Introduction

From the perspective of transfer history, religion has played an important role in European history in a number of ways. On the one hand, as a phenomenon it shaped individual regions as religious and cultural areas and often influenced the designation of larger territories (e.g."Catholic Europe") as well as individual regions or places determined by religious difference. Religious infrastructures such as monasteries, bishoprics or sanctuaries, but also "negative" religious infrastructures such as the legal guarantee of asylum rights or religious freedom promoted the exchange of people

promoted the exchange of people , practices, objects, and ideas. "Religious" persons in the sense of the Latin religiosi – whether as temporary (pilgrims) or full-time religious representatives (clerics, nuns, monks) – and religious objects such as relics, ritual implements or books became the moveable elements of these transfer processes. The spaces in which these movements took place did not remain constant; rather, they were transformed by the gain, loss, or encounter between and with such persons and objects. These processes were not particularly effective because of their scale, the number of people involved or the amount of mobile objects. Having a more lasting effect was the selectivity to which they were subject. Religion not only reinforced existing differences of a social, ethnic, or linguistic nature, but it also created new differences itself. These were manifested as differences of religious competence or different degrees of sacredness between individual persons and objects, which generated different impulses or opportunities for movement: priests held prominent positions, not laymen; "relics"

, practices, objects, and ideas. "Religious" persons in the sense of the Latin religiosi – whether as temporary (pilgrims) or full-time religious representatives (clerics, nuns, monks) – and religious objects such as relics, ritual implements or books became the moveable elements of these transfer processes. The spaces in which these movements took place did not remain constant; rather, they were transformed by the gain, loss, or encounter between and with such persons and objects. These processes were not particularly effective because of their scale, the number of people involved or the amount of mobile objects. Having a more lasting effect was the selectivity to which they were subject. Religion not only reinforced existing differences of a social, ethnic, or linguistic nature, but it also created new differences itself. These were manifested as differences of religious competence or different degrees of sacredness between individual persons and objects, which generated different impulses or opportunities for movement: priests held prominent positions, not laymen; "relics" of saints wandered, not everyday objects. However, the differences created by religion could also create a difference of collective religious identities, differentiating majorities and minorities

of saints wandered, not everyday objects. However, the differences created by religion could also create a difference of collective religious identities, differentiating majorities and minorities from each other and among themselves. The individual consequences were difficult to predict: Protestants sought out other Protestants, Jews sought out other Jews, in order – positively – to be able to use infrastructures of their own religious practice. Or, they sought out Muslim jurisdictions in order – negatively – to be sure of the toleration of their own construction of such infrastructures. Religion promoted, hindered, and channeled communication and exchange processes. The concept of religion itself is not only a present-day concept of observation of such phenomena (including processes), but had itself become long before the early modern era an object-language phenomenon of great historical significance.

from each other and among themselves. The individual consequences were difficult to predict: Protestants sought out other Protestants, Jews sought out other Jews, in order – positively – to be able to use infrastructures of their own religious practice. Or, they sought out Muslim jurisdictions in order – negatively – to be sure of the toleration of their own construction of such infrastructures. Religion promoted, hindered, and channeled communication and exchange processes. The concept of religion itself is not only a present-day concept of observation of such phenomena (including processes), but had itself become long before the early modern era an object-language phenomenon of great historical significance.

