catholic – the Lutheran model was adopted both for the Synod and for the theological faculty, which for the first time was independent of the Church. In spite of limitations, this faculty became a forcing house for Greek theology, and the academic results were by no means negligible. Unfortunately, the early years were overshadowed by a conflict between two theologians, the progressive Theoklētos Pharmakidēs (1784–1860), professor at the same faculty, and the conservative Kōnstantinos Oikonomos (1780–1857), a theologian and reformer. Oikonomos went so far as to oppose the first translation of the Bible into Modern Greek, which had been carried out by Neophytos Vamvas (1770–1855). Remarkably, translating the Bible into Modern Greek was prohibited by law until 1973.

The Theological Faculty of Thessaloniki, on the other hand, was only created after much of Greece's northern territory had been freed from Ottoman rule in 1912. The university was founded in 1925, but the faculty of theology was opened as late as 1942. Soon a competition between the two leading universities set in, with Athens showing a more conservative streak and Thessaloniki being more open to new ideas.45

After the Mohyla Academy was closed by Tsar Alexander I. (1777–1825) in 1817, Nikolaj Protasov (1798–1855), who became Chief Procurator (ober-prokuror) of the Holy Synod in 1836, reorganised theological teaching in four Academies: St Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, and Kazan.46 These academies divided between them the teaching of all the patristic writings and gave rise to a flowering of patristic and liturgical learning which characterised pre-revolutionary Russia. When these schools closed, their task was taken over by the schools of the diaspora, which quickly attained international fame.

The first to establish itself was the Saint Serge Orthodox Theological Institute

Propagation of Ideas Through Synods

Owing to the synodic or collegial structure of the Orthodox Church, synods are the most natural locus theologicus for the creation, clarification, and propagation of theological ideas, second only to the other place of encounter of divine summoning, the liturgy.49 Again, a few words about the synodic character of theological ideas seem appropriate before a few synods of the period are mentioned which characterise the growth and development of Orthodox networks. Assemblies of the faithful may be either liturgical or para-liturgical. The former are normative, to the extent that the acceptance of ideas depends on whether an idea is to enjoy the stamp of Church approval. A feast or a synod, for example, may be celebrated or not, and not just in one local church (the Orthodox use this term, rather than the Catholic particular church), but in all the churches. An unused idea, however, is not simply devoid of the stamp of officialdom, for a theological idea or movement dies if it is not aired.

As in patristic times, grass-roots support by monks or even by the market pedlars – if St. Gregory Nazianzus (ca. 329–ca. 390) is to be credited – could help to defeat a dangerous trend or secure its opponents' victory. The Council of Florence (1439) never gained popular support because there was opposition at the base. Thus, its tardy proclamation on the eve of the fall of Constantinople did not achieve anything except that it was rescinded by the four patriarchs of the Synod of Constantinople in 1482.50 When the Ukrainians' union with Rome at Brest (1596) seemed as good as certain, the opposition of the confraternities in the Ukraine instigated by Prince Kostjantyn Ostroz'kyj (1526–1608) torpedoed it and changed the minds of a good number of its bishops and of the Orthodox faithful. In Orthodoxy, laypeople play a more active part than in Catholicism, as theologians and participants in synods. The fact that at the Synod of Moscow (1917–1918), which re-established the Moscow Patriarchate, all of its members, whether bishops or laypersons, gave a single vote was criticised by Florovsky, who considered it to be a violation of tradition. This judgment, however, did not condemn the Moscow Synod to a damnatio memoriae. The reforms it endorsed might have launched the Church into the future, were it not for the Soviet interlude.

After the Council of Florence had disappointed the Orthodox in mid-15th century, the synods concerned with the problems created by the Reformation and Counter-Reformation took over most of the agenda. Part of the problem arose because the Orthodox, not having competent Orthodox schools, often resorted to arguing on the side of Catholics against Protestants or on the side of Protestants against Catholics. This created confusion as to the intentions of Orthodox scholars and their means, especially when one of the most gifted patriarchs of Constantinople, Kyrillos Loukaris, published his creed influenced by Calvinism in 1633.51

The first major synod that dealt with the issue was the Synod of Jassy (1642), which had been assembled to judge what had been produced by Mohyla. Though attendance was meagre, the outcome was stunning: The resulting document Expositio fidei ("Exposition of the Faith", 1640) seemed very close to Catholicism, especially before it was expurgated by the Greek theologian Meletios Syrigos (1585–ca. 1662). Since this document proved to be an insufficient answer to the Reformation, the Synod of Jerusalem was convoked (1672) by Dositheos (1641–1707), who had become Patriarch of Jerusalem at the age of 27.52 Though he was constantly on the road to collect money, he established a council for Jerusalem in 1669. Despite his criticism of the Roman Catholic Church, he used Catholic terms such as "purgatory" (which he later gave up) and "transubstantiation" in his Confession of Dositheos.

The Retrieval of Orthodoxy

Once modernity set in and Orthodox theologians were in a position to question the accepted wisdoms of the past, two schools of theology were established in order to retrieve an "orthodox" Orthodoxy which would be free from inauthentic elements, in the new forms of modern thought. One of them was Florovsky's neo-patristic school, which was later also propagated in the United States, and the other was Sergei N. Bulgakov's Russian School in Paris.53 Both were bitter fruits of the October Revolution, for both were propagated by theologians in exile. The fact that they represented contradictory but persistent tendencies proved that they touched deep chords in Orthodox hearts.

