Introduction

One of the most elusive institutions of elite society and political culture in European history was the princely court. Seen as the definition of exclusivity, court regulations normally restricted entry to only those of the highest class of nobility; yet access was often granted to people of lower birth if they were talented artists or efficient administrators, or possessed exceptional beauty. The court was often at the centre of emergent senses of national belonging, contrasting in their particular characteristics, yet at the same time they functioned as pan-European spaces, where courtiers, diplomats and travellers could recognise certain shared features no matter where they were.

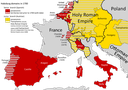

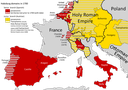

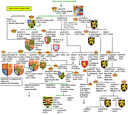

At the heart of the princely court was the concept of 'dynasty'. But this too could be an enigmatic term. Traditional definitions named a dynasty as any group of kin descended from a founding member, usually a male, and bound together with common interests. But in its origins the Greek word δυναστεία (dynastéia) referred specifically to power.1 Yet court nobles also identified with kin that crossed family lines, their maternal cousins, and sometimes felt a stronger affinity with them than with members of their own dynasty. Royal dynasties could hold together a state, or could divide it – sometimes using confessional differences or political ideologies to mark out this division. They could also span across state borders, with royal brides continually crossing borders to marry, or trans-national noble court dynasties often having a branch resident at two or more courts. The royal and princely dynasties, and those of their chief courtiers, thus both represented emerging 'national' senses of belonging and also acted as supra-national entities, connecting courts and nation-states through kinship, such as the Habsburgs in Spain, Austria and the Low Countries in the 16th and 17th centuries ; the Bourbons in France, Spain and Italy in the 18th century; or the Saxe-Coburgs

; the Bourbons in France, Spain and Italy in the 18th century; or the Saxe-Coburgs in Britain, Belgium, Portugal and Bulgaria in the 19th century.

in Britain, Belgium, Portugal and Bulgaria in the 19th century.

This contribution will look at these interlinked concepts of court and dynasty, their commonalities and their contradictions, across the period 1450 to 1918. Both court and dynasty existed long before 1450, and indeed continued after 1918, yet the great era of royal dynasticism on a European scale, as opposed to the more localised versions of the earlier medieval period, ranged from the era of the Italian Renaissance to the cataclysm of the First World War. Much of the chronological focus will be, however, on the 16th to 18th centuries, when dynasticism as a force and the court as an institution were both at their height. This is the era of the magnificence of court culture that reached its apogee at the Versailles of Louis XIV (1638–1715)[ ] but also the persistence of alternative courtly cultures, such as the more reclusive courts of the Habsburgs in 17th-century Madrid or Vienna, or the more austere court cultures in 18th-century London or Berlin. Second-tier courts should not be overlooked, however, and indeed made up a much larger percentage of Europe's courts, from Copenhagen to Munich to Nancy to Parma. In the 19th century many European courts became centres of a ceremonial culture that connected the historical dynasty with the newly emergent nation-state and the identities and aspirations of ordinary people. Yet other courts persisted as havens of exclusivity in which the old union between dynasty and the traditional aristocracy continued to dominate both court and organs of government.2

] but also the persistence of alternative courtly cultures, such as the more reclusive courts of the Habsburgs in 17th-century Madrid or Vienna, or the more austere court cultures in 18th-century London or Berlin. Second-tier courts should not be overlooked, however, and indeed made up a much larger percentage of Europe's courts, from Copenhagen to Munich to Nancy to Parma. In the 19th century many European courts became centres of a ceremonial culture that connected the historical dynasty with the newly emergent nation-state and the identities and aspirations of ordinary people. Yet other courts persisted as havens of exclusivity in which the old union between dynasty and the traditional aristocracy continued to dominate both court and organs of government.2

In order to establish the broadest view of the princely courts of Europe in this period, and to track some of the changes that create such differences, this survey article will first define the court and its key institutions, the household officers. Then it will look at the shift in how dynasties were viewed, or viewed themselves, shifting from an association of living relatives, a horizontal conception of dynasty, to something much more enduring, a more vertical view linking the past, present and future. Finally, it will examine how courtly and dynastic practices were shared, transferred and impacted behaviour in neighbouring courts, from regulating access to the prince to defining who was or was not a member of the ruling dynasty. Once again we will see a fascinating contrast (and co-existence) between territorial and supra-territorial dynasticism, and the persistence of both well into the 20th century. The following overview will focus mostly on the larger, more well-known – and more influential – royal courts of France, Spain and England, the imperial court in Vienna, and those most influenced by these court cultures, such as those in Berlin and St Petersburg.

What is the Court?

The modern conceptualisation of the court formed in the late medieval period from the extension of a prince's household, his domestic servants and his closest friends and advisors. So, although we tend to think of it originally as a place, or a building , it could equally refer to people, those who moved around with the prince in his annual progressions around his kingdom or principality. The court thus always included, from earliest days, by necessity, some elements of government – the chancery, the treasury, the military – to aid the prince in his day-to-day administrative duties. Indeed, the distinction between private domestic spaces and public political administrative duties formed one of the first historiographical debates when the sub-field of history now known as 'court studies' was first developed in the early 1970s. This debate involved the degree to which a 'modern' professionalised bureaucracy was pushing out the aristocratic courtiers in the 16th century as counsellors of monarchs and administrators of their governments. It was assumed that genuine power resided in government, and the court was irrelevant. It is now accepted that while royal governments did indeed become professionalised in this period, there was no sharp divide between commoners acting as public servants in the government and nobles acting as personal advisors to the monarch in his court. Many courtiers were in fact both members of a monarch's private entourage and also involved in the running of the state, as counsellors, diplomats or soldiers.3

, it could equally refer to people, those who moved around with the prince in his annual progressions around his kingdom or principality. The court thus always included, from earliest days, by necessity, some elements of government – the chancery, the treasury, the military – to aid the prince in his day-to-day administrative duties. Indeed, the distinction between private domestic spaces and public political administrative duties formed one of the first historiographical debates when the sub-field of history now known as 'court studies' was first developed in the early 1970s. This debate involved the degree to which a 'modern' professionalised bureaucracy was pushing out the aristocratic courtiers in the 16th century as counsellors of monarchs and administrators of their governments. It was assumed that genuine power resided in government, and the court was irrelevant. It is now accepted that while royal governments did indeed become professionalised in this period, there was no sharp divide between commoners acting as public servants in the government and nobles acting as personal advisors to the monarch in his court. Many courtiers were in fact both members of a monarch's private entourage and also involved in the running of the state, as counsellors, diplomats or soldiers.3

The blur between the private and public needs of the prince also can generate confusion, at least in English, between the royal court and the judiciary court, since both originated from the same place – the space where the prince lived and where he often dispensed justice. The Romans used the word cors to describe an aristocratic residence, derived from the co-hortus, literally a farmyard or enclosure (but also indicated a military retinue, from which the modern word cohort was derived). From cors, the Latin-based languages of Europe developed corte (Italian/Spanish), cour (French) and court (English). The Romans also borrowed a word from the Greeks, aulè, a forecourt or palace, and used it as aula, from which many courtly societies derived the adjective 'aulic' to refer to court offices or ranks. The most well-known of these was the Aulic Council, the personal council of the Holy Roman Emperor, distinct from the general councils of the Imperial princes.4 Other European languages used terms with similar origins to describe the court: hof in German (an enclosure or yard), or dvor in various Slavic languages (a courtyard or manor).

