Introduction

The "Italian Model" or "Modèle italien" is perhaps the oldest and most common in our received tradition of writing histories of this type of narrative because Fernand Braudel (1902–1985) published his history of the Italian Renaissance in French under the title Le modèle italien. Therefore, instead of summarizing what already exists (Braudel's book), this article will take a historiographical detour. I will try to reveal the historical roots of the 'Model-Model': how was the question of the diffusion of Italian Renaissance and Baroque culture across Europe rooted in pre- and post-World-War-II historiography? What were the implicit and explicit assumptions underlying such a project between the 1930s and the 1980s? Part 2 brings us to a discussion of how such a historical narrative can still be adopted today. The third section then defines a narrow concept of the "Italian Renaissance as Model". In part four, I will give a very short and rough sketch of what could be a History of the Italian Renaissance as model for and in Europe.

The Model of Model History: Braudel's Modèle italien revisited

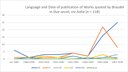

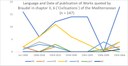

Though he is not explicitly mentioned in the introduction to European History Online, it was Fernand Braudel who served as a starting point1 for what was to be conceived as a range of articles dealing with "The Formation of Models and Stereotypes in Intercultural Transfer Processes".2 His Le modèle italien was the title of the French publication (1989) of an overview chapter regarding the impact of the Late Italian Renaissance and Baroque outside of Italy, 1450 to 1650, within the larger context of the 1974 Einaudi History of Italy, edited by Ruggiero Romano (1923–2002) and Corrado Vivanti (1928–2012).3 Braudel's book with this new title was taken in its German translation (Modell Italien) anew as a starting point for histories of cultural transfer, diffusion and references in the early 2000s.4

The original Italian title in the Einaudi volume was Due secoli e tre Italie (Two centuries and three Italies) under the header of LʼItalia fuori d'Italia (Italy outside Italy) which was probably proposed by Romano and Vivanti as Braudel was sharing this with Jacques Le Goff (1924–2014), who was responsible for a complementary chapter on medieval history in that volume. Braudel's task in this work was not to write an overview of the Italian Renaissance or about Italian history from the late 15th to the 17th century as such, but with regard to the rest of Europe: what was Italy's impact on the rest of Europe? It seems that Braudel was inspired by that task and integrated it into his own life-long historical approach starting in the 1930s. For his unachieved Identité de la France, Braudel planned to write a fourth part similarly entitled "La France hors de la France", and from what we will see below, we might guess that this would have been a history of the diffusion and impact of the French enlightenment in Europe during the 18th century.5 The term "model" only entered the vocabulary in the 1989 French text of Due secoli e tre Italie ("Tout cela, quels que soient les images ou les mots auxquels, faute de mieux, recourt notre raisonnement (diffusion, rayonnement, modèle, enseignement, Lumières [diffusione, irradiamento, magistero, lumi – "modèle" is present only in the French translation]6, dessine un seul problème".)"7

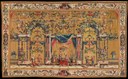

Braudel's 1989 book and its 1974 Italian precursor cannot be read differently than in a certain stereoscopy with the sixth chapter of the second book of the 1949 La Méditerranée on "Civilizations". The repetition, if not identity, of thoughts, formulations and events makes the major problem evident. In that chapter of the Mediterranean, Braudel had inquired into the "Mediterranean radiations or influences" (rayonnements méditerranéens). The "Baroque" was the central example of what were the somehow sublime cultural manifestations of "the Mediterranean" in the North. The major question and the answers are the same: when and how do civilizational or cultural entities interact? "Rayonner, donner, c'est dominer",8 so the Mediterranean culture is a model, has an impact and is emulated, because it is (or it is perceived somehow as) superior, according to Braudel. His second major remark that would be repeated in the 1974 Modèle is that, apparently, cultures are somehow "radiating" the strongest when their own pinnacle of strength has already passed. The Mediterranean is "illuminating" the rest of Europe – England, France, the countries north of the Alps – just at the moment of its own decline,9 just as Greek culture had illuminated late Republican and early imperial Rome, while being itself already dominated by the new Empire. The Mediterranean ''culture'' would have influenced the Northern and Western cultures when they were taking over world domination during the global shift from a Mediterranean to an Atlantic power axis.

One can find nearly the same sentences, exchanging the word "Mediterranean" with the word "Italy" or "Italian Renaissance" in the 1974 chapter/book. There, in the final methodological part, Braudel first engages with Georges Gusdorf (1912–2000) and then relates a 1945 conversation in the Sorbonne with Georges Lefebvre (1874–1959), the famous historian of the French Revolution (La grande peur), during which Lefebvre had stated that probably "power and cultural radiation are two faces of one and the same phenomenon". Braudel was of different opinion: he thought that there would be something like a historical law that "cultural radiation" is a phenomenon that postdates the peak of real power, a "post-seasonal phenomenon" ("un phénomène d'arrière-saison"), and, after having dealt with that for Italy in a period described as culminating point and then "decline", he argues that similar would have been true for the Spanish siglo d'oro (a 'radiation' postdating the Spanish real strength of the 16th century), for the French enlightenment of the 18th century (a 'radiation' postdating the real French power of the 17th century).10

Historiographical research on Braudel took off right after his death.11 A large number of contributions exist on Braudel's heritage on what concerns his geohistorical approach.12 Recently, even the legacy that fully fleshed German geopolitics (Karl Haushofer, 1869–1946) next to Friedrich Ratzel (1844–1904) and Paul Vidal de la Blache (1845–1918) has left on his concept of (maritime) space has been uncovered.13

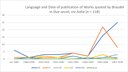

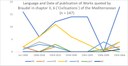

However, fewer efforts have been made to decipher the roots and the epistemological contexts of discussions in which Braudel was embedded when writing about cultural history as in our case. As Heinrich Lutz (1922–1986) maintained in 1982, it is worth checking the footnotes of Braudel.14 Doing that, several important observations can be made: First, it is important to see how the Mediterranean was a French-German book in its making, due not only to the importance of German pre- and inter-war geographical and historical research, but also to his enforced reliance on the libraries in Mainz (1940–1942) and Lübeck (1942–1945).15 At that time, Italian authors were rarely used. After his re-establishment in Paris, things certainly changed. Now, for the Modèle chapter/book, it was Italian research that led behind the French [

[ ].16

].16

While the Mediterranean is a book basically rooted in the inter-war questions and its research, the Modèle's bibliographical data turns out to be "newer" on the one hand, but also more repetitive, using an essay style for many pages and topics he was now more or less re-selling, without many footnotes at all. The larger amount of recent books he digested from the 1950s to the early 1970s were works on cultural history he needed to "make himself expert of" (Galileo, the Baroque question), being more of an economic historian by education.

Where he (rarely) cites primary sources from the archives and more specialized recent works, and where he is at home, is always the economic history of Italy, while he somewhat absorbed information in third-hand mode from second-hand syntheses for what should have been the cultural core of both, the 1974/1989 Modèle as the 1949 civilization chapter in the Mediterranean. Neither in the Mediterranean nor in that book allegedly on "the Renaissance", do we see Braudel as a first-hand reader and interpreter of humanist authors in current editions, in dialogue with Italianists on a given passage of an author (set aside here and there a quote from Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527), Giovanni Botero (1544–1617) or Jean Bodin (1529–1596). He never used a hermeneutical approach. Perhaps a similar approach to the humanists' writing would be the old type of historicism as once inaugurated by Friedrich Meinecke (1862–1954).

One can single out certain works that seem to have been – sometimes surprisingly – more important – just between the time of writing the Mediterranean and the Modèle – for sharpening the major question about conjunctures of civilizations, "cultural radiation" and the functioning of "models". Some works were even rooted in fascist and the Volk-history tradition. Then, next to the dialogue with his immediate Paris colleagues such as André Chastel (1912–1990) (4e section de l'École des Hautes Études, 1951–1955, after 1955 at the Sorbonne), with Alexandre Koyré (1892–1964) and Georges Gusdorf, Braudel seems to have received with special interest some post-Marxist authors, converted either to forms of Liberalist or other idiosyncratic forms of historical thought which were common among war émigrés: Alexander Rüstow (1885–1963) (during the war an émigré in Istanbul), Leonardo Olschki (1885–1961) (exiled to the US), and Frederick Antal (1887–1954) (émigré in London).

