Materialities – What is a travelogue?

The relics of travel are usually referred to as travelogues or travel accounts. In a broader sense, they are part of the meta-genre "travel literature" or "travel writing" that also includes theoretical and practical literature, like travel guides or the ars apodemica – guidelines on how to travel and how to write a travel account.1 What constitutes a "travelogue" – in terms of content, materiality, authorship, and production context – has been defined very differently at different times, and continues to be a discussion of its own.2 All these definitions have one aspect in common: the content has to describe travels – usually referring to the movement of people in time and space – that have a starting point and lead the traveller via a variable set of further points outside of her or his familiar cultural environment.3 Some definitions only include travel relics by people who returned to their point of departure,4 others also include travellers who died while travelling, as well as sources on the beginnings of (forced) emigrations, which might also be considered as journeys.5

While many definitions exclude fictional travel accounts, referring to relics of voyages that were not actually undertaken,6 it is generally accepted that there is no binary distinction between fact and fiction. It is often difficult or impossible to establish the biographical background of the author due to a lack of sources, and the distinction between factuality and fictionality was not clear or important in all places and at all times during the (early) modern period. Like every form of communication, travelogues are a product of subjective and usually intended acts, which were often meant to entertain an audience or to represent the author(s). Every travelogue therefore includes a certain amount of fictionality,7 but apparent factuality was also created artificially,8 and fictional narratives influenced factual ones at times.9 The complexity of this distinction is illustrated by The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a travelogue that describes a journey to the Middle East . It circulated as a manuscript from the mid-14th century onwards, and is still available in print today. The supposed author, Jean de Mandeville or John Mandeville (1300–1372), may be a fictional character. The actual author(s) probably never travelled to the region, and the text and images are a compilation of previous travelogues and histories. But up to the 19th century, readers believed this travelogue to be factual and, because of its great popularity, for centuries it was far more influential than contemporary travel accounts that were factual.10 In view of the production context, one would have to categorize the book as a fictional account. But, taking its reception by contemporaries into account, it would have to be viewed as a factual report. Neither categorization seems satisfactory.

. It circulated as a manuscript from the mid-14th century onwards, and is still available in print today. The supposed author, Jean de Mandeville or John Mandeville (1300–1372), may be a fictional character. The actual author(s) probably never travelled to the region, and the text and images are a compilation of previous travelogues and histories. But up to the 19th century, readers believed this travelogue to be factual and, because of its great popularity, for centuries it was far more influential than contemporary travel accounts that were factual.10 In view of the production context, one would have to categorize the book as a fictional account. But, taking its reception by contemporaries into account, it would have to be viewed as a factual report. Neither categorization seems satisfactory.

As regards materiality, text has been defined as the only possible representational form of travelogues throughout most of history and according to most definitions. At a push, these definitions included pictorial "illustrations" of text.11 Recently it has been suggested that the definition should be extended to other forms of communication, and that travelogues can be handed down in various forms, be that through speech, non-verbal communication, text, image, or more recently video. According to this broader definition, oral narratives, (series of) images, or videos can also be considered travelogues if they reflect experiences during travels.12 However, European travelogues that have survived from the period 1450–1900 mainly consist of text and/or images. The texts themselves may be written in verse and/or prose, and they may be attributed to one or several genres – diaries, letters, memoirs, missives, or reports. From the mid-1550s onwards, some of the accounts were written in accordance with the ars apodemica, but these guidelines were usually only partially adhered to, if at all.13 Consequently, it is also hard to ascertain what contemporaries understood as travelogues, and how this changed throughout the modern period. At all times, however, different forms of itineraries – lists of stops along the route of a journey often including descriptions of each of these destinations – were a very common textual feature of travelogues, though itineraries were not always included, especially in the case of travelogues that focused on the scientific results of expeditions, which became increasingly popular from the 18th century onwards.

Up to 1439, when Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1400–1468) introduced printing with movable type in Europe, travelogues mainly circulated as manuscripts. From this point on, the new form of printing revolutionized European communication, including travelogues. It is likely that the first printed travel account was a posthumous publication of a text that was already circulating as a manuscript, specifically either Hans Schiltberger's (1380–1450) Reisebuch (Augsburg ca. 1477) on his captivity and experiences in the Ottoman empire,14 or Ludolphus de Suchen's (also known as Ludolf Sudheim) (around 1350) Iter ad Terram Sanctam / Weg zu dem Heiligen Grab (Augsburg about 1476) on his pilgrimage to the "Holy Land",15 or a version of Marco Polo's (1254–1324) Travels, the first print of which appeared in German under the title Buch des edlen Ritters und Landfahrers Marco Polo (in Nuremberg in 1477).16 Incunables, or books that were printed before 1500, were as rare, expensive to produce and valuable as manuscripts, but the production of books expanded rapidly from this point on, and the increasing number of travel accounts constituted a substantial portion of the expanding book market. As these travelogues were subject to the marketing strategies and commercial interests of the authors, compilers, printers, publishers, and artists that produced them, the book market also influenced their content, as people usually printed content they expected to sell. At the same time, people continued to produce travelogues in manuscript form, which in some cases circulated in similar ways to printed travelogues, though the latter tended to reach bigger audiences. Printed and manuscript travelogues often influenced each other.17 There were also rich traditions of travel accounts outside Europe, though for various reasons most of them continued to be produced and circulated in manuscript form long after the introduction of moveable type.18

The images in travelogues are mainly mimetic, meaning they imitate – and thereby interpret – flora, fauna, landscapes, maps, people, architecture, and other works of art.19 From early on, European travel accounts often consisted of text and images, including two of the earliest printed works mentioned above. Marco Polo's travelogue appeared with a frontispiece representing the author , and the first edition of Schiltberger's Reisebuch included several images of people and animals, for example, travellers on camels and horses

, and the first edition of Schiltberger's Reisebuch included several images of people and animals, for example, travellers on camels and horses .

.

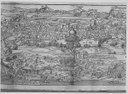

The first known travelogue that was specifically written and illustrated for print was Bernhard von Breydenbach's (1440–1497) Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam (first edition: Mainz, 1486). It included 28 illustrations by the artist Erhard Reuwich of Utrecht (1445–1505), among them maps of several important European and Middle Eastern cities like Venice and Jerusalem

and Jerusalem .20 Over the subsequent centuries, text and images remained strongly interconnected in travelogues, and new graphic technologies were quickly adapted, from copperplates and lithographs to daguerreotypes. Even the first book that included photographs was probably a travelogue: Maxime du Camp's (1822–1894) Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie: Dessins photographiques recueillis pendant les années 1849, 1850 et 1854 … (vol. 1–2, Paris 1852).21 The images

.20 Over the subsequent centuries, text and images remained strongly interconnected in travelogues, and new graphic technologies were quickly adapted, from copperplates and lithographs to daguerreotypes. Even the first book that included photographs was probably a travelogue: Maxime du Camp's (1822–1894) Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie: Dessins photographiques recueillis pendant les années 1849, 1850 et 1854 … (vol. 1–2, Paris 1852).21 The images arguably supported the travelogue's claim to authenticity, a claim that was further reinforced after the invention of daguerreotypes and photography.22

arguably supported the travelogue's claim to authenticity, a claim that was further reinforced after the invention of daguerreotypes and photography.22

In addition to text and images, the materiality of the accounts needs to be considered. As with other media, the number and quality of illustrations, the type and scope of the text, and the writing material imply to an extent the price, intended audiences and agenda of a travelogue. For example, short texts in vernacular languages on sketching paper without any adornment were less expensive than richly illustrated, voluminous books in Latin on higher-quality paper. The latter were only affordable and comprehensible to a small segment of society.23 The relevance of other material objects that were built for, or obtained by travellers must not be underestimated. These objects – such as ships, maps, scientific instruments, craftwork, or clothing – may offer additional information on journeys, the intentions of the travellers, and their destinations that is not contained in the travelogues themselves.24

The authorship and production context of travel accounts varied dramatically. The surviving travelogues from the early modern period were usually produced by the travellers themselves. Those in written format were usually composed in the first person. They are therefore "ego documents" or, in the narrower sense, "self-testimonies" (Selbstzeugnisse).25 Travelogues nonetheless heavily relied on each other. Text passages, images, and motifs continued to be reused, newly compiled, adapted, and translated into other languages or graphic technologies. Even paratextual elements and the materiality of the travelogues (e.g., the format, type and scope of the writing and graphic material) tended to be similar. These practices also influenced the content. They were similar all over Europe, were not limited exclusively to travelogues, and are often referred to by the terms intertextuality, interpictoriality, intermediality, or intermateriality. They went hand in hand with the intentions and (material) conditions of the people involved in the production of travelogues, and should not be erroneously associated with today's understanding of plagiarism.26 It has been suggested that, during the early modern period, such practices of repetition of content were linked to the epistemic idea of "imitation" and made it easier for a text or image to be accepted as authentic and reliable by its audience.27