The concept of religion

In early modern and modern Europe, the concepts of religion, which were circulating and increasingly elaborated in scientific terms, are characterized by a coincidence of two concepts that are not particularly prominent in non-European languages. Religion is understood, on the one hand, in an individual and at the same time generalizing way reflecting a "bond" to the divine or as a "re-reading" (also to be accomplished by individuals), i.e. careful observance, of divine prescriptions. Both concepts draw on ancient etymologies of religio as re-ligare or re-legere. In the transition from the 19th to the 20th century, humanities could very plausibly assume that every human being had a religion, as that corresponded to contemporary reality (e.g. in Germany, over 99 percent of the population were members of a confession). But even in late antiquity, religio was increasingly used to describe different conglomerations of religious practices and ideas, such as imputations of collective religious identities.1 This was connected with the implicit or explicit assumption that religion only exists in the form of religions. Such religions are understood as traditions of religious practices, beliefs, and institutions, possibly even organizations to which late Roman law ascribed the ability and task to regulate their own affairs in a legal manner. Narrative models for this were provided by the biblical conflicts of God's people with iconolaters, whether they worshipped wooden pillars or star constellations. Late antique legal and literary texts place Jews, Manicheans, heretics, and finally those who practiced sacrifice and unlawful divination alongside orthodox Christians. Subsequently, these were summarized as Hellenistic or Greek/Roman religion, which dominates in the non-Christian texts and imagery, pagani in Latin texts, polytheists in Jewish and Muslim understanding. In this way, there is a mutual classification and a pattern of perception that can also classify marginal or non-European cultures. Only gradually do the "naked philosophers" (yogis) of the ancient Indian discourse become their own "Indian" religion.2

In scientific terminology, "religions" have been regarded as products of societies, of groups of people usually living together within a territory, who withhold the essence of their coexistence – their common orientation through the use of religious symbols – from the purview of everyday discussion.3 This results – so the logic of such argumentation – in a system of signs that is kept alive in the performance of rituals and is safeguarded by priests. In images, narratives, written texts or sophisticated doctrines, it seeks to explain the world and to determine actions in terms of ethical imperatives – sometimes with the help of an enforceable sanction mechanism (e.g. through state support), sometimes without the threat of sanctions.

Postcolonial criticism accuses this concept of religion of being too narrowly oriented towards "Western," above all Christian, history of religion and concepts, which for instance could not be applied to Asian cultures.4 However, the presented variant of the concept is already insufficient for the European subject matter.5 With regard to the second, individual conceptual strand, religious affiliation is understood as being singular and exclusive. Beyond the normative and mostly institutionally secured core lie divergences in the form of systematized heresies or folk or popular religious practices and ideas. This could be evaluated positively, either critical of rationality or for the purpose of the formation of national or ethnic identity, and preserved by research or museumization. The spectrum can range from academic constructions of ethnic and religious continuity, for instance "Germanic" or "Aryan religiosity" (e.g. in the ancestral heritage of the SS) or in countless collections of "ex votos ".6 It is here, precisely in the context of the imperial European expansion, that the roots are found of the scientific discipline of the history of religion.7 In addition, a second narrative emerged that confronted religion with increasing individualization, which was brought about and in turn promoted by modernization. This view was linked to the assumption that earlier societies and their religions must have been characterized by a high degree of collectivism. The point of radical departure was sought precisely in one's own particular past after the "Dark Ages" of the European medieval period. According to the image devised already in the 19th century, the individual is a product of the Renaissance, which for the first time, with recourse to pre-Christian antiquity, made it possible to step outside one's own tradition.8 In the critical space thus opened up, it was possible to formulate, organize, and practice fundamental philosophical, aesthetic, linguistic, institutional, and even religious alternatives. If, at this point, one already sees paganism – and this remains disputed – not only as aesthetic form, but as religious alternative,9 then the result would be a strand of religious individualization that would find further room for maneuver in high and late medieval practices of piety. Indeed, this would be before the Reformation in the 16th century made religion the principle object of individual choice and opened up corresponding latitude for the individual. Since the 1960s, an intensification of this process has been observed in the "West" (and thus only parts of Europe), which is moreover interpreted as a complete dissolution of traditional bonds and the gradual invisibilizing of religion. This development goes hand in hand with the suppression of collective religion in favor of individual spirituality.10