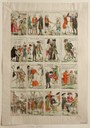

These various words for court point to one of the defining features of court culture, the idea of a 'threshold' of court spaces. Those who had the privilege to cross the threshold into the proximity of the ruling prince were considered the elite of any courtly society.5 Indeed, throughout their long history princely courts were always divided into separate spaces, especially public versus private spaces. The most basic layout of any ruler's residence in medieval Europe was a two-part division between 'hall' (public) and 'chamber' (private). Access to the private areas defined a courtier's status, and this division developed towards the end of the Middle Ages, in the period around 1450, into one of the hallmarks of the early modern court system, the enfilade .6 Royal palaces began to be constructed with long sequences of rooms

.6 Royal palaces began to be constructed with long sequences of rooms , through which courtiers seeking access to the monarch needed to pass. Most people only ever saw the first few rooms, usually starting with a guards chamber – decorated specifically with symbols of military power – then moving to an antechamber where a king's minister could identify whether your grievance or news warranted the attention of the sovereign, then an audience chamber or throne room, in which a prince interacted publicly with his or her subjects. From here, a series of more private spaces were accessible only to those with rights of access due to their high rank, a position in the monarch's government or personal favour. The privy council would occupy one room (a privy chamber), a monarch's personal friends another (a cabinet, perhaps to play cards), and the monarch's more intimate life (the bedchamber) – in later stages of development, the bedchamber was divided between an actual room for sleeping and a more formal chamber where the monarch would be ceremonially be put to bed each night attended by high-ranking courtiers.7 Usually these private spaces were followed by even more private spaces, where the monarch met a mistress, prayed or meditated (an oratory or private chapel), or studied in a library or cabinet of curiosities (a studiolo or kunstkammer)

, through which courtiers seeking access to the monarch needed to pass. Most people only ever saw the first few rooms, usually starting with a guards chamber – decorated specifically with symbols of military power – then moving to an antechamber where a king's minister could identify whether your grievance or news warranted the attention of the sovereign, then an audience chamber or throne room, in which a prince interacted publicly with his or her subjects. From here, a series of more private spaces were accessible only to those with rights of access due to their high rank, a position in the monarch's government or personal favour. The privy council would occupy one room (a privy chamber), a monarch's personal friends another (a cabinet, perhaps to play cards), and the monarch's more intimate life (the bedchamber) – in later stages of development, the bedchamber was divided between an actual room for sleeping and a more formal chamber where the monarch would be ceremonially be put to bed each night attended by high-ranking courtiers.7 Usually these private spaces were followed by even more private spaces, where the monarch met a mistress, prayed or meditated (an oratory or private chapel), or studied in a library or cabinet of curiosities (a studiolo or kunstkammer) . Many great nobles also developed a similar layout for their palaces or country houses, for example Chatsworth for the dukes of Devonshire in England, or Schloss Eggenberg for the Eggenberg princes in Austria

. Many great nobles also developed a similar layout for their palaces or country houses, for example Chatsworth for the dukes of Devonshire in England, or Schloss Eggenberg for the Eggenberg princes in Austria .

.

These spaces in the enfilade, ranging from public to private, were regulated by different officers of the court. They went by different names in the various courts of Europe, and sometimes varied in precise functions, but in general, most courts had the same basic structures.8 The initial division was between inside and outside spaces, and a tripartite division between Master of the Household (or Steward), Master of the Bedchamber (Chamberlain) and Master of the Horse (or Equerry). Sitting slightly outside this structure was the military household, made up of various units of elite guards, which had elements both inside and outside the palace.9

Inside the palace, the more public aspects of a monarch's daily life were looked after by the Grand Master of the Household (known as the Lord Steward in England and Scotland, the Mayordomo mayor in Spain, the Obersthofmarschall in German courts). The Master of the Household ensured there was food on the table, entertainment for the prince, and maintenance of the building. He was thus in charge of subsidiary offices like the head of the kitchens, or the master of revels. In some courts there was a specific Master of the Table (or more colourfully, the bouche or mouth), primarily in Valois Burgundy and its successor, Habsburg Spain; a Grand Butler, or a Grand Sommelier (in charge of the wine!); and other food-related officers such as the Grand Pantler (in charge of food storage, specifically pain, or bread). The more private areas of the court were the domain of the Grand Chamberlain (or Lord Chamberlain; Oberstkämmerer in German; Camerlengo or Camarera in Italian and Spanish), whose symbol of office, the crossed keys, represented his authority visually : anyone who wished to cross over from the public to the private spaces within the court usually needed approval of the Chamberlain.10 Within the Chamberlain's domain were subsidiary officers such as the Master of the Wardrobe, who looked after a prince's clothing, and others who attended the monarch's daily needs like the Premier Gentleman of the Chamber or the Premier Valet. The Chamberlain's department usually also included the royal physicians and a treasury officer like the English Keeper of the Privy Purse, stemming from the tradition from the earliest days when a prince's private wealth was stored in a locked chest in his bedchamber – the most secure space in the royal dwelling. There was usually a female equivalent to these officers: the Superintendent of the Queen's Household

