General Trends in Development

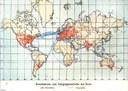

Trade played a more central role in the mercantilist period of European history from 1500 to 1750 – sometimes referred to as early capitalism or trade capitalism – than in almost any other period.1 We must begin with the questions: When in human history did the first exchange of goods between Europe and the other four continents of Africa, Asia, America and Australia occur? Where are the origins of what one could describe as on-going exchange, as established economic relations to be found? These questions refer to an even larger global context because the global economic edifice changed fundamentally from "proto-globalization" to globalization.2 This process was primarily determined by Europe from the 15th to the 20th century. From the 16th century to 1914, trade within Europe at all times constituted the most significant portion of global trade, and the volume of that trade grew disproportionately quickly during the early modern period and into the modern period.3 National markets became increasingly interconnected, driven by numerous innovations in the areas of infrastructure, transportation, energy supply, and – not least – institutions (rules, constitutions, division of labour, currency standards, etc.). The transition from individual production to mass production and the convergence of prices of goods and materials made transactions considerably easier, thereby accelerating integration.

Starting in the late Middle Ages at the latest and continuing at least into the 19th century, Europe dominated most developments in international trade. From the end of the 19th century, North America began to exert a stronger influence on the global economy.4 Around the beginning of the 21st century, the Asian states – most notably China – gained influence and the USA became financially dependent on its East Asian creditors, while China seems to become the engine of growth of the current century.

Europe Becomes Increasingly Central from the Late Middle Ages

In the early part of the last millennium, population movement and the cultivation of new territories increased as a result of the crusades and the eastward expansion of the German-speaking population. In 1500, there were five cities in Europe with populations greater than 100,000: Venice, Genoa, Naples, Milan, and – as the only example north of the Alps – Paris.

The reasons why Europe was able to gain a significant economic advantage over the other continents during the course of the early modern period are complex in nature. Initially, land – as the most important resource – played a central role, prompting landlords to engage in territorial expansion to gain ownership of more land. Additionally, the distribution of land was an effective method of ensuring the loyalty of vassals. In the archaic societies of central and Eastern Europe, where low population density meant that migration and innovation rarely became necessary, this form of land ownership persisted for a long time, surviving into the 19th century in some cases. In relatively densely populated regions – particularly in Western Europe, where land enclosure became increasingly common –, goods and knowledge were frequently exchanged, often across borders. The leading states of the European continent usually showed themselves to be open to innovations. This applied both to technological and commercial innovations, the latter primarily originating in Italy.5 The term "commercial revolution" is often used to describe this process.6

An argument often advanced to explain the unique position of Europe among the continents is the cultural and economic heterogeneity of its states. Migration and communication were the real accelerating factors of European history. The specific mix of (Italian) city states, principalities, bishoprics, kingdoms, etc., and the concomitant intensification of interregional competition accelerated development towards modernity. The "permanent incongruence" of economic, political and cultural factors explains the competitive dynamic of the continent.

The advanced system of education and the early institutionalization of centres of artisanal and early-industrial training and production also played their part. The liberalization of trade, craftsmanship and industrial labour, as well as the emergence of parliamentary democracy provided an essential basis for the generation of economic growth, which was accompanied from the 18th century by an impressive growth in population. The restless search for new knowledge which was a central feature of modern humanism and the enlightenment gave the Old Continent its unmistakeable appearance.

During the period of the ancien régime, the Netherlands had the most efficient and the most comprehensive network of roads of all the countries of Western Europe.7 From the late Middle Ages, increasing international trade made an international information

![Venetia 1572 IMG Frans Hogenberg (1535–1590), Venetia [Venice], in: Braun, Georg / Hogenberg, Franz / Novellanus, Simon: Beschreibung vnd Contrafactur der vornembster Stät der Welt, Köln 1582, vol. 1; digitized version, Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Persistente URL: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/braun1582bd1/0097.](./illustrationen/early-modern-ports-bilderordner/venetia-1572/@@images/image/thumb)