These practices, in turn, blur the boundaries of "authentic authorship". Similar to fact and fiction, it is not possible to draw a clear distinction between original travel accounts and historiographic works that relied upon travelogues as their sources. New editions of the same work or translations, which often differed in content and/or length from the original, complicate the picture even further. Additionally, some travelogues were not written by the travellers themselves, but, for example, by someone hired to do so (employees or servants). Or they were edited by someone else (e.g., editions by individuals that the author met during the journey, or by someone related to the author, as well as later editions and posthumous publications). Travelogues usually appeared as independent monographs, but they were also published as part of larger works (e.g., autobiographies, histories, periodicals), or in the context of travel collections.28 The latter were quite common throughout the modern period, and brought together travel accounts of multiple voyages in one volume or a series, and were often meant to display the power of a specific country or region. The first known travel collection was either De Orbe Novo Decades (first complete edition: Compluti [=Alcalá de Henares] 1530) by Pietro Martire d'Anghiera (1457–1526) that included various Spanish expeditions to the Americas,29 or Paesi Nouamente retrouati. Et Nouo Mondo (first edition: Vicentia 1507) by Fracanzano da Montalboddo on travels to America, Africa, and Asia.30 While travel collections remain popular up to the present day, the most written about collections are the prominent collections from the 16th and 17th centuries that focused on voyages to regions outside of Europe, like Giovanni Battista Ramusio's (1485–1557) Navigationi et viaggi (vol. 1–3, first edition: Venice 1550–1559), Richard Hakluyt's (ca. 1552–1616) The Principall Navigations, or the many travel collection series of the De Bry family (1590–1634).31

Origins and destinations

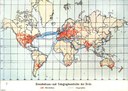

Up to the present day, scholars continue to gather more and more travel accounts from throughout the modern period. Apart from a few early attempts to compile comprehensive catalogues, particularly the Bibliothèque universelle des voyages by Gilles Boucher de La Richarderie (1733–1810), most bibliographies focus on travelogues written in, or dealing with, a specific geographical region or time period, or dealing with a specific subject. Other catalogues focus on travelogues held by a particular library and/or printed textual sources.32 These ever-expanding collections demonstrate the increasing popularity that travelogues enjoyed over the course of the modern period – from several hundred known travelogues in the 16th, to at least 1,500 in the 17th century, to more than 3,500 in the 18th, and several thousands in the 19th and 20th centuries.33 The languages that travelogues were written in were usually connected with the cultures of origin of the travellers or the lingua franca of their time. Translations enabled the wider dissemination of travelogues, but they make it difficult to assess the relative dominance of languages that reflects general political and sociocultural developments, as well as the power structures of the period. Latin, Italian and Spanish travelogues were the most common travelogues in the 16th century. In the 17th century, vernacular languages became dominant. French, and to a lesser extent German and Dutch, were the most prominent. From the 18th century onwards, French, German and – increasingly – English dominated the genre.34 However, much remains to be investigated about what connected and separated the travel reports in the different languages from a diachronic perspective.

Nevertheless, it is already well known that the travels described in the accounts from all parts of Europe and from the entire modern period had their origins in various undertakings, from short-term visits to lifelong ventures. The reasons why people left their familiar cultural environment were manifold, more often than not various reasons were intertwined. Most travels were linked to one or more of the following reasons: religion, economics, politics, education, health, tourism/leisure, and love. They included visits to festivities, markets, relatives or friends; religious pilgrimages and missions, professional undertakings by soldiers

and missions, professional undertakings by soldiers , merchants, artisans, diplomats, geographers, journalists, health workers, or spies, as well as educational voyages like those undertaken by artists, scholars, the nobility, and others. They related to mountaineering[

, merchants, artisans, diplomats, geographers, journalists, health workers, or spies, as well as educational voyages like those undertaken by artists, scholars, the nobility, and others. They related to mountaineering[ ] or leisure, or were undertaken with the intention of accessing health treatments, or to escape pandemics. Due to the heterogeneity of the topic, there are few tendencies that are common to travelogues in general, but at all times in the period 1450–1900 most European accounts described places in Europe, while the most popular destinations outside the continent shifted from the diachronic perspective as travelling and travel literature diversified. The accounts played an important role in the growth and circulation of knowledge about Europe and the world, and became more and more accessible to all sections of society.

] or leisure, or were undertaken with the intention of accessing health treatments, or to escape pandemics. Due to the heterogeneity of the topic, there are few tendencies that are common to travelogues in general, but at all times in the period 1450–1900 most European accounts described places in Europe, while the most popular destinations outside the continent shifted from the diachronic perspective as travelling and travel literature diversified. The accounts played an important role in the growth and circulation of knowledge about Europe and the world, and became more and more accessible to all sections of society.

From the second half of the 15th to the 16th century

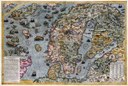

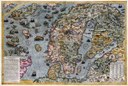

During the period ca. 1450–1600, most known travelogues were written by upper-class men like princes, nobles, diplomats, officers, scholars, merchants, the higher clergy, or their servants, and they describe places in Europe. Prominent examples are the Austrian diplomat Sigmund von Herberstein (1486–1566), who depicted his experiences during his voyage to Russia in his Rerum Moscoviticarum Comentarii (first edition: Vienna 1549), the archbishop of Uppsala Olaus Magnus (1490–1557), who apart from extensive travel writing also created the "Carta marina"[ ], one of the first maps of the Nordic countries (first edition: Venice 1549), and the Dutch officer Gerrit de Veer (ca. 1570–ca. 1598), who published his Diarium Nauticum on his experiences during his search for the Northeast Passage (first edition: Amsterdam 1598). Less well known are writers like Paul Pesel (around 1531), who recorded the journey of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500–1558) and his entourage from Augsburg to his coronation in Aachen, which included several other stops (Vienna 1531). From the late 16th century onwards, an increasing number of accounts were associated with the "grand tour[

], one of the first maps of the Nordic countries (first edition: Venice 1549), and the Dutch officer Gerrit de Veer (ca. 1570–ca. 1598), who published his Diarium Nauticum on his experiences during his search for the Northeast Passage (first edition: Amsterdam 1598). Less well known are writers like Paul Pesel (around 1531), who recorded the journey of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500–1558) and his entourage from Augsburg to his coronation in Aachen, which included several other stops (Vienna 1531). From the late 16th century onwards, an increasing number of accounts were associated with the "grand tour[ ]", a more or less obligatory voyage undertaken by young Europeans of sufficient means and rank, usually occurring after their coming of age, to visit other places in Europe, especially Italy and the Near East. This practice had existed since the Renaissance, but it flourished from this point onwards. A famous 16th-century example is Hercules prodicius

]", a more or less obligatory voyage undertaken by young Europeans of sufficient means and rank, usually occurring after their coming of age, to visit other places in Europe, especially Italy and the Near East. This practice had existed since the Renaissance, but it flourished from this point onwards. A famous 16th-century example is Hercules prodicius (first edition: Antwerp 1587), written by Stephanus Vinandus Pighius (1520–1604) describing the tour of his student Karl Friedrich of Jülich-Kleve-Berg (1555–1575), who died while travelling.35

(first edition: Antwerp 1587), written by Stephanus Vinandus Pighius (1520–1604) describing the tour of his student Karl Friedrich of Jülich-Kleve-Berg (1555–1575), who died while travelling.35

As regards places beyond Europe, most 15th and 16th century accounts were limited to the Ottoman empire. The importance of the Ottoman empire as a travel destination resulted from pilgrimages, wars, commerce and its proximity to Europe. It inspired, among many others, the accounts of diplomats in Habsburg service like Benedikt Kuripešič (born 1490), Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq (1522–1592), and Václav Vratislav z Mitrovic (1576–1635), the French soldier and geographer Nicolas de Nicolay (1517–1583), and the Spanish playwright, priest, and soldier Vasco Díaz Tleanco (died 1560). Voyages to other parts of the "old world" – referring to Africa and Asia – also resulted in several accounts, like those of the missionary Francisco Álvares (ca. 1465–1540) on Ethiopia, or those of the merchant Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563–1611) on Asia. Travelogues on the "new", and for Europeans less accessible world, especially the Americas, were relatively rare in numbers, but were of great interest, as the many re-prints and translations suggest. Prominent examples are accounts attributed to Amerigo Vespucci (1451–1512), those of the missionary Bartolomé de las Casas (1474–1566)[