: anyone who wished to cross over from the public to the private spaces within the court usually needed approval of the Chamberlain.10 Within the Chamberlain's domain were subsidiary officers such as the Master of the Wardrobe, who looked after a prince's clothing, and others who attended the monarch's daily needs like the Premier Gentleman of the Chamber or the Premier Valet. The Chamberlain's department usually also included the royal physicians and a treasury officer like the English Keeper of the Privy Purse, stemming from the tradition from the earliest days when a prince's private wealth was stored in a locked chest in his bedchamber – the most secure space in the royal dwelling. There was usually a female equivalent to these officers: the Superintendent of the Queen's Household or the Première Dame d'honneur overseeing the running of the consort's household in France; the First Lady of the Bedchamber in England; the Camarera mayor in Spain. The separate space occupied by a queen-consort could often become an alternative political space, seen as foreign and potentially dangerous.11

or the Première Dame d'honneur overseeing the running of the consort's household in France; the First Lady of the Bedchamber in England; the Camarera mayor in Spain. The separate space occupied by a queen-consort could often become an alternative political space, seen as foreign and potentially dangerous.11

When the monarch ventured outside the royal residence, he or she was looked after by the Master of the Horse, the Master of the Hunt and various officers of the military (the Grand Constable, the Grand Admiral, or similar). In France, the Master of the Horse (known as the Grand Écuyer) accompanied the king wherever he went outside the palace, organised his horses for hunting or for war, or carriages for longer journeys. He bore the sword of state at major ceremonies like the coronation, which he helped organise.12 In England this office and that of Earl Marshal became separated, and both had duties looking after the Royal Stables and organising major rituals of state such as royal funerals.13 In German lands, this officer was known as the Oberststallmeister, and in Spain the Caballerizo mayor. Most courts also had a Master of Ceremonies, whose duties were regulating public events such as royal entrées or diplomatic receptions, and a head of the ecclesiastical household – a Grand Almoner or a Head Chaplain. It is interesting when studying the history of the court to see how certain aspects of court culture were divided or overlapped between jurisdictions of these various court offices: for example, musicians were often divided between 'inside' instruments (such as violins) within the department of the Chamberlain, and 'outside' instruments (like trumpets) who were employed by the Master of the Horse, and those who served specifically in the royal chapel.14 There were other powerful individuals known as 'grand officers of the crown' or 'great officers of state', who had left the confines of the prince's residence early on in the Middle Ages and became professionalised – in other words, these were often held by trained administrators (often clergy or lawyers) rather than grand aristocrats. This mostly refers to the Grand or Lord Chancellor and his deputy the Keeper of the Seals.

or for war, or carriages for longer journeys. He bore the sword of state at major ceremonies like the coronation, which he helped organise.12 In England this office and that of Earl Marshal became separated, and both had duties looking after the Royal Stables and organising major rituals of state such as royal funerals.13 In German lands, this officer was known as the Oberststallmeister, and in Spain the Caballerizo mayor. Most courts also had a Master of Ceremonies, whose duties were regulating public events such as royal entrées or diplomatic receptions, and a head of the ecclesiastical household – a Grand Almoner or a Head Chaplain. It is interesting when studying the history of the court to see how certain aspects of court culture were divided or overlapped between jurisdictions of these various court offices: for example, musicians were often divided between 'inside' instruments (such as violins) within the department of the Chamberlain, and 'outside' instruments (like trumpets) who were employed by the Master of the Horse, and those who served specifically in the royal chapel.14 There were other powerful individuals known as 'grand officers of the crown' or 'great officers of state', who had left the confines of the prince's residence early on in the Middle Ages and became professionalised – in other words, these were often held by trained administrators (often clergy or lawyers) rather than grand aristocrats. This mostly refers to the Grand or Lord Chancellor and his deputy the Keeper of the Seals.

All of these offices provided positions of service and honour to the nobilities of their respective kingdoms. Nobles flocked to the court to get positions for their sons or daughters in the royal household, as pages, valets or equerries, or as maids of honour. If they got noticed, they could then launch successful careers in the military or diplomatic corps, or forge successful marriage alliances to promote both their and their family's position within aristocratic society . If a courtier of either gender was particularly successful, they could obtain positions of great prestige and power, such as Grand Chamberlain or First Lady of the Household. These offices were appointed by a monarch to serve him, but by the end of the 17th century, certain court families had established an almost hereditary hold on these posts. In France, the House of Lorraine controlled the office of Master of the Horse from 1643 to the end of the Ancien Régime, while the office of Grand Chamberlain was held by the La Tour d'Auvergne family for much of the same period.15 In England, the job of Lord Chamberlain was held by the de Vere family, earls of Oxford, from the 12th century until their extinction in 1626, when it was deemed a fully hereditary office and passed to the next heir, Baron Willoughby de Eresby. By the 18th century, this hereditary hold over the office had become so entrenched that when Lord Willoughby's direct line ended in 1779, the job became 'shared', held in alternating reigns by his co-heirs. A similar example can be seen in Spain, where the office of Constable of Castile was held by the Fernández de Velasco family, dukes of Frías, from 1473 until 1713 when the title was suppressed. What this meant in practice for many of the grand monarchies of Europe was that, by the 18th century, court officers whose function had been initially designed to serve the dynasty were now quite often in charge of regulating the affairs of the dynasty – the 'gilded cage' idea of the high nobility at Versailles in the late 18th century had in fact been turned on its head, and monarchs like Louis XVI (1754–1793) could do nothing without the approval of their senior courtiers.16

. If a courtier of either gender was particularly successful, they could obtain positions of great prestige and power, such as Grand Chamberlain or First Lady of the Household. These offices were appointed by a monarch to serve him, but by the end of the 17th century, certain court families had established an almost hereditary hold on these posts. In France, the House of Lorraine controlled the office of Master of the Horse from 1643 to the end of the Ancien Régime, while the office of Grand Chamberlain was held by the La Tour d'Auvergne family for much of the same period.15 In England, the job of Lord Chamberlain was held by the de Vere family, earls of Oxford, from the 12th century until their extinction in 1626, when it was deemed a fully hereditary office and passed to the next heir, Baron Willoughby de Eresby. By the 18th century, this hereditary hold over the office had become so entrenched that when Lord Willoughby's direct line ended in 1779, the job became 'shared', held in alternating reigns by his co-heirs. A similar example can be seen in Spain, where the office of Constable of Castile was held by the Fernández de Velasco family, dukes of Frías, from 1473 until 1713 when the title was suppressed. What this meant in practice for many of the grand monarchies of Europe was that, by the 18th century, court officers whose function had been initially designed to serve the dynasty were now quite often in charge of regulating the affairs of the dynasty – the 'gilded cage' idea of the high nobility at Versailles in the late 18th century had in fact been turned on its head, and monarchs like Louis XVI (1754–1793) could do nothing without the approval of their senior courtiers.16