The "Oligopolization" of the Global Economy

In the period between the Industrial Revolution and the First World War, three powers were central in determining the rate of economic growth in Europe and Europe's relative importance in world events: Great Britain, Germany and France. In 1913, the last year in the first half of the 20th century which can be described as a "normal year", these three countries dominated large sections of the global economy. In this context, it is possible to speak of an "oligopolization" of the global economy, on which – along with the USA – these three states exerted the greatest influence. While these three countries contained less than half of the population of Europe, they accounted for approximately three quarters of Europe's industrial production and three quarters of all trade between Europe and the rest of the world. The high productivity levels of their economies were clearly reflected in the structure of their trade, i.e., in the exportation of industrial products and the importation of raw materials. As a result, these countries dominated the international flow of capital and direct foreign investment in the years before the First World War. In the absence of supranational economic institutions, Great Britain, which in London provided the central capital market of the world, in effect ensured that the global economy continued to function.10 Besides, the Bank of England followed the principle of the gold standard in all money and capital markets of the world and Great Britain generally adhered to liberal political principles. However, it proved impossible to resurrect this system after the First World War. After the global catastrophe of the Great Depression, global trade volumes declined by 26% and European trade by 38%.11

In the period between the Great Crash and the Second World War, national concepts replaced unified (foreign) economic and currency policies in Europe. In 1932, Britain forfeited its policy of free trade and gave precedence to the Commonwealth. Economic policy in the Third Reich followed Hjalmar Schacht's (1877–1970) Neuer Plan, with a series of discriminatory measures and a reorientation of foreign trade towards Eastern Europe and Latin America. France tried to improve matters by binding public and private capital together in so-called mixed companies in the key industries.12

The Second World War not only blocked the circulation of goods and capital within Europe, but it brought an end to the global economy for decades by splitting Europe into an eastern and a western part. Italy, Austria, the Federal Republic of Germany, France and the other democratic states committed themselves to liberal, free market economics and social democracy, while Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and East Germany adopted the centrally planned economy model of the Soviet Union, until this system was brought to an end by the people through a peaceful revolution after 45 years. Even before this, the view had gained acceptance that the innovation-oriented system of free market economics was superior to the more static concept of central planning and dictatorial management, and there had been signs of the approaching dissolution of the latter.

The reunified Germany and the "old" European axis powers were then able to agree new European economic, currency, and trade policies under the auspices of European supranational institutions such as the Council of Europe and the European Central Bank. Already in 1957, six western European states founded the European Economic Community (EEC). The establishment of a customs union in 1968 was a decisive step towards further integration. The European Union (EU), which had 12 members in 1986 and increased to 27 in 2011, developed into one of the strongest economic powers in the world beside the USA, Japan and China. With the European Central Bank and the Euro, the European Union established a uniform legal means of payment, which increasingly became a kind of reserve currency alongside the American dollar.

Phases of Different Intensity and Concentration in Growth and Trade

The expansion of European overseas trade did not occur in a linear fashion. Qualitatively and quantitatively, the 12th and 13th centuries, and the 16th and early 17th centuries were periods of strong commercial growth. Conversely, the 14th and 15th centuries, the second half of the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century must be viewed as phases of weaker or stagnating economic growth.13

The phases of pronounced expansion were usually accompanied by a strong increase in trade over land, primarily in a north-south direction (through the Champagne region in the Middle Ages, and through southern Germany in the second half of the 15th century and in the 16th century), but also in an east-west direction. In the 12th and 13th centuries, increasing sea-borne traffic in the Mediterranean provided a significant stimulus to transcontinental trade. Similarly, the phase of growth in transcontinental trade in the 16th century was accompanied by advances in Atlantic and intercontinental shipping. In the High Middle Ages, trade was also stimulated by the transportation of goods by caravan from regions in the Far East to Central Asia and finally to Eurasia. The southeastern European focal point of this trade was Venice, which – not coincidentally – was also the departure point of merchants such as the brothers Niccolò (1230–1300) and Maffeo Polo (1252–1309), and Niccolò's son Marco Polo (1254–1324)[

