Introduction

While historians have rightly described the brief Dominus ac Redemptor of July 1773 as a major event in church history, it came as no surprise to most of Europe's contemporary newspaper readers and had in fact been long anticipated with either foreboding or delight, depending on the reader's perspective.1 Indeed the issuing of the papal brief was treated as an event of minor importance by the contemporary media, particularly when compared with the frenzy of fifteen years earlier when the first news of the expulsion of the Jesuits from Portugal spread all over Europe and led to journal articles, new and specialized periodicals, satirical engravings, prints and pamphlets, compilations of documents and multi-volume tracts. When Portugal's minister Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (1699–1782), Marquês de Pombal, began his assault on the most powerful Christian religious order in 1759, the echo was heard all over Europe, both in Catholic and Protestant states. This momentous event prompted journalists, authors and translators, engravers, anthologists and editors to comment on the affair, thus fuelling a transnational debate that soon turned into a battle of fundamental ideas about state, society and religion. Engaging a larger informed public in the recipients of the 'latest news', this debate provides evidence for the formation of a European public sphere transcending the social frontiers of the Republic of Letters and the salons. Moreover, the debate demonstrates how in early modern Europe a major media event could serve as an important catalyst for the transfer of ideas and discourses.2 The polarization of the public sphere during the age of enlightenment and the reciprocal condemnation of adversarial groups like philosophes, Jansenists, and Jesuits may therefore be regarded to some degree as the result of transfer processes initiated by transnational media events.

Like the suppression itself, the media event unfolded in several stages, each of which had its own characteristics and transnational dynamics. It began with a piece of news that, on the face of it, had no connection with the Society of Jesus: In January 1759 the Portuguese court announced that King Joseph I (1714–1777) had been the target of an assassination attempt in September 1758, a fact that had been kept silent for some months by the Portuguese government. Occurring only months after the attempted assassination of the French King Louis XV (1710–1774) in January 1757, the news of the attempted regicide shocked the European public.3 Rumours soon began to circulate, however, suggesting that the Jesuits had had some part in this affair. The consensus of opinion which had initially characterized the response of the press throughout Europe vanished immediately and the news item of the attempt on the life of the Portuguese king turned into a controversy about the Jesuits. The king and his minister Marquis of Pombal expelled the Jesuits from Portugal in September 1759, accusing them of having provided a theological justification for, and having actually instigated, a plot against the king's life in order to cover up their rebellion in South America, where they had allegedly seized royal territory and founded an independent 'Jesuit Republic'.4 This first stage of the media event lasted until 1761, when a controversy involving finances and a Jesuit missionary in the French Caribbean called Father Lavalette caused public attention to shift from Portugal to France. Inspired by the Portuguese example, the French high courts or parlements used the Lavalette affair to launch an attack on the French branch of the order, eventually denouncing Father Lavalette's doctrines as seditious. In 1761/1762, much to the king's displeasure, the magistrates declared the constitutions of the order incompatible with the laws and customs of the realm, closed down the Jesuit colleges and forced the fathers to renounce their religious vows or leave the kingdom. Louis XV, seeing no means of contravening the actions of the parlements, confirmed the interdiction in 1764.5 The Society of Jesus had then lost two of its most important branches and the cumulative character of the repressive acts against the Jesuits was obvious to contemporary newspaper readers. The third and last stage of the media event began with the expulsion of the fathers from Spain and its colonies in 1766.6 It was then generally believed that the fate of the Society of Jesus as a whole was at stake, a perception which was reinforced by the Jesuits' banishment from Naples in 1767 and from Parma in 1768, and was confirmed by Pope Clement XIV's (1705-1774) issuing of the brief Dominus ac Redemptor in 1773.

Stage one: Pombal's campaign and the anti-Jesuit network

The first stage of the media event was marked by the impressive press campaign orchestrated by the Marquis of Pombal. In order to justify his severe treatment of the fathers, the minister arranged for the dissemination of all official documents issued by the crown concerning the Jesuits. Among these documents was the judgment of the special tribunal appointed to investigate the assassination attempt. Though it did not deal directly with the Jesuits, it strongly condemned the Jesuit fathers Malagrida, Matos and Alexander.7 Other notable documents included a tract denouncing the immoral and seditious doctrine of tyrannicide which implied that members of the order had been teaching this doctrine to the king's subjects,8 the royal edict of September 1759 accusing all Portuguese Jesuits collectively of high treason and ordering their banishment,9 and the verdict pronounced in 1761 by the Portuguese Inquisition against the Jesuit Father Gabriele Malagrida (1689–1761) who was convicted of heresy and condemned to be burned in an auto-da-fé.10

As soon as these official documents were published, innumerable reprints, translations and compilations were produced all over Europe.11 Newspaper editors filled issue after issue with continuing accounts of the Portuguese affair and with extracts from the royal documents. Engravers produced visual representations of the anti-Jesuit stereotypes which had been employed by the Portuguese ministry to support its accusations against the Society of Jesus. Anonymous authors in France, Italy, the Netherlands and Germany discussed the matter in pamphlets and argued either in favour of, or against, the society. New historical tracts attempted to provide further evidence against the order, or conversely to justify its operations in the Portuguese colonies. The media event reached its first climax only a few months after the first news of the assassination attempt.