By this point, monarchs were often kept on a tighter leash financially – especially in Great Britain, where after 1760 King George III (1738–1820)[ ] agreed to surrender his hereditary revenues from the Crown Estate to Parliament, in return for Parliament assuming responsibility for most of the costs of the civil government and paying an annual stipend to the members of the royal family.17 But even after this concession, the general public became increasingly disinterested in financing the extravagant lifestyles of a growing number of royals all claiming to be members of the royal dynasty

] agreed to surrender his hereditary revenues from the Crown Estate to Parliament, in return for Parliament assuming responsibility for most of the costs of the civil government and paying an annual stipend to the members of the royal family.17 But even after this concession, the general public became increasingly disinterested in financing the extravagant lifestyles of a growing number of royals all claiming to be members of the royal dynasty . Of well-known 18th-century monarchs, Philip V of Spain (1683–1746) produced ten children; Maria Theresa of Austria (1717–1780)[

. Of well-known 18th-century monarchs, Philip V of Spain (1683–1746) produced ten children; Maria Theresa of Austria (1717–1780)[ ] sixteen; while George III had fifteen children, of whom all but two survived into adulthood and required funds for the establishment of households, dowries and other living expenses.18 Maria Theresia highlighted the issue by insisting, from the 1750s, that all of her children be addressed as Royal Highness and treated as royal princes by visiting dignitaries.19 With so many fully royal members at court, many who then had children of their own, it became necessary to re-define what was meant by the royal dynasty.

] sixteen; while George III had fifteen children, of whom all but two survived into adulthood and required funds for the establishment of households, dowries and other living expenses.18 Maria Theresia highlighted the issue by insisting, from the 1750s, that all of her children be addressed as Royal Highness and treated as royal princes by visiting dignitaries.19 With so many fully royal members at court, many who then had children of their own, it became necessary to re-define what was meant by the royal dynasty.

What is the Dynasty?

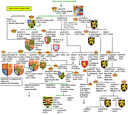

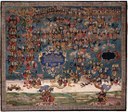

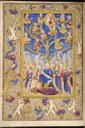

In the Middle Ages, monarchs and their leading court nobles sometimes went to great expense to commission elaborate illustrated genealogies . These usually took the form of the image of a tree, branching out from a common root, modelled on similar trees commissioned by the Church to illustrate the descent from Jesse and the House of David to Jesus of Nazareth

. These usually took the form of the image of a tree, branching out from a common root, modelled on similar trees commissioned by the Church to illustrate the descent from Jesse and the House of David to Jesus of Nazareth . Such visual representations of family were designed to create a dynastic identity, legitimising one family's rule, creating a sense of a ruling family that differed from that of their neighbours. All those descended from one single founding individual were thus considered a 'dynasty' or a 'house'. This founder was often a saint. In France, the celebration of descent from Saint-Louis (Louis IX, 1214–1270)[

. Such visual representations of family were designed to create a dynastic identity, legitimising one family's rule, creating a sense of a ruling family that differed from that of their neighbours. All those descended from one single founding individual were thus considered a 'dynasty' or a 'house'. This founder was often a saint. In France, the celebration of descent from Saint-Louis (Louis IX, 1214–1270)[ ], became dominant – the dynasty referred to itself not as 'Capetian' or 'Valois' the way we do now, but as the 'sons of Saint Louis'.20 Other dynasties adopted similar practices: Saint Wenceslas (907–935) in Bohemia, Saint Aleksandr Nevskij (1220–1263) in Russia, Saint Olaf (995–1030) in Norway, and so on. This differed from an earlier, more textual (or even oral) culture, where a royal family was usually defined by living kin, those connected horizontally by blood ties. For example, Charlemagne (747–814), ruler of the Franks, extended his 'family' to include his kin in other Germanic tribes related to him through marriage.21 But these were excluded in later eras; dynasty was now a more vertical association, linking the present to the past.22

], became dominant – the dynasty referred to itself not as 'Capetian' or 'Valois' the way we do now, but as the 'sons of Saint Louis'.20 Other dynasties adopted similar practices: Saint Wenceslas (907–935) in Bohemia, Saint Aleksandr Nevskij (1220–1263) in Russia, Saint Olaf (995–1030) in Norway, and so on. This differed from an earlier, more textual (or even oral) culture, where a royal family was usually defined by living kin, those connected horizontally by blood ties. For example, Charlemagne (747–814), ruler of the Franks, extended his 'family' to include his kin in other Germanic tribes related to him through marriage.21 But these were excluded in later eras; dynasty was now a more vertical association, linking the present to the past.22

These changes in defining who was or was not a member of a ruling family came hand in hand with the development of dynastic rules of succession. Some kingdoms developed systems that allowed for female succession (and thus the adoption of another blood lineage into the royal house) whereas others put in place regulations to prevent this, notably in France with its 'Salic Law' derived from ancient Frankish custom; indeed, most Germanic states adopted this practice as well – resulting, most famously, in the blocking of Queen Victoria of Great Britain (1819–1901) from the succession to her ancestral territories in Hanover in 1837.23

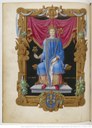

Much of these changes solidified around 1500, when royal dynasties began to make use of new printing technologies to spread propaganda about their dynastic identity, in part, creating historical narratives that connected their present power with an illustrious, sometimes completely fictional past – a descent from one of the sons of Noah, a link to the ancient Trojans, and so on.24 Emperor Maximilian (1459–1519) was an avid proponent of this: having limited genuine power of his own, he 'borrowed' the image of the most ancient dynasty in all of Christendom to lend him its power . Other court families began to publish similar 'genealogical histories' with a similar goal of representing their common identity and legitimising their hold on power and their right to be at court. 'Ancienneté' became more of a basis for access to a monarch at court than merit or even personal favour of the prince.25

. Other court families began to publish similar 'genealogical histories' with a similar goal of representing their common identity and legitimising their hold on power and their right to be at court. 'Ancienneté' became more of a basis for access to a monarch at court than merit or even personal favour of the prince.25