While European trade over land grew very slowly or stagnated in the late Middle Ages, trade between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea (Hanse), and between the ports of the North Sea (particularly Bruges) and the ports of northern and central Italy increased considerably. Growth was clearly driven by maritime expansion. Those who controlled the ocean had a position of hegemony in intercontinental mercantilist trade.15 From the 17th century, the trade in goods with regions outside of Europe grew as a result of the emergence of Dutch and British colonial trade. However, this could not fully compensate for the decrease in trade over land during the periods of weakness. In general, trade and economic development now occurred primarily in the central ports and their surrounding regions along the coasts of the European mainland.16 It is in this context that some speak of the "économie du pourtour", or the economy of the surrounding area, which refers to a particular economic region – for example, the Mediterranean – and its specific development.17

In the two periods of weak European growth, growth in maritime trade in the overseas regions was not particularly spectacular either. On the contrary, during the great depression in the 14th and 15th centuries, the conquests of the Turks and, in particular, the Mongol Tatars deprived European trade of access to important markets in the Levant. During the second period of weak economic growth in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, European overseas trade did not begin to expand significantly again until after the Portuguese-Spanish colonial empire had been replaced by the Dutch-British empire. This involved a certain shift of geographical focus, but it was essentially based on simple trade and exchange at garrisons and coastal bases, as well as plantation agriculture, which bore characteristics of slash-and-burn economics. In other words, colonial expansion also remained an économie du pourtour.

From the mid-18th century, both transcontinental and sea-borne trade experienced strong growth. The targeted expansion of European transportation and trade infrastructure, and the gradual acceptance of liberal economic thought, which replaced protectionist mercantilism, resulted in the dawn of a new period of economic development not only in Europe, but also overseas. The integration of the colonial interior, which was begun by Great Britain during the 18th century, assumed considerable importance in the early 19th century with the emergence of the idea of the frontier. Britain's "new colonial system" gradually transformed into a North American cotton-producing industry which accompanied and supported the emergence of early-industrial mechanization in Europe.18

European Trade During Industrialization

During the period of classical national economics, Adam Smith's (1723–1790)[

European industrialization lead to a rapid increase in demand for agricultural and industrial raw materials as well as for other goods, and it made the provision of quicker, cheaper and more efficient means of transportation and communication necessary

The First World War moved the axes of global trade. The international currency system disintegrated, and in 1914 countries such as Russia, Germany and France abandoned the convertibility of their currencies into gold. Since the most serious events of the war occurred on the European continent, they damaged structures of production and considerably harmed economic growth there. The high costs involved in converting factories from peacetime to war production, naval blockades, risk premiums, increasing inflation, and the rapidly rising cost of transactions due to the war damaged the European continent. As a result, the global economic order had undergone fundamental change to the advantage of America by 1918. Europe's portion of the world social product was declining.

The interwar years were defined by crises like no other period. Even in many European countries, currency and financial systems disintegrated. In particular, Weimar Germany was hit by a series of crises and political setbacks, for example the assassination of politicians such as Matthias Erzberger (1875–1921) and Walther Rathenau (1867–1922)[![Walther Rathenau (1867–1922) IMG Schwarz-weiß Photographie, o.J. [vor 1922], unbekannter Photograph; Bildquelle: Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection, DIGITAL ID: (digital file from original neg.) ggbain 20796 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.20796.](./illustrationen/europa-netzwerke-bilderordner/walther-rathenau-186720131922/@@images/image/thumb)

![Arbeitssuchender 1929 IMG Mann mit Schild "Nehme jede Arbeit an, da ich von keiner Seite unterstützt werde", Schwarz-weiß-Photographie, 1929/1933, unbekannter Photograph; Bildquelle: Deutsches Bundesarchiv, http://www.bild.bundesarchiv.de/cross-search/search/_1329901153/?search[view]=detail&search[focus]=1.](./illustrationen/globalisierung/arbeitssuchender-1929-img/@@images/image/thumb)