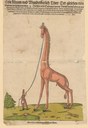

in Habsburg service like Benedikt Kuripešič (born 1490), Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq (1522–1592), and Václav Vratislav z Mitrovic (1576–1635), the French soldier and geographer Nicolas de Nicolay (1517–1583), and the Spanish playwright, priest, and soldier Vasco Díaz Tleanco (died 1560). Voyages to other parts of the "old world" – referring to Africa and Asia – also resulted in several accounts, like those of the missionary Francisco Álvares (ca. 1465–1540) on Ethiopia, or those of the merchant Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563–1611) on Asia. Travelogues on the "new", and for Europeans less accessible world, especially the Americas, were relatively rare in numbers, but were of great interest, as the many re-prints and translations suggest. Prominent examples are accounts attributed to Amerigo Vespucci (1451–1512), those of the missionary Bartolomé de las Casas (1474–1566)[ ], the scholar Girolamo Benzoni (1519–1570), the soldier Hans Staden (ca. 1525–ca. 1576), and Queen Elizabeth I's (1533–1603) favourite Walter Raleigh (ca. 1552–1618). Sections of travelogues of this time were adapted for popular prints which also reflects the great interest in the subject. A drawing of a giraffe by Melchior Lorck (or Lorichs, 1527–ca. 1590), for example, served as a template for a broadsheet in Nuremberg. The accompanying text emphasizes that Lorck had seen the animal with his own eyes in Constantinople

], the scholar Girolamo Benzoni (1519–1570), the soldier Hans Staden (ca. 1525–ca. 1576), and Queen Elizabeth I's (1533–1603) favourite Walter Raleigh (ca. 1552–1618). Sections of travelogues of this time were adapted for popular prints which also reflects the great interest in the subject. A drawing of a giraffe by Melchior Lorck (or Lorichs, 1527–ca. 1590), for example, served as a template for a broadsheet in Nuremberg. The accompanying text emphasizes that Lorck had seen the animal with his own eyes in Constantinople .

.

17th century

During this century, Europeans continued to write travelogues mainly about their own continent. The majority of the known sources are related to grand tours, and mostly concern Italy, especially those written by British "tour-ists" like Thomas Coryate (ca. 1577–1617) in Coryat's Crudities (first edition: 1611) or Richard Lassels' (ca. 1603–1668) The Voyage of Italy (first edition: Paris 1670). Other places – particularly Spain – featured prominently thanks to their pilgrimage sites, for example the three-volume Relation du voyage d'Espagne (first edition: Paris 1691) by Marie-Catherine d'Aulnoy (1650–1705). Other parts of Europe featured because they offered opportunities for exploration, such as Johannes Scheffer's (1621–1679) description of Lapland (Lapponia, first edition: Frankfurt am Main 1673) and Daniel Vetter's (1592–1669) description of Iceland (Islandia, first edition: Leszno 1638). The number of travelogues by people of lower social status started to grow, including, for example, a diary of the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) by the mercenary Peter Hagendorf (1601–1679) and an account of a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela (first edition: Vienna 1655) by the priest Christoph Gunzinger (1614–1673).

As for places outside Europe, geographical areas close to Europe, such as the Ottoman and Safavid empires, continued to be the focus of attention, for example in the accounts of Pietro della Valle (1586–1652), Adam Olearius (1599–1671), and Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605–1689). These regions also feature in the accounts of European Muslims on Hajj.36 Many of the travelogues on the Ottoman empire were related to military conflicts, often written by prisoners-of-war such as Bartolomej Georgijević (1506–1566). However, during the 17th century, travelogues on distant parts of the globe predominantly described sea voyages to Southeast and East Asia, Australia, Oceania, and India. These voyages were often undertaken or financed by merchants connected to the Dutch Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC, est. 1602) and the Geoctroyeerde West-Indische Compagnie (WIC, est. 1612, and reestablished in 1675). Prominent examples include the travelogues of Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck (1564–1638), Willem Corneliszoon Schouten (ca. 1580–1625) and Johann Sigmund Wurffbain (1613–1661) on the Pacific region, those of Edward Terry (1590–1660) and François Bernier (1620–1688) on India, the travelogues by Scipione Amati (born 1583) on Japan and by Nicolae Milescu (1636–1708) who travelled through Siberia to China. Such voyages were frequently accompanied by, or intended as, Christian missions, had a strong economic dimension, and were often heralds of imperialism. These "missions" were not always welcome. In Japan, for instance, the arrival of the first Portuguese ship in 1543, led to missionary activities by Dominicans, Jesuits and Franciscans and the conversion of many Japanese. In the first three decades of the 17th century, the Japanese authorities issued and enforced a series of edicts that not only banned Christian religions, but also travellers from Europe. Even Japanese travellers were forbidden (re)entry if their stay abroad had exceeded five years. At the same time, the kai-kin or "maritime prohibitions" brought overseas trade to a halt, with the exception of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC; Dutch East India Company), which operated from the artificial island Dejima. Japan only started to relax these provisions around 1800.37 During the 17th century, very few Europeans who were not associated with the VOC managed to enter Japan. One exception was the Italian Jesuit missionary Giovanni Battista Sidotti (1668–1715), who died during his imprisonment in Japan. His "travelogue" survived in the writings of the Japanese political thinker Arai Hakuseki (1657–1725), who interviewed Sidotti during his captivity.38

and the Geoctroyeerde West-Indische Compagnie (WIC, est. 1612, and reestablished in 1675). Prominent examples include the travelogues of Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck (1564–1638), Willem Corneliszoon Schouten (ca. 1580–1625) and Johann Sigmund Wurffbain (1613–1661) on the Pacific region, those of Edward Terry (1590–1660) and François Bernier (1620–1688) on India, the travelogues by Scipione Amati (born 1583) on Japan and by Nicolae Milescu (1636–1708) who travelled through Siberia to China. Such voyages were frequently accompanied by, or intended as, Christian missions, had a strong economic dimension, and were often heralds of imperialism. These "missions" were not always welcome. In Japan, for instance, the arrival of the first Portuguese ship in 1543, led to missionary activities by Dominicans, Jesuits and Franciscans and the conversion of many Japanese. In the first three decades of the 17th century, the Japanese authorities issued and enforced a series of edicts that not only banned Christian religions, but also travellers from Europe. Even Japanese travellers were forbidden (re)entry if their stay abroad had exceeded five years. At the same time, the kai-kin or "maritime prohibitions" brought overseas trade to a halt, with the exception of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC; Dutch East India Company), which operated from the artificial island Dejima. Japan only started to relax these provisions around 1800.37 During the 17th century, very few Europeans who were not associated with the VOC managed to enter Japan. One exception was the Italian Jesuit missionary Giovanni Battista Sidotti (1668–1715), who died during his imprisonment in Japan. His "travelogue" survived in the writings of the Japanese political thinker Arai Hakuseki (1657–1725), who interviewed Sidotti during his captivity.38

The Americas still featured prominently in the travel accounts of the 17th century. However, the geographical focus started to shift from the south to the north. For example, Friedrich Martens (1635–1699) described in his Spitzbergische oder Groenlandische Reise … (first edition: Hamburg 1675 ) his "discovery" of Spitzbergen, including several depictions of the animals and plants

and plants of the region. In the case of Africa, the west – especially the so-called "Gold Coast" on the Gulf of Guinea in today's Ghana – and the northeast of the continent (particularly Egypt and Ethiopia) were described most frequently, for example by Pieter de Marees (active 1600–1602) and Jerónimo Lobo (ca. 1595–1678).39 These travelogues – like those of the preceding and subsequent centuries – usually included maps and detailed descriptions of roads, tracks, and other pathways, which were intended to make travel easier for subsequent travellers. Such explorations were of fundamental importance for the growth of European geographical knowledge, which was often the main objective of the travels, which were in many cases financed by European authorities and princes. As David N. Livingstone (born 1953) put it, maps were always "a vehicle of conceptual and visual possession" and "geographical knowledge was geopolitical power".40

of the region. In the case of Africa, the west – especially the so-called "Gold Coast" on the Gulf of Guinea in today's Ghana – and the northeast of the continent (particularly Egypt and Ethiopia) were described most frequently, for example by Pieter de Marees (active 1600–1602) and Jerónimo Lobo (ca. 1595–1678).39 These travelogues – like those of the preceding and subsequent centuries – usually included maps and detailed descriptions of roads, tracks, and other pathways, which were intended to make travel easier for subsequent travellers. Such explorations were of fundamental importance for the growth of European geographical knowledge, which was often the main objective of the travels, which were in many cases financed by European authorities and princes. As David N. Livingstone (born 1953) put it, maps were always "a vehicle of conceptual and visual possession" and "geographical knowledge was geopolitical power".40

Many of the sea voyages of the century were also (re)published in the travel collections of the de Bry family (1590–1634) of Frankfurt. For publication in this series, the texts were usually translated and adapted, as well as richly illustrated with copperplates. The new texts and images did not always reflect the descriptions in the original accounts. These adaptations were most likely intended to popularize the content, and to appeal to the readership of the series.41 This tendency can also be observed in other (re)publications and travel collections,42 and may be linked to a general popularization of the genre that probably reflected a more positive attitude to curiosity.43

18th century

The 18th century was the heyday of the grand tour and Europe remained the focus of travelogues. Countless travel accounts can be found from the various levels of society almost all over Europe, but most travel writers came from Britain, France, the German-speaking lands, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia, and they wrote about Italy. Among them were Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689–1755), Thomas Gray (1716–1771) and Horace Walpole (1717–1797), Tobias George Smollett (1721–1771), Joseph Jérôme de Lalande (1732–1807), James Boswell (1740–1795), Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744–1803), and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832)[ ]. Others offered perspectives on western Europe, like Dositej Obradović (1739–1811) on England and France. Some offered perspectives on their countries of origin from exile, like Dimitrie Cantemir (1673–1723) writing in Russia about Moldavia.

