Introduction

In the early modern composite state, recent scholarship on the subject of empires has called attention to a specific form of political rule that offers great potential for comparative research.1 Historians of the early modern era have already done much to identify the defining traits of these dominions.2 As dynastic agglomerations, composite states were formed of at least two territories which, while united under a single monarch, nonetheless tended to retain a high degree of political, judicial, economic and cultural heterogeneity. In this respect, they differed fundamentally from the modern nation states, classically defined by the triad of people, territory and power.

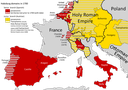

In some cases, the realms forming these territorial conglomerates were geographically dispersed. The most familiar example is probably the Spanish Empire, which had possessions across the European continent as well as its overseas colonies. Early modern Brandenburg-Prussia, with its territories dispersed from the lower Rhine to the Duchy of Prussia, is also a case in point.3 On the other hand, there were composite states whose component parts existed within a single set of borders, with examples including the Swedish Empire, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the United Kingdom or Piedmont-Savoy.

Drawing on two concrete examples, the following discussion aims to bring together the study of early modern composite states on the one hand and empires on the other, thereby demonstrating the potential of trans-regional and trans-national approaches.4 However, we would be well advised not to make anachronistic comparisons between modern empires and early modern structures of dominion.5 The aspects specific to pre-modern rule must always be borne in mind if misleading analogies are to be avoided. Nor should we forsake conceptual precision: not every composite state was an empire. Considering the two concepts side by side is further complicated by the imprecision attending that of "empire", for it has been observed that "empires have come in many shapes and forms, at many places and in many times".6 In an effort to render empires describable, the field of empire studies uses the demarcation against other forms of rule on the one hand and increasingly performative approaches on the other in order to examine techniques of rule and administration and the actors involved in them.7 Yet there is still no consensus how exactly empires ought to be defined.8

By contrast, recent scholarship has identified a range of phenomena that characterised composite states. Traditionally, special attention has been devoted to their inner structure and the tension between centre and periphery. Was there a true centre of power, and is it possible to prove deliberate efforts to orient the individual territorial components towards it in political, economic, confessional, cultural, linguistic or other terms? Or should we not instead assume a practice of political rule whose structure was largely polycentric? The answer to such questions is of considerable importance, not least with respect to the debate on "absolutism" as a form of rule – a debate which has attracted significant new contributions in recent years.9 In contrast to the older historiography, newer research has found that early modern monarchs were fundamentally dependent on the cooperation and consensus of local and regional elites. Any attempts on the part of the ruler to enforce a policy strictly oriented towards his centre of power was likely to meet with resistance – particularly at the periphery. Against this background, there is much to be learnt from an actor-centred perspective that examines the personal ties that existed between centre and periphery or that were purposely created in the course of a policy of clientelism and patronage – created, that is, with a view to generating loyalty, furthering integration and enforcing the ruler's writ even in remote areas of his realm.

A closely related trans-epochal phenomenon is that of rule being delegated.10 The ruler's claim to exercise governmental authority in each territory of his disparate realm posed a problem for many composite states. For in practice, rule from afar turned out to be far more difficult than when the ruler was permanently present in a given place. One means by which this deficit might be supplied was for the ruler to tour his dominions. This instrument posed severe logistical challenges. Another widespread practice was to instal a deputy (under a title such as steward, viceroy or governor-general) to maintain a permanent presence as the monarch's alter ego, thereby ensuring the exercise and supervision of his rule even in his absence. Since, in the early modern era, authority and rule were widely understood in a personalised sense, establishing such deputies as mediators between the centre of power and local elites was a widely used means of compensating for the lack of a permanent presence of the monarch himself.

or governor-general) to maintain a permanent presence as the monarch's alter ego, thereby ensuring the exercise and supervision of his rule even in his absence. Since, in the early modern era, authority and rule were widely understood in a personalised sense, establishing such deputies as mediators between the centre of power and local elites was a widely used means of compensating for the lack of a permanent presence of the monarch himself.

Another characteristic feature of larger composite states is an unmistakable tendency to pursue claims to universal rule and to justify them by means of an imperial ideology.11 The most notable example is the guiding concept of monarchia universalis, which attained considerable political importance in the age of Emperor Charles V (1500–1558) in particular and which was instrumentalised to justify or refute claims to universal rule.12 The extraordinary duration of the Thirty Years' War, for instance, has been explained in terms of the incompatible claims to universal rule on the part of the main competing powers, Habsburg, France and Sweden.13

A related question which was discussed even at the time concerns whether and to what degree composite states, by reason of their spatial conditions, were at greater risk of finding themselves at conflict with neighbouring powers.14 Since they often entailed the creation of powerful military apparatuses to secure them, did not the large spatial expanse of extended and dispersed complexes of rule promote warfare – all the more so because neighbours tended to view such military build-up as a threat? A well-known example of this dynamic is France's geographical situation between the House of Austria's possessions in the Iberian Peninsula to the south, its holdings in the Low Countries to the north, and the Holy Roman Empire, under a Habsburg emperor, to the east. Resentment of this so-called "Habsburg embrace" in 1700 has long been adduced to explain French policy in the early modern era.15 Much can also be learnt from the tightly interwoven contemporary discourses concerning he political and military demands posed by such dispersed holdings: was territorial integration by means of expansion the goal, or ought the foremost concern to be the preservation of the status quo?16

in 1700 has long been adduced to explain French policy in the early modern era.15 Much can also be learnt from the tightly interwoven contemporary discourses concerning he political and military demands posed by such dispersed holdings: was territorial integration by means of expansion the goal, or ought the foremost concern to be the preservation of the status quo?16

In this context the question of large empires and their supposed pacifying effects has to be considered. Of particular importance here is the traditional guiding principle of a universal peace (pax universalis or pax generalis) and the notions associated with it: hegemony or balance, universalism or particularism, hierarchy or equal status.17 These ideals of monarchia universalis and pax generalis were and remain of essential importance in attempts at legitimising large empires.18 The accurate dictum whereby "empires were made and unmade by words as well as deeds"19 can also be applied to the "composite" monarchies of the early modern age. Justifying and legitimising their own actions was everyday business in composite states and was an established part of their self-presentation and their communicative strategies as pursued through printed propaganda.20

Moreover, to reach an adequate understanding of the emergence, maintenance and decline of composite states and empires, it is important to analyse the integrative power of royal symbols , symbolic acts and performative elements.21 Particularly those techniques of rule aiming at centralisation, standardisation and integration made deliberate use of visible signs and communicative acts in order to create trans-territorial connections.

, symbolic acts and performative elements.21 Particularly those techniques of rule aiming at centralisation, standardisation and integration made deliberate use of visible signs and communicative acts in order to create trans-territorial connections.