In the 1570s–1580s, royal dynasties all over Europe felt challenged by increasingly powerful aristocratic courtiers. Regulations were therefore put in place to control aristocratic power, and, as pertains to court spaces in particular, to regulate access to the monarch and to elevate certain courtiers above others. Part of this process was to define more clearly who was or was not a member of the royal family: in France, only those who descended from Saint-Louis in the male line were defined as 'princes of the blood' and thus given special privileges and access.26 Other monarchies followed suit. Yet these parameters continued to be challenged by grandees with ever expanding ambitions. In the mid-17th century, therefore, monarchs (in tandem with their diplomats) developed a system of address that made it clearer who was a full member of a major ruling house ('royal highness') as opposed to a secondary power ('serene highness') or merely exalted nobles ('highness'). This system was useful primarily for diplomatic interaction, since it became increasingly desirable to define which dynasties mattered in terms of international relations: the House of Savoy declared itself fully royal in the 1630s, and (gradually) was treated as such ; the House of Lorraine did the same in the 1690s and was mostly ignored, and gradually absorbed by its larger neighbour, France.27 These rankings were mostly settled by the mid-18th century, and published in numerous official manuals to ensure diplomats got it right,28 but they became unsettled again by the Napoleonic Wars and were hammered out again – this time by committee – at the Congress of Vienna in 1815[

; the House of Lorraine did the same in the 1690s and was mostly ignored, and gradually absorbed by its larger neighbour, France.27 These rankings were mostly settled by the mid-18th century, and published in numerous official manuals to ensure diplomats got it right,28 but they became unsettled again by the Napoleonic Wars and were hammered out again – this time by committee – at the Congress of Vienna in 1815[ ].

].

Royal families of the 19th century had to think once more about defining dynasty after this revolutionary period, as monarchy began to be seen as representative of the nation and its people, not as proprietary 'owners' of the state.29 Queen Victoria, for example, had to contend with what to do not just with her own very large clutch of children, but those of her cousins, other offshoots of the House of Hanover. Victoria limited those who could be His/Her Royal Highness (HRH) to children and grandchildren of a monarch, demoting the more distant cousins to HH (His or Her Highness) in official declarations of 1864 and 1898.30 Other royal dynasties followed suit: by the 1880s, the Romanov dynasty in Russia had more than twenty eligible male dynasts. Tsar Alexander III (1845–1894) thus limited the use of the titles 'Imperial Highness' and 'Grand Duke of Russia' to the children and male-line grandchildren, as Victoria had done.31 The Habsburgs in Austria-Hungary had also multiplied, extraordinarily so: towards the end of the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph (1830–1916) there were 30 male heirs, all entitled to the style 'His Imperial and Royal Highness, Archduke of Austria, Prince of Hungary'.32 Both Romanovs and Habsburgs were restricted, however, in a way not limited in Britain: by house rules that demanded equal marriages. Ever since regulations passed in the 1820s and 1830s, a member of these royal houses was required to marry someone from an equally royal house, and lists were carefully drawn up to say who qualified.33

In this we see a very good example of sharing of practice from one dynasty to another. What other practices were shared and how well can we track such cultural exchanges?

The transferral of courtly and dynastic practices to neighbouring courts

One form of cultural exchange that has been studied in detail recently is that accomplished through bride exchanges from one royal court to the next. Clear examples of cultural transfer from court to court can be seen in the patronage networks of Queen Bona Sforza (1494–1557), bringing the Italian Renaissance to Poland-Lithuania in the 1520s–1540s; or Queen Henrietta Maria (1609–1669), the French-born consort in the Stuart court of the 1620s–1640s.34 Under the socio-cultural leadership of consorts like these, court culture in the early modern period began to share many similarities, in behaviour, entertainments and rituals.

One specific set of court rituals that were transferred was the system that regulated how the princely household functioned in day-to-day life – who could approach the sovereign, who had access to the private spaces, how nobles had to behave in the presence of princes, and so on. Historians have referred to this system as the 'Burgundian Protocols'. Originally developed at the court of the dukes of Burgundy in the late 14th century, in part as a means of safeguarding the physical person of the prince, they spread across Europe and developed into a highly sophisticated system delineating which courtiers could get close to the prince, who could stand or sit, who could speak and when, and other details specifying the honours and prerogatives of people attending a prince's court.35 An early example of cultural transfer of these protocols through bride exchange can be seen in Margaret of York (1446–1503) who married the Duke of Burgundy (1433–1477) in 1468; her influence can be seen in the development of the ritual and ceremonial aspects of the court of her brother, Edward IV, king of England (1442–1483).36 A particular feature of the 'Burgundian Protocols' was an increasing distance between prince and courtiers – in contrast to the traditional openness seen at medieval courts, notably in France. This can be seen in the court of Spain, whose kings were also dukes of Burgundy: Emperor Charles V (Carlos I of Spain) (1500–1558) brought the new 'Burgundian Household' to Spain, while his brother and nephews transferred it further afield to the courts of Vienna and Prague.37 Rather ironically, it was not until the 17th century that these protocols 'returned' to France, notably through the influence of two Spanish-born queen-consorts and the imposition of a more 'Burgundian' etiquette, notably the use of the enfilade and the restriction of access to the monarch, which culminated in the 'Versailles system' of Louis XIV.38 This was then reinforced again in the English court through the influence of Henrietta Maria and the fact that her son Charles II (1630–1685) spent so much time at the French court while in exile in the 1650s.39 By the early 18th century a common European court culture, French speaking, had emerged, where courtiers and diplomats could find themselves at home, from Lisbon to St Petersburg.40

Another clear example of transfer occurred when the Bourbon dynasty took over the Spanish throne in 1701 in the person of King Philip V.41 The 'Bourbonisation' of the former Habsburg court was mostly focused on centralisation of the government apparatus, but also included aspects of French ceremonial such as the daily dining in public , and details regulating the dynasty itself, notably the importance of the Salic Law, thus preventing future Spanish infantas from laying claim to the royal succession (through which, of course, the Bourbons had been able to acquire it). The Habsburgs in Austria adopted something similar in 1713, though with the opposite intent, specifically planning for a female succession, and other European courts followed suit in adopting stricter succession regulations – Great Britain of course permitting succession to male or female heirs, but restricting these to Protestants only. By the end of the century, Emperor Paul of Russia (1754–1801), perhaps out of spite for his mother Catherine II (1729–1796)[

, and details regulating the dynasty itself, notably the importance of the Salic Law, thus preventing future Spanish infantas from laying claim to the royal succession (through which, of course, the Bourbons had been able to acquire it). The Habsburgs in Austria adopted something similar in 1713, though with the opposite intent, specifically planning for a female succession, and other European courts followed suit in adopting stricter succession regulations – Great Britain of course permitting succession to male or female heirs, but restricting these to Protestants only. By the end of the century, Emperor Paul of Russia (1754–1801), perhaps out of spite for his mother Catherine II (1729–1796)[ ], significantly altered the Romanov family tradition in formally banning female succession to the throne in 1797.42 These Pauline laws also forbid 'unequal' marriages, adopting a more Germanic practice, as had the Hanoverians in Great Britain with the Royal Marriages Act of 1772 (less specific, but up to the discretion of the sovereign).43