The considerable success throughout Europe of the Portuguese government's campaign to discredit the Jesuits has long been attributed to the deliberate actions of Pombal. Yet this is to considerably overestimate the minister's actual influence on the European public sphere. Even in the age of royal absolutism, the transnational press – in contrast to the national press – was not easily controlled, especially when religious or confessional issues were at stake. Pombal did indeed give decisive impulses to the European debate by arranging for the documents to be widely circulated and translated into French. But the sheer enormity of the European debate on the Portuguese Jesuits cannot be attributed to his genius alone. Two facts were equally decisive: firstly, the special quality of the Portuguese accusations against the Jesuits; and secondly, the existence of an anti-Jesuit network spanning France, Italy and the Netherlands.

It is clear that Pombal relied heavily on pre-existing negative stereotypes of the Jesuits to justify his measures against the order and that he actually borrowed from well-known anti-Jesuit pamphlets in formulating his accusations. In the official publications, he pointed to the lax morals of the fathers, their tyrannicidal and seditious teachings, their craving for power, their dubious internal organization and the conspiratorial nature of the order.12 Thus what secured the success of his press campaign was less its originality than the fact that these serious accusations now bore the stamp of royal authority. This manifested itself particularly clearly in the writings of the German translator and editor of Pombal's documents, Anton Ernst Klausing (1739–1803). Discussing the veracity of accusations against the Jesuits, he argued that "all writings published against the Jesuits on behalf of public authorities after a proper judicial examination are unquestionable testimony and definite evidence of the truth of the allegations contained therein."13 Klausing ventured into philosophy to support his argument. In the domain of human actions truth cannot be established beyond doubt by logical deduction. Truth must therefore be established by more pragmatic means, Klausing argued. The stability of a state or society depends on the acceptance of official statements by the general public. If this acceptance did not exist, the whole social order would be in peril and would collapse sooner or later.14 Ultimately, then, the acceptance of the Portuguese accusations as true was a political and social – as well as an epistemological – necessity.

Though few contemporaries went to the same lengths as Anton Klausing, a German Protestant, to justify their anti-Jesuit invective, the official character of the Portuguese documents nonetheless lent considerable weight to their arguments. Challenging the Portuguese accusations against the Jesuits was tantamount to offending the Most Faithful King Joseph I. The Jesuits' enemies never ceased pointing out that the order's defenders were in effect as guilty of lèse-majesté as the would-be regicides. This constituted a substantial difficulty for the Jesuits' supporters and may partly explain the massive preponderance of anti-Jesuit voices in the transnational debate.

Another factor fuelling the media event and helping to spread it across Europe in this first phase was the contribution of groups other than the Portuguese government. The Jesuits had traditional enemies who jumped at the opportunity to discredit the order and eagerly produced translations of the Portuguese documents, as well as complementary publications. Most notable among these enemies were the Jansenists, who were persecuted as heretics in France but managed to maintain an extraordinary degree of organization in the Parisian underground. They also had close connections to like-minded Catholics in Italy and the Netherlands.15

The parti janséniste, as they were already referred to by contemporaries, were expert in underground publishing and possessed several secret printing presses and a well-organized distribution network in Paris.16 Ever since they began their campaign against the bull Unigenitus (1713) reiterating papal condemnation of Jansenism, they had been producing countless pamphlets and engravings denouncing the persecution of the "saints" and the harassment they had to endure by ecclesiastical and lay authorities and, in particular, the Jesuits. The centrepiece of their publicity campaign, however, was the Nouvelles ecclésiastiques, ou Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de la constitution Unigenitus , a clandestine weekly which ardently defended the Jansenist cause from 1728 to 1803. It is estimated that it had an average print run of 2,000 copies, rising at times to an extraordinary 6,000 copies. It was read not only in France, but also in Italy, Germany and the Netherlands, where it was reprinted.

, a clandestine weekly which ardently defended the Jansenist cause from 1728 to 1803. It is estimated that it had an average print run of 2,000 copies, rising at times to an extraordinary 6,000 copies. It was read not only in France, but also in Italy, Germany and the Netherlands, where it was reprinted.

Some of the most eminent figures of the parti janséniste engaged in the wider dissemination of the Portuguese documents and also made their own contributions to the public debate. For instance, most of the Portuguese documents were translated into French by Pierre-Olivier Pinault (died 1790), a Parisian barrister who was known to be a fervent devotee of the Jansenist saint François de Pâris. From January 1759 to June 1761, another member of the Jansenist group, former Dominican Jean-Pierre Viou (1707–1781), edited a new periodical which focused on the Portuguese affair, in which he could rage anonymously but all the more ferociously against the Jesuits. His Nouvelles intéressantes, au sujet de l'attentat commis … sur la personne sacrée … le roi de Portugal were widely distributed, reprinted several times and translated into Italian and German.17 At the same time a number of anti-Jesuit pamphlets and compilations were also edited and re-edited in the Jansenist underground. Another speciality of the French Jansenists was the mass production of satirical engravings. These were so widespread that they can still be found today not only in French, but also in Portuguese, Italian and German collections. Finally, the Nouvelles ecclésiastiques reported weekly on the Portuguese controversy, reviewed the contributions of the most important publications and represented the affair visually in its annual frontispieces.

A group of reformist Catholics in Italy known as the cercolo dell'Archetto maintained frequent correspondence with the Parisian Jansenists and played a similar role in the course of the media event as the latter.18 The Italian reformists published some of the most influential anti-Jesuit tracts and brought the transnational debate to Italy. Their Riflessioni di un Portoghese and their Appendice alle Riflessioni sought to add historical evidence to the Portuguese accusations, arguing that the Jesuits had at all times offended ecclesiastical and lay authorities, and maintaining that the main objective of the order was the expansion of its own power in order to achieve global domination.19 The publications of the Archetto were particularly famous and provoked numerous publications countering or supporting their arguments. They were translated not only into French and German, but also into Portuguese, English and Spanish.