The Holy Roman Empire is not infrequently mentioned in discussions of early modern composite states.22 Yet the concept scarcely does justice to the empire's unique constitutional structure, which was defined by the "basic constellation of the coexistence of and correlation between the majestas personalis of the emperor and the majestas realis of the empire".23 These two poles existed in a state of mutual dependence and restriction. The emperor's power was restricted by the "partial legal autonomy" of the territorial lords no less than by the commitment to consensual cooperation on which the imperial constitution was founded. Both enjoyed supra-national validity, a fact which increased the scope for action on the part of the imperial estates while also imposing limits on what they could do.24

no less than by the commitment to consensual cooperation on which the imperial constitution was founded. Both enjoyed supra-national validity, a fact which increased the scope for action on the part of the imperial estates while also imposing limits on what they could do.24

This study will take a closer look at two composite states which hitherto have not been adequately compared: the early modern empires of Sweden and Spain.25 To compare them seems both legitimate and worthwhile, since both were among the great powers of the 17th century whose competing claims to dominance contributed to the exceptionally high density of conflict witnessed by that era.26 Unlike Spain, however, empire scholars have so far largely ignored Sweden. Moreover, both powers are widely held to have seen their position among 18th-century states decline.27 Both were unable to maintain their great power status, and both composite states thus offer striking illustrations of the triadic narrative of the rise, decline and fall of empires.28 Another similarity can be found in the fact that in the early modern age, both Sweden and Spain harked back to their Gothic heritage as a means of articulating and legitimating their far-reaching claims to dominance.29

The Swedish Composite State in the Early Modern Era

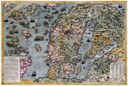

The development of the Swedish composite state began in 1561 , when the city of Reval (modern Tallinn) placed itself under the protection of the Swedish Crown.

, when the city of Reval (modern Tallinn) placed itself under the protection of the Swedish Crown. Sweden's territorial growth peaked in 1681, when its king inherited the County Palatine of Zweibrücken. This marked both the high and the end point of Swedish expansion.30 Swedish historians refer to the period between 1611 and 1718/21 as the stormaktstiden or "Age of Greatness", thereby creating a conceptual link with empire studies. This was also the period when Sweden tried to establish colonies in Lapland as well as overseas, in Africa and North America.31 Sweden's "imperial experience" ended with the death of Charles XII (1682–1718).32 The Great Northern War (1700–1721)

Sweden's territorial growth peaked in 1681, when its king inherited the County Palatine of Zweibrücken. This marked both the high and the end point of Swedish expansion.30 Swedish historians refer to the period between 1611 and 1718/21 as the stormaktstiden or "Age of Greatness", thereby creating a conceptual link with empire studies. This was also the period when Sweden tried to establish colonies in Lapland as well as overseas, in Africa and North America.31 Sweden's "imperial experience" ended with the death of Charles XII (1682–1718).32 The Great Northern War (1700–1721) is considered the decisive watershed, at the end of which Sweden lost much of the territory it had gained since 1561. Sweden's 120-year ascent was thus followed by a rapid fall.33

is considered the decisive watershed, at the end of which Sweden lost much of the territory it had gained since 1561. Sweden's 120-year ascent was thus followed by a rapid fall.33

The causes of Sweden's rise are manifold, with historians often describing it as an "empire of necessity".34 By the reign of Charles IX (1550–1611), Swedish expansion was following a political programme that can be seen reflected in the constitutional debates of the time. For instance, in his proposal for a basic law (regeringsform) defining the rights and responsibilities of the ruler, his subjects and the political institutions, Charles IX took care to stipulate that the king of Sweden should travel to receive homage in Livonia. This was at a time when Livonia was not yet part of the Swedish composite state and Swedish rule in Estonia not yet firmly established. This draft law is read as an expression of Sweden's claim to dominance in the Baltic,35 a claim for which Charles IX had recourse to "Gothicism".

Gothicism "created, in a positive reimagining of a negative image of Goths and the Gothic, a self-understanding as a people descended from heroes and warriors".36 This current of ideas emerged in different parts of Europe in the early 16th century. It found particular resonance in Sweden, where it coincided with the country's secession from the Kalmar Union , the personal union of the three Nordic kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden which lasted from 1397 to 1521. Gothicism offered the young Vasa dynasty a tradition within which to situate itself, thereby conferring legitimacy upon its rule.37

, the personal union of the three Nordic kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden which lasted from 1397 to 1521. Gothicism offered the young Vasa dynasty a tradition within which to situate itself, thereby conferring legitimacy upon its rule.37

Under Charles IX and his son Gustavus Adolphus (1594–1632), Gothicism displayed its full propagandistic effect as a political programme. For instance, Charles IX, before departing for the Baltic, had his address to the estates at the riksdag (diet) of 1603 drafted by Johan Skytte (1577–1645), who went on to become chancellor of the University of Uppsala and one of the foremost exponents of Gothicism in Sweden. Skytte's work, together with that of other Gothicist historiographers such as Johannes Messenius (1579–1636), contributed to "positioning Sweden as the dominant power in the Baltic".38

Gustavus Adolphus continued both this policy and the communication strategy accompanying it. As part of the festivities accompanying his coronation in 1617, he delivered a speech at the tournament that was steeped in the spirit of Gothicism. In the guise of Berik, the mythic king of the Goths, and with reference to Berik's conquests in Estonia, Courland, Prussia and the Wendish lands, Gustavus Adolphus formulated the precedent to be followed in his own reign while underscoring Swedish claims in the Baltic.39

Yet this should not be mistaken for the proclamation of an aggressive and expansionist programme. In fact, Gustavus Adolphus justified his foreign policy in defensive terms – including the struggles with Poland in the Baltic and his intervention in the Thirty Years' War. This too was consistent with his cultivation of a Gothicist image, again with reference to the legendary Berik.

Accordingly, the king's ambition "att lägga kust till kust" (to add coast to coast), thereby making the Baltic Sweden's inland sea, should not be taken as a programme set in stone.40 Only gradually does a conscious plan emerge from the actions of Gustavus Adolphus. The key was to seize any opportunity – occasion is the word found in the sources – for making territorial gains and thereby ensuring the outward security of Swedish rule in the Baltic.41 The (territorial) demands made by Sweden during the Westphalian peace negotiations (1643–1649) with a view to obtaining "guarantees" and "satisfaction" form a direct continuation of this programme by the means of realpolitik. As a result, Sweden acquired Western Pomerania as well as the duchies of Bremen and Verden, giving the Swedish crown control of the estuaries of the Oder, Elbe and Weser as well as the southern Baltic seaboard. This put Sweden in a position to control trade in the Baltic and access to the North Sea trade.42

Towards the end of the Thirty Years' War, Sweden reached the limits of its (economic) power. To consolidate state finances, the riksdag of 1655 ordered a reduktion, meaning the reacquisition of former crown lands granted to the nobility. Although this measure was not fully implemented, another – the "Great Reduction" – was enacted in 1680 at the behest of Charles XI (1655–1697). These measures, which continued to be tightened until 1686, were implemented throughout the Swedish composite state.43 Yet even these drastic steps were not enough substantially to relieve the economic strain on Sweden. The Great Northern War brought further financial pressure, causing the military to be overstretched and ultimately ushering in the end of Sweden's great power status.