To measure grandeur, superiority and "cultural radiation" (Braudel/Rüstow)

Braudel's question of the relationship between the "grandeur" of a civilization, nation or people and the processes of "radiation" is introduced from the first footnote on with reference to the pre- and inter-war discussion on similar questions, quoting Arthur de Gobineau's (1816–1882) idea that "every human society" has its decline and arguing that there can be "Renaissances".17 He also refers to one of the volumes promoted by Fascist Italy's Foreign Ministry and the Italian Royal Institute of Archaeology and Art History on the Opera del Genio italiano all'estero. Started in 1939, three years after Benito Mussolini's (1883–1945)[ ] invasion of Ethiopia, this multi-volume work traced the paths of Italian medieval and early modern "colonizers" (Genovean, Venetian empires

] invasion of Ethiopia, this multi-volume work traced the paths of Italian medieval and early modern "colonizers" (Genovean, Venetian empires ),18 of Italian artists and engineers abroad. This resonated therefore with Braudel's task still in the 1970s to write a history of "Italy outside of Italy".

),18 of Italian artists and engineers abroad. This resonated therefore with Braudel's task still in the 1970s to write a history of "Italy outside of Italy".

This 1939 series was part of the overall tendency of Italian Fascism to revitalize the medieval and rinascimental "Italianità" as its heritage and to mirror present and future paths of outreach, expansion and "grandezza" in past ones, eventually to stimulate another "national regeneration" (after the Renaissance and Risorgimento). This was a discourse ideologically vaguely shaped and it survived, somewhat easily, into 1950s.19 The question, how "a nation" could be "great", remain great, re-awake, and conquer other civilizations on a cultural as well as on a real military level, was still a question that Braudel asked in those terms quite similar to the old language, though as a historian and not as an ideologue.20

In what we therefore might recognize as a Cold War narrative of "nations as Models", Braudel first needed to explain the specific "grandeur" of the Italian Renaissance. Without that superiority, no "Italian radiation" would have been possible.21 At that central point, he quotes from Alexander Rüstow's Ortsbestimmung der Gegenwart a passage on the importance of urban culture within the developmental process of history. Rüstow had been first a socialist, but had then belonged, with Wilhelm Röpke (1899–1966), Alfred Müller-Armack (1901–1978), and Friedrich August Hayek (1899–1992) and others, to the founding fathers of "ordo-liberalism", merging elements of a doctrine of authoritative state functions with a liberalist credo whose time would come after 1945.22 Rüstow built his economic theory on a large philosophico-historical work written during his Istanbul exile, which tried to explain the formation of complex societies by way of successive "overlayings or dominations (Überlagerungen)" of one tribe above the other, of a conquering state or empire above each other, of one class above the other, thus providing a complete narrative of European history from Ancient Greece to the present. The Durkheimian division of labor as the base of modern societies is only possible by freeing smaller more specialized parts of a society from basic work done by a larger number of unspecialized parts. The city was, for Rüstow, the central place of enacting this so-called "law of the culture pyramid": there must be a larger (metaphorical, social) surface area to enable a cultural height, a cultural or noble elite that dominates workers or slaves.23 The historical part on "Gothics and Renaissance" starts with the place of the city in European history. The city and its social structure create the conditions for lifting the culture "according to the law of the pyramid".24

Rüstow described the process Braudel was interested in – the Renaissance's European wide diffusion – as one of the "Überlagerungen" of a foreign culture over native ones due to the superior height gained.25 Translated into Braudel's thought, we might say, a 'radiating' Model must be on the top of the civilizational pyramid of a given period, which was for him the question of how to measure the "grandeur" of a civilization or of successive (Mediterranean, Italian, Dutch, English, French...) "grandeurs" within History. When it comes to the question of historical comparison, he continues to speak of "domination" and a dominating civilization in these contexts.26 Already in the Mediterranean, he reflected that there must be some superiority of one society above the other to be able to give, still in terms of a loosely digested "théorie du don".27 In the 1974/1989 version, he became even more pseudo-sociological: He reasoned about the relationship between a larger space dominated (the outside) by a smaller, privileged space (the inside) to explain the "height" or the functioning of the "grandeur" in state of radiation.28

Cultural diffusion and its meaning (Braudel/Antal/Olschki)

A further question was that of the real seat of the alleged Renaissance culture, taking Florence as central example, and taking here Frederick Antal as guide. The Hungarian Marxist Antal was member of the short-lived Budapest Republic in 1919, then member of the Vienna circle, faithful disciple of the Marxist esthetics of Georg Lukács (1885–1971), and emigrated to London, where he published the major work on Florentine culture and the question of the relationship between social class and art, between client and artist with regard to Florence, that Braudel used.29 What Braudel took from him in the subchapter "the height of the society" ("Le haut de la société"), was the doctrine that it was only a very tiny Florentine upper class that was ordering and paying for the art that became the expression of this proto-bourgeoisie culture.30 Braudel could use this to explain how this tiny small circle, ready to become nobles (Medici) and ready for migrating and taking refuge themselves during the times of Italian crises at the Western and Northern European courts, was the very agent of diffusion and of cultural transfers. The reason why "Italian" Renaissance and style was implanted into Western and Northern European court culture,31 the narrative of the "peak" of the urban culture that grew, could be linked with a post-Marxist narrative of a division of society in economically determined strata. Combining that with the narrative of crisis helped to explain the movement of diffusion, so to say the spread of what was cut off at the peak of the homegrown development.

The other, "Republican" and popular part of Renaissance culture and its spread, could be encapsulated by Braudel referring mostly to Music and the Commedia dell'arte actors that travelled through Europe, influencing the other European cultures, inaugurating emulation everywhere. Among others, Braudel refers to Leonard Olschki, for whom "the music becomes [became] the only free and autonomous manifestation of the artistic life of the Italian people". He was interested in music as "dominating the Baroque, because it had dominated Italy before it governed the world"32 Olschki, the important Polish-German art historian, immersed (between 1909 and 1932) into Heidelberg intellectual life with Ernst Robert Curtius (1886–1956), Heinrich Rickert (1863–1936), Karl Jaspers (1883–1969), Ernst Troeltsch (1865–1923), Alfred Weber (1868–1958) and Max Weber (1864–1920)[

that travelled through Europe, influencing the other European cultures, inaugurating emulation everywhere. Among others, Braudel refers to Leonard Olschki, for whom "the music becomes [became] the only free and autonomous manifestation of the artistic life of the Italian people". He was interested in music as "dominating the Baroque, because it had dominated Italy before it governed the world"32 Olschki, the important Polish-German art historian, immersed (between 1909 and 1932) into Heidelberg intellectual life with Ernst Robert Curtius (1886–1956), Heinrich Rickert (1863–1936), Karl Jaspers (1883–1969), Ernst Troeltsch (1865–1923), Alfred Weber (1868–1958) and Max Weber (1864–1920)[ ], and forced to emigrate from Rome to the US in 1938 because of his Jewish origins, was one of the best connaisseurs of medieval and Renaissance art specializing on early relationships between Italy and the Far East (China).33 Olschki's book starts in a quasi-mythical state of origins of Italy and the Italian people in its geo-natural conditions, and then moves through Roman, but mostly medieval and Renaissance history until around 1600, banning nearly the whole "modern" history of 19th/20th century Italy from the text except for a comparatively short epilogue. For Olschki, in fact, music and comedy remained the only place where the Italian "spirit" attempting for "universal" dimensions remained vital after the Spanish and later Austrian domination suffocated the liberal spirits once alive in Renaissance times.34

], and forced to emigrate from Rome to the US in 1938 because of his Jewish origins, was one of the best connaisseurs of medieval and Renaissance art specializing on early relationships between Italy and the Far East (China).33 Olschki's book starts in a quasi-mythical state of origins of Italy and the Italian people in its geo-natural conditions, and then moves through Roman, but mostly medieval and Renaissance history until around 1600, banning nearly the whole "modern" history of 19th/20th century Italy from the text except for a comparatively short epilogue. For Olschki, in fact, music and comedy remained the only place where the Italian "spirit" attempting for "universal" dimensions remained vital after the Spanish and later Austrian domination suffocated the liberal spirits once alive in Renaissance times.34

The third major cultural form that Braudel addressed next to Renaissance culture and Baroque art, were the emerging sciences. Nevertheless, in the chapter on Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), the only point for his own argument is to conceive of "science in Italy" as a question how to explain the apparently evident "decline of Italy" between 1633 (the trial against Galilei) and 1670 (first signs of early enlightenment). Huge parts of the discussion about the developments from Aristotelian to early experimentalist views (Padovan school), of the Italian accademia culture, of the interplay between engineering "tacit knowledge" craftsmanship, visual art and a culture of innovation as was discussed in parts of the literature on humanism and the Renaissance of his times, and more so today, do not find a real place in his narrative. All in all, the "content" of Renaissance and humanism remained underexposed and pale. This closer look of the sources and the idea behind Braudel's Modèle italien might have cleared the path to discern problems and the tacit implications of the figure of thought of "Model x" history narratives.

Is a History of "National" or "Civilizational Models" still possible today?

