See also the article "Forced labour in European colonies" in the EHNE.

Introduction

For several centuries, Europe was a larger contributor to intercontinental migration than any other continent, whereas migrants from other continents rarely chose the "old continent" as a destination. From 1500 onwards, more than 65 million Europeans left their continent for other shores, nine tenths of them after 1800. In comparison, migration from other continents to Europe was extremely limited. Until the First World War, only a very small number of Amerindians, Africans and Asians came to Europe, which was mainly due to lack of money. Migrating to another continent was expensive and the few Asians, Africans or Amerindians that could afford it had no desire to move to Europe. Besides, they were held back by immigration restrictions, especially pertaining to migrants from the colonies.

For Europeans, money was less of a barrier, although intercontinental migration on a mass scale did not occur before 1850. However, in the various European settlements overseas, migrants with sufficient funds to pay for the passage and to set up a farm or an enterprise in the colony had a good chance of improving their income and life expectancy, at least in the non-tropical colonies. In addition, some countries in Europe developed legal instruments, so-called contracts of indenture, which allowed citizens without savings to migrate to other continents. Some employees of the large European shipping and trading firms or companies operating outside Europe never returned home, but preferred to stay overseas once their contract had ended.

These legal and financial migration aids were unavailable to non-Europeans. From time to time an Amerindian, African, or Asian diplomat might visit Europe on his own account, but most non-Europeans only came to Europe as slaves. In Southern Europe, the importing of slaves dates back to the Arab conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, whereas in North-western Europe, the arrival of non-European slaves was limited to those who accompanied their masters when visiting Europe. Both migration streams warrant a separate description. Slaves were not only acquired in Africa, but also in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. Hundreds of thousands of young men and women were captured by Tatar slave raiders in Russia, Poland, the Ukraine and the Baltic states from the 15th century on and successively taken to the Asian part of the Ottoman Empire. The total number of Eastern slaves who left Europe in this way in the period from 1468 to 1694 is estimated at around 1,750,000, whereas in the 19th century another 200,000 such slaves, now from the Caucasus, were sold to the Ottomans. Until the 1460s, significant numbers of these slaves also ended up as domestic slaves in Italian cities like Genoa, Venice and Florence via slave markets in Black Sea ports such as Kaffa [Feodossija] and Tana [Asow].1

The Immigration From Africa Into Southern Europe (1500–1800)

Initially, Europeans, like other ethnic groups, traded and employed their compatriots as slaves, although they gradually began to look for servants at the eastern fringes of the continent, as the name Slavs suggests. The European slave trade north of the Alps stagnated when the Roman Catholic Church insisted on the sanctimony of marriage (but not on the emancipation) of the slaves because then it became too expensive to keep slave families together. After 1200, the trade ended altogether.

South of the Alps, two slave supply systems remained intact. On the one hand, the Italian city states employed slaves from Eastern Europe both at home and in their overseas colonies along the Dalmatian coast and on the islands in the Mediterranean Sea. The demand for slaves increased in those areas where sugar cane was grown. Slowly but surely African slaves began to replace slaves from the East when the expansion of Turkey blocked the customary slave trade routes.

On the other hand, the slave trade connected with the Iberian Peninsula started to concentrate on African slaves once the Reconquista was over, because Muslim and Christian prisoners of war were no longer available. Hundreds of thousands (both men and women) were brought to Portugal, Spain, Sicily and – to a lesser extent – Northern Italy, where they worked as domestic slaves or craftsmen and in agriculture. In some cities, they made quite a demographic impact – in Lisbon, for example, around 10 per cent (10,000 people) of the population in 1550 were black slaves. Similar numbers are reported for Seville and Valencia. Estimates concerning the total African population range from 100,000 to one million, but we propose a more conservative educated guess of 300,000, half of whom came in the 16th century. Many of them or their children were released in the course of time and assimilated into Iberian and Italian society; some even married Europeans. A considerable number of Africans became active Christians or founded African brotherhoods. Generally, African slaves were treated with less cruelty than captive Muslims because their owners expected them to convert more easily to Catholicism.2