In Baltic German historiography, which was dominant in Estonia and Livonia well into the 20th century, the "Great Reduction" is the decisive event in assessing Swedish rule. The Swedish era or Schwedenzeit is seen as a period of decline and contrasted as such with the region's subsequent flowering under Russian rule.44 By contrast, the historiography of Sweden's German provinces, on the other hand, to this day gives overwhelmingly positive appraisals of Swedish rule . The popular adage Unter den drei Kronen, lässt es sich gut wohnen ("Life is good under the three crowns") is only one aspect of a diverse culture of popular memory. This divergence in memories of the Schwedenzeit is striking indeed and serve as a stimulus for enquiring into how (early modern) empires are remembered in popular memory. What these divergent memories also testify to, however, is the differing incorporation of the formerly Swedish provinces and their elites into the Swedish composite state and hence different relationships between centre and periphery.

. The popular adage Unter den drei Kronen, lässt es sich gut wohnen ("Life is good under the three crowns") is only one aspect of a diverse culture of popular memory. This divergence in memories of the Schwedenzeit is striking indeed and serve as a stimulus for enquiring into how (early modern) empires are remembered in popular memory. What these divergent memories also testify to, however, is the differing incorporation of the formerly Swedish provinces and their elites into the Swedish composite state and hence different relationships between centre and periphery.

On account of the distance from the ruling centre in Stockholm and their potentially perilous marginal position, the Baltic and German provinces of the Swedish crown were treated as "special administrative units".45 They were considered governorates-general, each headed by a governor-general, and constituted "the outermost zone of Swedish territorial administration".46 Between the centre (Stockholm) and the periphery, the län situated in Sweden and Finland formed something of an inner circle.47 This administrative structure reflects the expansionist programme of Gustavus Adolphus and his chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna (1583–1654), which aimed to secure Swedish rule by territorial gains.

The distance between the centre of power and parts forming the Swedish composite state can also be discerned in access to political decision-making processes. The regeringsform or constitution drafted by Oxenstierna in 1634 limited representation to members of the estates born in Sweden and Finland.48 This meant that members of the estates in the Baltic and in the subsequently acquired German provinces were excluded from the political process. However, the German territories, though under Swedish rule, remained part of the Holy Roman Empire49 and as such had opportunities for political involvement outside the framework of the Swedish composite state. The Swedish crown, moreover, sent representatives to the Imperial diet, thereby adding to the ties between these two early modern polities. The Holy Roman Empire's policies and constitution became matters of concern for the Swedish crown, which in turn tried to discuss matters of (foreign) policy within the framework of the Holy Roman Empire's constitution and its institutions.50

No less restrictive were constitutional regulations governing appointments to the Swedish riksråd or Council of the Realm, whose members must likewise be born in Sweden or Finland.51 This was a deliberate attempt to protect the noble families hitherto dominant in the riksråd and thus in key positions of political influence from the promotion of new elites. In particular, it was a backlash against attempts made by Charles IX in the early 17th century to give the Estonian nobility access to the riksråd as a means of broadening his legitimacy in that country.52

This makes it all the more surprising to find that, where the judiciary was concerned, the distance between the Baltic provinces and the ruling centre was virtually eliminated by their incorporation into the legal system on an equal footing. The third of four supreme courts was installed in Dorpat in 1630 – after the Svea hovrätt (Swedish Court of Appeal) in Stockholm (1614) and the court of appeal (hovrätt) for Finland in Åbo (1623), and before the Göta hovrätt in Jönköping (1634).53 A similar observation might be made with respect to ecclesiastical administration. Particularly (but, as the following section will show, by no means exclusively) in the sphere of Church policy, a comparison with Spain suggests itself – not least because early modern Sweden has been referred to as "the Protestant Spain".54

The Rise and Fall of the Spanish Composite State

The Spanish composite state is undoubtedly the instance par excellence of this specific form of early modern polity and as such has been particularly well researched.55 King Philip IV (1605–1665), on whose reign this section will focus, ruled over an impressive array of territories. Yet even contemporaries struggled to find an adequate term for this extraordinary accumulation of dominions, and modern scholarship continues to use a variety of terms, including España(s), nación española, monarquía hispánica, corona católica etc.56

Contemporary observers also participated in lively debates on the structural problems resulting from the extraordinary expanse of this "composite" monarchy.57 In his Idea de un príncipe político Cristiano (1640), a book of instruction for the Christian prince (or "mirror for princes"), the Spanish writer and diplomat Diego de Saavedra Fajardo (1584–1648) dealt at length with the rise and fall of great empires.58 In his book Idea de un príncipe político cristiano , which was soon translated into several languages, Saveeda concluded that the fate of empires obeyed the cyclical law of nature, being doomed either to rise or to fall ("O subir o bajar").59

, which was soon translated into several languages, Saveeda concluded that the fate of empires obeyed the cyclical law of nature, being doomed either to rise or to fall ("O subir o bajar").59

There was a widespread awareness within the Spanish monarchy in the mid-17th century that the hegemony that had been fought for and won in the 16th century was eroding and that the empire had gone into decline.60 Indeed, the word declinación was frequently used to express this sense of crisis. Of particular interest within the present context is that fact that contemporary commentators in Spain thought they had identified a direct connection between the large number and extent of territories making up the Spanish composite state on the one hand and the increasing number of wars in which Spain was involved (and which gave rise to a sense of crisis) on the other.61 From this observation, Saavedra deduced the necessity of following a largely defensive foreign policy and rejected overly ambitious expansionism.62

Cautionary voices began to be raised even in the late 16th century, warning that size presented a liability for extensive monarchies.63 Additional difficulties were to be expected if the countries situated between the empire's component parts were hostile or competing states.64 Such problems were also discussed outside Spain. Cardinal Richelieu (1585–1642), for instance, chief minister of France, considered the distances separating Spain's possessions to be among the few reasons why Spain had not yet fulfilled its ambition of creating a universal monarchy.65 The French king, by contrast, ruled over a self-contained realm, which was far easier to secure, as the Spanish scholar Baltasar Alamos de Barrientos (1555–1640) observed in 1598.66 His compatriot, the Jesuit writer and philosopher Baltasar Gracián (1601–1658), came to a similar conclusion. In El Politico (1640), Gracián argued that France had natural borders – coasts, rivers and mountains – that made it easier to defend than the Spanish empire.67 The monarchies of France and Spain were frequently contrasted in this way within a closely connected European discourse.