".6 It is here, precisely in the context of the imperial European expansion, that the roots are found of the scientific discipline of the history of religion.7 In addition, a second narrative emerged that confronted religion with increasing individualization, which was brought about and in turn promoted by modernization. This view was linked to the assumption that earlier societies and their religions must have been characterized by a high degree of collectivism. The point of radical departure was sought precisely in one's own particular past after the "Dark Ages" of the European medieval period. According to the image devised already in the 19th century, the individual is a product of the Renaissance, which for the first time, with recourse to pre-Christian antiquity, made it possible to step outside one's own tradition.8 In the critical space thus opened up, it was possible to formulate, organize, and practice fundamental philosophical, aesthetic, linguistic, institutional, and even religious alternatives. If, at this point, one already sees paganism – and this remains disputed – not only as aesthetic form, but as religious alternative,9 then the result would be a strand of religious individualization that would find further room for maneuver in high and late medieval practices of piety. Indeed, this would be before the Reformation in the 16th century made religion the principle object of individual choice and opened up corresponding latitude for the individual. Since the 1960s, an intensification of this process has been observed in the "West" (and thus only parts of Europe), which is moreover interpreted as a complete dissolution of traditional bonds and the gradual invisibilizing of religion. This development goes hand in hand with the suppression of collective religion in favor of individual spirituality.10

These trends – themselves thwarted by counter-movements in the 21st century – question the religion qua religions concept precisely because they can be generalized by various pre-early modern and non-European phenomena, especially in the dialectics of individualization processes.11 The safeguarding of religious individuality through its institutionalization generated new norms and restrictions; denominationalization processes established group boundaries and ensured the internalization of specific confessional norms. They did not provide religious options that could be freely chosen anywhere.

A concept of religion has therefore been proposed as an appropriate analytical term that makes it possible to grasp precisely the individual practice and meaning of religion in the context of social and cultural contexts.12 Lived religion thus becomes tangible as a phenomenon of recognition of cultural artifacts and traditions.13 But even the latter are not simply given. Traditions are themselves the situation-specific products (or reproduction) of cultural actors; they can be shaped by local power relations as well as transregional exchange processes. In such complex situations, religious communications then include "divine" addressees of varying quality (gods, demons, angels, the deceased) that transcend the situation, attributing agency to them and endowing the actors themselves specific religious authority. The connection to long-lasting sacralizations of places, times, objects or role bearers (for Christian denominations such as churches, feast days, relics, clerics) make such actions plausible and can in turn make them permanent in "votives" or donations.14 From this perspective, what is now comprehensively referred to as "religion" can take on very different forms of institutionalization and self-reflective systematization; it can even become involved in very different ways in practices of individual and collective meaning-making and take on highly diverse functions.

State of the art

There is no coherent state of the art for research on religion in Europe. While the number of individual studies is legion, the attempt to tell a specifically European story before contemporary history is only tentative, which will be addressed at the end of this section. It is important to note that scientific observation of religion and concrete religious action are once again closely intertwined in this very history. Against the background of the two-sided concept of religion, religious (for the longest time especially Christian) actors and groups in Europe have made efforts to write and tell their own "history" in ever new alternate representations of the past.15 This has been linked genealogically to founding figures or events and showing the legitimacy and authenticity of the succession, or told as a history of demarcation describing the exclusion of illegitimate positions and groups. It is characteristic of the tradition of Western "secular" historiography that it is self-constituted in the criticism of mythical (Thucydides, 460–ca. 395), institution-legitimizing (Donation of Constantine ; Nicholas of Cusa, 1401–1464 / Lorenzo Valla, 1407–1457) and biblical narratives and, at the same time, finds its methodological precedents in the self-historicizations of Roman (Marcus Terentius Varro, 116–27 BC), Jewish (Hebrew Bible; Flavius Josephus, ca. 37/38–100) and Christian religion (Eusebios of Caesarea, ca. 260–340 BC). "Emic" and "etic" historiography, produced from an internal perspective and mostly for an internal audience or from outside and often for an academic audience, can hardly be separated. With regard to the opening and highly selective channeling of exchange processes, one of the greatest successes of "emic" historiography is the discussion of "Christianity," "Judaism," "paganism" (or "idolatry") and the heretical history that marks the aggregation of disqualifying limits. Despite countless crossovers of individuals, such groups appear as actors on the world stage that are clearly differentiated, stable, and unified. These clear group attributions do not correspond to empirical findings, as the term "folk religiosity"