Other African slaves were forced to cultivate sugar cane in southern Spain and Portugal. Plantations with black slaves and white management became a model that was exported to the newly conquered islands in the Atlantic Ocean such as the Canaries, the Azores, Madeira and São Tomé. Soon, the system of gang slavery became de rigueur in Portuguese Brazil; from there it was exported to British, French, Dutch, and Danish America. Africa became the provider of most of the world's intercontinental migrants, the majority of whom were forcibly transported![Plan des Sklavenschiffes "Brookes" IMG "Stowage of the British slave ship Brookes under the regulated slave trade act of 1788", 1789, unbekannter Künstler; Bildquelle: Broadside collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (Portfolio 282-43 [Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-44000]; http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu/Slavery/details.php?categorynum=5&categoryName=Slave%20Ships%20and%20the%20Atlantic%20Crossing%20(Middle%20Passage)&theRecord=11&recordCount=78 auf www.slaveryimages.org, unterstützt von der Virginia Foundation for the Humanities und der University of Virginia Library.](./illustrationen/abolitionismus-bilderordner/plan-des-sklavenschiffes-brookes-1789-img/@@images/image/thumb)

African Slaves from the New World (1500–1800)

In addition to the immigration of African slaves into Spain and Portugal, a few Africans arrived in Europe via the New World, some of whom had been born in the Americas. These migrants were usually accompanying their master and kept their slave status while in Europe. London housed around 15,000 Africans in the middle of the 18th century. Compared to the number of Africans in the New World plantation areas, the number of Africans in Europe was small, but some played an important part in the abolitionist campaign to stamp out slavery wherever it existed. Jonathan Strong, a West Indian slave, ill-treated and abandoned by his master during their temporary stay in London, fought a successful legal battle against having to return to his master and thus to the West Indies, while James Somersett equally successfully refused to go to Virginia with his new master, who had acquired him at a slave auction in London. These legal cases stipulated that forced migration had no basis in British law. Similarly, Dutch and French laws did not recognize slavery, which made it risky for slave masters to travel to these countries with their slaves.

| Source: Emory University, Slave Trade Data Base. | ||||||

| Period | Number of Slaves | |||||

| 1514–1525 | 637 | |||||

| 1576–1600 | 266 | |||||

| 1601–1625 | 120 | |||||

| 1651–1675 | 3,582 | |||||

| 1676–1700 | 1,437 | |||||

| 1701–1725 | 182 | |||||

| 1726–1750 | 4,008 | |||||

| 1751–1775 | 1,151 | |||||

| 1776–1785 | 18 | |||||

| Total Sum | 11,401 | |||||

The 20th Century

After the importing of African slaves into Europe had ceased at the end of the 18th century, few non-Europeans migrants migrated to Europe. The 19th century is typically a century during which Europeans moved to other continents in greater numbers than ever before, whereas virtually no migration to Europe took place. There are a few exceptions, such as the migration of loyalists (including ex-slaves) to Britain in the wake of the American War of Independence; for similar reasons, some opponents of the new regimes in South America came to Europe. However, their numbers were small.

The volume of migration to Europe increased considerably during the 20th century due to five reasons:

- First of all, during the two World Wars large numbers of non-Europeans soldiers and temporary labourers worked for the Allies, including troops from French West Africa and British India, and indentured labourers from China.

- The second stimulus to migrate to Europe was decolonization. Millions of Europeans, ex-Europeans, and their local allies from French North Africa, the British colonies in southern Africa and South Asia, the Dutch East Indies, and Portuguese Africa moved to Europe right before, during and after decolonization because the states they were living in ceased to exist.

- The third stimulus was the rising demand for labour after the end of the Second World War. Britain started this process by allowing citizens from the Commonwealth to work on its territory, followed by France and other countries. In addition, many countries in Europe recruited labourers in African and Asian countries that had not been part of their former overseas empires.