A decisive cause of the manifest erosion of the Spanish empire were conflicts between the Castilian centre and the periphery. These conflicts were observed throughout Europe and were much discussed by contemporary writers. Much quoted in this context is a secret memorandum, dated 25 December 1624, by Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel, Rivera y Velasco de Tovar, Count-Duke of Olivares (1587–1645).68 Olivares, for many years an influential favourite at the Spanish court, clearly recognised that the survival of the Spanish empire depended crucially on sparing Castile, which had to bear the brunt of the ongoing wars, any further financial and military burdens. It was time, Olivares argued, for the other territories of the Spanish crown to contribute their fair share. The best-known measure to that effect was the ultimately doomed unión de armas (union of arms), which was to raise money for wars by ensuring the equal taxation of the crown's non-Castilian lands.69 It was virtually inevitable that Olivares' plan would meet fierce resistance. In the 1640s Catalonia, Portugal, Naples and Sicily were shaken by revolts that were to have serious long-term consequences.70 What was more, in the Peace of Münster (30 January 1648) , the king of Spain was forced to recognise the independence of the Dutch Republic, which had seceded from the Spanish Netherlands. Against the backdrop of this challenge to the integrity of the Spanish monarchy, it may understood why Gaspar de Bracamonte y Guzmán, Count of Peñaranda (1595–1676), who led the Spanish delegation, should have called the Congress of Westphalia a council of heretics, a nest of serpents and a tragedy.71

, the king of Spain was forced to recognise the independence of the Dutch Republic, which had seceded from the Spanish Netherlands. Against the backdrop of this challenge to the integrity of the Spanish monarchy, it may understood why Gaspar de Bracamonte y Guzmán, Count of Peñaranda (1595–1676), who led the Spanish delegation, should have called the Congress of Westphalia a council of heretics, a nest of serpents and a tragedy.71

The extent to which the European discourse on the nature of the Spanish monarchy was interwoven with general reflections on the rise and fall of great empires is reflected in the aforementioned example of Gothicism. Both Spain and Sweden drew on Gothic ideas, and both not only instrumentalised their shared Gothic heritage for purposes of propaganda and to justify a particular ideology of rule, but made a point of stressing it in diplomatic practice to win support for shared political goals. French deputies at the Congress of Westphalia even observed that a natural friendship existed between Swedes and Spaniards.72 Moreover, in Saavedra, the Spanish delegation had among its members a specialist in Gothic history. The Congress coincided with the publication of his Corona Gótica, Castellana y Austríaca , which strongly emphasised the Gothic heritage shared by Spain and Sweden – a point Saavedra also raised in negotiations with the Swedish delegation.73 To find diplomatic negotiations entangled in such a manner with processes of cultural transfer suggests fruitful avenues for further research.

, which strongly emphasised the Gothic heritage shared by Spain and Sweden – a point Saavedra also raised in negotiations with the Swedish delegation.73 To find diplomatic negotiations entangled in such a manner with processes of cultural transfer suggests fruitful avenues for further research.

Conclusion

Over the course of the early modern era, the Swedish and Spanish composite states experienced developments that seem illustrative of the classical scheme of the rise, decline and fall of empires. The rise to regional, European and (in the case of Spain) global dominance is followed by periods of stagnation and decline, leading by the 18th century to a marked loss of political importance. A great deal of scholarship continues to follow this master narrative when it comes to identifying long-term structures and processes in the early modern histories of Sweden and Spain.

In this context, the present examination of Sweden and Spain has sought to highlight several aspects. Comparative approaches to the study of composite states and empires are important in light of the necessity of challenging the teleological assumptions (homogenisation, centralisation, integration etc.) underpinning much of the older historiography – and all the more so because a transnational approach serves to sharpen our view of typical and distinctive features. It also testifies to the appeal of drawing on case studies that would seem superficially to have little in common and are drawn from different cultural and linguistic spheres. The case of Swedish-Spanish Gothicism, for instance, casts light on previously little-known reciprocal processes of interaction, transfer and reception not restricted to a particular nation state, region or religious confession. Comparative studies of this kind a particularly suitable for bringing both the commonalities and differences between early modern composite states and empires into sharper focus than has hitherto been the case.

Dorothée Goetze / Michael Rohrschneider

Appendix

Sources

Álamos de Barrientos, Baltasar: Discurso político al rey Felipe III al comienzo de su reinado: Introducción y notas de Modesto Santos, Barcelona 1990 (Textos y documentos 7).

Elliott, John H. et al. (eds.): Memoriales y cartas del Conde Duque de Olivares, Madrid 1978 (Tesis Alfaguara 4), vol. 1: Política interior: 1621 a 1627.

González Palencia, Ángel (ed.): Diego Saavedra Fajardo: Obras completas, Madrid 1946.

Gracián, Baltasar: Obras Completas: Edición y estudio preliminar de Miguel Batllori y Ceferino Peralta, Madrid 1969 (Biblioteca de autores españoles 229), vol. 1: El Héroe – El Político – El Discreto – Oráculo Manual.

Oschmann, Antje (ed.): Acta Pacis Westphalicae, Serie III, Abt. B: Verhandlungsakten, vol. 1: Die Friedensverträge mit Frankreich und Schweden, Teil 1: Urkunden, Münster 1998.

Saavedra Fajardo, Diego de: Empresas políticas, ed. Sagrario López Poza, Madrid 1999 (Letras hispánicas 455).

Bibliography

Ågren, Kurt: The reduktion, in: Michael Roberts (ed.): Sweden's Age of Greatness: 1632–1718, London 1973, pp. 237–264.

Ahnlund, Nils: Dominium maris baltici, in: Nils Ahnlund (ed.): Tradition och historia, Stockholm 1956, pp. 114–130.

Alcalá-Zamora y Queipo de Llano, José: En torno a los planteamientos hegemónicos de la monarquía hispana de los Felipes, in: Revista de la Universidad de Madrid 19 (1970), pp. 57–106.

Arrieta, Jon: Forms of Union: Britain and Spain, a Comparative Analysis, in: Jon Arrieta et al. (eds.): Forms of Union: the British and Spanish Monarchies in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Donostia 2009 (Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos, Cuadernos 5), pp. 23–52.

Aznar, Daniel et al. (eds.): À la place du roi: Vice-rois, gouverneurs et ambassadeurs dans les monarchies française et espagnole (XVIe–XVIIIe siècles), Madrid 2014 (Collection de la Casa de Velázquez 144).