Braudel, just as Olschki, seems to have been convinced that, at least within the framework of Modern history, each civilization or nation has more or less only "one" moment of grandeur – perhaps also to avoid an unwilling copy of post-fascist Terza-Roma ideas (Ancient Rome, Papal and Renaissance Rome, Mussolini's Rome). For them, Modern World History or perhaps even the process that today we would call "globalization" in its skeptical perception of "losing" diversity and plurality,35 was structured by a succession of leading civilizations or nations, something like an always ascending translatio imperii, from the Italian to the Spanish to the Dutch and French to the British to the American "moment" of reaching that grandeur that is necessary to be a "radiator". Explicitly, Braudel denied that, in his own days of the 1970s, neither Italy nor even France would be in possession of "grandeur". Perhaps (and only perhaps) Europe as a whole might count as such in the near future next to the US, but he sounds skeptical about that.36 Therefore, while dwelling briefly on the effect of Italian mass immigration into the US during the 19th century and in other parts of the world as a major new phenomenon of "spreading" and cultural diffusion from Italy, he thought this to be a sign of weakness not worthy of investigation, at least not on the same categorical level as the "radiating" power of the Italian Renaissance in the 15th/16th century.

How would we approach this today? A first reaction could be very negative: are we not going back, with the "Model x" narrative, behind all methodological post-Braudelian discussions during the 1980s about cultural transfer, about prioritizing the point of view of the culture of reception instead of reifying the diffusionist regard for the "glorious" light spreading out from a Louis XIV (1638–1715), a Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) or a Machiavelli, illuminating other countries and cultures?37 Does the idea of World History structured by a succession of "leading" Model civilizations not risk to be extremely post-Hegelian and teleological, re-telling, in other words, the story of History's Geist that moves and manifests itself through and across peoples' fates?

On another level of methodological interrogation, one might ask how the "Model" narrative is to be distinguished from the history of reception, imagologies, from hybridization and from lieu-de-mémoire-narratives, and from histories on the diffusion and reception of consumer culture: Does the neo-rinascimental style chosen in some 19th century cities belong to the "Italian Model/Model Renaissance" story or not? Instances might include the Munich Feldherrnhalle on the Odeonsplatz, erected in 1841/44 by Friedrich von Gärtner (1791–1847), copying exactly the 15th century Florentine Loggia dei Lanzi

on the Odeonsplatz, erected in 1841/44 by Friedrich von Gärtner (1791–1847), copying exactly the 15th century Florentine Loggia dei Lanzi , the Copenhagen neorinascimental style of the harbor building at Nordre Toldbod

, the Copenhagen neorinascimental style of the harbor building at Nordre Toldbod , copying (in 1868–1869) Raffaelo's Florentine Palazzo Pandolfini

, copying (in 1868–1869) Raffaelo's Florentine Palazzo Pandolfini . Is the story of the worldwide reception of Italian Pizza since the 19th century a less mighty one than the history of the reception of Machiavelli?38 And does the story of the reception of Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) and Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) belong to a post-Model-Italy period, less important, less mighty, while the reception of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525–1594) and Commedia dell'arte

. Is the story of the worldwide reception of Italian Pizza since the 19th century a less mighty one than the history of the reception of Machiavelli?38 And does the story of the reception of Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) and Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) belong to a post-Model-Italy period, less important, less mighty, while the reception of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525–1594) and Commedia dell'arte belongs to that true period of Italy as a Model for all other civilizations?

belongs to that true period of Italy as a Model for all other civilizations?

First, in accordance with Braudel, as well as with post-postcolonial thought,39 I would state that there were historical differences between some forms of "superior/inferior" just as there were differences between the colonized and the colonizers. Those differences are empirically fluid, hard to define and exist perhaps only at a given moment and in the perception and conviction of actors on one level or on a second definitional level on the third observer's side. Speaking thus in general, it is not at all easy to decide if a volgare (vernacular Italian) humanist treatise by Machiavelli or Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) is "superior" to a late scholastic Latin treatise taught by Gabriel Biel (1418–1495) in Wittenberg University, both around 1500. The question remains, why and how, was there no significant Biel reception in Italy,40 whereas in the long run Italian volgare humanist texts were received, re-Latinized in academic German-Latin contexts, and how around 1600 what was then taught in Wittenberg liberal arts faculties (Politica, Ethica) was a hitherto uncommon mix and amalgam of those forms unconnected and still disparate around 1500?41 And this, although Biel's late-medieval nominalism was highly sophisticated and perhaps even thought to be "superior" in terms of standard of university education and logical craftsmanship at that time, in comparison to Machiavelli who hardly had a higher university education.

To use, as basically an early modernist, with a light smile, a certainly simplistic Ramistic scheme, I would propose to distinguish like that: During processes of communication, cultural items are perceived either as new or old  . Nearly all of the examples mentioned above can be conceived as part of a history of reception. Its methodological paths have been discussed in hermeneutics since the times of Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002) and Hans Robert Jauß (1921–1997). However, if Machiavelli, Giovanni Botero, Angelo Poliziano (1454–1494) Galilei, Scipione Ammirato (1531–1601), Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) or any other was received roughly between the Braudelian 1450 and 1650, he was received as somehow "new" or at least as part of what is more or less present, helpful and usable in that present as a current part of it. The historian might discover that it was not new (that there are, for instance hidden Thomist transcripts in the alleged new message and so on). Vice versa, the humanists could just claim to revive antiquity – but their product as authors of revised texts and artefacts was new at that moment, and for the communication process itself, both forms of relativization are here of secondary importance.

. Nearly all of the examples mentioned above can be conceived as part of a history of reception. Its methodological paths have been discussed in hermeneutics since the times of Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002) and Hans Robert Jauß (1921–1997). However, if Machiavelli, Giovanni Botero, Angelo Poliziano (1454–1494) Galilei, Scipione Ammirato (1531–1601), Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) or any other was received roughly between the Braudelian 1450 and 1650, he was received as somehow "new" or at least as part of what is more or less present, helpful and usable in that present as a current part of it. The historian might discover that it was not new (that there are, for instance hidden Thomist transcripts in the alleged new message and so on). Vice versa, the humanists could just claim to revive antiquity – but their product as authors of revised texts and artefacts was new at that moment, and for the communication process itself, both forms of relativization are here of secondary importance.

If the Loggia dei Lanzi was copied in 19th century Munich, it was consciously reproduced in a quasi pre-postmodern way of style imitation with a distinct historicist consciousness of how old that is. It stood in the 19th century in a similar historico-cognitive distance from the Renaissance as stood antiquity to the 15th century Florentines . This is not the same process, but a Renaissance-Renaissance, and in accordance with Braudel one can ascribe the first process as belonging to the "History of a Model", and the other to some other kind of historical narrative, say a History of lieu de mémoire or of historical references in that case. At the latest, when the historicist term of "Renaissance" was coined around the middle of the 19th century, it was not perceived as belonging to the observer's present time, it was old.42

. This is not the same process, but a Renaissance-Renaissance, and in accordance with Braudel one can ascribe the first process as belonging to the "History of a Model", and the other to some other kind of historical narrative, say a History of lieu de mémoire or of historical references in that case. At the latest, when the historicist term of "Renaissance" was coined around the middle of the 19th century, it was not perceived as belonging to the observer's present time, it was old.42

19th century philology started to conceive of Machiavelli in purely historicist terms, to understand, for instance, the diffusion of his De principatibus in manuscript as part of a certain Republican culture of dialogue with the ascendant Medici still rooted in the same culture. Machiavelli was then a prototype of humanist vernacular lay culture of the years 1498 to 1527, certainly not received as new in those 19th-century circles. However, certainly, Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814), Mussolini and Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) could "actualize" Machiavelli. For one, "the Prince" was the national state,43 for Mussolini it was even the totalitarian state44, and for Gramsci, "the prince" was even the communist party.45 This was not just a lieu de mémoire or a way of referring to medioevo (and Renaissance), yet it is still part of a large history of reception. Perhaps one does good to define this a history of ideological re-use or ciphering. To close the circle: perhaps the first Renaissance belongs, in its non-antiquarian but ideological forms, itself to a form of ciphering antiquity through someone like Machiavelli just as he claimed to revive and to comment upon Livy (59 BC–AD 17). Once such a cipher has been created, it can become itself a part of a reception process and a Model perceived, and, after some time, it can become part of a lieu de mémoire and eventually of a new process of ciphering history. Not everything should be called "a Model", thereby confusing reception history and all other forms of narratives, and not distinguishing between the different phenomena.

in manuscript as part of a certain Republican culture of dialogue with the ascendant Medici still rooted in the same culture. Machiavelli was then a prototype of humanist vernacular lay culture of the years 1498 to 1527, certainly not received as new in those 19th-century circles. However, certainly, Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814), Mussolini and Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) could "actualize" Machiavelli. For one, "the Prince" was the national state,43 for Mussolini it was even the totalitarian state44, and for Gramsci, "the prince" was even the communist party.45 This was not just a lieu de mémoire or a way of referring to medioevo (and Renaissance), yet it is still part of a large history of reception. Perhaps one does good to define this a history of ideological re-use or ciphering. To close the circle: perhaps the first Renaissance belongs, in its non-antiquarian but ideological forms, itself to a form of ciphering antiquity through someone like Machiavelli just as he claimed to revive and to comment upon Livy (59 BC–AD 17). Once such a cipher has been created, it can become itself a part of a reception process and a Model perceived, and, after some time, it can become part of a lieu de mémoire and eventually of a new process of ciphering history. Not everything should be called "a Model", thereby confusing reception history and all other forms of narratives, and not distinguishing between the different phenomena.