- The fourth reason for intercontinental migrants to come to Europe was the quest for political asylum. Until then, political asylum had been requested by Europeans escaping from extremist regimes such as revolutionary France, communist Russia or Nazi Germany and Austria. During the Cold War, the few refugees who managed to leave the communist bloc received a warm welcome in West Europe. This tradition enabled a growing number of refugees threatened by extremist regimes, civil wars, and climate change in Africa, Asia, and Latin America to come to Europe.

- Finally, migrants also came to Europe for cultural and educational reasons, mainly Americans living in Paris, or African, Asian and South American students, as well as football players, mainly from Africa and South America. Each of these five migration streams into Europe will be highlighted separately.

Non-European Soldiers and Contract Labourers in Europe During the World Wars

In no other context were such devastating wars fought as in Europe during the 20th century. During the two World Wars, the main contenders were France, the United Kingdom and Russia (or the Soviet Union), i.e. the Allies, on one side and Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy (the Axis) on the other. In both wars, not only were the Allies supported by the Americans, but also by troops and labourers from their colonial empires and China. France had started this custom by recruiting North African troops during the Crimean War and the Franco-Prussian War. It continued to do so during the two World Wars as well as in the military occupation of the Rhineland during the interwar period, summoning troops from West Africa such as the tirailleurs sénégalais![Tirailleur sénégalais IMG [Yora Comba, 38 ans, St Louis, : ["Sénégalais", album de 41 phot. anthropologiques présenté à l'exposition universelle de 1889 à Paris. Des collections du prince R. Bonaparte. Enregistré en 1930], Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Société de Géographie, SGE SG WE-344, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7702327w.](./illustrationen/migration-from-the-colonies-bilderordner/tirailleur-senegalais-img/@@images/image/thumb)

In spite of the fact that during imperial times Britain had a large colonial army with large contingents of non-European soldiers, no group comparable to the Moluccan soldiers or the Harkis emerged in the former British colonies. Usually, the transfer of power during decolonization in the British Empire was peaceful, and no Asian or African soldier needed to fear for his life and those of his family in the newly independent states. However, around 8,000 South Asian soldiers, the Gurkhas

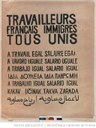

During the two World Wars, in addition to non-European soldiers, the Allies also employed non-European labourers behind the lines, mainly from India and China, ever since the Allied offensive in the Dardanelles during 1915, when Great Britain employed Egyptian labourers behind the lines. The French recruitment of Chinese labourers during World War I is a case in point. During this period, France felt an acute shortage of labourers in spite of the fact that more than 200,000 labourers from North Africa, Indochina![Annamites à Saint-Raphaël [soldats indochinois] 1916 IMG Annamites à Saint-Raphaël [soldats indochinois] 1916, BnF Gallica. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b69468188.](./illustrationen/migration-from-the-colonies-bilderordner/annamites-a-saint-raphael-soldats-indochinois-1916-img/@@images/image/thumb)

In total, Britain recruited about 100,000 Chinese and the French 40,000. Of these, 10,000 were passed on to the American army after the US entry into the war in 1917. Most of the Chinese came to Europe on a contract for 3 years, more than 90 per cent of them from northern China. Most of the Chinese contract labourers were employed in the war zones in northern France digging trenches and collecting the dead from the battlefield. More than 3,000 Chinese labourers were killed, and many suffered from infections such as flu and dysentery. After the end of World War I, Britain repatriated most of its Chinese contract labourers, whereas France allowed about 3,000 to stay, who mostly found work in industrial companies in or near Paris.6