Bosbach, Franz: Monarchia Universalis: Ein politischer Leitbegriff der Frühen Neuzeit, Göttingen 1988 (Schriftenreihe der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 32). URL: https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00047491-8 [2022-08-26]

Brendecke, Arndt: Imperium und Empire: Funktionen des Wissens in der spanischen Kolonialherrschaft, Köln 2009.

Burkhardt, Johannes: Der Dreißigjährige Krieg, Frankfurt am Main 1992 (Edition Suhrkamp 1542, N. F. 542).

Burkhardt, Johannes: Die Friedlosigkeit der Frühen Neuzeit: Grundlegung einer Theorie der Bellizität Europas, in: Zeitschrift für Historische Forschung 24,4 (1997), pp. 509–574. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43572034 [2022-08-26]

Burkhardt, Johannes: Das größte Friedenswerk der Neuzeit: Der Westfälische Frieden in neuer Perspektive, in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 49,10 (1998), pp. 592–612.

Burkhardt, Johannes: Imperiales Denken im Dreißigjährigen Krieg, in: Franz Bosbach et al. (eds.): Imperium/Empire/Reich: Ein Konzept politischer Herrschaft im deutsch-britischen Vergleich: An Anglo-German Comparison of a Concept of Rule, München 1999 (Prinz-Albert-Studien 16), pp. 59–68. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110954432-008 [2022-08-26]

Duchhardt, Heinz: Balance of Power und Pentarchie: Internationale Beziehungen 1700–1785, Paderborn 1997 (Handbuch der Geschichte der Internationalen Beziehungen 4).

Edelmayer, Friedrich: Art. "Personalunion", in: Enzyklopädie der Neuzeit 9 (2009), cols. 996–1002. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2352-0248_edn_COM_325790 [2022-08-26]

Elliott, John H.: The Count-Duke of Olivares: The Statesman in an Age of Decline, New Haven 1986.

Elliott, John H.: A Europe of Composite Monarchies, in: Past and Present 137,1 (1992), pp. 48–71. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/past/137.1.48 [2022-08-26]

Eng, Torbjörn: Det svenska väldet: ett konglomerat av uttrycksformer och begrepp från Vasa till Bernadotte, Uppsala 2001 (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: Studia historica Upsaliensia 201).

Faber, Martin: Absolutismus ist doch ein Quellenbegriff! Zum Auftauchen des Wortes im 18. Jahrhundert in Polen und zu den Konsequenzen für die Absolutismus-Debatte, in: Zeitschrift für Historische Forschung 44,4 (2017), pp. 635–659. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26647852 [2022-08-26]

Floristán Imízcoz, Alfredo: Tramas de integración en la conformación de monarquías compuestas: Los casos británico y español (siglos XVI–XVII), in: José Manuel Azcona et al. (eds.): España en la era global (1492–1898), Madrid 2017, pp. 153–182.

Fur, Gunlög: Colonialism in the Margins: Cultural Encounters in New Sweden and Lapland, Leiden 2006 (The Atlantic World 9).

García García, Bernardo José: La Pax Hispanica: Política exterior del Duque de Lerma, Leuven 1996 (Avisos de Flandes 5). URL: https://lup.be/products/99563 [2022-08-26]

Gil Pujol, Xavier: Visió europea de la monarquia espanyola com a monarquia composta, segles XVI i XVII, in: Recerques 32 (1995), pp. 19–43. URL: http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Recerques/article/view/137740 [2022-08-26]

Goetze, Dorothée: "es so viel seye, alß wann das Reich angegriffen were" – Das Auftreten Schwedens beim Immerwährenden Reichstag im schwedisch-brandenburgischen Krieg, in: Harriet Rudolph et al. (eds.): Reichsstadt – Reich – Europa: Neue Perspektiven auf den Immerwährenden Reichstag zu Regensburg (1663–1806), Regensburg 2015, pp. 195–214.

Goetze, Dorothée: Die Last der Besatzung: Occupatio als fiskalpolitisches Druckmittel: Zur Funktion der festen Plätze in der schwedischen Kriegsstrategie im Reich, in: Inken Schmidt-Voges et al. (eds.): Mit Schweden verbündet – von Schweden besetzt: Akteure, Praktiken und Wahrnehmungen schwedischer Herrschaft im Alten Reich während des Dreißigjährigen Krieges, Hamburg 2016 (Schriftenreihe der David-Mevius-Gesellschaft 10), pp. 11–31.

Goetze, Dorothée: Desintegration im Ostseeraum – Integration ins Reich? Die Vertretung der schwedischen Herzogtümer beim Immerwährenden Reichstag während des Großen Nordischen Krieges (1700–1721) am Beispiel des Corpus Evangelicorum, in: Beate-Christine Fiedler et al. (eds.): Friedensordnungen und machtpolitische Rivalitäten: Die schwedischen Besitzungen in Niedersachsen im europäischen Kontext zwischen 1648 und 1721, Göttingen 2019 (Veröffentlichungen des Niedersächsischen Landesarchivs 3), pp. 126–148.

Goetze, Dorothée: "wider [die] ungerechten Feinde" – Die Besetzung des Herzogtums Bremen 1712 im Spiegel des Aktenmaterials zum Immerwährenden Reichstag, in: Stader Jahrbuch (2019), pp. 31–47.

Goetze, Dorothée: "Particulier-Interesse dem allgemeinen Besten sacrificiret": Die Akteure des Großen Nordischen Krieges beim Immerwährenden Reichstag zwischen Reichs- und Eigeninteresse, in: Historisches Jahrbuch 140 (2020), pp. 383–411.

Goetze, Dorothée: Managing Legal Pluralism: the Negotiations on the re-acquisition of Crown Land in the Livonian Diet (1681) as a Matter of Securitisation and Imperial Integration, in: Journal of the British Academy 9 (2021), pp. 90–111. URL: https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/009s4.090 [2022-08-26]

Gustafsson, Harald: The Conglomerate State: A Perspective on State Formation in Early Modern Europe, in: Scandinavian Journal of History 23,3–4 (1998), pp. 189–213. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/03468759850115954 [2022-08-26]

Gustafsson, Harald: Gamla riken, nya stater: Staatsbildning, politisk kultur och identiteter under Kalmarunionens upplösningsskede 1512–1541, Stockholm 2000.

Härter, Karl: Das Heilige Römische Reich deutscher Nation als mehrschichtiges Rechtssystem, 1495–1806, in: Stephan Wendehorst (ed.): Die Anatomie frühneuzeitlicher Imperien: Herrschaftsmanagement jenseits von Staat und Nation: Institutionen, Personal und Techniken, Berlin 2015 (bibliothek altes reich 5), pp. 327–347. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783486839425.327 [2022-08-26]

Jörn, Nils et al. (eds.): Vom Löwen zum Adler: Der Übergang Schwedisch-Pommerns an Preußen 1815, Göttingen 2019 (Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern 52). URL: https://doi.org/10.7788/9783412512583 [2022-08-26]

Jorzick, Regine: Herrschaftssymbolik und Staat: Die Vermittlung königlicher Herrschaft im Spanien der frühen Neuzeit (1556–1598), Wien 1998 (Studien zur Geschichte und Kultur der iberischen und iberoamerikanischen Länder 4).