; Nicholas of Cusa, 1401–1464 / Lorenzo Valla, 1407–1457) and biblical narratives and, at the same time, finds its methodological precedents in the self-historicizations of Roman (Marcus Terentius Varro, 116–27 BC), Jewish (Hebrew Bible; Flavius Josephus, ca. 37/38–100) and Christian religion (Eusebios of Caesarea, ca. 260–340 BC). "Emic" and "etic" historiography, produced from an internal perspective and mostly for an internal audience or from outside and often for an academic audience, can hardly be separated. With regard to the opening and highly selective channeling of exchange processes, one of the greatest successes of "emic" historiography is the discussion of "Christianity," "Judaism," "paganism" (or "idolatry") and the heretical history that marks the aggregation of disqualifying limits. Despite countless crossovers of individuals, such groups appear as actors on the world stage that are clearly differentiated, stable, and unified. These clear group attributions do not correspond to empirical findings, as the term "folk religiosity" [

[ ][

][ ] already demonstrates. The latter developed great appeal as a model for the self-organization of social groups as national or international actors. This proliferation of a contingent historiographical product, which was able to develop further popularity above all on the basis of the concept of "national identity" has always made the view of religious practices, texts, and ideas itself a matter of continual boundary demarcation – or the genealogical constructions of alliances such as those of the "Abrahamic religions."

] already demonstrates. The latter developed great appeal as a model for the self-organization of social groups as national or international actors. This proliferation of a contingent historiographical product, which was able to develop further popularity above all on the basis of the concept of "national identity" has always made the view of religious practices, texts, and ideas itself a matter of continual boundary demarcation – or the genealogical constructions of alliances such as those of the "Abrahamic religions."

The manner in which religions tell (their) history, on the one hand, and science reconstructs the history of religion and thus also religion, on the other, has so far only been partially investigated.16 The early modern preoccupation with the history of religion forms a kind of crossroads between the historicization in the "sources" that must necessarily be consulted and often have no alternative, and the scholarly historiography of religion (also often in ways in which religious actors set standards), which can be traced back to the critical examination of "paganism" and definitively leaves the realm of church history. So far, how biblical historiography – despite all modern historical criticism – persists in modern representations of the history of Israel and of ancient Judaism or early Christianity has hardly been critically reflected upon or examined. The way in which the self-historicization of religion is incorporated into denominational historiography is also only occasionally discussed.17 Even the classical phenomenology of religion, which aimed at an understanding from the outside,18 was in fact a philology of religion that concentrated primarily on theological texts of religious traditions.19 Intellectual transfer within the academic framework was thus also directed along the lines of institutional boundaries and shaped by the seductive proximity of the discursive practices of research (and presentation of research) and the discursive areas of its object.

The program of a "European history of religion" addresses this issue by focusing on the current state of research in the field of religious studies. The "European" of this concept does not refer to a given geographical space. Rather, it is already the result of a reflection on meaningful temporal and spatial boundaries for a history of religion that does not add up religions, but instead transverses them – which is appropriate to the definition of the subject matter outlined above.20 The typical constellations and pragmatic use of religious signs do not represent ahistorical "religions," but processes bound to place and time. Professionalization, monitoring of symbols, but above all the relationship to other cultural systems providing individual or collective orientation – in the case of European religious history, to "science", but also to law and economics – form such characteristics at an aggregated level. Examples of this would be economic rationalizations under the influence of religious ideas, from the work ethics of some forms of monasticism (Benedictines, Cistercians) to the "Protestant ethic." These examples also include the late antique Christian as well as rabbinical-Jewish adoption of Roman legal thought into their own forms of organization and way of life and the consequences of the formation of a systematic "canonical law" for the functioning and perception of "churches" up to the present day.