], significantly altered the Romanov family tradition in formally banning female succession to the throne in 1797.42 These Pauline laws also forbid 'unequal' marriages, adopting a more Germanic practice, as had the Hanoverians in Great Britain with the Royal Marriages Act of 1772 (less specific, but up to the discretion of the sovereign).43

Conclusion

Courtly and dynastic culture in the period between 1450 and 1918 witnessed huge changes. These began with changes to the concept of dynasty itself, from a loose kinship association to something more carefully constructed to unify a ruling family. Princely courts were transformed through ritual, from practical places of residence to ceremonial spaces. Key models emerged that were emulated all over Europe, from Burgundy in the 15th century to France in the 18th. The lives of princes and courtiers both were increasingly regulated through codification of practices known as protocols or etiquette. Equally negotiated were the relationships between monarch and courtiers, with senior aristocratic families asserting their positions as holders of the most important court offices. This was accompanied by an elevation of royal status through royal titles and styles such as Royal Highness. Between the 15th and the 19th centuries, a trans-national court culture emerged across Europe, cemented by marriages between royal dynasties and the resulting cultural transfer often effected by royal women.

By the 19th century, in the aftermath of the tumults of the French Revolution, a simpler style of court emerged, following the lead first developed in Berlin and Potsdam respectively in the mid-18th century – a more logical and Enlightened conceptualisation of the court, with its prince as 'first servant of the state' instead of autocratic ruler. It was also significantly cheaper.44 European monarchies were now seen to represent the will of the people, and the people questioned the need for grand ceremonial at court and the number of aristocratic courtiers. 19th-century royal households were reduced in scale and function, notably in Britain, though some huge court cultures remained, such as the court of Russia. Most of these were swept away in the revolutions that followed World War I, though elements of court ceremonial and exaltation of royal dynasties remained in some countries into the modern era.

Jonathan Spangler

Appendix

Online sources

Centre de Recherche du Château de Versailles: Court Identities and the Myth of Versailles in Europe: Perception, Adherence and Rejection (18th–19th centuries), in: Château de Versailles: Centre de Recherche, ongoing since 2017. URL: https://chateauversailles-recherche.fr/english/research/research-programmes/current-research-programmes/court-identities-and-the-myth-of-versailles-in-europe-perception-adherence-and.html [2023-10-06]

Civil List Act 1760, in: vLex United Kingdom. URL: https://vlex.co.uk/vid/civil-list-act-1760-861255254 [2023-10-06]

M. B.: Les Institutions Musicales Versaillaises de Louis XIV à Louis XVI, in: Muse Baroque, published 2014. URL: http://musebaroque.fr/institutions-musicales-versaillaises/ [2023-10-06]

Marrying Cultures: Queens Consort and European Identities 1500–1800. URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20240224032258/http:/www.marryingcultures.eu/ [2024-06-24]

HM Government: Royal Marriages Act 1772, in: National Archives. URL: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/apgb/Geo3/12/11/1991-02-01 [2023-10-06]

Société des Amis de l’Almanach de Gotha: Official Website of the Almanach de Gotha: Online Royal Genealogical Reference Handbook, in: Almanach de Gotha. URL: http://www.almanachdegotha.org/ [2023-10-06]

Spangler, Jonathan: The Rise and Fall of 'Royal Highness': A Brief History of Royal Titles, in: History Extra, published 2019. URL: https://www.historyextra.com/period/stuart/royal-titles-names-history-highness-baby-sussex-harry-explain/ [2023-10-06]

Velde, François: Styles of the Members of the British Royal Family, in: Heraldica, published 2006, last modified January 2022. URL: https://www.heraldica.org/topics/britain/prince_highness.htm [2023-10-06]

Literature

Bizzocchi, Roberto: La culture généalogique dans l'Italie du seizième siècle, in: Annales ESC 4 (July–August 1991), pp. 789–805. URL: https://doi.org/10.3406/ahess.1991.278981 [2023-10-06]

Bucholz, Robert: Going to Court ca. 1700: A Visitor's Guide, in: The Court Historian 5,3 (2000), pp. 181–216. URL: https://doi.org/10.1179/cou.2000.5.3.001 [2023-10-06]

Cauchies, Jean-Marie: Les Ordenanzas de la Casa, Corte y Consejos del archiduque Felipe 'El Hermoso' (1495–1506): en la tradición borgoñona, in: José Eloy Hortal Muñoz et al. (eds.): La Casa de Borgoña: la Casa del rey de España, Leuven 2014, pp. 37–49. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qdz6d.7 [2023-10-06]

Chatenet, Monique: The King's Space: The Etiquette of Interviews at the French Court in the Sixteenth Century, in: Marcello Fantoni et al. (eds.): The Politics of Space: European Courts ca. 1500–1750, Rome 2009, pp. 193–208.

David-Chapy, Aubrée: La 'Cour des Dames' d'Anne de France à Louise de Savoie: un espace de pouvoir à la rencontre de l'éthique et du politique, in: Caroline zum Kolk et al. (eds.): Femmes à la cour de France: Charges et fonctions, XVe–XIXe siècle, Villeneuve-d'Ascq 2018, pp. 49–65.

Dixon, Nicholas: The Evolution of the British Coronation Rite, 1761–1953, in: Anna Kalinowska et al. (eds.): Power and Ceremony in European History: Rituals, Practices and Representative Bodies since the Late Medieval Age, London 2021, pp. 49–65.

Duindam, Jeroen: Dynasties: A Global History of Power, 1300–1800, Cambridge 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107447554 [2023-10-06]

Duindam, Jeroen: Myths of Power: Norbert Elias and the Early Modern European Court, Amsterdam 1995. URN: urn:oclc:record:1359082719 [2023-10-06]

Duindam, Jeroen: Vienna and Versailles: The Courts of Europe's Dynastic Rivals, 1550–1780, Cambridge 2003.

Dumont, Jean: Corps universel diplomatique du droit des gens; contenant un recueil des traitez d'alliance, de paix, de treve, de neutralité, de commerce [...], Amsterdam 1726–1731. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1229594 [2023-10-06]

Elton, Geoffrey: Tudor Government: The Points of Contact: III The Court, in: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 26 (1976), pp. 211–228. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/3679079 [2023-10-06]

Godsey, William D.: 'La Société était au Fond Légitimiste': Émigrés, Aristocracy, and the Court at Vienna, 1789–1848, in: European History Quarterly 35,1 (2005), pp. 63–95. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691405049202 [2023-10-06]

Griffey, Erin: On Display: Henrietta Maria and the Materials of Magnificence at the Stuart Court, New Haven 2016.