Jover Zamora, José María: Sobre los conceptos de monarquía y nación en el pensamiento político español del XVII, in: Cuadernos de Historia de España 13 (1950), pp. 101–150.

Kampmann, Christoph: Universalismus und Staatenvielfalt: Zur europäischen Identität in der frühen Neuzeit, in: Jörg A. Schlumberger et al. (eds.): Europa – aber was ist es? Aspekte seiner Identität in interdisziplinärer Sicht, Köln 1994 (Bayreuther Historische Kolloquien 8), pp. 45–76.

Kennedy, Paul: Aufstieg und Fall der großen Mächte: Ökonomischer Wandel und militärischer Konflikt von 1500 bis 2000, Frankfurt am Main 1992 (Fischer-Taschenbücher 10937).

Koenigsberger, Helmut G.: Dominium Regale or Dominium Politicum et Regale: Monarchies and Parliaments in Early Modern Europe, in: Helmut G. Koenigsberger: Politicians and Virtuosi: Essays in Early Modern History, London 1986 (History series 49), pp. 1–25.

Koenigsberger, Helmut G.: Zusammengesetzte Staaten, Repräsentativversammlungen und der amerikanische Unabhängigkeitskrieg, in: Zeitschrift für Historische Forschung 18,4 (1991), pp. 399–423. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43568190 [2022-08-26]

Kumar, Krishan: Visions of Empire: How Five Imperial Regimes Shaped the World, Princeton 2017. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc773dq [2022-08-26]

Loit, Aleksander: Die Konzeption der schwedischen Herrschaft im Baltikum in der deutsch-baltischen Geschichtsschreibung, in: Латвийский государственныий университет (1985), pp. 26–51.

Lundkvist, Sven: Die schwedischen Kriegs- und Friedensziele 1632–1648, in: Konrad Repgen (ed.): Krieg und Politik 1618–1648, München 1988 (Schriften des Historischen Kollegs: Kolloquien 8), pp. 219–240.

Lundkvist, Sven: Die schwedischen Friedenskonzeptionen und ihre Umsetzung in Osnabrück, in: Heinz Duchhardt (ed.): Der Westfälische Frieden: Diplomatie – politische Zäsur – kulturelles Umfeld – Rezeptionsgeschichte, München 1998 (Historische Zeitschrift, Beihefte N. F. 26), pp. 349–359. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20523016 [2022-08-26]

Monostori, Tibor: Saavedra Fajardo and the Myth of Ingenious Habsburg Diplomacy: A New Political Biography and Sourcebook (1637–1646), A Coruña 2019.

Neuhaus, Helmut: Das Reich in der Frühen Neuzeit, 2. Aufl., München 2003 (Enzyklopädie Deutscher Geschichte 42).

Olesen, Jens E.: The Struggle for Supremacy in the Baltic Between Denmark and Sweden, 1563–1721, in: Erkki I. Kouri et al. (eds.): The Cambridge History of Scandinavia, Cambridge 2016, vol. 2: 1520–1870, pp. 246–267. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139031639.016 [2022-08-26]

Pagden, Anthony: Lords of all the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain and France c.1500–c.1800, New Haven 1995, pp. 103–125.

Parker, Geoffrey: Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century, New Haven 2014. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt32bksk [2022-08-26]

Rauschenbach, Sina et al. (eds.): Reforming Early Modern Monarchies: The Castilian Arbitristas in Comparative European Perspectives, Wiesbaden 2016 (Wolfenbütteler Forschungen 143).

Rexheuser, Rex (ed.): Die Personalunionen von Sachsen-Polen 1697–1763 und Hannover-England 1714–1837: Ein Vergleich, Wiesbaden 2005 (Deutsches Historisches Institut Warschau: Quellen und Studien 18).

Rivero Rodríguez, Manuel: La monarquía de los Austrias: Historia del Imperio español, Madrid 2017.

Roberts, Michael: The Swedish Imperial Experience, 1560–1718, Cambridge 1992 (Wiles Lectures 1977).

Rohrschneider, Michael: Außenpolitische Strukturprobleme frühneuzeitlicher Mehrfachherrschaften – Brandenburg-Preußen und Spanien im Vergleich, in: Jürgen Frölich et al. (eds.): Preußen und Preußentum vom 17. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart: Beiträge des Kolloquiums aus Anlaß des 65. Geburtstages von Ernst Opgenoorth am 12.02.2001, Berlin 2002, pp. 55–69.

Rohrschneider, Michael: Die Statthalter des Großen Kurfürsten als außenpolitische Akteure, in: Michael Kaiser et al. (eds.): Membra unius capitis: Studien zu Herrschaftsauffassungen und Regierungspraxis in Kurbrandenburg (1640–1688), Berlin 2005 (Forschungen zur brandenburgischen und preussischen Geschichte N. F., Beiheft 7), pp. 213–234. URL: https://doi.org/10.3790/978-3-428-51790-9 [2022-08-26]

Rohrschneider, Michael: Der gescheiterte Frieden von Münster: Spaniens Ringen mit Frankreich auf dem Westfälischen Friedenskongress (1643–1649), Münster 2007 (Schriftenreihe der Vereinigung zur Erforschung der Neueren Geschichte e. V. 30).

Rohrschneider, Michael: Zusammengesetzte Staatlichkeit in der Frühen Neuzeit: Aspekte und Perspektiven der neueren Forschung am Beispiel Brandenburg-Preußens, in: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 90 (2008), pp. 321–349. URL: https://doi.org/10.7788/akg.2008.90.2.321 [2022-08-26]

Rohrschneider, Michael: Der universale Frieden als Leitvorstellung auf dem Westfälischen Friedenskongress (1643–1649): Probleme und Perspektiven der Forschung, in: Peter Geiss et al. (eds.): Eine Werteordnung für die Welt? Universalismus in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Baden-Baden 2019, pp. 195–216. URL: https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845295176-195 [2022-08-26]

Rystad, Göran: Empire-Building and Social Transformation – Sweden in the 17th Century, in: Klaus-Richard Böhme et al. (eds.): 1648 and European Security Proceedings, Stockholm October 15–16, 1998, Stockholm 1999 (Försvarshögskolans acta. B, Strategiska institutionen 10), pp. 167–177.