Are we speaking then about the History of an Italian Model, of a Renaissance as Model, of an Italian Renaissance Model? That Braudel could treat Galilei only as a part of his question about the duration of Italy as 'sending culture' and of Italy's decline – without looking into and interpreting the core of Galilei's scientific content itself, is telling.46 The ordering principle of his tacit Model-Model was World History as a history of civilizational progress with the actor "nation" or "civilization", it was not about other themes (the history of science of instance). This seems to merge somewhat the succession of leading nations (Italy, Spain, Netherlands, France, Britain, Germany, the US) within Europe and then the World with the fluid semantics of old-European periods (Antiquity, Middle Ages, Renaissance, Enlightenment, Full Modernity). Probably, it would be wise to dismiss the type of national model histories tout court: "The Italian Model" would necessarily have to comprise the whole sequence through time that one might evoke briefly by the metonymically meant succession Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) / Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375) – Florentine Renaissance – Cesare Beccaria (1738–1794) / Giambattista Vico (1668–1744) – Enlightenment – Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882) / Camillo Benso di Cavour (1810–1861) / Verdi – Pizza / Ferrari / La Dolce Vita: Such a narrative would have to be explicit about a (necessarily highly questionable) concept of "nation" and an "Italian people" that serves as a stable actor of History through time. But this creates huge problems, as each historian today is well aware that the constructions of Italianità and of 19th century "Italy" as such are just an effect of many of such cultural processes of referencing, ciphering, revitalization, construction. This leads methodologically to a slight form of tautology: on the one hand one reifies in the end a transhistorical concept of nation that one needs as frame for the whole story, on the other hand one wants to write a history of model(s) in given moments that would instead belong to a form of challenging such stable ideas of cultural and social units. This would repeat for a different type of historical narrative a choice quickly criticized in the 1990s concerning the first generation of lieux de mémoire narratives, starting with Pierre Nora's (born 1931) volumes. Clustered and organized according to the category of nations, this was the beginning of unnecessarily giving away much of its implicit critical potential if taking care of divided and shared memories, of transfers and movements of ideas, references and topoi beyond the borders of nationality. The concentration on a given period and on how cultural products were diffused and received "as new" seems therefore helpful to avoid some traps and complexities.

The Italian Renaissance as a Model

If we dismantle Braudel's term of "grandeur", being somehow similar to Rüstow's peak of civilizational development in search for its epistemological core, it stands where in a Model narrative one has to explain why a whole set of ideas, texts, artefacts and items were received outside their original context as new and as valid, helpful or important or somehow necessary enough to appropriate them or at least not to ignore and reject them.47 Even cultural transfer scholars would not deny that there were certain conjunctures and dominating tendencies and directions of cultural flows.48 Taken as such, behind that idea of a "grandeur" stands that of the aggregative quality of a "culture" predominantly 'sending' for some time and in a given larger context. It stands for the epistemic moment of attractiveness, evidence, convincing, matching, for the acceptability within a process of diffusion. This is not far away from the discussion about the relationship between the (first) emergence of an innovation and the conditions of its diffusion, implying all the problems that exist if one enlarges the realm of objects from merely technical innovation to such things as styles, music , painting, ways of writing in general. This leads to the next point: While it would be difficult to define in absolute "the" core of the Italian Renaissance, one has to at least dare to enumerate a set of central elements and characteristics. Only by that can one understand what was "the new" at the moment of its emergence even from the standpoint of a late observer. Thus the historian suggests what its attractiveness consisted of at the moment of its diffusion. One can always discuss the qualities of such a 'core' or deny – from a postcolonial or poststructural point of view on communication and hybridity – that 'a core exists at all'. However, in doing so, one will not be able to describe and analyze epistemic movements and transfers. In the very end, such an approach would banish change, development, movement and therefore History from History, and what remains would be a 'frozen' cultural-ethnological description applicable without distinction to each time, place and society. This is an option for scholars in the broad field of cultural hermeneutics, but not an option for someone who wants to write a History of Models.

, painting, ways of writing in general. This leads to the next point: While it would be difficult to define in absolute "the" core of the Italian Renaissance, one has to at least dare to enumerate a set of central elements and characteristics. Only by that can one understand what was "the new" at the moment of its emergence even from the standpoint of a late observer. Thus the historian suggests what its attractiveness consisted of at the moment of its diffusion. One can always discuss the qualities of such a 'core' or deny – from a postcolonial or poststructural point of view on communication and hybridity – that 'a core exists at all'. However, in doing so, one will not be able to describe and analyze epistemic movements and transfers. In the very end, such an approach would banish change, development, movement and therefore History from History, and what remains would be a 'frozen' cultural-ethnological description applicable without distinction to each time, place and society. This is an option for scholars in the broad field of cultural hermeneutics, but not an option for someone who wants to write a History of Models.

For me, at least one important element has always been the suggestion that new forms of (primarily long-distance) communication had effects on the epistemic level of perception of Renaissance men (and women) roughly between 1350 and 1530. The special mental world of writing down the spatial dimensions of the flows of commerce in merchant letters as known, for instance, from the Datini archives,49 is such a link between an epistemic level and a materially new form of communication that was not possible before the first paper mill in Italy was established. Thereby a second world of representation of the relevant economic world as a world of value flows, separated and somehow independent from the physicality of the goods themselves was created. A similar 'doubling' between the physical world and a stabilized form of representing the world's present state – not in terms of values, but in terms of actors and parameters that matter in the political sphere – emerged in the realm of political communication. The infrastructural cause for that epistemic change was the establishment of a reliable postal relay system (since ca. 1380) ,50 its first exclusive use for diplomatic dispacci communication (since 1450 ca. with the Sforza),51 and finally for early semi/quasi-public news communication (avvisi, since 1480/1550 ca.)

,50 its first exclusive use for diplomatic dispacci communication (since 1450 ca. with the Sforza),51 and finally for early semi/quasi-public news communication (avvisi, since 1480/1550 ca.) :52 The whole narrative of the "emergence of the earliest system of states" in Renaissance Italy is linked to that,53 because the "state" emerges as an epistemic function in the perception of those writers.

:52 The whole narrative of the "emergence of the earliest system of states" in Renaissance Italy is linked to that,53 because the "state" emerges as an epistemic function in the perception of those writers.

This form of communication triggered and substantially changed the form of observing: everyone observed the other as individual actor on a field or in a sphere which was represented in the thousands of dispacci, letters and then avvisi that were exchanged in a given rhythm of ambassadorial correspondence between the courts and cities.54 For both, the realms of economy and politics, there was a material change that is visible to everyone who has been in an Italian state archive where the number of buste with dispacci, semi-public and state letters, then avvisi, explode after a certain year . The same is true for the economic world, though, unfortunately, due to far less stable situations of archival transmission.55 And certainly, it was not just the increase in terms of quantity, but the quality and new forms of organizing the information (the separation of different merchant books attempting to order the information according thematic questions and directions of flows: incoming, outgoing values, insurances taken, credits given and taken etc.). Likewise, political communication was ordered in each court's or signoria's chancery roughly regarding the place of origin, after the establishment of residential agents or ambassadors.56 This became quite stable: a "state" and its stability is more or less the name for the aggregated perception that existed in each of those chanceries that there was a transpersonal actor about whose present situation news was constantly arriving. The end of a state's existence (because of being conquered and integrated into a larger one for instance, like in the Pisa / Florence case) is equal to the fact that this type of communication stops.