According to Florovsky, a Russian from Odessa, the Graeco-Byzantine world was a sine qua non condition for the Christian message to come home. His work aimed at basing theology on patristics, a study of the Church Fathers read from the perspective of the Byzantine reconstruction of Eastern theology. With the help of the Fathers' original words, he was confident that he could free theology from the encrustations of various types of pseudomorphosis and enable it to nourish itself on an authentic liturgy. However, Florovsky's own example, though it made some disciples, was largely negative, since it delineated a deconstructive programme, especially if one takes Ways of Russian Theology as an example.54

Sergei N. Bulgakov, coming from the world of economics and philosophy, thought that the best thing that could be done was to reach out to the secular world on its own terms and initiate a dialogue with modern philosophy. To him, however, modern philosophy was largely a matter of taking as one's point of departure Vladimir S. Soloviev's (1853–1900) many-splendoured system of philosophy in which sophiology plays a key part.55 It was precisely here that the two systems clashed. Bulgakov insisted that God's own nature was wisdom, whereas Florovsky argued with the Greek Fathers that wisdom was the incarnate logos.56 Eventually, the two schools made generations of young theologians aware of the fact that theology cannot content itself with repeating dogmas in a parrot-like way. Many, like Panagiōtēs N. Trempelas, attempted precisely this imitation, but one needs to follow the Fathers in a more existential way, as an experiment which reflects human behaviour in the light of divine wisdom and touched by grace.

Once some traditions were being discussed, others followed. People started adopting a fresh approach to icons, liberated from the mists of the centuries, especially thanks to Pavel Florensky's work Iconostasis and Léonide A. Ouspensky (1902–1987). Palamism, which had until 1940 been considered dead and gone, for instance by the Catholic scholar Martin Jugie (1878–1954), suddenly came back to life. It dominated much of subsequent Orthodox theology, thanks to Fr. Dumitru Stăniloae's initial retrieval in philocalic élan. Besides, Vladimir Losskii gave it a contemporary theoretical framework known as neo-palamism, and John Meyendorff popularised it. The form of prayer it incorporated, Hesychasm, soon experienced an unprecedented vogue.

Ecumenical Breakthrough

Orthodoxy, although it has often been criticised as a regressive religion, was a pioneer in ecumenism, long before the Catholic Church moved in and especially after 1900. The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Ioakeim III. (1834–1912) published an encyclical letter with the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 1920 which marked an epoch. Only a few decades earlier – in 1848 – the Patriarchs of the East in union with Constantinople had answered Pius IX's (1792–1878) appeal to reunite with the Catholic Church with a blunt "no".57 Although not all Orthodox Churches followed suit at once, and some of them later withdrew on various pretexts, the Orthodox Church clearly took the lead in the foundation of the World Council of Churches, the Faith and Order Commission (both in 1948), and other important ecumenical groups. Among those who have made a name for themselves are Patriarch Athēnagoras I. (1886–1972),58 and, even earlier, the Bulgarian theologian Stefan Tsankov (1881–1965),59 who participated actively in ecumenism right from the start. His Orthodoxes Christentum des Orients ("Orthodox Christianity of the Orient", 1928), a series of lectures held in German, shows his closeness especially to the Protestants with whom he had worked and studied. Sergei N. Bulgakov had already propagated intercommunion with the Anglicans in the context of the Confraternity of SS. Alban and Sergius, but the time was not yet ripe for his proposals.60

One must remember that there had been many contacts between Orthodox and the various other denominations, sometimes within an atmosphere of reservation, as was possible for Catholics before the Second Vatican Council. For one thing, Vasilij V. Bolotov's three grades of truth61 introduced a sort of hierarchy of truths into the hieratic concept of theology which had until then been prevalent in theology. Besides, having to compete with the claims of other denominations in dialogue made many Orthodox Christians rethink the theological foundations of their religion, as we can see in the first inklings of Eucharistic ecclesiology with Fr. Nicolas Afanassieff (1893–1966), before 1950.62

Although Orthodoxy is mostly considered to be a contemplative rather than an active religion, the Orthodox religion gained new territories in the period between 1450 and 1950, in countries including Alaska, China, Japan, and Finland.63 But besides evangelisation, Orthodox Christians have been taking an active part in bringing God's message to people seeking it, for example in the work of the organisation and publishing house Apostolike Diakonia, which was established in 1936 and has its headquarters in Athens. This institution, an answer to the Zoe Brotherhood, a Western-type association of lay theologians, distributes theological and catechetical works in various countries. Through such institutions and those of higher education, Orthodoxy is able to make its voice heard in the traditional Orthodox countries as well as in the diaspora. At the same time, in the five hundred years under consideration, the world has changed almost out of recognition, especially if we think of the technical prowess that has become the hallmark of contemporary times, and so has (to a lesser extent) the world of Orthodoxy.

Further Perspectives

Yet, in 1950, few could have imagined the surprises that lay in store. After the devastations of the Second World War, the "Iron Curtain" fell on the part of Europe which included the traditional countries of Orthodoxy. Eastern Europe now seemed more sealed off than ever before. Still, after a few years, the dialogue, which the Orthodox Church had been among the first to encourage, was to bring abundant fruit, thanks to the changed atmosphere created by the Second Vatican Council. This positive turn of affairs had already been heralded by the foundation of the Ecumenical Institute at Bogis-Bossey, Switzerland, in 1946. Orthodox Christians were to play a significant part in this institution. At the same time, a more genuinely Orthodox theology developed in both the traditional and the diaspora centres of learning which was capable of engaging in a dialogue with the contemporary world.64