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the first Jesuit to take it upon himself to respond anonymously to the accusations against his order was an Italian. Francesco Antonio Zaccaria (1714–1795), who had already attained some notoriety in the Republic of Letters with his Storia letteraria d'Italia, began a long series of replies to the Portuguese accusations, in which he adopted the paranoid style of his many adversaries, denouncing a conspiracy of Jansenists, enlightened philosophers and unbelievers against the Christian faith and the church.20 His arguments received the support of other anonymous defenders of the order in France and Italy, but all in all the supporters of the Jesuits were far outnumbered by their opponents.

It was primarily as a result of debate in Italy that the transnational controversy reached the Holy Roman Empire. In contrast to the media event as it unfolded in Portugal, France and Italy, in Germany the Jesuits' defenders and detractors were more evenly matched. While the anti-Jesuit camp consisted mainly of Protestants like Klausing, the Jesuits of Augsburg were quick to translate nearly all pro-Jesuit writings that had appeared in France and Italy.21 Also, unlike the other languages discussed so far, at this stage there were comparatively few important original contributions to the debate in German. Instead documents disseminated in Portugal, France and Italy were simply translated into German.

Hence the first stage of the media event was characterized by Pombal's press campaign and the activity of the Jansenist network, while the Jesuits and their supporters were forced into the defensive. Needless to say, it was virtually impossible to publish any pro-Jesuit comments in Pombal's Portugal and it was certainly difficult to do so in France with the parlements monitoring the press market. But the difficulties faced by Jesuit supporters went beyond this, as a closer examination of the newspapers shows. Whereas articles on the attempted regicide in Portugal were published in Protestant and Catholic newspapers alike, a distinct divide between the confessions developed as the media event became more of a controversy about the Jesuits. Protestant papers like the very influential Hamburgischer Unpartheyischer Correspondent or the French-language Dutch journals immediately seized on the Portuguese controversy and for several months filled their issues with the latest news from Lisbon. Catholic papers like the Courrier d'Avignon or the Augsburger Postzeitung, however, soon hushed up the affair. The Catholic publicists in Augsburg did publish some of the Portuguese documents, but eliminated every trace of the Jesuits in them, thereby making them virtually incomprehensible. Eventually, most of the Catholic press decided not to contribute to the media event and began pretending that nothing had happened at all. The Augsburger Postzeitung, for example, did not inform its readers at all of the expulsion of the order from Portugal or the interdiction in France.

Preliminary bibliographical research indicates that throughout the whole period under study here the number of publications about the Jesuits in languages such as English, Latin, Dutch, Spanish or Polish was not significant.22 This does not mean that the debate did not reach these countries, but rather that it was received through the lingua franca of the time, i.e., French. Our understanding of the media event could usefully be expanded by the consideration of, for example, differing attitudes in the periodical presses of Poland and England. In the absence of comprehensive studies of local newspapers during the Jesuit affair, however, our knowledge of how the media event unfolded in Eastern and Northern Europe remains at best incomplete. It would appear that hardly any original contributions to the debate emanated from these regions – with the notable exception of the Netherlands, where Huguenot and Jansenist refugees published pamphlets and press articles, albeit in French.

Stages two and three: From controversy to consensus

As in the case of the first stage of the media event, the second stage was largely defined by official documents which were distributed widely. By 1761/1762, the importance of the Portuguese documents declined and they were gradually superseded by the printed decisions and decrees made against the Jesuits by the French parlements , notably by the Parisian parlement. All decrees of the parlements were, of course, published as a matter of course. But in the case of the anti-Jesuit legislation, the print runs by far exceeded the ordinary. Also, in geographical terms the circulation of the documents was not limited to the parlements' respective districts as was usually the case. Publication in broadsheets as well as translation into Italian, German and Portuguese guaranteed the Europe-wide reception of the texts. Moreover, the Nouvelles ecclésiastiques, the French-language Dutch newspapers, the Hamburgischer Unpartheyischer Correspondent and many other European journals printed large extracts of the decrees, while most of the Catholic press remained silent of the Jesuit affair.

, notably by the Parisian parlement. All decrees of the parlements were, of course, published as a matter of course. But in the case of the anti-Jesuit legislation, the print runs by far exceeded the ordinary. Also, in geographical terms the circulation of the documents was not limited to the parlements' respective districts as was usually the case. Publication in broadsheets as well as translation into Italian, German and Portuguese guaranteed the Europe-wide reception of the texts. Moreover, the Nouvelles ecclésiastiques, the French-language Dutch newspapers, the Hamburgischer Unpartheyischer Correspondent and many other European journals printed large extracts of the decrees, while most of the Catholic press remained silent of the Jesuit affair.

The Jansenist network – already active during the first phase of the media event – certainly intensified its editorial activities in the wake of the Lavalette affair and the interdictions. This time, however, the parti janséniste did not restrict its activities to the publishing arena alone. Members of the party were among the magistrates and formed a particularly active minority within the Parisian parlement. In fact, it was on the initiative of the Jansenist magistrate Abbé Germain Louis de Chauvelin (1685–1762) that the parlement of Paris resolved to examine the doctrine and the constitutions of the Jesuits in the first place.23 Close cooperation between this minority in the parlement and eminent Jansenist publicists like Louis-Adrien Le Paige (1712–1802) had already occurred during the "refusal of sacraments" controversy of the 1750s, when the parlement's remonstrations to the king had virtually been composed by a group of Jansenist barristers.24 This cooperation resumed when the fate of the Jesuits was decided. The arguments propounded in the parlement and published for a European public heavily relied on an important and voluminous historical tract composed by Le Paige and his fellow Jansenist Christophe Coudrette (1701–1774).25 Thus, the parti janséniste even managed to insert its arguments into the official documents published on behalf of the parlements.