. The same is true for the economic world, though, unfortunately, due to far less stable situations of archival transmission.55 And certainly, it was not just the increase in terms of quantity, but the quality and new forms of organizing the information (the separation of different merchant books attempting to order the information according thematic questions and directions of flows: incoming, outgoing values, insurances taken, credits given and taken etc.). Likewise, political communication was ordered in each court's or signoria's chancery roughly regarding the place of origin, after the establishment of residential agents or ambassadors.56 This became quite stable: a "state" and its stability is more or less the name for the aggregated perception that existed in each of those chanceries that there was a transpersonal actor about whose present situation news was constantly arriving. The end of a state's existence (because of being conquered and integrated into a larger one for instance, like in the Pisa / Florence case) is equal to the fact that this type of communication stops.

One can try to define deeper and more precisely the changes of perception linked to that shift with regard to the form of writing and the narratives produced themselves57. Temporalities change, the whole famous idea that humanists "created" a new way of historical consciousness can be translated into the thesis that the way of newsletter communication and writing changed, first of all, the perception of the present (contemporaneity, Gegenwartshorizont). It also necessitated the conception of the past as similar past present states58 – which leads to the historia magistra vitae concept in its functional form that causalities and ways of political action can be emulated from antiquity because it is conceived to be similar.59 Studying the letters of Lorenzo de' Medici (1449–1492)[ ], one can indeed identify concepts such as the care for the whole of "Italy", meaning the aggregation of highly individually acting political players, caring for the security of that whole as well as first for the individual unit "Florence".60 Thinking in interdependencies, projecting, planning, calculating the action of others by analyzing the current flow of news, is training a thought in such causal and functional interdependencies that create and destroy alliances; it trains in measuring and calculating the "forces", the powers of the players. This is the germ of "states in numbers", of statistics,61 and it lets emerge descriptions for different forms and qualities of states and their relations (neutrality, sovereignty, small, big state, protection and security in a modern sense).62 Finally, this form of new perception creates a political sphere and 'reality' through this constant renewed representation, for which the actors became aware of lacking a method, a science to govern and to master it: an art or science for decision-making processes. That is what Machiavelli meant when he claimed that there was no science of politics transmitted from antiquity, while there were laws, the corpus iuris civilis and its tradition of commentaries transmitted for the lawyers and the Galen (129–199) – Hippocratic (460–370 BC) – Dioscorides (ca. 40–90) tradition for physicians. Renaissance men of politics had no functional political laws at hand, no theory that would guide their thoughts while analyzing this new form of political reality and perception.63

], one can indeed identify concepts such as the care for the whole of "Italy", meaning the aggregation of highly individually acting political players, caring for the security of that whole as well as first for the individual unit "Florence".60 Thinking in interdependencies, projecting, planning, calculating the action of others by analyzing the current flow of news, is training a thought in such causal and functional interdependencies that create and destroy alliances; it trains in measuring and calculating the "forces", the powers of the players. This is the germ of "states in numbers", of statistics,61 and it lets emerge descriptions for different forms and qualities of states and their relations (neutrality, sovereignty, small, big state, protection and security in a modern sense).62 Finally, this form of new perception creates a political sphere and 'reality' through this constant renewed representation, for which the actors became aware of lacking a method, a science to govern and to master it: an art or science for decision-making processes. That is what Machiavelli meant when he claimed that there was no science of politics transmitted from antiquity, while there were laws, the corpus iuris civilis and its tradition of commentaries transmitted for the lawyers and the Galen (129–199) – Hippocratic (460–370 BC) – Dioscorides (ca. 40–90) tradition for physicians. Renaissance men of politics had no functional political laws at hand, no theory that would guide their thoughts while analyzing this new form of political reality and perception.63

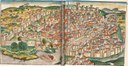

Things become more complicated if one wants to define similarly for the arts something like the "core" of rinascimental expressions and forms, which should be left to art historians. A first idea would be the "invention" of the perspective, allegedly first used and technically applied by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) in 1420 , and developed by Alberti. The mathematician Luca Pacioli (ca. 1445–1509) would have recalled around 1500 how mathematical abacus knowledge, techniques of measuring in mercantile and in architectural life, were combined here and transferred to the realm of art.64 The central point is again a shift in forms of representing reality, how spatiality and depth find a different form of expression. Active in it is a reflexive perception about how spatial distance presents itself to the observer's eye. Since Braudel, who relied for those questions on Chastel, further research has been done on that.65 While a causal link to a change of material communication seems more difficult to establish than in the case of politics, the central point is again a change in perception and reflexivity – with all following changes in the visual arts, in wooden furniture

, and developed by Alberti. The mathematician Luca Pacioli (ca. 1445–1509) would have recalled around 1500 how mathematical abacus knowledge, techniques of measuring in mercantile and in architectural life, were combined here and transferred to the realm of art.64 The central point is again a shift in forms of representing reality, how spatiality and depth find a different form of expression. Active in it is a reflexive perception about how spatial distance presents itself to the observer's eye. Since Braudel, who relied for those questions on Chastel, further research has been done on that.65 While a causal link to a change of material communication seems more difficult to establish than in the case of politics, the central point is again a change in perception and reflexivity – with all following changes in the visual arts, in wooden furniture , (not the least military fortification) architecture, where art historians are the better experts to trace the complex ramifications of intra-Italian emulation and the evolution and then of perception and transfer outside of Italy.66

, (not the least military fortification) architecture, where art historians are the better experts to trace the complex ramifications of intra-Italian emulation and the evolution and then of perception and transfer outside of Italy.66

A final point would be the transformation within "sciences", though the 1960/70s tacit consensus about what that meant for the times around 1500 is probably lost today. There was somehow a projection of Albert Einstein's (1879–1955) revolution of physics back onto Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Galileo which was guiding playwrights (Bertolt Brecht, 1898–1956), historians of science (Thomas S. Kuhn, 1922–1996)67 and also Braudel. Today the fluid borders between visual craftsmanship, the tacit knowledge of engineers and precursors of 'experimental physics' are usually highlighted.68 The transformation of the Aristotelian method within the Padovan school (Logics), producing the double regress of combining induction and deduction tend to complexify our view today so much that it seems almost banal to search for a similar "central point or core".69 Certainly, we are talking about pre-Baconian forms of empiricism in its impact on scholastic teaching and systems on the one hand, on experimental investigations on the other, and the generation of laws or regularities. Some of the early Italian academies (in the 1560s) were already specializing on such forms instead of moral philosophical, ethical, courteous or esthetic discussion.70 But perhaps the Padovan transformation of the Aristotelian form of teaching (prior to and next to the still different Ramus effect) was until 1650 of greater impact as "Italian radiation" in processes of diffusion than the Galilei affair decades later. The nexus between the remaining Galilean forms of science in "Italy" and the Baconian Western forms of empiricism during the 1630s to 1650s (Ferdinando II de Medici's (1610–1670) Tuscan circles, then his academy, and the exchange with future founding members of the Royal Society)71 is a somewhat different and complex story of mutual transfers and less one that was considered and lived by its protagonists as a reception of "Italian Renaissance science".

For the other fields mentioned above, there is some legitimacy to keep the nexus between "Italy" and "Renaissance", as forms of transalpine diffusion that recalled and exposed semantically a special "Italian" style of politics, of merchant craftsmanship and techniques, of art. An indicator for that is how technical languages (Fachsprachen)72 and several key words were appropriated in that time throughout Europe, being used in the original or Latinized by Western and Northern authors: ragion di stato, bilancia di forze, neutralità, principe and so on in the realm of politics ;73 cambio, premio, assicuranza, banca rotta and so on in the realm of economics are to be found in French, English, German, Dutch, Spanish, and in all-European Latin forms since around the 1580s at latest

;73 cambio, premio, assicuranza, banca rotta and so on in the realm of economics are to be found in French, English, German, Dutch, Spanish, and in all-European Latin forms since around the 1580s at latest .74 Not to mention the practical work and handbooks of engineers, mathematicians, ballistic and fortification masters

.74 Not to mention the practical work and handbooks of engineers, mathematicians, ballistic and fortification masters , specialists in "military science" (arte della guerra): When Geoffrey Parker coined elements of that – the distribution of fortifications following the Italian style according to ballistic calculation transcending the old type of castle architecture – the trace italienne,75 he did not just ingeniously invent a historiographical term, but it was already recognized during the 16th century to be a specially Italian expertise in that field.

, specialists in "military science" (arte della guerra): When Geoffrey Parker coined elements of that – the distribution of fortifications following the Italian style according to ballistic calculation transcending the old type of castle architecture – the trace italienne,75 he did not just ingeniously invent a historiographical term, but it was already recognized during the 16th century to be a specially Italian expertise in that field.