Preconditions

As content and prerequisite for the possibility of exchange processes, religion in the early modern period, i.e. parallel to the first transcontinental imperial advances, was determined by a number of spatial dynamics with religious connotations.21 A space marked by Latin as the language of instruction and writing, which already in late antiquity reached as far as Ireland, passed on a Christianity translated from Aramaic, but especially from Greek, that was unrivaled in the degree of its intellectual elaboration, capacity for material expression, and the number and strength of its organized structures. It may also have absorbed late ancient Latin Judaism to an unknown extent.22 On a local and national level, it presented itself as an ideology of dominion, partly in its prominent representatives even as rulers. From the earliest texts (Paulus, c. 50s, Acts of the Apostles, ca. second quarter second century), the reference to Christ as the Son of God was a transfer history with Rome and Jerusalem as main points of reference. Transfer narratives of legitimation and conversion (Constantine, ca. 270/288–337 / Helena, ca. 250–330; Charlemagne, 747–814; Crusades) produced a dynamic that have lasted into the present.

on a Christianity translated from Aramaic, but especially from Greek, that was unrivaled in the degree of its intellectual elaboration, capacity for material expression, and the number and strength of its organized structures. It may also have absorbed late ancient Latin Judaism to an unknown extent.22 On a local and national level, it presented itself as an ideology of dominion, partly in its prominent representatives even as rulers. From the earliest texts (Paulus, c. 50s, Acts of the Apostles, ca. second quarter second century), the reference to Christ as the Son of God was a transfer history with Rome and Jerusalem as main points of reference. Transfer narratives of legitimation and conversion (Constantine, ca. 270/288–337 / Helena, ca. 250–330; Charlemagne, 747–814; Crusades) produced a dynamic that have lasted into the present.

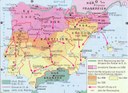

A further dynamic of exchange arose in the south and east from the circum-Mediterranean area in Greek, Arabic and Hebrew, which was quickly connoted by religious difference, e.g. Monophysite, Islamic, "Orthodox." These narrower contact zones, which were characterized in the High Middle Ages in Spain and Sicily by the intensive exchange (religiously above all in perception and translation) of texts had been replaced, along with the direct contact to Byzantium in the 15th century, by the shifting military border with the Ottoman Empire and a broad overlapping zone in the southeast of Europe, which was more strongly characterized by local exchange processes. Over time, these general conditions created dispositions for religious practices and ideas that were themselves capable of having a lasting effect. This broad, but strongly regionally shaped contact zone extended to the northeast in the political formations around the Russian Empire . As it included different Orthodox and Latin Christians and Ashkenazi Jews due to the expulsions from Western Central Europe, it was linguistically and religiously diverse. Even where religious exchange relationships were limited in terms of personnel and practices tended to "migrate" on a small scale, there were nevertheless networks of "weak ties" which, under certain conditions, could lead via urban centers to wide-ranging and rapid exchange processes of news and texts. This is demonstrated, for instance, by Hasidism, the movement of Shabtai Zvi (1626–1676)[

. As it included different Orthodox and Latin Christians and Ashkenazi Jews due to the expulsions from Western Central Europe, it was linguistically and religiously diverse. Even where religious exchange relationships were limited in terms of personnel and practices tended to "migrate" on a small scale, there were nevertheless networks of "weak ties" which, under certain conditions, could lead via urban centers to wide-ranging and rapid exchange processes of news and texts. This is demonstrated, for instance, by Hasidism, the movement of Shabtai Zvi (1626–1676)[ ],23 or Orthodox monastic practices. Luxury goods, which are also to be found especially in religious depositories like "church treasures"

],23 or Orthodox monastic practices. Luxury goods, which are also to be found especially in religious depositories like "church treasures" or were used as liturgical devices, were in any case unaffected by such restrictions. In this context, maritime exchange routes followed political and economic rationales. A secondary effect of the Reconquista in Spain

or were used as liturgical devices, were in any case unaffected by such restrictions. In this context, maritime exchange routes followed political and economic rationales. A secondary effect of the Reconquista in Spain was the expansion of networks of Sephardi Jews from Portugal all the way to Northern Europe.

was the expansion of networks of Sephardi Jews from Portugal all the way to Northern Europe.

Noticeably diminished was the dynamic of the missionizing paganism, of the ecclesiastical and – preceding or subsequent – political dominance in the form of religiously diametrically opposed cultures in North-Eastern Europe, Prussia and Scandinavia. Intensive processes of exchange are also visible here, but in many cases they remained local and only gained momentum from the periphery due to the developments of the 19th century mentioned above.