Höpel, Thomas: The Versailles Model, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2012-03-22. URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/hoepelt-2010-en, URN: urn:nbn:de:0159-2012030782 [2023-10-06]

Hortal Muñoz, José Eloy: Las Guardas Reales de los Austrias hispanos, Madrid 2013.

Keay, Anna: The Magnificent Monarch: Charles II and the Ceremonies of Power, London 2008.

Kosior, Katarzyna: Becoming A Queen in Early Modern Europe: East and West, Cham 2019 (Queenship and Power). URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11848-8 [2023-10-06]

Kruse, Holger: Die Hofordnungen Herzog Philipps des Guten von Burgund, in: Holger Kruse et al. (eds.): Höfe und Hofordnungen 1200–1600, Sigmaringen 1999, pp. 141–165.

Liddell, Henry George / Scott, Robert: Art. "δυ^ναστ-εία", in: A Greek-English Lexicon (1940). URL: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Ddunastei%2Fa [2023-10-06]

MacGregor, Arthur: The Household out of Doors: The Stuart Court and the Animal Kingdom, in: Eveline Cruickshanks (ed.): The Stuart Courts, Stroud 2000, pp. 86–117.

Mansel, Philip: Dressed to Rule: Royal and Court Costume from Louis XIV to Elizabeth II, New Haven et al. 2005.

Martin, Russell E.: Law, Succession, and the Eighteenth-Century Refounding of the Romanov Dynasty, in: Brian J. Boeck et al. (eds.): Dubitando: Studies in History and Culture in Honor of Donald Ostrowski, Bloomington 2012, pp. 225–242. URL: https://www.russianlegitimist.org/new-page-1 [2023-10-06]

Moeglin, Jean-Marie: Les ancêtres du prince: Propagande politique et naissance d'une histoire nationale en Bavière au Moyen Age (1180–1500), Geneva 1985.

Morgan, David: The House of Policy: The Political Role of the Late Plantagenet Household, 1422–1485, in: David Starkey (ed.): The English Court: From the Wars of the Roses to the Civil War, London 1987, pp. 25–70.

Müller, Frank Lorenz: Stabilizing a 'Great Historic System' in the Nineteenth Century? Royal Heirs and Succession in an Age of Monarchy, in: Frank Lorenz Müller et al. (eds.): Sons and Heirs: Succession and Political Culture in Nineteenth-Century Europe, Basingstoke 2016, pp. 1–https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-45498-0_1 [2023-10-06]

Nassiet, Michel: Parenté, Noblesse et États dynastiques, XVe–XVIe siècles, Paris 2000.

Osborne, Toby: Art. "Diplomatic Ceremonial", in: The Encyclopedia of Diplomacy (2018). URL: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118885154.dipl0409 [2023-10-06]

Osborne, Toby: Language and Sovereignty: The Use of Titles and Savoy's Royal Declaration of 1632, in: Sarah Alyn Stacey (ed.): Political, Religious and Social Conflict in the States of Savoy, 1400–1700, Bern 2014, pp. 15–34.

Paravicini, Werner: The Court of the Dukes of Burgundy: A Model for Europe?, in: Ronald Asch et al. (eds.): Princes, Patronage and the Nobility: The Court at the Beginning of the Modern Age c.1450–1650, Oxford 1991, pp. 69–102.

Persson, Fabian: Survival and Revival in Sweden's Court and Monarchy, 1718–1930, Cham 2020 (Palgrave Studies in Modern Monarchy). URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52647-4 [2023-10-06]

Prosser, Lee: The Princely Houses of Edward, Duke of Kent, in: The Court Historian 23,1 (2018), pp. 40–61. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/14629712.2018.1457497 [2023-10-06]

Raeymaekers, Dries: Access, in: Erin Griffey (ed.): Early Modern Court Culture, London et al. 2022, pp. 125–138. URL: https://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780429277986-11 [2023-10-06]

Reese, M. M.: The Royal Office of the Master of the Horse, London 1976.

Reytier, Daniel: Un service de la Maison du roi: les écuries de Versailles (1682–1789), in: Daniel Roche et al. (eds.): Les écuries royales du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle, Paris 1998, pp. 61–95.

Rouchon, Olivier: Introduction, in: Olivier Rouchon (ed.): L'opération généalogique: cultures et pratiques européennes: XVe–XVIIIe siècle, Rennes 2014. URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.49859 [2023-10-06]

Rowen, Herbert: The King's State: Proprietary Dynasticism in Early Modern Europe, New Brunswick 1980.

Sabatier, Gérard et al. (eds.): ¿Louis XIV espagnol? Madrid et Versailles, images et modèles, Paris 2009.

Sabean, David Warren / Teuscher, Simon: Kinship in Europe: A New Approach to Long Term Development, in: David Warren Sabean et al. (eds.): Kinship in Europe: Approaches to Long-Term Development (1300–1900), New York et al. 2007, pp. 1–32. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1btbw64.5 [2023-10-06]

Schaub, Jean-Frédéric: La France espagnole: Les racines hispaniques de l'absolutisme Français, Paris 2007.

Schock-Werner, Barbara: Art. "Enfilade", in: Wörterbuch der Burgen, Schlösser und Festungen (2004), pp. 115–116.

Silver, Larry: Marketing Maximilian: The Visual Ideology of a Holy Roman Emperor, Princeton 2008. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2fccv0d [2023-10-06]

Spangler, Jonathan: Aulic Spaces Transplanted: The Design and Layout of a Franco-Burgundian Court in a Scottish Palace, in: The Court Historian 14,1 (2009), pp. 49–62. URL: https://doi.org/10.1179/cou.2009.14.1.003 [2023-10-06]

Spangler, Jonathan: Holders of the Keys: The Grand Chamberlain the Grand Equerry and Monopolies of Access at the Early Modern French Court, in: Dries Raeymaekers et al. (eds.): The Key to Power: The Culture of Access in Early Modern Courts, 1400–1700, Leiden 2016, pp. 155–177. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004304246_008 [2023-10-06]

Spangler, Jonathan: Wider Kinship Networks, in: Erin Griffey (ed.): Early Modern Court Culture, London et al. 2022, pp. 57–59. URL: https://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780429277986-5 [2023-10-06]

Spangler, Jonathan: Seeing is Believing: The Ducal House of Lorraine and Visual Display in the Projection of Royal Status, in: Royal Studies Journal 9,2 (2022). URL: https://rsj.winchester.ac.uk/articles/10.21039/rsj.214 [2023-10-06]

Starkey, David: Intimacy and Innovation: The Rise of the Privy chamber, 1485–1547, in: David Starkey (ed.): The English Court: From the Wars of the Roses to the Civil War, London 1987, pp. 71–118.