The one level to answer the question why and how there was a dominant direction of cultural flows lies in rather accidental, external or exogenous causes, touched upon already by Braudel's time by Delio Cantimori (1904–1966) and his disciples: People moving are carriers of ideas, objects, artefacts; and as the wars of Italy (1494–1559) were setting a disproportionable mass of French, Spanish, German, and even Polish and other clients of the Habsburg dominions in motion towards Italy, as did also the wars against the Ottomans and their preparation in, with and through Italy, the chances of contact were increased. Since François Hotman (1524–1590) (Monitoriale adversus Italogalliam, 1575) to Jean-François Dubost this phenomenon was discussed under the header of "la France italienne"76 referring to Italian noble and literate immigration as a late product of the politico-dynastic entanglement of French and Italian interests during the first half of the 16th century. Likewise, the migration of individual Italians for religious reasons since the 1530s and for economic reasons since the 1610/20s are another important factor of increasing Italian contact zones.77 Many heterodox Italians were migrating towards the North, towards England, Netherlands, Germany, Poland.78 Often traveling without other products "to sell", their capital was their expertise, achievements, simply also their Italian books and texts which they translated and printed. Lyon, Strasbourg, Basel, and also Antwerp, London, Vienna, Heidelberg, even small towns like Hanau, and to some extent Cracow, became important centers of diffusing the Italian Renaissance outside Italy, sometimes now in synchrony with the migrations caused by the Western Wars of Religion. The "Italian Renaissance" became therefore merged and adapted not only to the local contexts and markets, but also assimilated and synchronized with French and Dutch references at the same moment.

The question on another level is how we can identify epistemic and communication conditions that were somehow congruent with the Italian ones, and which created a context of perceiving and representing the world in such a manner that the "epistemic cores" were acceptable and matching. The key should lie here first again in the transfer of the infrastructural conditions and the techniques of scripturality themselves. It is important to follow the diffusion of the technique of newsletter writing, and – in some regions of Europe later, in others earlier – of the diffusion of the inter-territorial and inter-state ambassadorial and agent system across Europe. These processes were more or less simultaneous with the diffusion and expansion of the postal relay system and its related forms of communication networks: it facilitated a perception of the whole European political reality in a similar form with the smaller Italian one. Still, this was different, as it had to compete and be arranged with persisting older forms and different feudal structures of governance and exchange. Roughly speaking, the emergence of a "European state system" after 1559 is to some extent the transfer of a form of perception that originated in Italy and was linked to a special form of communication. The semantic expressions – now: balance of powers instead of bilancia di forze, raison d'état instead of ragione di stato – linked to it are reactions to perceptions of the world in this new form created by inter-state and news communication. Similar holds true again for the diffusion of Italian merchant communication and its effects on its perception. Antwerp and Ghent refugees from the Dutch wars of religion were teaching now in French the basic forms of the Italian double-entry book-keeping system and the terminology of that merchant culture (banqueroute, banca rotta) in Cologne, a city still belonging to the old Hansa: during the 14th and 15th century the trade network of the North Sea and the Hansa had remained separated from the Mediterranean World.79

Conclusion

Using a narrative and concept such as that of the Model does not come without some necessary semantic "mortgages," due to its earlier uses and traditions. The title Modèle italien is itself perhaps a late development. However, the concept behind that word "modèle" is deeply rooted in Braudel's own thought since the 1940s and has roots even further back in inter-war discussions about civilizations, their history, their moments of greatest cultural elevation and how they were models for others, being observed and emulated. One has therefore to distinguish between the brilliant intuitions of Braudel and that what might seem today too biased by metaphysical concepts of ontologized actors in History like states and nations and teleological ideas about the structure of History's process as such. This is why I propose to adopt a rather narrow concept of "model" and to choose rather small synchronic complexes than large and transepochal ones. The sketch of what might be the Italian Renaissance's "core(s)" and why and how it spread through Europe, stimulating processes of cultural transfer and appropriation, could and should be more subtle, more extended, exemplified, challenged and tested concerning other fields and dimensions. Yet, in the end, this would be the place for resuming hundreds of years of research on the relationship between Italy and the rest of Europe during that period, on the Italian Renaissance as such – as Braudel put it, "Tout le ciel d'Europe en a été eclairé".80

Cornel Zwierlein81

Appendix

Literature

Aguirre Rojas, Carlos Antonio: Fernand Braudel und die modernen Sozialwissenschaften, Leipzig 1999.

Albrecht, Jörn et al. (eds.): Fachsprache und Terminologie in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Tübingen 1992.

Antal, Frederick: Florentine Painting and its Social Background: The Bourgeois Republic before Cosimo de' Medici's Advent to Power: XIV and early XV Centuries, London 1948.

Arlinghaus, Franz-Josef: Zwischen Notiz und Bilanz: Zur Eigendynamik des Schriftgebrauchs in der kaufmännischen Buchführung am Beispiel der Datini/di Berto-Handelsgesellschaft in Avignon (1367–73), Frankfurt am Main 2000.

Arnaldi, Girolamo: Fernand Braudel: riflessioni retrospettive di un medievista italiano, in: La Cultura 47,1 (2009), pp. 113–123.

Assmann, Jan: Das kulturelle Gedächtnis: Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen, Munich 1992.

Bahier-Porte, Christelle et al. (eds.): Écrire et penser en Moderne (1687–1750), Paris 2015.

Balsamo, Jean: L'amorevolezza verso le cose Italiche: le livre italien à Paris au XVIe siècle, Geneva 2015.

Balsamo, Jean (ed.): Passer les monts: Français en Italie, l'Italie en France (1494–1525), Paris 1998.

Baron, Hans: Renaissance in Italien, in: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 21 (1931), pp. 95–128 (Teil I), pp. 215–239 (Teil II), pp. 340–356 (Teil III).

Baron, Hans: Das Erwachen des historischen Denkens im Humanismus des Quattrocento, in: Historische Zeitschrift 147 (1933), pp. 5–20.

Bazzoli, Maurizio: L'equilibrio di potenza nell'età moderna dal Cinquecento al Congresso di Vienna, Milan 1998.

Bataillon, Marcel: Érasme et l'Espagne: recherches sur l'histoire spirituelle du XVIe siècle, ed. by Jean-Claude Margolin, Geneva 1998, vol. 3.

Baumann, Klaus-Dieter et al. (eds.): Kontrastive Fachsprachenforschung, Tübingen 1992.

Behringer, Wolfgang: Im Zeichen des Merkur: Reichspost und Kommunikationsrevolution in der Frühen Neuzeit, Göttingen 2003.

Bély, Lucien (ed.): L'invention de la diplomatie: Moyen Âge – Temps modernes, Paris 1998.

Beretta, Marco et al. (eds.): The Accademia del Cimento and its European Context, Sagamore Beach 2009.

Berger, Joachim / Willenberg, Jennifer / Landes, Lisa: EGO | European History Online: A Transcultural History of Europe on the Internet, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2010-12-03, online: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/introduction-2010-en [31/10/2018].

Bernhard, Patrick: Italien auf dem Teller: Zur Geschichte der italienischen Küche und Gastronomie in Deutschland 1900–2000, in: Gustavo Corni (ed.): Italiener in Deutschland im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Berlin 2012, pp. 217–236.

Besold, Christoph: Discursus politicus de incrementis imperiorum, eorumque amplitudine procuranda ..., Strasbourg 1623.

Black, Christopher: The Italian Inquisition, New Haven et al. 2009.

Black, Robert: Education and Society in Florentine Tuscany: Teachers, Pupils and Schools, c. 1250–1500, Leiden et al. 2007.

Boer, Pim den et al. (eds.): Europäische Erinnerungsorte, Munich 2012, vol. 3.

Bolzoni, Lina: L'Accademia Veneziana: Splendore e decadenza di una utopia enciclopedica, in: Laetitia Boehm et al. (eds.): Università, accademie e società scientifiche in Italia e in Germania dal Seicento al Settecento, Bologna 1981, pp. 117–167.

Boschiero, Luciano: Experiment and Natural Philosophy in Seventeenth-Century Tuscany: The History of the Accademia del Cimento, Dordrecht 2007.

Brandi, Karl: Das Werden der Renaissance, in: Academia 5 (1906–1908), pp. 3–28.

Braudel, Fernand: Les ambitions de l'Histoire, ed. by Roselyne de Ayala et al, Paris 1997.

Braudel, Fernand: L'Italia fuori d'Italia: Due secoli e tre Italie, in: Ruggiero Romano et al. (eds.): Storia d'Italia, Turin 1974, vol. 2: Dalla caduta dell'Impero romano al secolo XVIII, pp. 2089–2248.

Braudel, Fernand: La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l'époque de Philippe II, 9th edition, Paris 1990, vol. 1–3.

Braudel, Fernand: Le modèle italien, Paris 1994.

Braudel, Fernand: Ma formation d'historien, in: Braudel, Fernand: Les ambitions de l'histoire, ed. Roselyne de Ayala et al., préface by Maurice Aymard, Paris 1997, pp. 9–29.