The dominance of protectionism and state intervention resulted in a kind of splintering of the global economy into systems and preference zones which were isolated from one another to a greater or lesser degree. Interwar Germany accessed energy resources and raw materials in eastern and southeastern Europe to strengthen its industry, but it neglected its consumer goods industry. In general, the interwar period in Europe was characterized by economic and social disintegration, and the "European house" had to be rebuilt from its foundations after the Second World War. This involved decreasing the amount of money in circulation, establishing monetary order, and making the European countries fit to re-join the global market. Thanks in large part to the Marshall Plan

With a 20% share of all global imports and exports, the European Union is the largest commercial power in the 21st century,27 followed by the USA, China and Japan. In 2010, goods to the value of 15,238 billion US dollars were exported worldwide (in 2009, it was 12,522 billion dollars). This equates to a growth of approximately 21.7% from 2009. The main exporters were the People's Republic of China, the USA, Germany, Japan and the Netherlands. These five countries together accounted for 35.9% of worldwide goods exports. In 2010, China was at the top of the list of the world's strongest exporting nations for the second time, followed by the USA and Germany.28

Europe and the African World

The discovery and conquest of Africa, America and East India in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period had long-lasting effects on the territories and regions involved. During the course of the 15th century, Portugal – centrally located at the connection between the two Atlantic zones – was able to conquer strategic locations along the west coast of Africa and in the African Atlantic region, though these bases suffered serious reversals between 1475 and 1480.29 In the 1440s, the Portuguese expanded their trade in African slaves in the coastal region of the Rio de Oro, which they were now able to conduct without the assistance of Asian and African middlemen. These strongly fortified settlements, such as those on the west African island of Arguim and in the town of Elmina in present-day Ghana, were not only centres of the slave trade, but also served as bases for the trade in gold, malagueta pepper, ivory and other trade goods.

Initially, it was Italian sailors and captains who, in the service of Portugal, explored the Atlantic islands off North Africa.30 In 1312, Lanzarotto Malocello (ca. 1270–1336), who came from the region around Genoa, discovered the Canary Islands. Lanzarote was named after him. In the early 15th century, the Portuguese secured further towns and islands in the region, for example Ceuta in 1415, Madeira in 1418, the Azores in 1427 and Cape Bojador on the African mainland. Subsequently, further bases along the west coast of Africa were added, progressing from north to south: Cabo Branco in 1441, Cape Verde in 1444, and the mouth of River Gambia in 1446. In 1456, the Italian Alvise Cadamosto (1432–1488), who was in the service of Henry the Navigator (1394–1460), claimed the Cape Verde Islands for Portugal.31 Sierra Leone was claimed in 1460, and Fort São Jorge da Mina was constructed two years later. Here, the Portuguese began to trade extensively, acquiring African gold in return for red and blue dyed cloth, head scarves, coral from Europe, brass armbands from Germany, and Portuguese white wine. In this trade as in the slave trade, yellow and red mussels from the Canaries were used as money.32

In the early modern period, Africa became the preferred region of operation of the privileged trading companies. England, France, the Netherlands, Switzerland and a number of other European countries delivered manufactured goods made of glass, metal and textiles, as well as weapons and alcohol to Africa in exchange for slaves, provisions, gold, etc. This European-African trade was often just one leg of the so-called triangular trade between Europe, Africa and America. This system of trade remained dominant from the 17th to the early 19th century, at which point the increasingly pervasive ban on slave trading shifted the focus of trade in Africa. Most of the African states became dependent on European colonial powers who reduced them to the status of suppliers of raw materials and comprehensively exploited them. Similar to South America, monocultures emerged in Africa which were heavily dependent on the weather conditions and the harvest cycle. Water shortages, famines, low per capita incomes and low literacy levels remain the consequences of African "modernity" up to the present. In many African states, the economic dominance of Western states persists up to the present, often referred to as neo-colonialism in the literature. The continuing demand for raw materials on the global market could greatly improve growth and the balance of trade in the resource-rich states of Africa if the resulting export surpluses were invested in the respective countries and found their way into the pockets of consumers there. In general, large differences in per capita incomes exist between the individual African states. The economic reality of Africa is too complex to be described solely in terms of dependency theories or the world system approach.33