During World War II, again sizeable numbers of non-European military personnel arrived in Europe. Soldiers from the Maghreb and Africa fought with the French troops in Germany, whereas the Russian armies included troops from the non-European parts of the Soviet Union. After the German capitulation, the Americans became the second largest group of Allied occupants. Many settled in Germany, but cannot be considered as immigrants since the American military only sent their personnel on a temporary basis. Special care was taken to separate the soldiers from the German civilian population by creating gated housing estates and army complexes in isolation from the surrounding towns and villages.7

Decolonisation and Migration

The decolonisation after World War II triggered a substantial migration to Europe. Some of the migrants returned to Europe soon after having left, but the great majority had never been to Europe, let alone lived there permanently. The largest groups came from French North Africa and Indochina (1.8 million), Portuguese Africa (about 1 million), and the Dutch East Indies (300,000); smaller numbers arrived from the former British and Belgian colonies in Africa and Asia.

All these migrants had a few main features in common. First of all, they usually left their countries of residence in a hurry. Given the tenacious war of independence in Algeria with many atrocities committed by both sides, the European population was afraid that their lives were in danger after independence, just like the population of European descent in Angola and Mozambique. Never in the history of migration had so many people moved to Portugal in such a short time: in 1975 almost half a million retornados arrived.8 The migration from the Dutch East Indies lasted longer: the first migrants came right after the Japanese defeat in 1945, whereas the last group came in 1963.

Most of these mass migrations were made more difficult by the lack of preparation in the host country. That was especially true of the Netherlands, where the infrastructure as well as a large number of houses had been destroyed or badly damaged during the German occupation. In addition, food was still rationed, and the amount of foreign currency limited. Both France and Portugal had more resources to house and feed the immigrants from their former colonies, but the large numbers made it difficult to provide work for everyone.

A third feature these migrations had in common was the mixed background of the migrants. In all cases, the number of Britons, Dutch, French, and Portuguese who had resided temporarily in the colonies was dwarfed by migrants who had not been born in the mother country. The first to arrive were the migrants from the Dutch East Indies. Between 1945 and the 1960s, about 330,000 immigrants of various ethnic backgrounds were shipped to the Netherlands. Besides the Moluccans, Dutch and other Europeans arrived who had resided temporarily in the Dutch East Indies and had wanted to return anyway after their release from Japanese internment during the war. They were the offspring of the European population in the Dutch East Indies, born in Asia, but culturally European. Also, 7,000 Chinese whose families had come from the Malayan Peninsula and 3,000 Christian Malayans moved to the Netherlands. Among the first group, many considered their stay in the Netherlands temporary, hoping to return to Indonesia after the fighting had abated. In fact, about a third returned. The majority of the migrants, however, remained hostile to the newly independent Indonesian Republic and its leaders.

The second group of about 150,000 migrants came to the Netherlands after Indonesia had gained its independence in 1949. Among these migrants, economic motives played a more important part. They realized that the Indonesian economy was not growing as fast as the Dutch. The forced nationalisation of European firms in Indonesia also triggered a wave of emigrants. The last batch of migrants mainly consisted of former Dutch citizens, 31,000 in total, who had first opted for Indonesian nationality, then realized that they had made the wrong decision and returned to the Netherlands in order to regain their Dutch nationality.

In the beginning, the integration of these migrants turned out to be difficult. During the German occupation, the housing sector in the Netherlands had suffered badly; the Dutch economy took some time to recover, and with 10 million inhabitants the Netherlands considered itself over-populated. That explains why about 10 per cent of the immigrants from Asia moved on again, about 30,000 to North America and about 9,000 to Australia. However, when the Dutch economy started to grow, the integration of the migrants from Indonesia became easier, because they spoke fluent Dutch and their education and work experience were accepted by Dutch employers. Apparently the first generation of these migrants integrated without any problem, and half of them married autochthonous Dutch partners. The second generation, however, felt different from mainstream Dutch society and started searching for their roots. At the moment, the number of Dutch who have their origins in the Dutch East Indies is estimated at 582,000, which represents about 3 per cent of the total Dutch population.9

Between 1954 and 1964, France received 1.8 million immigrants from its former colonies in North Africa and Indochina, of whom 1 million originated in Algeria. The latter group stood out, not only because of its size but also because of its social diversity. Algeria had been a settlement colony with large groups belonging to the lower strata of society and of mixed geographical origin. In addition to France, Algerian migrants had also moved to Spain, Italy, Malta, Switzerland, and Germany. They were called pieds noirs (black feet), probably because culturally they associated themselves with Europe, while their feet belonged to Africa.