]. Others offered perspectives on western Europe, like Dositej Obradović (1739–1811) on England and France. Some offered perspectives on their countries of origin from exile, like Dimitrie Cantemir (1673–1723) writing in Russia about Moldavia.

Asia – especially India and South East Asia – and North America were the most popular destinations described in European travelogues on places beyond Europe. Classic sea voyages like those of William Dampier (1652–1715), James Cook (1728–1779), or Louis-Antoine de Bougainville (1729–1811) maintained their important position, and the search for the Northwest Passage inspired travelogues such as Samuel Hearne's (1745–1792) A Journey from Prince of Wales' Fort in Hudson's Bay, to the Northern Ocean … (first edition: London 1795). Fictional travelogues became increasingly popular, and covered all sorts of real and imaginary destinations, among them Laurence Sterne's (1713–1768) A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy (first edition: London 1768), Eberhard Christian Kindermann's (born ca. 1715) Geschwinde Reise (first edition: s. l. 1744) on a voyage to a moon of the planet Mars, Jonathan Swift's (1667–1745) Gulliver's Travels (first edition: London 1726 ), and Daniel Defoe's (ca. 1661–1731) Robinson Crusoe (first edition: London 1719). The latter inspired a whole genre: the so-called "Robinsonade". While travelogues of the preceding centuries had usually focused on coastal regions of newly encountered places, travel accounts now increasingly described advancing into the interior of the continents, such as a journey from Egypt to Nubia (present-day Sudan) by Frederik Ludvig Norden (1708–1742), the search for the source of the Nile by James Bruce (1730–1794), the course of the river Niger by Mungo Park (1771–1806)[ ], or the first known east to west crossing of North America north of Mexico by Alexander Mackenzie (1764–1820). With the rise of romanticism and the aesthetic principles connected with it, landscapes and their picturesque depictions became the central theme of many accounts. Simultaneously, the interest in the collection and classification of flora and fauna increased. Inspired by his journeys through Lapland, Sweden and other parts of Europe, Carl von Linné (1707–1778)[

], or the first known east to west crossing of North America north of Mexico by Alexander Mackenzie (1764–1820). With the rise of romanticism and the aesthetic principles connected with it, landscapes and their picturesque depictions became the central theme of many accounts. Simultaneously, the interest in the collection and classification of flora and fauna increased. Inspired by his journeys through Lapland, Sweden and other parts of Europe, Carl von Linné (1707–1778)[ ] created one of the most influential botanical and zoological taxonomies. His work inspired other travellers, like Frederik Hasselquist (1722–1752) and Georg Forster (1754–1794)[

] created one of the most influential botanical and zoological taxonomies. His work inspired other travellers, like Frederik Hasselquist (1722–1752) and Georg Forster (1754–1794)[ ], who searched the globe and categorized animals and plants, and in some cases published their findings as travelogues. Like most travelogues on regions beyond Europe, such explorations had a strong colonial and commercial motivation. Most travellers not only exoticized the humans they encountered during their journeys, but also the flora and fauna, and cultural goods. It must not be forgotten that European "explorers" exploited, enslaved, kidnapped, and killed countless native people; imposed their laws, religious beliefs, and cultural practices on the latter; destroyed, burned or stole irreplaceable cultural heritage; and irreversibly changed ecosystems through the global export and import of flora, fauna, and diseases.44 However, new contact zones and the access to concepts, ideas, and cultures outside of Europe also strongly influenced the travellers, helping to shape what we perceive today as science.45

], who searched the globe and categorized animals and plants, and in some cases published their findings as travelogues. Like most travelogues on regions beyond Europe, such explorations had a strong colonial and commercial motivation. Most travellers not only exoticized the humans they encountered during their journeys, but also the flora and fauna, and cultural goods. It must not be forgotten that European "explorers" exploited, enslaved, kidnapped, and killed countless native people; imposed their laws, religious beliefs, and cultural practices on the latter; destroyed, burned or stole irreplaceable cultural heritage; and irreversibly changed ecosystems through the global export and import of flora, fauna, and diseases.44 However, new contact zones and the access to concepts, ideas, and cultures outside of Europe also strongly influenced the travellers, helping to shape what we perceive today as science.45

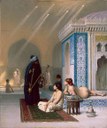

We know of almost no travelogues written before the 18th century that were written by women, even though they travelled almost everywhere men went, though usually as wives, daughters, or to work as prostitutes. From the mid-18th century onwards, this began to change. At first, women primarily wrote travel accounts in the form of letters, which circulated as manuscripts. Their accounts subsequently increasingly appeared in print too. Prominent examples are the accounts of Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762)[ ] and Elizabeth Craven (1750–1828) on Constantinople and the Crimea, which deconstructed male fantasies of the Ottoman harem. Friederike Riedesel's (1746–1808) Die Berufs-Reise nach America… (Berlin 1800) described the American Revolution. Ann Radcliffe's (1764–1823) Journey Made in the Summer of 1794 (first edition: Dublin 1795) took the reader through Europe.46 Some female travellers did not write travelogues themselves, but were instead featured and described by their fellow male travellers, like Jeanne Baret (1740–1807). As part of Bougainville's expedition, she was probably the first woman to complete a circumnavigation of the globe, though at first dressed as a man.47

] and Elizabeth Craven (1750–1828) on Constantinople and the Crimea, which deconstructed male fantasies of the Ottoman harem. Friederike Riedesel's (1746–1808) Die Berufs-Reise nach America… (Berlin 1800) described the American Revolution. Ann Radcliffe's (1764–1823) Journey Made in the Summer of 1794 (first edition: Dublin 1795) took the reader through Europe.46 Some female travellers did not write travelogues themselves, but were instead featured and described by their fellow male travellers, like Jeanne Baret (1740–1807). As part of Bougainville's expedition, she was probably the first woman to complete a circumnavigation of the globe, though at first dressed as a man.47

From the mid-18th century onwards, travelogues became increasingly accessible and enjoyed an even wider circulation thanks to newly emerging media. Periodicals such as La Gazette (1631–1915, from 1762 Gazette de France), Sammlung der besten und neuesten Reisebeschreibungen in einem ausführlichen Auszuge (Berlin 1763–1802), and Magazin von merkwürdigen neuen Reisebeschreibungen (Berlin 1790–1839, Vienna 1792–1804) in some cases specialized in travelogues, and frequently carried prepublications, new editions, and reviews of travel accounts. As a result, the accounts reached larger audiences than when published as a single travelogue.48 Circulating and subscription libraries also played a part in making even expensive travel literature accessible to the wider public.49 At the same time, travelling itself became affordable for more people, with rising numbers of tourists undertaking journeys for pleasure and recreation. In fact, the term "tourism" itself emerged in the 1780s in Britain.50

19th century

Many of the established tendencies intensified in the following decades, from increasing mobility, tourism, and advancing imperialism, to the increased mapping of the geography, flora and fauna of the world. Travellers had previously mainly travelled on foot, by horse or camel, or by sailing ship. In the 19th century, new means of transportation such as railways , bicycles, steamships, hot-air balloons, and motor cars were central to the idea of continuous progress and enabled an ever-growing number of people to travel and write about their experiences. Europe remained the most popular geographical area described in travelogues. While the "grand tour" had produced countless accounts, these now increasingly focused on the "home countries" of their authors. The British increasingly wrote about Great Britain, and the Germans about Germany, etc. From the mid-century onwards, the custom of the grand tour became less fashionable among the European upper-classes. This trend was accompanied by an increase in travel among other groups in society. This growing interest in tourism by the latter led, for example, to the establishment of publishing houses specializing in travel guides, like those of Karl Baedeker (1801–1859) and John Murray III (1808–1892). In 1841, the Thomas Cook (1808–1892) travel agency was established. The Orient Express made its first journey in 1883, and steam cruises and chartered trips catered for an increasing number of tourists from the upper middle classes. The destinations of pre-planned tours – Italy in particular, but also Greece, France, the Nile, Constantinople, and Jerusalem – were described in numerous guides. Critical voices spoke out against the 'herds' of tourists and their over-reliance on guidebooks, which probably fostered a more subjective style of writing in travelogues.51