Europe, the Orient and Asia

Leaving aside classical antiquity, territorial expansion from Europe towards Asia can be traced back to the period of the crusades, which lasted from the end of the 11th to the 13th century. Along the routes followed by the crusaders to southeastern Europe, across the Balkans and to the Levant, an impressive infrastructure emerged to meet the weaponry and provisioning needs of a few hundred thousand crusading knights and pilgrims bound for Jerusalem. Many of these provisioning stations were subsequently used by Italian and other European merchants for the transportation of goods to and from the Middle East and the Levant. Venice proved to be particularly well-placed geographically to benefit from this trade. It became the focal point for the exchange of goods and information between Asia and Europe,34 and a "model" for the subsequent trade networks of the colonial powers of Portugal, the Netherlands and Britain.35 The golden age of the lagoon city reached a climax after the conquest of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade (1199–1204). It is no coincidence that it was Venetian merchants like Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo who helped to establish the trade in goods with the Chinese Empire and even established diplomatic relations with the court of Kublai Khan (1215–1295). In doing so, they utilized existing routes such as the Silk Road, an important axis of medieval "global trade" which grew in importance in the late 13th and 14th centuries. This had a profound effect not only on the material culture of Europe, but also on Europeans' idea of Asia. In the Battle of Curzola in 1298, Marco Polo was taken into Genoese captivity, and he described his journey to the writer Rusticiano da Pisa while in prison. Through the writings of the latter, some details of Polo's experiences in China entered the mosaic of images, facts and beliefs which Europeans associated with China. In addition to members of the Polo family, other contemporaries also set out for Central Asia, such as the Flanders native Wilhelm von Rubruk (ca. 1210–1270) who set out in May 1253. Many were clergymen, such as the Franciscan Johannes von Montecorvino (1247–1328) who visited India and reported on spices such as pepper and cinnamon, and on the culinary habits of the Indians. Odorico da Pordenone (ca. 1286–1331) from Udine, who was also a Franciscan monk, travelled in 1314/1315 via Ceylon, Java, Singapore and southern China to Peking, and he reported on his experiences, both ordinary and extraordinary. More than 110 of his manuscripts have survived, and his influence has been significant.36

Whereas the Polos had travelled to Asia primarily by land, sea voyages to Asia increased from 1488 onward when Bartholomeu Diaz (ca. 1450–1500) from Portugal became the first to sail around the Cape of Good Hope. The establishment of the Portuguese empire in India made European-Asian relationships more permanent and secure. In some cases, Italian sea captains and southern German capital participated in these voyages.37 In the context of this double expansion in the Atlantic region and in the Far East, Lisbon became increasingly central and pivotal in global trade. It was no coincidence that many overseas expeditions by important explorers began in the Portuguese capital.

The first expeditions to Asia during and after the discovery of the sea route around the Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean witnessed conspicuous efforts on the part of southern, central and western European merchants and consortia to promote their interests in the east by means of agents. For example, wealthy Nuremberg and Augsburg merchants, and Dutchmen participated in the first voyages to India. Following the punctual pattern established in Africa, the Portuguese began to fortify ports and towns in strategically important places, in order to make them impervious to attacks. The cities of Calicut and Goa are examples on the Indian west coast. Development in the early modern period was dominated by the privileged trading companies of the Dutch and the British, but also of smaller states such as Denmark.38

From the 17th century, the Netherlands played a leading role in trade between Europe and the rest of the world, particularly trade with Asia. In the 18th century, Great Britain dominated the Asian markets, though its focus was on India instead of Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The British East India Company, founded in 1600, and the Dutch East India Company

In the 18th and 19th centuries, parts of Asia were increasingly drawn into the process of European industrialization. India in particular, as part of the Commonwealth, became an important source of raw materials (particularly cotton) as well as food and stimulants (particularly tea). The period of industrialization and of the rise of the middle class in Europe would not have been possible without these supplies and the intensification of exchange with Asia. The building of railways – a European innovation – began in the 19th century in Turkey, India, Japan and China, with lasting consequences for the territorialisation of economics and trade, and it provided the basis for further trade. The telegraph line between Calcutta and London, which was constructed by Siemens and opened in 1870, gave an important new stimulus to trade and the exchange of information between Europe and Asia. In all regions of Asia, enclaves and cities remained in European ownership until relatively recently, as in the case of Hong Kong which the British only relinquished in 1997.