Most pieds noirs settled in the South of France, although the government in Paris tried to distribute them all over the country. The immigrants were generally somewhat younger than the average age of the host society, and most of them came from Algerian cities, in spite of the persistent myth that the majority had been small farmers. In order to house the immigrants, many communities rapidly built whole new suburbs with flats and schools. The economic integration of the pieds noirs was not very problematic, as they arrived during the trente glorieuses,10 the 30 glorious years between 1946 and 1975, when the French economy grew rapidly. When the exodus from North Africa reached its peak in the years 1962 and 1963, more than 250,000 immigrants found employment. In many parts of southern France, the immigrants boosted the local economy and made innovations in the fishing industry in the Mediterranean ports or in agriculture by using new fertilizers and new machinery. And, last but not least, the French-speaking European colonial elite merged with the metropolitan elite in France without any problem. Some of the older generation among the pieds noirs might have felt that their migration to France was an exile; but the younger migrants realized that France offered them many more opportunities than would have been the case in independent Algeria, Tunisia or Morocco.11

The last mass migration after decolonisation took place in 1973 and 1974 when Portugal, after an internal revolution, decolonized its African and Atlantic colonies Mozambique, Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé and Principe. According to a population census of 1981, Portugal had received 471,427 immigrants from the former colonies by that year, 62 per cent of whom came from Angola, 34 per cent from Mozambique, and 4 per cent from the other ex-colonies in Africa. Never in the history of decolonisation did so many migrants leave in such a short time: only an airlift provided by Tap Air Portugal made it possible to move nearly a half million migrants within the period of 12 months. The massive influx of migrants caused the population of Portugal to increase by 6 per cent.

In many ways the label retornados for the migrants from Portuguese Africa was appropriate, since 63 per cent of the adult migrants had been born in Portugal and 40 per cent of those were aged under 18. Most of the immigrants settled in urbanized areas like Lisbon (32 per cent), Porto, and Setubal. As far as the level of education was concerned, the retornados had much more schooling than the population of the host country. Portugal was said to be the "poorhouse of Europe" – in 1974, 51 per cent of Portuguese adults had failed to complete elementary school, but only 17 per cent of the immigrants. Several government agencies provided financial aid to those immigrants who wanted to buy a house or start a business. The immigrants also organized themselves in associations for mutual support as well as to claim damages from the government. In many ways, the integration of the retornados in the Portuguese society was rapid and went smoothly, yet many first generation migrants felt some hostility from the European Portuguese, who considered the immigrants from Africa an alien element in their country.12

In addition to the above mentioned groups, many smaller groups can be identified in other colonies who also returned to Europe because of decolonisation. For many colonial civil servants and European army personnel in the British Empire and other parts of the French, Portuguese, and Dutch colonies, as well as for private businessmen and pensioners of European extraction, the disappearance of the colonial state was a reason to either move back to their country of origin or to another Western country. The same applies to those groups who collaborated closely with the European colonisers, such as the Chinese in Indonesia, the Gurkhas in India and the anti-communist middle classes in Vietnam.

Apart from these streams of migrants from the colonies to Europe, others migrated because the country they lived in had not yet been decolonized. This was the case in some former Dutch and French colonies in the Caribbean, the Mozambique Channel, and the Pacific which now have the status of an autonomous region, overseas department or overseas territory. In total more than 2 million French passport holders live in these areas, and about 200,000 Dutch. The reasons for moving to Europe were usually connected with the fact that the former colonial power offered better educational facilities, jobs, medical care and comprehensive pension schemes. In some ways, this type of migration can also be viewed as labour migration, but there was no real choice for the migrants. Besides, the migrants were not only looking for a job, but sometimes moved in order to be with their families or to benefit from the superior social security coverage and subsidized housing.