, bicycles, steamships, hot-air balloons, and motor cars were central to the idea of continuous progress and enabled an ever-growing number of people to travel and write about their experiences. Europe remained the most popular geographical area described in travelogues. While the "grand tour" had produced countless accounts, these now increasingly focused on the "home countries" of their authors. The British increasingly wrote about Great Britain, and the Germans about Germany, etc. From the mid-century onwards, the custom of the grand tour became less fashionable among the European upper-classes. This trend was accompanied by an increase in travel among other groups in society. This growing interest in tourism by the latter led, for example, to the establishment of publishing houses specializing in travel guides, like those of Karl Baedeker (1801–1859) and John Murray III (1808–1892). In 1841, the Thomas Cook (1808–1892) travel agency was established. The Orient Express made its first journey in 1883, and steam cruises and chartered trips catered for an increasing number of tourists from the upper middle classes. The destinations of pre-planned tours – Italy in particular, but also Greece, France, the Nile, Constantinople, and Jerusalem – were described in numerous guides. Critical voices spoke out against the 'herds' of tourists and their over-reliance on guidebooks, which probably fostered a more subjective style of writing in travelogues.51

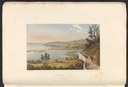

However, subjectivity also had its benefits, and many 19th century accounts were celebrated for their linguistic, narrative or pictorial qualities. While their authors differed vastly in terms of age, gender, class, and nationality, many – though not all of them – had already been renowned artists before the publication of their travelogues and are today associated with romanticism, like Madame de Staël (1766–1817)[ ], François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848), William Daniell (1769–1837), James Hakewill (1778–1843)[

], François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848), William Daniell (1769–1837), James Hakewill (1778–1843)[ ], Stendhal (Marie-Henri Beyle, 1783–1842), Hermann von Pückler-Muskau (1785–1871), Mary Shelley (1797–1851), Hector Berlioz (1803–1869), Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875), Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847), Charles Dickens (1812–1870), Theodor Fontane (1819–1898), and Dora d' Istria (1828–1888).52

], Stendhal (Marie-Henri Beyle, 1783–1842), Hermann von Pückler-Muskau (1785–1871), Mary Shelley (1797–1851), Hector Berlioz (1803–1869), Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875), Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847), Charles Dickens (1812–1870), Theodor Fontane (1819–1898), and Dora d' Istria (1828–1888).52

In general, the authors and their destinations became more diverse. More people of colour and people from less privileged sections of society composed travel accounts, like the businesswoman Mary Seacole (née Grant, 1805–1881)[ ], who in Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands (first edition: London 1857) wrote about her experiences during the Crimean War (1853–1856) and was the first black woman in Britain to publish an autobiography.53 Other travelogues focused on landscapes within Europe that were previously less frequently described. Mountaineering in the Alps, travel throughout the Balkans, Russia, and the eastern Mediterranean gained in popularity. Examples include Astolphe de Custine's (1790–1857) La Russie en 1839 (vol. 1–4, first edition: Paris 1843) about Russia, Alexander William Kinglake's (1809–1891), The invasion of the Crimea: Its Origin, and an Account of its Progress down to the Death of Lord Raglan (vol. 1–8, first edition: Edinburgh and London 1863–1887) on the Crimea, Archduke Ludwig Salvator of Austria's (1847–1915) Levkosia, die Hauptstadt von Cypern (first edition: Prague 1873) about Cyprus, and Leslie Stephen's (1832–1904) The Playground of Europe (first edition: London 1871) and Frederica Plunket's (1838–1886) Here and There Among the Alps (first edition: London 1875) both about mountaineering in the Alps.

], who in Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands (first edition: London 1857) wrote about her experiences during the Crimean War (1853–1856) and was the first black woman in Britain to publish an autobiography.53 Other travelogues focused on landscapes within Europe that were previously less frequently described. Mountaineering in the Alps, travel throughout the Balkans, Russia, and the eastern Mediterranean gained in popularity. Examples include Astolphe de Custine's (1790–1857) La Russie en 1839 (vol. 1–4, first edition: Paris 1843) about Russia, Alexander William Kinglake's (1809–1891), The invasion of the Crimea: Its Origin, and an Account of its Progress down to the Death of Lord Raglan (vol. 1–8, first edition: Edinburgh and London 1863–1887) on the Crimea, Archduke Ludwig Salvator of Austria's (1847–1915) Levkosia, die Hauptstadt von Cypern (first edition: Prague 1873) about Cyprus, and Leslie Stephen's (1832–1904) The Playground of Europe (first edition: London 1871) and Frederica Plunket's (1838–1886) Here and There Among the Alps (first edition: London 1875) both about mountaineering in the Alps.

Other travels within Europe inspired improvements in the authors' home countries. Count István Széchenyi (1791–1860), for example, planned to optimize Hungarian transportation after visiting Britain and the Ottoman Empire. Archduke Johann of Austria's (1782–1859) tour to England and Scotland probably informed his subsequent social and economic reforms, such as the foundation of the Steiermärkische Landwirtschaftsgesellschaft (Styrian Chamber of Agriculture) that spread new cultivation and harvesting methods, and the expansion of the railroad.54 Reformers like William Booth (1829–1912), who wrote about the plight of the English poor in his In Darkest England and the Way Out, shed light on social problems in their home countries, often describing the inhumane living conditions of workers, farmers, the sick, the poor, and other outsiders. In some cases, travel accounts in vernacular languages served nationalist and nation-forming agendas, especially in eastern Europe where linguae francae such as German, Latin or French were still commonly used. Travelogues like Constantin Golescu's (1777–1830) Însemnare a călătoriei mele, Constantin Radovici din Golești, făcută în anul 1824, 1825, 1826 (first edition: Bucharest 1826) about his trip to western Europe and his subsequent reforms in the school system helped to foster the expansion of vernacular languages, in this case Romanian.55 Fran Levstik's (1831–1887) Popotovanje iz Litije do Čateža (first edition: 1858) about his journey from Littai to Čatež presented the author's nationalist ideas about Slovenia and the Slovenian language.56

As in the preceding century, the collection of empirical data about people, places, flora and fauna remained popular. Contrary to the claims of authors, such accounts not only contained objective observations and geographical data, but also the travellers' subjective impressions and perspectives that served various commercial and strategic purposes, ranging from state-funded largescale operations to self-financed one-(wo)man undertakings.57 Such explorations usually led the travellers beyond Europe and were intended to fill "blank spaces" on European maps, or to collect foreign species and observations about peoples.

In Africa, the northeast of the continent – with the search for the sources of the Nile – and the west coast were the most popular travel destinations. However, an increasing number of travellers also explored central and southern Africa, among them David Livingstone (1813–1873)[ ], Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890), John Hanning Speke (1827–1864), Alexandrine Tinné (1835–1869), Emil Holub (1847–1902), Mary Kingsley (1862–1900), and Oskar Baumann (1864–1899).

], Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890), John Hanning Speke (1827–1864), Alexandrine Tinné (1835–1869), Emil Holub (1847–1902), Mary Kingsley (1862–1900), and Oskar Baumann (1864–1899).

In the Americas, North America continued to be featured most frequently, particularly the description by Meriwether Lewis (1774–1809) and William Clark (1770–1838) of their crossing of the United States, and those by the political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) and the Canadian settler Catharine Parr Traill (1802–1899). However, South America regained its popularity, as highlighted by the famous accounts by Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859)[ ] and Charles Darwin (1809–1882). On his voyage on HMS Beagle, Darwin also reached the South Pacific, Australia, and southern Africa. Charles Sturt (1795–1869), Louisa Anne Meredith (1812–1895) and others explored Australia and Tasmania, while John Ross (1777–1856), William Edward Parry (1790–1855), and Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930) travelled the Arctic.

] and Charles Darwin (1809–1882). On his voyage on HMS Beagle, Darwin also reached the South Pacific, Australia, and southern Africa. Charles Sturt (1795–1869), Louisa Anne Meredith (1812–1895) and others explored Australia and Tasmania, while John Ross (1777–1856), William Edward Parry (1790–1855), and Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930) travelled the Arctic.

In Asia, the Ottoman empire, Jerusalem and also India remained popular destinations that were visited frequently, for example by Francis Arundell (1780–1846), and Prince Bojidar Karageorgevitch (1862–1908). Other authors travelled around or across the globe and wrote numerous accounts, like Ida Pfeiffer (1797–1858)[ ], Ida Hahn-Hahn (1805–1880), and Isabella L. Bird (1831–1904).

], Ida Hahn-Hahn (1805–1880), and Isabella L. Bird (1831–1904).