Stollberg-Rilinger, Barbara: Maria Theresa: The Habsburg Empress in Her Time, Princeton 2021. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2d7x53f [2023-10-06]

Stollberg-Rilinger, Barbara: The Holy Roman Empire: A Short History, Princeton 2018. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc778tr [2023-10-06]

Taylor, Craig: The Salic Law, French Queenship and the Defence of Women in the Late Middle Ages, in: French Historical Studies 29,4 (2006), pp. 543–564. URL: https://doi.org/10.1215/00161071-2006-012 [2023-10-06]

Thurley, Simon: The Politics of Court Space in Early Stuart London, in: Marcello Fantoni et al. (eds.): The Politics of Space: European Courts ca. 1500–1750, Rome 2009, pp. 293–316.

Wortman, Richard: The Representation of Dynasty and 'Fundamental Laws' in the Evolution of Russian Monarchy, in: Richard Wortman (ed.): Russian Monarchy: Representation and Rule, Brighton 2013, pp. 33–73. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781618118547-005 [2023-10-06]

Zwantzig, Zacharias: Theatrum Praecedentiae, oder eines theils illustrer Rang-Streit, Rang-Ordnung, wie nemlich die considerablen Potenzen und Grandes in der Welt nach Qualität ihres Standes, Namens, Dignität und Characters sambt und sonders in der Praecedent, in dem Rang und Tractamente streitig seynd und competiren, Berlin 1706. URN: https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10624330-9 [2023-10-06]

Notes

- ^ Liddell / Scott, Art. "δυ^ναστ-εία" [Dynasty] 1940; see also Duindam, Dynasties 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Persson, Survival and Revival 2020, pp. 1–4.

- ^ This debate was best embodied by Geoffrey Elton and his former student David Starkey when discussing the Tudor court: Elton, Tudor Government 1976; Starkey, Intimacy and Innovation 1987.

- ^ Stollberg-Rilinger, The Holy Roman Empire 2018, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Raeymaekers, Access 2022.

- ^ For an overview of this shift in a trans-regional (or 'trans-aulic') context, see Spangler, Aulic Spaces Transplanted 2009; Schock-Werner, Art. "Enfilade" 2004.

- ^ Chatenet, The King's Space 2009; Bucholz, Going to Court 2000.

- ^ For a comparison, see Duindam, Vienna and Versailles 2003, pp. 21–42.

- ^ For a case study of the Spanish court, Hortal Muñoz, Las Guardas Reales 2013.

- ^ On the important role of the chamberlain in regulating access, see Godsey, 'La Société était au Fond Légitimiste' 2005.

- ^ See for example, the discussion of the 'foreignness' of Somerset House (Denmark House), occupied by Anna of Denmark then Henrietta Maria of France, in Thurley, The Politics of Court Space 2009; David-Chapy, La 'Cour des Dames' 2018.

- ^ Reytier, Un service de la Maison du roi 1998.

- ^ Reese, The Royal Office 1976; MacGregor, The Household out of Doors 2000.

- ^ This division is explored in M. B., Les Institutions Musicales Versaillaises 2014.

- ^ Spangler, Holders of the Keys 2016.

- ^ For a dismantling of the older notion that courtiers were controlled by the etiquette of absolutism, see Duindam, Myths of Power 1995.

- ^ Civil List Act 1760.

- ^ For a case study of the difficulties in surviving under this tighter financial regimen for junior princes in the later 18th century, see Prosser, The Princely Houses 2018.

- ^ Stollberg-Rilinger, Maria Theresa 2021, p. 461.

- ^ Nassiet, Parenté 2000, p. 285.

- ^ See Moeglin, Les ancêtres du prince 1985.

- ^ See a more recent overview, Sabean / Teuscher, Kinship in Europe 2007, especially pp. 4–16.

- ^ Taylor, The Salic Law 2006.

- ^ For fabulous and fictive genealogies, see Bizzocchi, La culture généalogique 1991.

- ^ Rouchon, Introduction 2014; Silver, Marketing Maximilian 2008.

- ^ Spangler, Wider Kinship Networks 2022, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Osborne, Art. "Diplomatic Ceremonial" 2018; Osborne, Language and Sovereignty 2014; Spangler, Seeing is Believing 2022.

- ^ For example, Dumont, Corps universel diplomatique 1726–31; or Zwantzig, Theatrum Praecedentiae 1706.

- ^ Rowen, The King's State 1980.

- ^ Velde, Styles 2022.

- ^ Wortman, The Representation of Dynasty 2013.

- ^ Spangler, The Rise and Fall of 'Royal Highness' 2019; for a detailed look at this issue, see Velde, Styles 2022; see also Müller, Stabilizing a 'Great Historic System' 2016.

- ^ Regulated by the Almanach de Gotha, published since the 18th century and recently revived; rivalled by the online only Société des Amis de l’Almanach de Gotha, Official Website of the Almanach de Gotha.

- ^ Both women featured in the Humanities in the European Research Area project, Marrying Cultures 2016. Recent studies include, for Bona Sforza: Kosior, Becoming A Queen 2019; for Henrietta Maria: Griffey, On Display 2016.

- ^ See Paravicini, The Court 1991; Kruse, Die Hofordnungen 1999; Spangler, Aulic Spaces Transplanted 2009, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Morgan, The House of Policy 1987.

- ^ See Cauchies, Les Ordenanzas de la Casa 2014.

- ^ See Sabatier, ¿Louis XIV espagnol? 2009; Schaub, La France espagnole 2007.

- ^ Keay, The Magnificent Monarch 2008, pp. 171–182.

- ^ The extent of this common culture being labelled as the 'Versailles System' was the subject of a major research project, Court Identities and the Myth of Versailles in Europe 2017.

- ^ See Höpel, The Versailles Model 2012, paragraph 32.

- ^ Martin, Law 2012.

- ^ HM Government, Royal Marriages Act 1772.

- ^ This shift is explored chiefly by looking at court dress, by Mansel, Dressed to Rule 2005, notably in chapters 2 ("Service") and 4 ("Revolutions").