The fact that migration from the former colonies was not primarily aimed at filling the vacancies on the labour market of the host country, but could increase unemployment and housing shortages, made the British and Dutch governments decide to put an end to it. In 1962, the British government made a residence permit obligatory for those entering the country with a British passport. The Dutch government took a similar step in 1975 as part of a package granting independence to the former Caribbean colony of Suriname. The French, Portuguese, and Spanish governments also demanded residence permits from migrants coming from their former colonies after independence.

Non-European Labour Immigrants

The small number of non-European immigrants to Europe, such as soldiers from the US and the British Empire during the two World Wars, the African slaves, or the indentured labourers from India and China did not leave much of a mark as their stay was mainly brief. Even the American community in Paris between the wars was seen as temporary, and indeed this culturally influential group of writers, journalists, and beau monde virtually disappeared with the decline of the exchange rate of the US dollar during the Depression. Nevertheless, they contributed to the cultural transfer between French and American traditions by translating or discussing literary and artistic works and by creating institutions such as the famous American bookshop Shakespeare and Company

Some non-European labour immigration took place before 1945, but it was very limited in volume. Apart from the recruitment of Asian labourers during the First World War, about 3,000 "student workers" from China migrated to France in order to study at French schools or universities and to look for work. Most of the immigrants came from the urban lower middle classes in China and profited from the Chinese networks in France, originally set up for the incoming indentured workers recruited during World War I. In fact, one of their tasks in France was supposed to be the education of their often illiterate compatriots. Upon their return to China, many of these student workers were to join the Communist Party and later take up important positions in the People's Republic.

In view of the difficult economic situation in France and the political turmoil in republican China, it is not surprising that most of the migrants spent much more time working than they did studying. Furthermore, many migrants simply lacked the necessary schooling to become university students in France. That explains why most Chinese student workers lived near the factories where they worked in poor, overpopulated social housing like other migrant workers. In spite of the fact that foreigners in France were not supposed to be politically active, the student workers organized several demonstrations against the representatives of the Chinese government in France and generally stayed in close contact with their country of origin. Only a few of them intended to stay in France. In 1921, many of the student workers became the founding fathers of the French branch of the Chinese Communist Party. Among these were Zhou Enlai (1898–1976)[

In addition, most European ports housed small communities of non-European sailors, such as the Kru community in Liverpool, which consisted of people from the British colony Sierra Leone. For the European ships trading on the African coast, the Kru had always acted as navigators, interpreters, and as rowers and owners of canoes ferrying trade goods and slaves between the European ships and the coast. Over time, they were hired as seamen on British ships, replacing European crew members who had died. Some eventually settled in British ports, especially Liverpool, where a community of several hundred Kru men existed around the 1950s, many of them married to British women.15

Great Britain After 1945

During the 1950s, the immigration of non-European labourers became more substantial, and the United Kingdom was the first country to tap labour resources from other continents. Between 1950 and 1960, the number of immigrants from Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean in Great Britain increased from 20,000 to 200,000. At first, the West Indians dominated the immigration from outside Europe, mostly settling in the larger urban areas of the British Isles and mainly working in low-income jobs in hospitals, public transport, the postal services, and education. These jobs may have paid very moderate salaries, but they provided a high degree of security and allowed for a regular stream of money orders sent to the relatives at home. The island of Montserrat is an extreme example: about 50 per cent of its inhabitants worked elsewhere, and the money sent home made up about a quarter of the island's income. The larger countries in the Caribbean showed lower rates of labour emigration: Jamaica 9.2 per cent, Barbados 8.1 per cent, Trinidad 1.2 per cent, and Guyana 1.3 per cent.16