Braun, Emily: Renaissance and Renascences: The Rebirth of Italy, 1911–1921, in: Gianni Mattioli et al. (eds.): Masterpieces From the Gianni Mattioli Collection, New York 1997, pp. 21–48.

Brunhes, Alain: Fernand Braudel: Synthèse et liberté, Paris 2001.

Buck, August: Einleitung, in: August Buck (ed.): Renaissance und Barock, Frankfurt am Main 1972, vol. 1, S. 1–27.

Bullard, Melissa Meriam: Lorenzo il Magnifico: Image and anxiety, politics and finance, Florence 1994.

Burns, Robert Ignatius: The Paper Revolution in Europe: Crusader Valencia's Paper Industry, in: Pacific Historical Review 50 (1981), pp. 1–30.

Cantimori, Delio: Eretici italiani del Cinquecento e altri scritti, ed. by Adriano Prosperi, Turin 1992.

Ceccarelli, Giovanni: Coping With Unknown Risks in Renaissance Forence: Insurers, Friars and Abacus Teachers, in: Cornel Zwierlein (ed.): The Dark Side of Knowledge: Histories of Ignorance: 1400–1800, Boston et al. 2016, pp. 117–138.

Charle, Christophe et al. (eds.): Transkulturalität nationaler Räume in Europa (18. bis 19. Jahrhundert): Übersetzungen, Kulturtransfer und Vermittlungsinstanzen, Göttingen 2017.

Chastel, André: La Crise de la Renaissance: 1520–1600, Paris 1968.

Chastel, André: Le Mythe de la Renaissance: 1420–1520, Geneva 1969.

Cooper, Richard: Litterae in tempore belli: Études sur les relations littéraires italo-françaises pendant les guerres d'Italie, Geneva 1997.

Crosby, Alfred W.: The Measure of Reality: Quantification and Western Society: 1250–1600, Cambridge 1997.

Dakhlia, Jocelyne et al. (eds.): Les musulmans dans l'histoire de l'Europe, Paris 2013, vol. 2: Passages et contacts en Méditerranée.

Damisch, Hubert: L'origine de la perspective, Paris 1987.

Desan, Philippe: L'imaginaire économique de la Renaissance, Fasano 2002.

Diplomazia edita: Le edizioni delle corrispondenze diplomatiche quattrocentesche (Bullettino dell'Istituto Storico Italiano e Archivio Muratoriano 110/2 [2008] 1–143).

Dooley, Brendan: The Dissemination of News and the Emergence of Contemporaneity in Early Modern Europe, Aldershot 2010.

Dreitzel, Horst: Von Melanchthon zu Pufendorf: Typen philosophischer Ethik im protestantischen Deutschland zwischen Reformation und Aufklärung, in: Martin Mulsow (ed.): Spätrenaissance-Philosophie in Deutschland 1570–1650: Entwürfe zwischen Humanismus und Konfessionalisierung, okkulten Traditionen und Schulmetaphysik, Tübingen 2009, pp. 321–398.

Dubost, Jean-François: La France italienne: XVIe–XVIIe siècle, Paris 1997.

Duchhardt, Heinz: Handbuch der Geschichte der Internationalen Beziehungen, Paderborn 1997–2012, vol. 1–9.

Eamon, William / Patheau, Françoise: The Accademia segreta of Girolamo Ruscelli: A Sixteenth-Century Italian Scientific Society, in: Isis 75 (1984), pp. 327–342.

Erll, Astrid: Kollektives Gedächtnis und Erinnerungskulturen: Eine Einführung, Stuttgart 2005.

Espagne, Michel / Werner, Michael: Deutsch-französischer Kulturtransfer als Forschungsgegenstand: Eine Problemskizze, in: Michel Espagne et al. (eds.): Transferts: Les Relations interculturelles dans l'Espace franco-allemand (XVIIIe et XIXe siècle), Paris 1988, pp. 11–34.

Espagne, Michel / Werner, Michael: La construction d'une référence culturelle allemande en France: Génèse et Histoire (1750–1914), in: Annales E.S.C. 42 (1987), pp. 969–992.

Espagne, Michel: Les transferts culturels franco-allemands, Paris 1999.

Evans, Arthur R.: Leonardo Olschki, 1885–1961, in: Romance Philology 31,1 (1977), pp. 17–54.

Febvre, Lucien: Le problème de l'incroyance au 16e siècle: La religion de Rabelais, Paris 1942.

Fehrenbach, Frank: Licht und Wasser: Zur Dynamik naturphilosophischer Leitbilder im Werk Leonardo da Vincis, Tübingen 1997.

Feingold, Mordechai: Before Newton: The Life and Times of Isaac Barrow, Cambridge 1990.

Ferguson, W. K.: Humanist Views of the Renaissance, in: The American Historical Review 45 (1939), pp. 1–28.

Fichte, Johann Gottlieb: Gesamtausgabe, ed. by Reinhard Lauth et al. München 1995, vol. 9: Werke 1806–1807.

Frajese, Vittorio: Nascità dell'Indice: La censura ecclesiastica dal Rinascimento alla Contrariforma, Brescia 2008.

François, Étienne: Écrire une histoire des lieux de mémoire allemands: pourquoi? comment?, in: Marie-Elizabeth Ducreux (ed.): Enjeux de l'histoire en Europe Centrale, Paris 2002, pp. 251–264.

Freedman, Joseph S.: Philosophy and the Arts in Central Europe, 1500–1700: Teaching and Texts at European Schools and Universities During the High and Late Renaissance, Aldershot et al. 1999.

Frigo, Daniela: Politics and Diplomacy in Early Modern Italy: The Structure of Diplomatic Practice, 1450–1800, Cambridge 2000.

Fubini, Riccardo: Italia quattrocentesca: Politica e diplomazia nell'età di Lorenzo il Magnifico, Milan 1994.

Fubini, Riccardo: La figura politica dell'ambasciatore negli sviluppi dei regimi oligarchici quattrocenteschi, in: Sergio Bertelli (ed.): Forme e tecniche del potere nella città (secoli XIV–XVII), Perugia 1982, pp. 33–59.

Garner, Guillaume et al. (eds.): Aufbruch in die Weltwirtschaft: Braudel wiedergelesen, Leipzig 2012.

Gemelli, Giuliana: Fernand Braudel e l'Europa universale, Venice 1990.

Gentile, Emilio: The Myth of National Regeneration in Italy: From Modernist Avant-Garde to Fascism, in: Matthew Affron et al. (eds.): Fascist Vissions: Art and Ideology in France and Italy, Princeton 1997, pp. 25–45.

Godman, Peter: The Saint as Censor: Robert Bellarmine Between Inquisition and Index, Leiden et al. 2000.

Goetz, Walter: Mittelalter und Renaissance, in: Historische Zeitschrift 98 (1907), pp. 30–54.

Goetz, Walter: Renaissance und Antike, in: Historische Zeitschrift 113 (1914), pp. 237–259.

Grafton, Anthony: What was history? The Art of History in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge 2007.

Gramsci, Antonio: Note sul Machiavelli, sulla politica e sullo stato moderno, 4th edition, Turin 1955.

Greimas, Algirdas Julien: Sémantique structurale: Recherche de méthode, Paris 1986, pp. 172–191.

Greimas, Algirdas Julien: Les actants, les acteurs et les figures, in: Algirdas Julien Greimas: Du Sens, Paris 1983, vol. 2: Essays sémiotiques, pp. 49–66.

Hahn, Walther v.: Die Fachsprache der Textilindustrie im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, Düsseldorf 1971

Hayez, Jerôme (ed.): Le carteggio Datini et les correspondances pratiques des XIVe–XVIe siècles: Actes du rencontre d'Avignon, 23 et 24 février 2001, in: Mélanges de l'École française de Rome – Moyen Âge 117, 1 (2005), pp. 115–304.

Hillmann, Jörg: Maritimes Denken in der Geopolitik Karl Haushofers, in: Werner Rahn (ed.): Deutsche Marinen im Wandel: Vom Symbol nationaler Einheit zum Instrument internationaler Sicherheit, Munich 2005, pp. 305–29.

Hoffmann, Lothar et al. (eds.): Fachsprachen: Languages for Special Purposes: Ein Internationales Handbuch, Berlin 1998.

Houssaye Michienzi, Ingrid et al. (eds.): ENPrESa: Bibliographie indicative, online: https://salviati.hypotheses.org/orientation-bibliographique [31/10/2018].

Houssaye Michienzi, Ingrid: Datini, Majorque et le Maghreb (14e–15e siècles): Réseaux, espaces méditerranéens et stratégies marchandes, Leiden 2013.