America, the Pacific and Asia

If one defines interdependence as a regular, planned, systematic, on-going and reciprocal exchange of information and goods, then one can observe the beginning of American-Asian relations in 1519, at which time the Manila fleets began to sail regularly from Acapulco (Mexico) to Indonesia, or more specifically to the port city and trading centre of Manila on the Philippines. They brought precious metals, particularly silver, from Central America to Asia and usually transported spices, silks, porcelain and jewels back. Pearls from the islands of Cubagua and Margarita off the coast of Venezuela were also traded overseas. In the 16th century, this trade prompted southern German merchants such as Christoph Herwart (1464–1529) to get involved in trade with India.40

Europe Meets Australia in the 17th Century

It can be assumed that the discovery of the Cape York Peninsula by the Dutchman Willem Jansz (ca. 1570–1630) in 1606 was one of the first instances of economic contact between Europe and Australia. A decade later, Dirk Hartog (1580–1621) reached the west coast of Australia. During the course of the 17th century, Willem de Vlamingh (1640–1698) and William Dampier (1651–1715) "discovered" other parts of the Australian continent, thereby facilitating the more concentrated exploration and mapping of Australia. From a European perspective, Australia did not play a significant role in trade, though there was some British foreign investment in Australia before the First World War. This was focused primarily on the building and financing of infrastructure projects (railways, harbours, public buildings, etc.). Conversely, Australian wool and mutton were exported to Europe.41

Europe, the Atlantic and America

The beginning of relatively regular economic relations between Europe and America occurred in the 16th century. The initial contact with America which Vikings under Erik the Red (950–ca. 1005) established around 1000 BC cannot be described as a lasting exchange; neither can such exchange be said to have existed in the first two or three decades after America was rediscovered by the Genoese sailor Christopher Columbus (1451–1506).42

Trade between the Old World and the New World constantly experienced fluctuations which were caused by by economic growth and developments such as the discovery, mining and transportation of precious metals. This was true in particular of silver and gold from South America and Central America, and later from North America. The supply of coin metal to European states from overseas affected the currency stability, liquidity, monetary independence, and ultimately the profitability of early modern capital markets. However, due to insufficient domestic production, Spain was constantly dependent on imports from Asia, and a considerable portion of the precious metals imported from South America was transferred to Asia via Cádiz and Seville as payment. Consequently, the quantity of precious metals which was used to mint coins in Spain and Portugal should not be overestimated. The inflationary effect of imported precious metals was therefore less significant than has been assumed.43

Around the beginning of the 16th century, Portugal's double expansion continued with its turning westward and commencing to colonize Brazil. Impressive colonial cities came into being on the coast, such as Salvador do Bahia, the first capital city of Brazil. The eastern part of South America had been granted to the Portuguese by Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503) in the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494)

In the second third of the 16th century, transatlantic relations intensified, due in part to the discovery of precious metals in South America. During the course of the discovery of the American continent, not only did people of different ethnic backgrounds encounter one another, the material culture was also greatly enriched, for example by the arrival of previously unknown plants, animals and goods in Europe. Medieval Europe had no knowledge of cocoa and, consequently, of chocolate. Some present-day dietary staples such as maize and the potato, which – like tapioca and nasturtium – are good sources of carbohydrates, were previously unknown in Europe also. Equally new to Europeans were sugar-rich plants such as sugar maple and protein-rich legumes such as beans. Other plants such as peanuts provided oil and fat. New vegetable types such as tomatoes, peppers and pumpkins, and nuts and fruits from avocados and pineapples to guavas and papayas appeared on European tables. Europe became acquainted with intoxicants such as the products of the maté tree and the coca bush. Spices such as vanilla, allspice and chili contributed to the refinement of European culinary tastes. Tobacco was also cultivated in Europe for the first time in the early modern period. It is beyond question that the exchange of new types of food and stimulants has had an effect on patterns of behaviour – and even on architecture – in the modern period. Smoking rooms or gentlemen's rooms containing pipe stands, ashtrays, matches and similar utensils were a given in 18th-century and 19th-century villas. Coffee houses were often popular meeting places for artists and literati, and were consequently much-frequented places for meeting and communication which had a considerable effect on the culture of large European cities.