The West Indians in Great Britain, however, were soon outnumbered by the South Asians. Since government restrictions on immigration were put in place in the middle of the 1960s, the rapid growth of the South Asian community was caused by the immigration of family members, and in part by the high birth rates, particularly among the Muslim immigrant communities. Most of the immigrants came from the Punjab, an area which was divided between India, Pakistan, and Sikkim. War, deportation, and flight were widespread in the years following partition and made people migrate overseas. Another 20 per cent originated in the coastal areas of Gujarat, and another 10 per cent came from Sylhet in Bangladesh. In addition, the Asian community also comprised Tamils from Sri Lanka as well as well-educated Indians.17

Quite a few migrants did not move directly to Britain because they had first moved to another commonwealth country. One of the most prominent examples of such two-step migrations were the South Asians from East Africa. Many had gone to Uganda and Kenya at the end of the 19th century as indentured labourers in railway construction

France After 1945

After World War II, migrant labour contributed significantly to the rapid growth of the economy during the trente glorieuses between 1946 and 1975. In 1975 there were about 3.4 million immigrants in France, 40 per cent of whom came from non-European countries, whereas immigration from other European countries was dominated by the Portuguese. In comparison, back in 1946 more than 80 per cent of immigrants had come from Spain, Italy and Poland, and less than 10 per cent from non-European countries. However, these percentages are deceptive, as they do not include immigrants from the Départements d'Outre-Mer (Guadeloupe, Martinique and Guyenne), who had French passports. Their migration to France was not recorded, as it constituted an internal migration not involving a border crossing. In 1975, more than 100,000 migrants from the Caribbean were living in metropolitan France. The French authorities considered the immigration from the overseas departments in the West Indies preferable to that from the Maghreb and tropical Africa.

In spite of this preference, North Africans constitute by far the largest group of non-European immigrants in France. Their preference for France among destination countries in Europe is linked to the colonial past. Between 1848 and 1962, Algeria had been part of France, and its inhabitants, including the majority of Berbers and Arabs, were granted French citizenship in 1947. Besides, Morocco and Tunisia were incorporated into the French colonial empire as protectorates.

Because of the traumatic and very violent decolonization of Algeria, France was the first country to experience an anti-Muslim backlash in both politics and society at large. This happened in spite of the fact that large numbers of migrants from Algeria had been French citizens even before moving to France. The integration of migrants from North Africa turned out to be difficult, because about 35 per cent of the male immigrants and around 45 per cent of the female immigrants had not attended any school, and unemployment rates among the immigrants were high. In addition, the housing situation in the French outer urban districts (banlieues) remained bad. When the immigrants first arrived, the lack of subsidized housing resulted in the creation of improvised, ramshackle slums (bidonvilles), while over time the new, hastily erected large-scale, high-rise apartment blocks seemed to increase social unrest

Germany After 1945

Traditionally Germany, the largest economy in Europe, hardly knew any immigration from outside Europe. Germany had owned only a short-lived set of colonies in Africa and the Pacific that never sent out large numbers of their inhabitants. Until the 1960s, most labour migrants in Germany came from Eastern Europe and were what was called "Volksdeutsche" or "Aussiedler". After qualified labour migrants from Turkey found employment in Germany in the early 1960s, an agreement on the recruitment of Turkish labour migrants was signed. This resulted in a massive migration to Germany until 1974, when the recruitment was suspended. However, in the following decades many more Turks found their way to Germany, either as family members or as illegal immigrants.20 It must be added that the mention of Turkey in the context of migration into European countries may seem questionable, since the debate as to whether Turkey is culturally and geographically a part of Europe and might eventually join the European Union is still ongoing.21