While in previous centuries travelogues had already been highly ethnocentric and had been informed by ideas of European superiority, these tendencies deepened during the 19th century. Increasing European dominance across the globe was accompanied by imperialistic ideas, which were reflected in travelogues. Racial categorizations and representations of foreign cultures and places as "backward", "savage", and "superstitious" fostered and strengthened negative stereotypes and prejudices, many of which linger on to this day. As Edward W. Saïd (1935–2003) has pointed out in his influential monograph Orientalism, such negative representations of people and places outside of "the West" served colonial and imperialistic purposes and had – and continue to have – a profound influence on all parts of European society.58 Almost all European authors of 19th-century travelogues wrote in accordance with these ideas. These ideas not only pervaded the travelogues, but also reverberated in all media and genres, such as adventure novels like Jules Verne's (1828–1905) Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (first edition: Paris 1872), Karl May's (1842–1912) Der Schatz im Silbersee (first edition as a book: Stuttgart 1894), and Rudyard Kipling's (1865–1936) The Jungle Book (first edition: New York 1894). Additionally, other exoticizing works of art , museum exhibitions, public lectures, panoramas, and dioramas as well as dubious advertisements, decorative household goods, and even children's songs and toys helped to reinforce stereotypical discriminatory representations. Such media circulated in most parts of society, from the homes of the wealthy to public parks, museums and hostelries; and the playrooms of children. In this way, travelogues and their repercussions fostered imperial attitudes across Europe.59 There were, however, always people who spoke out against the misconceptions of western supremacy and dominance, like Charles Darwin (1809–1882). He strongly opposed slavery and sought to counteract racist attitudes by describing natives in the Americas as being the equals of Europeans.60 Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840–1922) also opposed British colonial policies through his support of Pascha Ahmad Urabi (1841–1911) in Egypt.61

, museum exhibitions, public lectures, panoramas, and dioramas as well as dubious advertisements, decorative household goods, and even children's songs and toys helped to reinforce stereotypical discriminatory representations. Such media circulated in most parts of society, from the homes of the wealthy to public parks, museums and hostelries; and the playrooms of children. In this way, travelogues and their repercussions fostered imperial attitudes across Europe.59 There were, however, always people who spoke out against the misconceptions of western supremacy and dominance, like Charles Darwin (1809–1882). He strongly opposed slavery and sought to counteract racist attitudes by describing natives in the Americas as being the equals of Europeans.60 Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840–1922) also opposed British colonial policies through his support of Pascha Ahmad Urabi (1841–1911) in Egypt.61

Conclusion

European travelogues are products of their time. They reflect the diversity of people, ideas, concepts and objects, as well as the circulation of these throughout the modern period. None of them is objective, but each offers a unique perspective. Their diversity and popularity increased up to the 19th century, reflecting an increasing curiosity as well as a growing mobility and the expansion of European peoples, and their empires, cultures, literacy, and media. Travelogues bear testimony to genocide, exploitation, oppression, and war. They document racist, hegemonic, nationalist, and chauvinist ideas, but also empathetic, revolutionary, artistic, and inventive ones. As vehicles of all types of knowledges, they pointed out economic, ecological, and social opportunities and dangers. They bore witness to the benefits and damage connected with intercultural exchange. They inspired wonder, art and science, and gave voices to the privileged and underprivileged, familiar and foreign, oppressors and the oppressed. Some are works of art in their own right, or record customs, species, and art that have since been lost. They offer insights on the construction of boundaries, as well as how stereotypes and prejudices took shape and circulated in modern times. But most of all they represent an opportunity to explore all these topics.

Doris Gruber

Appendix

Sources

Andersen, Hans Christian: I Sverrig, Stockholm 1851. URL: http://runeberg.org/isverige/0001.html [2022-02-07]

Anghiera, Pietro Martire d': De orbe novo decades, Alcala de Henares 1530. URL: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/10B2A295 [2022-02-07]

Aulnoy, Marie-Catherine: Relation du voyage d'Espagne, Paris 1691. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k83295d [2022-02-07]

Berlioz, Hector: Mémoires de Hector Berlioz, membre de l'Institut de France: comprenant ses voyages en Italie, en Allemagne, en Russie et en Angleterre: 1803–1865, Paris 1878. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k36210w [2022-02-07]

Booth, William: In darkest England and the way out, New York 1890. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433075935522 [2022-02-07]

Boucher de La Richarderie, Gilles: Bibliothèque universelle des voyages, ou notice complète et raisonnée de tous les voyages anciens et modernes ..., vol. 1–6, Paris 1808. URL: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/102821C7 / URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b556983 / URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k65495624 [2022-02-07]

Breydenbach, Bernhard von: Peregrinatio in terram sanctam, Mainz 1486. URL: http://tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/show/inc-iv-98 / URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00026644-8 [2022-02-07]

Chateaubriand, François-René de: Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem, Paris 1811. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k96755222 [2022-02-07]

Coryate, Thomas: Coryats crudities, London 1611. URL: https://archive.org/details/coryatscrudities00cory/mode/2up [2022-02-07]

Custine, Astolphe de: La Russie en 1839, Paris 1843. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8622143t/f7.item [2022-02-07]

Daniell, Thomas / Daniell, William: Oriental Scenery: Twenty Four Views in Hindoostan, London 1795–1807. URL: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/book/oriental-scenery-twenty-four-views-in-hindoostan-drawn-and-engraved-by [2022-02-07]

Defoe, Daniel: Robinson Crusoe, London 1719. URL: https://nl.sub.uni-goettingen.de/id/1452400500 [2022-02-07]

Dickens, Charles: Pictures from Italy, Paris 1848. URL: https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10745929-3 [2022-02-07]

Du Camp, Maxime: Égypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie: dessins photographiques recueillis pendant les années 1849, 1850 et 1851, Paris 1852. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8626070m [2022-02-07]

Fontane, Theodor: Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg, Berlin 1862–1882, vol. 1–4. URL: https://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/fontane_brandenburg01_1862/9 [2022-02-07]

Golescu, Constantin: Însemnare a călătoriei mele, Constantin Radovici din Golești, făcută în anul 1824, 1825, 1826, Bucharest 1826.

Gunzinger, Christoph: Peregrinatio Compostellana, Vienna 1655. URL: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/1097B63A [2022-02-07]

Hakewill, James: A picturesque Tour in the Island of Jamaica, from drawings made in the years 1820 and 1821, London 1825. URL: https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/orbis:1266998 [2022-02-07]

Hakluyt, Richard: The principal navigations, voyages, traffiques and discoveries of the English nation, made by sea or overland, to the remote and farthest distant quarters of the Earth, at any time within the compasse of these 1600 yeres, London, 1599. URL: https://exhibits.stanford.edu/renaissance-exploration/catalog/bm352xx0901 [2022-02-07]

Hearne, Samuel: A Journey from Prince of Wales' Fort in Hudson's Bay, to the Northern Ocean …, London 1795. URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10466989-6 [2022-02-07]

Herberstein, Sigmund von: Rerum Moscoviticarum commentarii, Vienna 1549. URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00074095-9 [2022-02-07]

Istria, Dora d': La Suisse allemande et l'ascension du Moench, Paris u.a. 1856, vol. 1 – 4. URL: https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10453711-4 [2022-02-07]

Kindermann, Eberhard Christian: Die Geschwinde Reise auf dem Lufft-Schiff nach der obern Welt: Welche jüngsthin fünff Personen angestellet, ... , Berlin 1744. URL: http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000A46B00000000 [2022-02-07]

Kinglake, Alexander William: The invasion of the Crimea: Its Origin, and an Account of its Progress down to the Death of Lord Raglan, Edinburgh u.a. 1863, 1863–1887, vol.1–8. URL: https://archive.org/details/invasioncrimeai03kinggoog [2022-02-07]

Kipling, Rudyard: The Jungle Book, New York 1894. URL: https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00082635/00001 [2022-02-07]

Lassels, Richard: The voyage of Italy, or, A compleat journey through Italy, Paris 1670. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/gri.ark:/13960/t1mg90z6b [2022-02-07]

Levstik, Fran: Popotovanje iz Litije do Čateža, 1858.

Ludolphus, Suchensis: De itinere ad terram sanctam, Augsburg 1476. URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00054990-4 [2022-02-07]

Magnus, Olaus: Carta Marina Et Descriptio Septemtrionalium Terrarum Ac Mirabilium Rerum In Eis Contentarum Diligentissime Elaborata Anno Dni 1539, Venice 1539. URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00002967-7 [2022-02-07]

Martens, Friedrich: Spitzbergische oder Groenlandische Reise Beschreibung gethan im Jahr 1671, Hamburg 1675. URL: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/10972DE6 [2022-02-07]

May, Karl: Der Schatz im Silbersee, Stuttgart 1894.

Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Felix: Reisebriefe aus den Jahren 1830 bis 1832, Leipzig 1861. URL: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/104208A8 [2022-02-07]

Montalboddo, Fracanzio da: Paesi novamente retrovati et novo mondo da Alberico Vesputio Florentino intitulato "A la fin", Vicentia 1507. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k58988n/f251.item [2022-02-07]

Pesel, Paul: WArhafftyge vnd aigentliche verzaichnüs der Allerdurchleichtigisten großmechtigisten vnnserer aller gnedigisten herrn Kayser Karls des fünfften/ sambt seiner Kayser, Vienna 1531. URL: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/10A3B2F5 [2022-02-07]

Pighius, Stephanus Vinandus: Hercules prodicius, seu principis juventutis vita et peregrination, Antwerp 1587. URL: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/1032D52F [2022-02-07]

Plunket, Frederica: Here and There Among the Alps, London 1875. URL: https://archive.org/details/hereandthereamo00plungoog/ [2022-02-07]

Polo, Marco: Hie hebt sich an das puch des edeln Ritters vnd landtfarers Marcho Polo, in dem er schreibt die grossen wunderlichen ding dieser welt, Nuremberg 1477. URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00004552-7 [2022-02-07]

Pückler-Muskau, Hermann von: Aus Mehemed Ali's Reich, Stuttgart 1844, vol. 1–3. URL: https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10467815-6 [2022-02-07]

Ramusio, Giovanni Baptista: Delle Navigationi Et Viaggi, Venice 1554, vol. 1. URL: https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.9380#0001 [2022-02-07]

Radcliffe, Ann: Journey Made in the Summer of 1794, Dublin 1795. URL: https://nl.sub.uni-goettingen.de/id/0593000100 [2022-02-07]

Riedesel, Friederike: Die Berufsreise nach America: Briefe der Generalin von Riedesel auf dieser Reise und während ihres sechsjährigen Aufenthalts in America zur Zeit des dortigen Krieges in den Jahren 1776 bis 1783 nach Deutschland geschrieben, Berlin 1800. URL: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/108630DE [2022-02-07]

Salvator, Ludwig: Levkosia die Hauptstadt von Cypern, Prague 1873. URL: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/106A7E22 [2022-02-07]

Scheffer, Johannes: Lapponia, Frankfurt am Main 1673. URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10899183-7 [2022-02-07]

Schiltberger, Hans: Reisebuch, Augsburg 1477. URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00032863-8 [2022-02-07]

Seacole, Mary: Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, London 1857. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107109766 (ed. 2013) [2022-02-07]

Shelley, Mary: Rambles in Germany and Italy, in 1840, 1842 and 1843, London 1844, vol. 1–2. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433082459185 [2022-02-07]

Staël-Holstein, Germaine de: Corinne, ou L'Italie, Paris 1807. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1040720f [2022-02-07]

Stendhal: Rome, Naples et Florence, Paris 1817. URL: https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10718634-5 [2022-02-07]

Stephen, Leslie: The Playground of Europe, London 1871. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101073694554 [2022-02-07]

Sterne, Laurence: A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, London 1768. URL: https://digital.lb-oldenburg.de/sb/content/titleinfo/80384 [2022-02-07]

Swift, Jonathan: Gulliver's Travels, London 1726. URL: http://nl.sub.uni-goettingen.de/id/1049700500 [2022-02-07]

Veer, Gerrit de: Diarium nauticum, seu Vera descriptio trium navigationum admirandarum et numquam auditarum, tribus continuis annis factarum, a hollandicis et zelandicis navibus…, Amsterdam 1598. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1520194b [2022-02-07]

Verne, Jules: Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours, Paris 1872. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8600244d [2022-02-07]

Literature

Ableitinger, Alfred et al. (eds.): Erzherzog Johann von Österreich: 'Ein Land, wo ich viel gesehen': Aus dem Tagebuch der England-Reise, 1815/16, 2nd ed., Graz 2010.

Agai, Bekim: Die Inszenierung der eigenen Reise als gute Geschichte im Anatolien- und Syrienreisebericht von Şerefeddin Mağmumı̂ 1895/96 – Oder – Wie viel Reise steckt im Reisebericht?, in: Bekim Agai et al. (eds.): "Wenn einer eine Reise tut, hat er was zu erzählen": Präfiguration – Konfiguration – Refiguration in muslimischen Reiseberichten, Berlin 2013 (Narratio Aliena? 5), pp. 29–73.

Agai, Bekim et al. (eds.): "Wenn einer eine Reise tut, hat er was zu erzählen": Präfiguration – Konfiguration – Refiguration in muslimischen Reiseberichten, Berlin 2013 (Narratio Aliena? 5).

Alam, Muzaffar / Subrahmanyam, Sanjay: Indo-Persian Travels in the Age of Discoveries: 1400–1800, Cambridge 2007.

Alù, Giorgia / Hill, Sarah Patricia: The Travelling Eye: Reading the Visual in Travel Narratives, in: Studies in Travel Writing 22/1 (2018), pp. 1–15. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/13645145.2018.1470073 [2022-02-07]

Andrade, Tonio et al. (eds.): Sea Rovers, Silver, and Samurai: Maritime East Asia in Global History, 1550–1700, Honolulu 2016 (Perspectives on the Global Past). URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9780824852771 [2022-02-07]

Angelier, François: Dictionnaire des voyageurs et explorateurs occidentaux: Du XIIIe au XXe siècle, Paris 2011.

Anghiera, Pietro Martire d': De orbe novo decades: I-VIII, edited by Rosanna Mazzacane, vol. 1–2, Genova 2005. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x030087069 [2022-02-07]

Ankenbauer, Norbert: "das ich mochte meer newer dyng erfaren": Die Versprachlichung des Neuen in den Paesi novamente retrovati (Vicenza, 1507) und in ihrer deutschen Übersetzung (Nuremberg, 1508), Berlin 2010.

Apostolou, Irini: Photographes français et locaux en Orient méditerranéen au ΧΙΧe siècle: Quelques cas de collaboration, in: Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem 24 (2013), pp. 2–15. URL: http://bcrfj.revues.org/7008 [2022-02-07]

Barta, Tony: Mr Darwin's Shooters: On Natural Selection and the Naturalizing of Genocide, in: Patterns of Prejudice 39/2 (2005), pp. 116–137. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/00313220500106170 [2022-02-07]

Bauer, Volker: Europe as a Political System, an Ideal and a Selling Point: The Renger Series (1704–1718), in: Nicolas Detering et al. (eds.): Contesting Europe. Comparative Perspectives on Early Modern Discourses on Europe: 1400–1800, Leiden et al. 2020, pp. 364–380. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004414716_017 [2022-02-07]

Bellingradt, Daniel: Flugpublizistik und Öffentlichkeit um 1700: Dynamiken, Akteure und Strukturen im urbanen Raum des Alten Reiches, Stuttgart 2011 (Beiträge zur Kommunikationsgeschichte 26).

Bender, Eva: Die Prinzenreise: Bildungsaufenthalt und Kavalierstour im höfischen Kontext gegen Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts, Berlin 2011 (Schriften zur Residenzgeschichte 6).

Bibliografie Reiseliteratur vom 18. bis 20. Jahrhundert, edited by Eutiner Landesbibliothek. URL: https://lb-eutin.kreis-oh.de/index.php?id=275 [2022-02-07]

Binney, Matthew W.: The Cosmopolitan Evolution: Travel, Travel Narratives, and the Revolution of the Eighteenth Century European Consciousness, Lanham 2006. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015064862660 [2022-02-07]

Binney, Matthew W.: The Rhetoric of Travel and Exploration: A New "Nature" and the Other in Early to Mid-Eighteenth-Century English Travel Collections, in: Revue LISA/LISA e-Journal: Littératures, Histoire des Idées, Images, Sociétés du Monde Anglophone – Literature, History of Ideas, Images and Societies of the English-Speaking World 13/3 (2015). URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/lisa.8687 [2022-02-07]

Bleichmar, Daniela: Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions & Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment, Chicago et al. 2012. URL: http://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226058559.003.0001 [2022-02-07]

Bleichmar, Daniela: Visual Voyages: Images of Latin American Nature from Columbus to Darwin, New Haven et al. 2017.

Böhme, Max: Die großen Reisesammlungen des 16. Jahrhunderts und ihre Bedeutung, Osnabrück 1985 [Reprint of Strasbourg 1904]. URL: https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_6FYNAQAAIAAJ (1904) [2022-02-07]

Borromeo, Elisabetta: Voyageurs occidentaux dans l'empire Ottoman (1600–1644): Inventaire des récits et études sur les itinéraires, les monuments remarqués et les populations rencontrées, vol. 1–2., Paris 2007 (Roumélie, Cyclades, Crimée).