Rystad, Göran: Expansion and Social Transformation: Sweden's Great Power Experience, in: Lars Andersson (ed.): The Vasa Dynasty and the Baltic Region: Politics, Religion and Culture 1560–1660: A Symposium at Kalmar Castle, February 4–6 2000, Kalmar 2003, pp. 61–68.

Schilling, Lothar (ed.): Absolutismus, ein unersetzliches Forschungskonzept? Eine deutsch-französische Bilanz, München 2008 (Pariser historische Studien 79). URL: https://doi.org/10.1524/9783486841329 [2022-08-26]

Schmidt, Peer: Spanische Universalmonarchie oder "teutsche Libertet": Das spanische Imperium in der Propaganda des Dreißigjährigen Krieges, Stuttgart 2001 (Studien zur modernen Geschichte 54).

Schmidt, Peer: Die Reiche der spanischen Krone: Konflikte um die Reichseinheit in der frühneuzeitlichen spanischen Monarchie, in: Hans-Jürgen Becker (ed.): Zusammengesetzte Staatlichkeit in der Europäischen Verfassungsgeschichte. Tagung der Vereinigung für Verfassungsgeschichte im Hofgeismar vom 19.3.–21.3.2001, Berlin 2006 (Beihefte zu "Der Staat", 16), pp. 171–196.

Schmidt-Voges, Inken: De antiqua claritate et clara antiquitate Gothorum: Gotizismus als Identitätsmodell im frühneuzeitlichen Schweden, Frankfurt am Main 2004 (Imaginatio borealis 4).

Schmidt-Voges, Inken: Art. "Gotizismus", in: Enzyklopädie der Neuzeit 4 (2006), cols. 1000–1002. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2352-0248_edn_SIM_275191 [2022-08-26]

Strohmeyer, Arno: Ideas of Peace in Early Modern Models of International Order: Universal Monarchy and Balance of Power in Comparison, in: Jost Dülffer et al. (eds.): Peace, War and Gender from Antiquity to the Present: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, Essen 2009 (Frieden und Krieg 14), pp. 65–80.

Tölle, Tom: Early Modern Empires: An Introduction to the Recent Literature, in: H-Soz-Kult, 20.04.2018. URL: http://hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de/forum/2018-04-001 [2022-08-26]

Tuchtenhagen, Ralph: Zentralstaat und Provinz im frühneuzeitlichen Nordosteuropa, Wiesbaden 2008 (Veröffentlichungen des Nordost-Instituts 5).

Weber, Hermann: Chrétienté et équilibre européen dans la politique du Cardinal de Richelieu, in: XVIIe Siècle 42 (1990), pp. 7–16.

Weise, Johannes: Die Integration Schwedisch-Pommerns in den preußischen Staatsverband: Transformationsprozesse innerhalb von Staat und Gesellschaft, München 2005.

Wendehorst, Stephan: Altes Reich, "Alte Reiche" und der imperial turn in der Geschichtswissenschaft, in: Stephan Wendehorst (ed.): Die Anatomie frühneuzeitlicher Imperien: Herrschaftsmanagement jenseits von Staat und Nation: Institutionen, Personal und Techniken, Berlin 2015 (bibliothek altes reich 5), pp. 17–58. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783486839425.17 [2022-08-26]

Wiebensohn, Anke: Die Integration Wismars in das Herzogtum Mecklenburg 1803, Hamburg 2015 (Schriftenreihe der David-Mevius-Gesellschaft 9).

Zellhuber, Andreas: Der gotische Weg in den deutschen Krieg – Gustav Adolf und der schwedische Gotizismus, Augsburg 2002 (Documenta Augustana 10).

Notes

- ^ The terminus technicus "composite state" (or "composite monarchy") is firmly established in scholarship in spite of a number of plausible conceptual alternatives – notably "conglomerate state" or "polycentric state" – having been proposed. In addition, the term Mehrfachherrschaft has become established in German scholarship, monarchie plurielle in French, monarquia compuesta or monarchia agregada in Spanish and konglomeratstat in Swedish. On the terminology see Edelmayer, Personalunion 2009, col. 996; for konglomeratstat see Gustafsson, Conglomerate State 1998.

- ^ See esp. Koenigsberger, Dominium Regale 1986; Koenigsberger, Zusammengesetzte Staaten 1991; Elliott, Composite Monarchies 1992.

- ^ For a comparative perspective on Brandenburg-Prussia and Spain in the early modern age see Rohrschneider, Außenpolitische Strukturprobleme 2002.

- ^ For such approaches see Wendehorst, Altes Reich 2015, pp. 18f., and Tölle, Early Modern Empires 2018, pp. 13f.

- ^ See Tölle, Early modern Empires 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Kumar, Visions of Empire, p. 7. Similarly Wendehorst, Altes Reich, pp. 25f.; with a focus on early modern empires Tölle, Early modern Empires 2018, pp. 13–26.

- ^ See Wendehorst, Altes Reich, pp. 26f.

- ^ See Tölle, Early modern Empires 2018, pp. 16–24. Drawing on the scholarship on the subject, Tölle develops the defining traits of empires as follows: 1) expansive character; 2) centre/periphery distinction; 3) selective integration of different population groups; 4) strong loyalty among elites and marginalised groups; 5) integrative power of charismatic individuals; 6) lack of participative institutions; 7) confessional unification; 8) sense of historical or imperial mission; 9) tolerance of linguistic and ethnic diversity.

- ^ See esp. Schilling, Absolutismus 2008; Faber, Absolutismus 2017.

- ^ For detailed accounts see Rohrschneider, Statthalter 2005; Aznar, À la place du roi 2014.

- ^ See Pagden, Lords of all the World 1995.

- ^ For foundational studies on monarchia universalis see Bosbach, Monarchia Universalis 1988; Schmidt, Spanische Universalmonarchie 2001.

- ^ See Burkhardt, Der Dreißigjährige Krieg 1992, pp. 30–63.

- ^ See Rohrschneider, Zusammengesetzte Staatlichkeit 2008, pp. 332–340.

- ^ For a critical appraisal of the term "Habsburg embrace" (habsburgische Umklammerung) see Burkhardt, Friedenswerk 1998, p. 595.

- ^ An illustrative example is offered by the political testaments of the Hohenzollerns; see Rohrschneider, Zusammengesetzte Staatlichkeit 2008.

- ^ Recently Rohrschneider, Der universale Frieden 2019; also Strohmeyer, Ideas of Peace 2009.

- ^ The pax austriaca pursued by Spain in the 17th century was accordingly supposed to be dominated by the two lines of the casa de Austria, the King of Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor. On the concept of pax austriaca see Kampmann, Universalismus und Staatenvielfalt 1994, p. 64; García García, Pax Hispanica 1996, p. 88; Rohrschneider, Der gescheiterte Frieden 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Tölle, Early Modern Empires 2018, p. 30.