New types of wood, such as rare pine species and mahogany, appeared in the sitting rooms of affluent Europeans. Quebracho trees and various species of mangrove provided tannic acid. Rubber trees and sweet potato trees provided rubber, while the wax palm, the carnauba palm and the jojoba provided wax. The variety of dyes available was also increased by access to tropical plants, ranging from the brazil wood to the redwood, the logwood, the yellowwood, and indigo, which began to replace woad in Europe. The New World was also a source of numerous plants which provided insecticides, such as barbasco roots, the bitterwood, and the cashew nut; even tobacco falls into this category. Today "American" plants are even used as fuel sources, as experiments with tapioca, maize and species of copaiba demonstrate.45

Conversely, Europe enriched the American continent by the introduction of new animal and plant species, as well as new inventions, cultivation techniques and ideas. These ranged from horses, cattle, donkeys and hens to honeybees and silkworms, and from new types of cereals such as barley to apples, apricots, almonds, various types of cabbage, carrots, aubergines, flax and garlic. Europeans also introduced a vast array of weapons and craft tools, as well as institutional innovations such as Roman law, which was established in many states of North and South America. There were also innovations such as the amalgamation process for extracting silver and gold from ores using mercury, or book printing, which accelerated and intensified the transfer of information and knowledge from the Old World to the New World.

To summarize, the encounter between the material and intellectual cultures of Europe and America resulted in enormous mutual enrichment and inspiration.46 However, it also had negative effects, such as the transfer of diseases in both directions. Many more indigenous Americans died as a result of "European" diseases than died in violent confrontations during the course of the Conquista. Conversely, European travellers contracted "American" illnesses which had not existed in medieval Europe.

The Netherlands, England, France, and other European countries (Denmark, Sweden, Austria, Prussia, Switzerland, etc.) sought to gain access to trade in Asia, Africa and America by means of privileged companies. In the 17th and 18th centuries, this often took the form of the so-called triangular trade, i.e., participation in trade with Africa, America and the Caribbean, and the rest of Europe, African trade being largely synonymous with slave trading. Slaves were bought in exchange for European manufactured goods and subsequently transported to the large estates of the West Indies and America on special slave ships.47 In the early modern period, 10 to 12 million Africans were taken in this way to the New World, from where colonial produce was transported to Europe. Privileged European trading companies were also employed in Atlantic trade, such as the Royal African Company and the Hudson's Bay Company, the Dutch West India Company and corresponding French companies.

The expanding European settlements in America required a growing number of labourers for the work on plantations and other possessions. As a result, the triangular trade persisted until the abolition movement of the 19th century. Denmark and Great Britain abolished slavery in 1807, followed by the USA in 1808, and Holland and France in 1814. In addition to the role played by the American and French revolutions in promoting freedom and human rights, economic interests played a decisive role in this process. New economic systems which emerged as a result of the industrial revolutions began to replace old mercantilist forms. The emerging polypolistic variety of markets was accompanied by the intensification of market formation and of competition. An economic transformation occurred, which introduced new institutional forms, a liberal economic and social order, and a radical integration of world markets. Subsequently, global exports grew as a proportion of the world social product from approximately 1% in 1825 to approximately 8% in 1900, and finally to approximately 16% in 2000. The global economy has multiplied by 44 since 1820, and global trade has grown in volume by a factor of 600 in the same period.

Up to the First World War, Western Europe undoubtedly contributed most to the world gross social product. In 1913, it accounted for 906 billion international dollars (of a total of 1990 billion), which equates to 33.5% of the World Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 1950, this percentage declined to 26.3%, and by 1998 to 20.6%.48 While Europe's trade with territories in the rest of the world grew in absolute terms, it became less important in relative terms since trade relations between the industrialized countries grew disproportionately quickly in significance.