Bossi, Maurizio et al. (eds.): Viaggi e scienza: Le istruzioni scientifiche per i viaggiatori nei secoli XVII–XIX, Florence 2005.

Boxer, Charles Ralph: The Christian Century in Japan 1549–1650, Berkeley 1951. URL: https://archive.org/details/christiancentury0000boxe [2022-02-07]

Bracewell, Wendy et al. (eds.): A Bibliography of East European Travel Writing on Europe, Budapest 2008 (East Looks West 3). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctv10tq5tr [2022-02-07]

Bracewell, Wendy: The Limits of Europe in East European Travel Writing, in: Wendy Bracewell et al. (eds.): Under Eastern Eyes: A comparative Introduction to East European Travel Writing, Budapest 2008 (East Looks West 2), pp. 61–120. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctv10tq5jm [2022-02-07]

Bracewell, Wendy et al. (eds.): Under Eastern Eyes: A comparative Introduction to East European Travel Writing, Budapest 2008 (East Looks West 2). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctv10tq5jm [2022-02-07]

Brauner, Christina: Das Verschwinden des Augenzeugen: Transformationen von Text und Autorschaftskonzeption in der deutschen Übersetzung des Guinea-Reiseberichts von Pieter de Marees (1602) und seiner Rezeption, in: Bettina Noak (ed.): Wissenstransfer und Auctoritas in der frühneuzeitlichen niederländischsprachigen Literatur, Göttingen 2014 (Berliner Mittelalter- und Frühneuzeitforschung 19), pp. 19–60. URL: https://doi.org/10.14220/9783737003100.19 [2022-02-07]

Brauner, Christina: Kompanien, Könige und caboceers: Interkulturelle Diplomatie an Gold- und Sklavenküste im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, Cologne et al. 2015 (Externa 8). URL: https://doi.org/10.7788/9783412502867 [2022-02-07]

Brenner, Peter J.: Einleitung, in: Peter J. Brenner (ed.): Der Reisebericht: Die Entwicklung einer Gattung in der deutschen Literatur, Frankfurt am Main 1989 (Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch 2097), pp. 7–13.

Brilli, Attilio: Quando viaggiare era un'arte: Il romanzo del Grand Tour, Bologna 1995 (Intersezioni 479). URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015037340158 [2022-02-07]

Brizay, Francois: Les récits de voyage de l'époque moderne: Bilan et perspectives de recherche, in: Tierce: Carnets de recherches interdisciplinaires en Histoire, Histoire de l'Art et Musicologie [En ligne], 2017. URL: https://tierce.edel.univ-poitiers.fr/index.php?id=275 [2022-02-07]

Buzard, James: The Beaten Track: European Tourism, Literature, and the Ways to 'Culture', New York 1993. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.02300 [2022-02-07]

Byrne, Angela: The Scientific Traveller, in: Alasdair Pettinger et al. (eds.): The Routledge Research Companion to Travel Writing, London 2020, pp. 17–29. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315613710 [2022-02-078]

Carey, Daniel et al. (eds.): Richard Hakluyt and Travel Writing in Early Modern Europe, Farnham 2012 (The Hakluyt Society Extra Series 47). URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315606415 [2022-02-07]

Chaney, Edward / Wilks, Timothy: The Jacobean Grand Tour: Early Stuart Travellers in Europe, New York 2014.

Clode, Danielle: In Search of the Woman who Sailed the World, Sydney 2020.

Clulow, Adam et al. (eds.): The Dutch and English East India Companies: Diplomacy, Trade and Violence in Early Modern Asia, Amsterdam 2018 (Asian History). URL: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv9hvqf2 / URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048533381 [2022-02-07]

Coleman, Simon / Elsner, John: Pilgrimage: Past and Present in the World Religions, Cambridge 1995. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x002653324 [2022-02-07]

Craciun, Adriana et al. (eds.): Curious Encounters: Voyaging, Collecting, and Making Knowledge in the Long Eighteenth Century, Toronto 2019 (UCLA Clark Memorial Library Series 26). URL: https://directory.doabooks.org/handle/20.500.12854/29335 / URL: https://doi.org/10.3138/9781487518486 [2022-02-07]

Cremer, Annette C. et al. (eds.): Prinzessinnen unterwegs: Reisen fürstlicher Frauen in der Frühen Neuzeit, Berlin et al. 2018 (Bibliothek altes Reich 22). URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110532937 [2022-02-07]

Damodaran, Vinita et al. (eds.): The East India Company and the Natural World, Houndsmills 2015. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137427274 [2022-02-07]

Das, Nandini / Youngs, Tim: Introduction, in: Nandini Das et al. (eds.): The Cambridge History of Travel Writing, Cambridge 2019, pp. 1–16. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316556740.001 [2022-02-07]

Das, Nandini et al. (eds.): The Cambridge History of Travel Writing, Cambridge 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316556740 [2022-02-07]

Daston, Lorraine / Park, Katharine: Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750, 2nd ed., New York 1998. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.05324 [2022-02-07]

Day, Matthew: Travelling in New Formes: Reissued and Reprinted Travel Literature in the Long Eighteenth Century, in: Mémoires du livre / Studies in Book Culture 4/2 (2013). URL: https://doi.org/10.7202/1016741ar [2022-02-07]

Díaz, Dorismel: White Voices, Black Silences and Invisibilities in the XIX Century Travel Narratives, in: La Palabra 26 (2015), pp. 17–29. URL: https://doi.org/10.19053/01218530.3182 / http://ref.scielo.org/7zknrs [2022-02-07]

Dović, Marijan / Helgason, Jón Karl: National Poets, Cultural Saints: Canonization and Commemorative Cults of Writers in Europe, Leiden et al. 2017 (National Cultivation of Culture 12). URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004335400 [2022-02-07]

Enenkel, Karl A. E. et al. (eds.): Artes Apodemicae and Early Modern Travel Culture: 1550–1700, Leiden 2019 (Intersections 64). URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004401068 [2022-02-07]

Englert, Birgit / Vlasta, Sandra: Travel Writing — on the Interplay Between Text and the Visual, in: Mobile Culture Studies. Travel 6 (2020), pp. 7–20. URL: https://unipub.uni-graz.at/mcsj/periodical/titleinfo/6012295 [2022-02-07]

Flaskerud, Ingvild et al. (eds.): Muslim Pilgrimage in Europe, London et al. 2018 (Routledge Studies in Pilgrimage, Religious Travel, and Tourism). URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315597089 [2022-02-07]

Foliard, Daniel: Orientalismes? Pionniers français et britanniques de la photographie au Levant, in: Études photographiques 34 (2016). URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/3605 [2022-02-07]

Friedrich, Susanne et al. (eds.): Transformations of Knowledge in Dutch Expansion, Berlin et al. 2015 (Pluralisierung & Autorität 44). URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110366174 [2022-02-07]

Fulda, Daniel: Plagiieren als wissenschaftliche Innovation? Kritik und Akzeptanz eines vor drei Jahrhunderten skandalisierten Plagiats im Zeitalter der Exzerpierkunst, in: Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte 43/2 (2020), pp. 218–238. URL: https://doi.org/10.1002/bewi.201900028 [2022-02-07]

Furui, Tomoko: L'ultimo missionario: La storia segreta di Giovanni Battista Sidotti in Giappone, Milan 2017.

Groesen, Michiel van: The Representations of the Overseas World in the De Bry Collection of Voyages (1590–1634), Boston et al. 2008 (Library of the Written Word 2). URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004164499.i-565 [2022-02-07]

Gruber, Doris: Frühneuzeitlicher Wissenswandel: Kometenerscheinungen in der Druckpublizistik des Heiligen Römischen Reiches, Bremen 2020 (Presse und Geschichte – Neue Beiträge 127). URL: https://www.editionlumiere.de/gruber.html [2022-02-07]

Gruber, Doris / Krickl, Martin / Rörden, Jan: Searching for Travelogues: Semi-Automatized Corpus Creation in Practice, in: Marius Littschwager / Julian Gärtner (eds.): Traveling, Narrating, Comparing: Travel Narratives of the Americas from the 18th to 20th Century, Göttingen 2022.

Gruber, Doris: German-Language Travelogues on the "Orient" and the Importance of the Time and Place of Printing, 1500–1876, in: Doris Gruber / Arno Strohmeyer (eds.): On the Way to the "(Un)Known": The Ottoman Empire in Travelogues (c. 1450–1900), Berlin et al. [forthcoming].

Habinger, Gabriele: Frauen reisen in die Fremde: Diskurse und Repräsentationen von reisenden Europäerinnen im 19. und beginnenden 20. Jahrhundert, Vienna 2006. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015066871396 [2022-02-07]