- ^ See Brendecke, Imperium und Empirie 2009.

- ^ See e.g. Jorzick, Herrschaftssymbolik 1998.

- ^ A representative case is Wendehorst, Altes Reich 2015, p. 18.

- ^ Neuhaus, Reich 2003, p. 2.

- ^ Härter, Rechtssystem 2015, p. 330.

- ^ Although numerous studies exist highlighting the specifics of early modern state formation in both empires with particular regard to its "composite" nature, scholarship has not yet fully explored the many insights to be gained from a comparative approach. For good examples of the latter see Rexheuser, Personalunionen 2005; Arrieta, Forms of Union 2009; Floristán Imízcoz, Tramas de integración 2017.

- ^ See generally Burkhardt, Friedlosigkeit 1997.

- ^ See Duchhardt, Balance of Power und Pentarchie 1997, pp. 166–176.

- ^ For a familiar example see Kennedy, Aufstieg und Fall 1992.

- ^ On Gothicism see Zellhuber, Gotizismus 2002; Schmidt-Voges, Identitätsmodell 2004; Schmidt-Voges, Gotizismus 2006.

- ^ Sweden in 1681 extended from the Swedish heartlands bordering on Denmark and Norway through Finland, Ingria, Karelia and Kexholm. It also included Estonia and Livonia as well as the territories within the Holy Roman Empire south of the Baltic Sea: Western Pomerania, Bremen, Verden and Zweibrücken. The city of Wismar had also become part of the Swedish composite state in 1648.

- ^ On Swedish expansion see Rystad, Expansion 2003; Roberts, Experience 1992, pp. 1–42; Olesen, Struggle 2016. On the Swedish colonies in particular see Fur, Colonialism 2006.

- ^ See Roberts, Experience 1992.

- ^ Besides its acquisitions in the Scandinavian Peninsula of 1658/1660 (Scania, Blekinge and Trondheims län), Sweden retained only the part of Western Pomerania to the north of the river Peene and the city of Wismar. Western Pomerania ceased to be part of the Swedish composite state in 1815, the city of Wismar had already done so de facto in 1803. See Wiebensohn, Integration 2015; Weise, Integration 2005; Jörn, Löwen 2019. Sweden did not formally renounce its claim to Wismar until 1903.

- ^ Roberts, Experience 1992, p. 2.

- ^ See Eng, Väldet 2001, pp. 238–247.

- ^ Schmidt-Voges, Gotizismus 2006, col. 1000.

- ^ On the collapse of the Kalmar Union and the formation of Sweden as an independent kingdom see Gustafsson, Riken 2000.

- ^ Schmidt-Voges, Identitätsmodell 2004, pp. 254–262; quotation on p. 262.

- ^ See Schmidt-Voges, Identitätsmodell 2004, pp. 266–271.

- ^ See Ahnlund, Dominium, p. 118.

- ^ See Ahnlund, Dominium , pp. 118f.

- ^ See Goetze, Besatzung 2016, pp. 17–21; Lundkvist, Kriegs- und Friedensziele 1988; Lundkvist, Friedenskonzeptionen 1998.

- ^ See Ågren, Reduktion 1973; Goetze, Pluralism 2021.

- ^ See Loit, Konzeption 1985.

- ^ Tuchtenhagen, Zentralstaat 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Tuchtenhagen, Zentralstaat 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Tuchtenhagen, Zentralstaat 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Eng, Väldet 2001, p. 251.

- ^ Art. X,9 Instrumentum Pacis Osnabrugensis, in: Oschmann, Acta Pacis Westphalicae 1998, no. 18, p. 135.

- ^ See Goetze, Auftreten 2015; Goetze, Desintegration 2019; Goetze, Feinde 2019; Goetze, Particulier-Interesse 2020.

- ^ See Eng, Väldet 2001, pp. 251–253.

- ^ See Eng, Väldet 2001, pp. 247–249.

- ^ Tuchtenhagen, Zentralstaat 2008, pp. 95–101.

- ^ Rystad, Empire-Building 1999, p. 172.

- ^ For an overview see Gil Pujol, Visió europea 1995; Schmidt, Reiche 2006; Rivero Rodríguez, Monarquía 2017; Kumar, Visions of Empire 2017, pp. 145–212; on the following see Rohrschneider, Außenpolitische Strukturprobleme 2002, pp. 59–64; Rohrschneider, Der gescheiterte Frieden 2007, pp. 32–50.

- ^ The king of Spain's realms included Castile, León, Navarre, Portugal and Aragón (including Valencia, the Principality of Barcelona, the Balearic Islands and Aragón's Italian possessions of Sardinia, Naples and Sicily) as well as Milan, the State of the Presidi, the Spanish Netherlands, the Franche-Comté and – last but by no means least – the overseas colonies.

- ^ See Burkhardt, Imperiales Denken 1999.

- ^ For a short account of his life and work see Rohrschneider, Der gescheiterte Frieden 2007, pp. 145–152, which contains further biographical information; see also most recently Monostori, Saavedra Fajardo 2019.

- ^ This was visually emphasised with the image of an arrow shot upwards and which must at some point enter on an inevitable and irreversible decline. See Saavedra Fajardo, Empresas políticas 1999, p. 705.

- ^ See Rohrschneider, Der gescheiterte Frieden 2007, pp. 32–43. In this context, it is worth emphasizing the proposed reforms of the so-called Arbitristas; see recently Rauschenbach, Reforming 2016.

- ^ Experience had shown, according to a letter written by Philip IV in 1626, that so many kingdoms and realms could not be united and sustained under a single crown without warfare. See Alcalá-Zamora y Queipo de Llano, Planteamientos hegemónicos 1970, p. 93.

- ^ See Rohrschneider, Der gescheiterte Frieden 2007, pp. 37f.

- ^ See Rohrschneider, Der gescheiterte Frieden 2007, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Consider e.g. proposals to that effect by the bishop and sometime viceroy of New Spain, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza (1600–1659). See Jover Zamora, Conceptos 1950, p. 144.

- ^ On Richelieu's attitude see Weber, Chrétienté 1990, p. 9.

- ^ See Álamos de Barrientos, Discurso 1990, p. 45.

- ^ See Gracián, Obras 1969, p. 277.

- ^ On the gran memorial see Elliott, Memoriales 1978, pp. 49–100.

- ^ See Elliott, Olivares 1986, pp. 244–277.

- ^ See Parker, Global Crisis 2014, pp. 254–290.

- ^ See Rohrschneider, Der gescheiterte Frieden 2007, p. 205.

- ^ See Rohrschneider, Der gescheiterte Frieden 2007, pp. 291f.

- ^ Text in González Palencia 1946, pp. 705–1068.