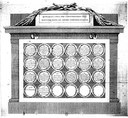

As already mentioned, the Jansenists did not rely on the parlement's publications alone to persuade the public of the Jesuits' harmfulness. Apart from various anti-Jesuit pamphlets, the mass production of engravings was another striking Jansenist contribution to the media event. A Jansenist artist with the pseudonym of Montalais produced at least 20 anti-Jesuit engravings which were used as broadsheets, book illustrations or frontispieces. Many images presented a particular accusation or stereotype, such as the Jesuit's trading business, their moral corruption or their lust for power. Some images were in fact reprints of Jesuit originals that were now presented as evidence of the order's arrogance and excessive pride. Montalais and Nicolas Godonnesche (died 1761), another quite productive Jansenist artist, both had a particular preference for medal engravings imitating the famous Histoires métalliques glorifying the reign of Louis XIV (1638–1715).26

Many images presented a particular accusation or stereotype, such as the Jesuit's trading business, their moral corruption or their lust for power. Some images were in fact reprints of Jesuit originals that were now presented as evidence of the order's arrogance and excessive pride. Montalais and Nicolas Godonnesche (died 1761), another quite productive Jansenist artist, both had a particular preference for medal engravings imitating the famous Histoires métalliques glorifying the reign of Louis XIV (1638–1715).26

These mostly allegorical images depicted the parlements as the incarnation of Justice and as protectors of the French nation, whereas depictions of the Jesuits employed typical stereotypes: the poisoned chalice representing the profanation of the sacred sacraments or murder, the dagger corresponding to conspiracy and regicide, and the mask standing for their constant dissembling.

After the first decisive decree of the parlement of August 6th 1761, the French Jesuits, who had not commented on the Portuguese affair up to then, began to respond to attacks and finally engaged in the public debate. For the most part, their rebuttals were constructed as responses to a single anti-Jesuit pamphlet or to an official document, which they attempted to refute point by point in a quite scholastic manner. Many French Jesuits responded to the accusations with the knowledge and consent of their superiors, but on condition that they show due respect to the parlement.27 Others, however, like Theodore Lombard (1699/1708–ca. 1770) from Toulouse or André Christophe Balbany from Marseilles, acted more independently and their compositions took on the aggressive style of the pamphlet debate.28 In general, however, the Jesuits were considerably constrained in their attempts to defend the order, as General Lorenzo Ricci (1703–1775) in Rome had forbidden his French confreres to comment on the awkward question of Gallicanism at all. His fear was that the order might lose the support of the French episcopacy if, while defending itself, it spoke in favour of papal supremacy. Yet most of the Gallican bishops were determined to defend the order, and readily did so in pastoral letters that were printed and disseminated far beyond their respective dioceses, only to be proscribed by the parlements.29 Latterly, as the decrees of the parlements were applied and the Jesuits' colleges and residences were confiscated, growing material difficulties made publicist activity more and more difficult.

or to an official document, which they attempted to refute point by point in a quite scholastic manner. Many French Jesuits responded to the accusations with the knowledge and consent of their superiors, but on condition that they show due respect to the parlement.27 Others, however, like Theodore Lombard (1699/1708–ca. 1770) from Toulouse or André Christophe Balbany from Marseilles, acted more independently and their compositions took on the aggressive style of the pamphlet debate.28 In general, however, the Jesuits were considerably constrained in their attempts to defend the order, as General Lorenzo Ricci (1703–1775) in Rome had forbidden his French confreres to comment on the awkward question of Gallicanism at all. His fear was that the order might lose the support of the French episcopacy if, while defending itself, it spoke in favour of papal supremacy. Yet most of the Gallican bishops were determined to defend the order, and readily did so in pastoral letters that were printed and disseminated far beyond their respective dioceses, only to be proscribed by the parlements.29 Latterly, as the decrees of the parlements were applied and the Jesuits' colleges and residences were confiscated, growing material difficulties made publicist activity more and more difficult.

From the very beginning of the media event, there was a third party which had contributed occasionally to the debate without supporting either the Jesuits or Jansenists. Detached from, and indifferent to, the religious controversy, Voltaire (1694–1778) had commented ironically on the affair of the Portuguese Jesuits.30 He incorporated some of Pombal's stereotypical arguments in his famous Candide, which first appeared in print in 1759. In spite of his general hostility towards the order, Voltaire nonetheless vehemently disapproved of the treatment of the eighty-year-old Gabriele Malagrida, who was burned during an auto-da-fé in 1761. Throughout the French affair, Voltaire and his fellow philosophes were somewhat torn between their hatred of the Jesuits and their contempt for the now victorious Jansenists. In the aftermath of the royal recognition of the parlements' anti-Jesuit legislation in 1764, Jean le Rond d'Alembert (1717–1783) published a pamphlet declaring that, by forbidding the Society of Jesus, the magistrates had in fact acted under the influence of an increasingly prevalent esprit philosophique among the French public. At the same time, he stated that the Jansenists were doomed, as their raison d'être had vanished along with the Jesuits.31 The most heated responses to d'Alembert's revision of events in favour of the philosophes predictably came from the Jansenists, who felt cheated out of the credit for bringing down the Jesuits in France. From this point, the parti janséniste increasingly shifted the focus of their polemical compositions from their traditional Jesuit opponents to those other enemies of faith and church, the enlightened philosophers.