Irving, Sean: Limiting democracy and framing the economy: Hayek, Schmitt and ordoliberalism, in: History of European Ideas 44,1 (2018), pp. 113–127.

Isnenghi, Mario (ed.): I luoghi della memoria [dell'Italia unita], Rome et al. 1996/97, vol. 1–4.

Jackson, Ben: At the Origins of Neo-Liberalism: The Free Economy and the Strong State, 1930–1947, in: The Historical Journal 53,1 (2010), pp. 129–151.

Joachimsen, Paul: Aus der Entwicklung des italienischen Humanismus, in: Historische Zeitschrift 121 (1920), pp. 189–233.

Kammerer, Elsa et al. (eds.): De lingua et linguis: Langues vernaculaires dans l'Europe de la Renaissance, Geneva 2015–2018, vol. 1–6.

Keller, Kathrin et al. (eds.): Die Fuggerzeitungen im Kontext: Zeitungssammlungen im Alten Reich und in Italien, Vienna 2015.

Kinser, Samuel: Annaliste Paradigm? The Geohistorical Structuralism of Fernand Braudel, in: Stuart Clark (ed.): The Annales School: Critical Assessments, London et al. 1999, vol. 3: Fernand Braudel, pp. 124–175.

Korinman, Michel: Quand l'Allemagne pensait le monde: grandeur et décadence d'une géopolitique, Paris 1990.

Lang, Heinrich: La pratica contabile come gestione del tempo e dello spazio: La rete transalpina tra i Salviati di Firenze e i Welser d'Augusta dal 1507 al 1555, in: Mélanges de l'École française de Rome – Italie et Méditerranée modernes et contemporaines 125,1 (2013), pp. 143–151.

Lasansky, D. Medina: The Renaissance Perfected: Architecture, Spectacle, and Tourism in Fascist Italy, University Park 2004.

Lavagnino, Emilio: Gli artisti italiani in Germania: I pittori e gl'incisori, Rome 1943 (L'opera del genio italiano all'estero 1,5).

Lemoine, Yves: Fernand Braudel: Espaces et temps de l'historien, Paris 2005.

Lemoine, Yves: Fernand Braudel: Ambition et inquiétude d'un historien, Paris 2010.

Lerat, Pierre: Les langues spécialisées, Paris 1995.

Lutz, Heinrich: Braudels La Méditerranée: Zur Problematik eines Modellanspruchs, in: Reinhart Koselleck et al. (eds.): Formen der Geschichtsschreibung, Munich 1982, pp. 320–52.

Machiavelli, Niccolò: Opere, ed. by Corrado Vivanti, Turin 1997, vol. 1: I primi scritti politici.

Mallett, Michael: Italian Renaissance Diplomacy, in: Diplomacy & Statecraft 12,1 (2001), pp. 61–70.

Marino, John A. (ed.): Early Modern History and the Social Sciences: Testing the Limits of Braudel's Mediterranean, Kirksville 2002.

Martin, Eliseo Serrano: Erasmo y España: 75 años de la obra de Marcel Bataillon (1937–2012), Zaragoza 2015.

Mattingly, Garrett: Renaissance Diplomacy, London 1955.

Maulde-La Clavière, René A.: La diplomatie au temps de Machiavel, Geneva 1970, vol. 1–3.

Maylender, Michele: Storia delle Accademie d'Italia, Bologna 1929–1930, vol 1–5.

Mayoral, Juan V.: Five Decades of Structure: A Retrospective View, in: Theoria: An International Journal for Theory, History, and Foundations of Science 27 (2012), pp. 261–280.

Meiering, Gregor: Genèse et mutations d'une mémoire collective: la Méditerranée allemande, in: Wolfgang Storch et al. (eds.): La Méditerranée allemande, transl. by J.-P. Morel, Paris 2000, pp. 39–85.

Meier-Rust, Kathrin: Alexander Rüstow: Geschichtsdeutung und liberales Engagement, Stuttgart 1993.

Melis, Federigo: Aspetti della vita economica medievale: Studi nell'Archivio Datini di Prato, Siena 1962.

Melis, Federigo (ed.): Documenti per la storia economica dei secoli XIII–XVI, Florence 1972.

Ménissier, Thierry: Machiavelli und die Empire-Theorie der Gegenwart, in: Cornel Zwierlein et al. (eds.): Machiavellismus in Deutschland: Chiffre von Kontingenz, Herrschaft und Empirismus in der Neuzeit, Munich 2010, pp. 303–323.

Miller, Peter (ed.): The Sea: Thalassography and Historiography, Ann Arbor 2013.

Ministero degli Affari Esteri (ed.): L'opera del genio italiano all'estero, Rome 1933–1958.

Möhring, Maren: Fremdes Essen: Die Geschichte der ausländischen Gastronomie in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Munich 2012.

Moog-Grünewald, Maria (ed.): Das Neue: Eine Denkfigur der Moderne, Heidelberg 2002.

Morselli, Raffaella: Fuori dalla Guerra: Emilio Lavagnino e la salvaguardia delle opere d'arte del Lazio, Milan 2010.

Mulsow, Martin (ed.): Spätrenaissance-Philosophie in Deutschland 1570–1650: Entwürfe zwischen Humanismus und Konfessionalisierung, okkulten Traditionen und Schulmetaphysik, Tübingen 2009.

Murphy, David T.: The Heroic Earth: The Flowering of Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany: 1924–1933, Ann Arbor 1992.

Mussolini, Benito: Preludio al Machiavelli: nel quarto Centenario di Niccolò Machiavelli, Milan 1924.

Natter, Wolfgang: Umstrittene Konzepte: Raum und Volk bei Karl Haushofer und in der 'Zeitschrift für Geopolitik', in: Matthias Middell (ed.): Historische West- und Ostforschung in Zentraleuropa zwischen dem Ersten und dem Zweiten Weltkrieg: Verflechtungen und Vergleich, Leipzig 2004, pp. 1–28.

Nigro, Giampiero: Mercanti in Maiorca: il carteggio datiniano dall'Isola (1387–1396), Florence 2003.

Nora, Pierre: L'ère de la commémoration, in: Pierre Nora (ed.): Les lieux de mémoire, Paris 1992, vol. 3, pp. 977–1012.

Oesterle, Günter (ed.): Erinnerung, Gedächtnis, Wissen: Studien zur kulturwissenschaftlichen Gedächtnisforschung, Göttingen 2005.

Olschki, Leonardo: L'Italia e il suo Genio, Milan 1953, vol. 1–2.

Parker, Geoffrey: The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500–1800, Cambridge 1988.

Philippi, Adolf: Der Begriff der Renaissance: Daten zu seiner Geschichte, Leipzig 1912.

Piaia, Gregorio (ed.): La presenza dell'aristotelismo padovano nella filosofia della prima modernità, Rome et al. 2002.

Pillinini, Giorgio: Il sistema degli stati italiani 1454–1494, Venice 1970.

Piterberg, Gabriel et al. (eds.): Braudel Revisited: The Mediterranean World, 1600–1800, Toronto 2010.

Plaisance, Michel: L'Académie et le prince: Culture et politique à Florence au temps de Côme Ier et de François de Médicis, Rome 2004.

Polelle, Mark: Raising Cartographic Consciousness: The Social and Foreign Policy Vision of Geopolitics in the Twentieth Century, Lanham 1999.

Popplow, Marcus: Die Rückkehr des Künstler-Ingenieurs: Tendenzen und Perspektiven der Forschung zu Leonardo da Vinci, in: NTM Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik und Medizin 16 (2008), pp. 133–144.

Prosperi, Adriano et al. (eds.): Dizionario storico dell'Inquisizione, Pisa 2010, vol. 1–5.

Prosperi, Adriano: Tribunali della coscienza: Inquisitori, confessori, missionari, 2nd edition, Turin 2009.

Quiroz, Gustavo et al. (eds.): Les unités discursives dans l'analyse sémiotique: la segmentation du discours, Berne et al. 1998.

Randall, John Herman: The School of Padua and the Emergence of Modern Science, Padua 1961.

Raphael, Lutz: Die Erben von Bloch und Febvre, Stuttgart 1994.

Rassem, Mohammed et al. (eds.): Statistik und Staatsbeschreibung in der Neuzeit, Paderborn 1990, pp. 1–38.

Ricœur, Paul: La mémoire, l'histoire, l'oubli, Paris 2000.

Romier, Lucien: Les origines politiques des guerres de religion, Paris 1913, vol. 1–2.

Rossi, Guido: Insurance in Elizabethan England: The London Code, Cambridge 2016.

Rudolph, Enno: Die Renaissance: Innovatio oder Renovatio?, in: Achatz von Müller et al. (eds.): Die Wahrnehmung des Neuen in Antike und Renaissance, Munich et al. 2004.