The Netherlands After 1945

Migration from outside Europe to the Netherlands after 1945 fell into two major categories. First, decolonization caused about 300,000 migrants to move from Indonesia to the Netherlands (as discussed above); about 200,000 arrived from Suriname and about 90,000 from the Dutch Antilles. The second category consists of what in Germany were called "guest workers", from Turkey (360,000), Morocco (315,000), and the Cape Verdean islands (about 100,000 in 1970). In total, the Netherlands are the home of about 1 million immigrants from non-European countries. Besides, the Netherlands, like other countries in Europe, became the (temporary) home of perhaps as many as 100,000 to 150,000 illegal labour immigrants, many of them from non-European countries.22

Southern Europe After 1945

After World War II, southern Europe was initially a source of immigrants because Italians, Spanish, and Portuguese migrant workers moved to Western Europe, in addition to which large numbers of migrants looked for a permanent new home in North America, South America, Southern Africa, Australia or New Zealand. In the early 1970s, however, the number of such migrants started to decline, and slowly but surely Italy, Spain, and Portugal became countries of immigration. In Italy, the first non-European immigrants were mainly employed in housekeeping. They came from the Philippines, South America, the Cape Verdean islands, and the former Italian colony of Eritrea. Migrant workers from Tunisia helped to harvest tomatoes.23

As in Italy, Spain also experienced an influx of immigrants after 1979. At the moment, about 10 per cent of the Spanish population consists of foreign nationals. Due to its geographical location, the largest immigrant group does not come from elsewhere in Europe, but from nearby, across the Strait of Gibraltar: about 750,000 migrants from Morocco have settled in Spain, marginally more than the number of immigrants from Romania.24 In addition, there are about half a million immigrants from Latin America (Ecuador, Columbia).

Refugees and Asylum Migrants

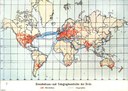

Refugees![Concentration of Refugees in Europe IMG United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (ed.), Concentration of Refugees in Europe [in the yeat 2000], source: UNHCR Statistical Online Population Database, www.unhcr.org/statistics/populationdatabase.](./illustrationen/migration-from-the-colonies-bilderordner/concentration-of-refugees-in-europe-img/@@images/image/thumb)

After the anti-Armenian policies of the Turkish government had led to genocide, with perhaps as many as 1.5 million Armenians being killed in the years from 1915 to 1917, Western Europe faced a large group of refugees from Armenia. Originally, more than 700,000 had fled to neighbouring countries, but later on 50,000 moved on to France, since that country already housed a small Armenian community. Many of these immigrants found jobs as craftsmen or in the textile and printing industries; a few of them were merchants or intellectuals. Some Armenians also joined the partisans fighting against the German occupation during the war. After 1945, their ongoing assimilation to the French way of life has become the subject of debates among many Armenians who fear the loss of their cultural identity.25

After the Second World War, the right to apply for asylum in Europe was put on a new footing by the 1951 Geneva Convention.26 At the time, the more liberal asylum rules only applied to those few who had been able to escape from the communist bloc. Slowly, but gradually the situation changed in the 1960s: First, refugees from the Middle East, mainly Iranians who opposed the regime of the Shah, saw themselves forced to move elsewhere, usually to France, Germany or the USA. After the regime of the Shah was toppled in 1979, another wave of emigrants left, this time those who opposed the orthodox Muslim policies of the new regime. Latin America also produced sizeable numbers of refugees after the military putsch in 1973.27

These are just examples of refugee movements to Europe after World War II. Many more groups

Conclusion

Looking at the numerous movements of migration from the European colonies to the countries governing them, we can observe a variety of cultural processes and alterations which did not only change and shape the individuals who left their homes in order to adapt to life in a foreign country, but also the foreign countries themselves. Migrants were not only victims of political or economic circumstances; they were also agents of cultural transfer who brought elements of their country's traditions to their new surroundings. One of the most prominent signs of their influence is the internationalization of European food culture in the 20th century. Nevertheless, it must also be remarked that non-European migrants' wishes to keep up their traditions have frequently been regarded with mistrust or even hostility in their host country.