While the public debate reached a peak in France in 1761 and 1762 and was sustained by the d'Alembert controversy in 1765, its transnational impact slightly decreased. The decisive decrees of parlements were, of course, distributed abroad and the news of the French Jesuits' fate spread throughout Europe. The most important anti-Jesuit tracts continued to be translated into Italian. But Anton Ernst Klausing did not follow through on his undertaking to translate and publish the main French documents. The influential Histoire générale by Christophe Coudrette and Louis-Adrien Le Paige was translated into German only in 1785 in the context of the enlightenment-versus-obscurantism debate.32 However, as all educated readers in Europe were able to read French, the number of translations might not – in contrast to the Portuguese controversy – be a dependable indicator of the transnational impact of the debate. Moreover, the volume of original French-language documents contained in German libraries today indicates that the most important documents were read in Germany in the original. It seems equally fair to assume, however, that the juridical intricacies of the affair did not interest the broader public outside France. As regards the accusations levelled against the order, nothing much new was added to those already published by Pombal, in marked contrast to the pro-Jesuit side of the debate. The Jesuits of Augsburg translated virtually all French apologies and published a multi-volume edition in defence of their order. The volume of pro-Jesuit writings was thus disproportionately higher in Germany. In almost all other Catholic states in Western Europe at that time, however, the order's opportunities to defend itself were severely constrained and it had to cope with Jesuit refugees from Portugal and, subsequently, from Spain and its colonies also. Potential supporters of the order such as the French episcopacy were silenced by the authorities.

The decline of the transnational debate about the Jesuits became even more apparent during the final stage of the media event after 1765. The papal bull Apostolicum pascendi issued in January 1765, while intended as a clear signal of support, was rejected by all important Catholic powers including Austria and served instead as grist to the mill of the anti-Jesuit lobby. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain, the Spanish crown attempted in 1767 to imitate Portugal and published official records concerning the Jesuits.33 While these documents were translated into French, Italian and German, and printed by several newspapers, they did not provoke a response in any way comparable to the publicist activity witnessed in 1759 or 1761. This may be explained by the fact that, unlike the Portuguese and French documents, the only evidence furnished in the Spanish documents were the king's own assertions. Indeed Charles III (1716–1788) even declared that the exact reasons for the condemnation of the Jesuits were a matter for him and not for public disclosure. The order banning the Jesuits even forbade any public debate on the matter on pain of death. While this did not, of course, apply to anyone outside Spain, it did nothing to encourage discussion of events.

issued in January 1765, while intended as a clear signal of support, was rejected by all important Catholic powers including Austria and served instead as grist to the mill of the anti-Jesuit lobby. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain, the Spanish crown attempted in 1767 to imitate Portugal and published official records concerning the Jesuits.33 While these documents were translated into French, Italian and German, and printed by several newspapers, they did not provoke a response in any way comparable to the publicist activity witnessed in 1759 or 1761. This may be explained by the fact that, unlike the Portuguese and French documents, the only evidence furnished in the Spanish documents were the king's own assertions. Indeed Charles III (1716–1788) even declared that the exact reasons for the condemnation of the Jesuits were a matter for him and not for public disclosure. The order banning the Jesuits even forbade any public debate on the matter on pain of death. While this did not, of course, apply to anyone outside Spain, it did nothing to encourage discussion of events.

After the banishment of the Jesuits from Spain, the total suppression of the order was widely expected, and corresponding rumours appeared every now and then in the European press. When the papal suppression eventually occurred in the summer of 1773, it elicited a predictable response throughout Europe. Numerous editions and translations of the papal brief were distributed and commented on; engravings celebrated the victory of the united Catholic powers over the Jesuit hydra.34 However, as there was almost nobody left to support the Jesuits, no real controversy developed from this. The media event had turned from controversy to consensus. The only critical voices were heard in Germany, where the Jesuits survived in places or were at least allowed to continue their usual activities for several years.

The content of the transfer process: From history to conspiracy theory

The purpose of Pombal's campaign was to gain Europe-wide acceptance for the official Portuguese version of the Jesuit affair in order to justify the expulsion of the fathers. According to this version, Jesuit missionaries had usurped Portuguese territory in Paraguay in order to establish an independent "Jesuit Republic" and to enslave the native Guaraní, their primary goal being the enrichment of their order. As the king was about to discover their betrayal, the Jesuits plotted to murder him. To this end, they conspired with a group of discontented noblemen and abused their spiritual authority by assuring the noblemen in the confessional that the murder of King Joseph I only constituted a venial sin.

While this official Portuguese version purported to deal only with concrete "facts", the broader transnational debate sought to identify the fundamental causes of the affair. Most of the anti-Jesuit publications tried to reinforce the Portuguese accusations with the addition of historical evidence. As the Jansenists played a central role in this communication process, the view of history propounded in the course of the media event corresponded to their particular version of the past. "On peut dire avec vérité que depuis deux cents ans il s'instruit contre les Jésuites, à la face de tout l'Univers, un Procès criminel & de Religion & d'Etat", wrote Jansenist Charles Clémencet (1703–1778) in 1759.35 In most of the Jansenist publications, the Portuguese affair was explained in the context of the theological controversy which since the mid-seventeenth century had pitted Jesuits against Jansenists, or "defenders of the true faith" as the latter preferred to call themselves. Moral laxism, Molinism (or probabilism) and Pelagianism were only some of the keywords of this debate. The most concise version of this ubiquitous Jansenist historical narrative appeared in the Nouvelles ecclésiastiques. At the beginning of his review of a Portuguese document, the Jansenist journalist outlines the general historical background of the present affair as follows:

Depuis plus de 100 ans deux Corps d'hommes, les Jésuites d'un côté, les Défenseurs de la doctrine de Saint Augustin de l'autre, donnent à l'Eglise le spectacle singulier de s'accuser mutuellement. … Après plus d'un siècle de calomnies de la part des Jésuites, … l'Eglise n'en est que plus convaincue de la fausseté de ces calomnies. La Doctrine & la Morale des prétendus Jansénistes sont reconnues de toute part pour saines & orthodoxes.36

He then seamlessly incorporates the Portuguese narrative of the Jesuit "Republic of Paraguay" into the broader Jansenist historical narrative:

On les a dénoncés à l'Eglise comme coupables d'une Morale dépravée, même impie, d'une doctrine pestiférée, meurtrière, autant contraire au repos des Sujets, qu'à la sûreté des Rois. … On les a accusés de renverser la doctrine de l'Evangile, & d'y substituer un Corps de dogmes erronés. … Enfin, sans insister sur tant d'autres excès, on les accuse, depuis cent ans, d'abuser du prétexte de la propagation de l'Evangile, pour satisfaire dans les Indes, & singulièrement dans le Paraguay, leur avarice insatiable; pour s'emparer des richesses de cette excellente portion des Indes occidentales; pour y réduire les Indiens à une odieuse servitude; … en un mot pour y établir une sorte de République Souveraine ….37

The Jansenist understanding of recent history was strongly influenced by their figurist theology, which assumed that everything that happened was prefigured in the narrative of the Bible. Focussing especially on St. Paul's Epistle to the Romans, the Jansenists based their perception of themselves as persecuted witnesses of the truth in a time of trouble on their prophetic reading of the Bible.38 This resulted in a rather Manichean vision of history, where the witnesses of the truth had constantly to defend themselves against the forces of evil. Applied to their current situation, the role allocation was clear: while the Jansenists fought for the true faith, the Jesuits were the spearhead of evil. This Jansenist interpretation was not only propounded by many contemporary books and pamphlets, but also depicted in visual form in various engravings produced during the media event. Published around 1762, the anonymous etching La prière charitable is divided into a dark left side and an enlightened right one. On the left, a fig tree bears the portraits of famous Jesuits as fruit and is crowned by a demon. Among the Jesuits appear such prominent figures as the fathers Molina and Escobar, famous among Jansenists for their highly controversial moral teachings. An avenging angel strikes them with bolts of lightning. On the right side, an assembly of clergymen is illuminated by divine light. The accompanying text cautions against the bitter fruit of the fig tree and at the same time begs God's mercy for the misguided. From the Jansenists' point of view then, the whole Jesuit controversy ultimately derived its meaning from the history of salvation.

is divided into a dark left side and an enlightened right one. On the left, a fig tree bears the portraits of famous Jesuits as fruit and is crowned by a demon. Among the Jesuits appear such prominent figures as the fathers Molina and Escobar, famous among Jansenists for their highly controversial moral teachings. An avenging angel strikes them with bolts of lightning. On the right side, an assembly of clergymen is illuminated by divine light. The accompanying text cautions against the bitter fruit of the fig tree and at the same time begs God's mercy for the misguided. From the Jansenists' point of view then, the whole Jesuit controversy ultimately derived its meaning from the history of salvation.

Yet salvation history was not the only way to interpret events. Other more secular historical narratives also provided material with which to attack the Society of Jesus. In accusing the Jesuits of teaching the doctrine of tyrannicide to the Portuguese people, Pombal was playing on an old theme. The memory of the Wars of Religion with their numerous assassinations of kings and other dignitaries had been revived by the recent attempted regicides in France and Portugal. The memory of the two assassination attempts against King Henry IV (1553–1610) placed the Jesuits in a particularly invidious position in France, from which the order had already been expelled in 1595 in the aftermath of the two attempts on the king's life. The assassins Pierre Barrière (died 1593) and Jean Chastel (1575–1594) were both associated in some way with the Jesuits, the former denouncing the head of the Parisian Jesuit college Claude de Varade, the latter being a former student at that same college. In January 1595, the Jesuit fathers left France after the execution of one of their confreres, Father Guignard, who had been accused of complicity with Chastel. A pyramid-shaped monument was erected near the Palais de Justice to commemorate the Jesuits' supposed attempted regicide, though it was removed only a few years later when Henry IV invited the Society of Jesus to return to France.

was erected near the Palais de Justice to commemorate the Jesuits' supposed attempted regicide, though it was removed only a few years later when Henry IV invited the Society of Jesus to return to France.

This Jesuit controversy of the late-sixteenth century produced some famous and enduring anti-Jesuit pamphlets, among them the pleas of Etienne Pasquier (1529–1615) and Antoine Arnauld (1612–1694), father of the famous Jansenist. During the Jesuit affair of the 1760s, both texts were cited liberally and also fundamentally re-edited.39 A number of engravings also revived the memory of the demolished anti-Jesuit monument of 1595. However, the debate did not only rely on such ancient texts, but also produced new "evidence". In 1758, a tract entitled Les Jésuites criminels de lèze-majesté dans la théorie et dans la pratique became a major source of inspiration to most of the anti-Jesuit authors.40 The first part of the book was a compilation of quotes from Jesuit writings on the issues of tyrannicide and papal supremacy. The anonymous author eventually came to the conclusion that:

Un des points fondamentaux de leur doctrine est que le Souverain Pontife a une pleine puissance de jurisdiction qui s'étend sur tous les Princes de la terre, qu'il peut à son gré déposer les Rois, les priver de leurs Etats, annuller leurs loix, & précéder contre eux non seulement par voie de censures, mais encore par des peines extérieures, & en employant la violence & les armes. … Ainsi dans ce systême le Pape est un Monarque universel à qui tous les Souverains sont assujettis.41

As regards the issue of tyrannicide, this "ultramontane" doctrine implied that "[p]our faire du Prince légitime un usurpateur, il suffit qu'il ait été déposé par le Pape, & qu'il refuse de se soumettre au jugement qui prononce cette disposition."42 Thus condemned as a usurper, the prince could then legitimately be killed. The second part of the book purported to illustrate the practical application of this doctrine throughout history. It traced a chain of assassination attempts supposedly inspired by the doctrine of tyrannicide as taught by the Jesuits from the numerous attempts on the life of Elisabeth I in the 1580s, through the French Wars of Religion with the assassinations of the French kings Henry III and Henry IV, to the deeds of Damiens and Malagrida. The idea of a continuous chain of Jesuit-inspired regicides was contained not only in Les Jésuites criminels, but also in many other writings and by several engravings.

For instance, the anonymous image Quelques unes des conjurations des Jésuites mises en ordre chronologique contains a commemorative plaque with inscription for every known assassination attempt since 1581. The artist even had the foresight to leave some blank plaques for future crimes of the Jesuits. Other engravings depict Gabriele Malagrida, the key figure of Pombal's anti-Jesuit narrative, as a regicide.

contains a commemorative plaque with inscription for every known assassination attempt since 1581. The artist even had the foresight to leave some blank plaques for future crimes of the Jesuits. Other engravings depict Gabriele Malagrida, the key figure of Pombal's anti-Jesuit narrative, as a regicide. A small etching portrays the Jesuit as a hypocritical priest hiding a dagger under his rosary beads and crushing a crown with his feet, while the caption reveals his dark thoughts: "Mes mains ont un poignard avec un chapelet. / L'un est pour tromper le vulgaire, / L'autre, pour le plonger dans le coeur téméraire / De tout tyran qui nous déplaît."

A small etching portrays the Jesuit as a hypocritical priest hiding a dagger under his rosary beads and crushing a crown with his feet, while the caption reveals his dark thoughts: "Mes mains ont un poignard avec un chapelet. / L'un est pour tromper le vulgaire, / L'autre, pour le plonger dans le coeur téméraire / De tout tyran qui nous déplaît."

Tyrannicide was not the only subject the anti-Jesuit authors of the 1760s dwelled upon, though it was the main topic. It became especially effective when combined with other anti-Jesuit stereotypes such as their secrecy, their illicit trading business or their lust for power. Taken together, these allegations suggested a vision of the Jesuit order as a diabolical machine working for the expansion of its own power to the disadvantage of both ecclesiastical and lay authority. Indeed, many anti-Jesuit writings effectively advanced a conspiracy theory. Even if the word "conspiracy" rarely appeared in the debate, the idea that the order was plotting to establish a "universal monarchy" was quite common. One characteristic feature of this conspiracist view was the assumption that the order was in reality completely different from what it appeared to be, both in terms of its official goals and its internal organisation.43 This idea had already been the central message of a famous seventeenth-century pamphlet entitled Monita secreta, which was then edited and re-edited throughout Europe. The allegation of secret instructions sent by the Jesuit superiors to some chosen members of the order was intended to compromise the Society of Jesus by revealing its "true" immoral and even criminal aims and methods.44 Pombal and many of his contemporaries took up this central idea and declared that the order had secret instructions to which only to a few chosen members were privy, while the others were governed by rules unknown to them. The ordinary Jesuit who had taken an oath of blind obedience was therefore a potentially dangerous instrument in the hands of his superiors. This idea was widely discussed, some authors even affirming that the secret instructions were hidden in Rome and that not even the Pope knew exactly what the Jesuits were up to.45

In addition to this, the anti-Jesuit authors systematically misinterpreted the order's official texts by treating stated ideals as objective realities. For instance, the call for unity found in the constitutions led anti-Jesuit authors to conclude that all Jesuits ipso facto followed the same line and were the same the world over. This conspiracist view presented the Society of Jesus not as a collection of individuals, but as a superhuman army in which all march in unison to the commands of the general in Rome. This depiction of the Jesuit order was presented not only by Jansenists, but also by philosophes. According to d'Alembert, the Society of Jesus was characterized by an "esprit d'invasion" barely covered by a "mask of religion".46 The Jesuits had always been "pleins du projet de gouverner, & de gouverner par la religion", and had at all times followed a "politique uniforme & constante".47 D'Alembert even takes up the ideas of the Jesuits' excessive pride, their continuous spying on one another and their perfect internal unity, coming to the conspiracist view that "tous à la fois sont mis en action par ce ressort unique, qu'un seul homme dirige à son gré; & ce n'est pas sans raison qu'on les a définis une épée nue dont la poignée est à Rome."48

In spite of the philosopher's skilful handling of anti-Jesuit stereotypes, as a conspiracist d'Alembert still could not match the Jansenist authors of the very famous Histoire générale, which had such a strong influence on the French parlements. Le Paige and Coudrette presented the most accomplished anti-Jesuit conspiracy theory of the debate. Their argument contained two main accusations: the Jesuits were a despotic organization and they had systematically subverted the French political system. Describing the Jesuits like an army in which the general stood above all others and even above the rules of the order, they suggested that the Jesuits had settled in France against the will of the parlement, which was forced by the king to admit the order and which consequently felt obliged to remonstrate with the king on the issue. The Jesuits had thereby driven a wedge between the king and his parlement, which was fatal for the bien public.

Le Paige and Coudrette's conspiracist depiction of the order was not only a masterpiece of anti-Jesuit publishing, but also had evident anti-absolutist political implications. Their description of the "despotic" internal organization of the order and the manner in which it established itself in France implies a contrasting vision of how an ideal state should be ordered. In this vision, the parlements, and not the king, have the final word on any important matter concerning the kingdom, as the parlements represent the nation and are the guardians of the fundamental laws of the realm. Therefore the parlements are obliged to resist a king misguided by evil advisors and deceived by the Jesuits. A king who systematically bypassed the parlements would soon turn into a despot similar to the Jesuit General – this was a central message of the book. This anti-absolutist dimension of the Histoire générale fundamentally contributed to the constitutional crisis of the mid-eighteenth century, setting the French king and parlement in opposition to each other.

Conclusion: (Counter-) Enlightenment and the polarization of the European public sphere

Conspiracist thinking was not the preserve of the enemies of the Jesuits. The defenders of the order were just as susceptible to this kind of reasoning as their opponents. They warned against 'ces hommes puissans, dont les effets combinés annoncent depuis long-tems une conjuration formée contre le Trône et l'Autel'.49 'These powerful men' may refer either to the philosophes or the Jansenists. Most orthodox Catholics hardly differentiated between the two in any case. According to a quite famous Catholic conspiracy theory which was revived during the debates of the 1760s, the early Jansenists were actually deists who had conspired to ruin the Christian faith and the Catholic church by setting moral standards so high that they simply put off the average Christian.50 The resulting spread of "esprit d'indépendance", "libertinage" and "vaine philosophie", it was argued further, was responsible for the current calamities of the church.51 Supporters of the Society of Jesus usually agreed that the offensive against the order was only the first step towards the complete ruin of the church, which would then result in the total collapse of political and social order:

Voilà ce qui fait tant de rebelles, & de-là tant d'incrédulles; car quand une fois on a secoué le joux [sic] de l'obéissance & de la soumission dûe à l'Eglise la foi s'éteint & devient morte & il n'en coute pas plus de ne rien croire, que de se révolter contre toutes les Décisions qui contrarient nos penchants …52

Some authors were quite sure that the fall of the Jesuits would soon lead to the reign of philosophy, a nightmarish vision according to a rather sarcastic "dame philosophique" writing in 1762:

Société avide d'honneur & d'estime, que voulez-vous de mieux? L'ébranlement de l'Autel n'honore-t-il pas assez votre chûte? N'est-il pas glorieux de ne plus être, quand on est tombé avec tant d'éclat? Nous allons être Philosophes; tout ce qui ne l'est pas, vous donne déjà des regrets & des larmes, que la seule Philosophie pourra essuyer. … Siecle avenir [sic], vous jouirez du fruit de notre sagesse. Encore un instant: la Société tombe; & le regne de la Philosophie, élevé sur ses ruines, ne finira plus.53

Paradoxically, the Jansenists completely agreed with their opponents that faith and church were in a critical state. But where the Jesuits' supporters saw an unholy alliance of Jansenists and philosophes as the origin of this decay, the Jansenists identified a tacit cooperation between Jesuits and unbelievers. In the Jansenists' opinion, the Jesuits' lax morals had paved the way for deism and libertinism:

Mais n'est-il pas visible que la Morale licencieuse des Casuistes conduit aussi d'une autre manière, qui n'est pas moins dangereuse, à l'incrédulité & aux blasphêmes contre la Religion? Quelle idée veut-on qu'un libertin se forme de la sainteté du Christianisme, quand on lui en présentera la Morale sous une forme aussi méprisable & aussi manifestement indigne de Dieu?54

Addressing d'Alembert and his fellow philosophes directly, one Jansenist even implied that there was no real difference between Jesuits and philosophes, and that the latter were even more at fault:

Leurs principes, leurs maximes sont les vôtres, leur morale est la vôtre, jusqu'au régicide inclusivement. L'unique différence, c'est que leur politique & leur intérêt les portent à arborer un certain dehors de religion, au lieu que vous affichez hautement l'impiété. Qu'est-ce qu'un vrai Jésuite, sinon un Philosophe déguisé; & qu'est-ce qu'un Philosophe, sinon un Jésuite manifeste?55

This statement of Louis-Adrien Le Paige clearly marks a shift in the Jansenists' publicity battle. From the mid-1760s on, the parti janséniste turned its attention from the already defeated Jesuits to the philosophes, whose success in influencing the European public had become more and more apparent. In doing so, the Jansenists added their voice to those in the European public sphere who deplored the decay of religion and faith and who collectively gave rise to what Darrin McMahon has called an "anti-philosophical" discourse.56 Paradoxically then, the European debates about the Jesuit controversy contributed less to the dissemination of enlightened ideas than they did to the formation of an anti-philosophical discourse that would become an important element of the counter-enlightenment in the late-eighteenth century. The fact of the media event nonetheless prompted the enlightenment, and all participants contributed to this, whether intentionally or otherwise. Indeed, the mere fact that a transnational public debate on such central topics as religion, faith and politics continued for several years surely accelerated the polarization and the politicization of the European public. The media event resulting from the suppression of the Jesuits may therefore be considered as much a phenomenon of the counter-enlightenment, as a symptom of the enlightenment.