Religious identity and migration

The interactions between emigration and immigration experiences, on the one hand, and individual and collective religious identities, on the other, are complex. Today, they have become the subject of intensive research, especially in the social sciences. The insights gained from this invite a critical approach to the historiographical topos of religiously conditioned migration, which in turn had a major impact on religious self-interpretation and European historiography in the form of the biblical Exodus narrative.24 The impression of a permanent affiliation to a community determined by religious histories, ideas, ethos, or specifically religious institutions – all variables in themselves – can be quite different in its attribution as well as in one's own experience and can exhibit degrees of intensity, continuity, centrality, or exclusivity.25 Neither a single initiation ritual (baptism , circumcision for men) nor even repeated participation in rituals establishes a permanently actualized affiliation. Under these conditions, religion can be a source of legitimacy for emigration without serving as a vector for immigration – and vice versa. At the destination, a religious identity can be concealed or exchanged; it can contribute to the construction of legitimate difference under the conditions of religious plurality and then open up new networks. Here, too, the "aspirations" that drive migration can relate very differently to religious motives and goals.26

, circumcision for men) nor even repeated participation in rituals establishes a permanently actualized affiliation. Under these conditions, religion can be a source of legitimacy for emigration without serving as a vector for immigration – and vice versa. At the destination, a religious identity can be concealed or exchanged; it can contribute to the construction of legitimate difference under the conditions of religious plurality and then open up new networks. Here, too, the "aspirations" that drive migration can relate very differently to religious motives and goals.26

There is no doubt that religion, under the dominant European concept, entailed social capital, which could also be of great economic importance, especially in the case of migration in religious groups living in diasporas (Jewish Migration; Jainism ). Increasing territorialization and the significance of religious or denominational identities (whether attributed or appropriated) for the administrative registration of the population[

). Increasing territorialization and the significance of religious or denominational identities (whether attributed or appropriated) for the administrative registration of the population[ ] changed here the determining factors (sectarian migration) with respect to religiously pluralistic spaces in certain regions or in many cases port cities and hubs of the long-distance trade (Venice ;

] changed here the determining factors (sectarian migration) with respect to religiously pluralistic spaces in certain regions or in many cases port cities and hubs of the long-distance trade (Venice ; ).

).

Media and institutions

While religious practice is possible everywhere, it often relies on an infrastructure of sacralized places for individual or collective use or on non-sacralized but habitualized places of congregation. The latter usually requires short distances, i.e., it is local practice. Only in exceptional cases does the desire to use certain places involve long distances, which is called making a "pilgrimage". The practice of visiting cathedral churches a few days of the year lies in between. Here, specific salvation goods, enlightenment, forgiveness of sins, answering of prayers, healing, are expected from very distant places. Typically, this involves material signs (see below), graves of saints (also in Islam and Judaism), "relics" , and miraculous images and springs

, and miraculous images and springs . Possibilities of appropriating such signs in the theft of relics or exchange of gifts (holy graves/Jerusalem models as in Görlitz

. Possibilities of appropriating such signs in the theft of relics or exchange of gifts (holy graves/Jerusalem models as in Görlitz ) or to share them (contact relics, bone divisions) were sought and used by competing interests. This not only resulted in the movement of signs but made routes shorter and thus more attractive for visitors. Places and the practice itself were, and continue to be, subject to economic cycles. The Reformation and Counter-Reformation were inhibiting and promoting factors, but only the revolution of transportation, especially the advent of the railroad

) or to share them (contact relics, bone divisions) were sought and used by competing interests. This not only resulted in the movement of signs but made routes shorter and thus more attractive for visitors. Places and the practice itself were, and continue to be, subject to economic cycles. The Reformation and Counter-Reformation were inhibiting and promoting factors, but only the revolution of transportation, especially the advent of the railroad , made pilgrimages into a mass phenomenon from the 1850s onwards.27

, made pilgrimages into a mass phenomenon from the 1850s onwards.27

Long distance migrations of individuals were typically also triggered by the institution of "higher education" and "universities." This was first evidenced in the Middle Ages and then increasingly outside of church scope in the early modern period. The need was met not only for lawyers in the emerging city-state and territorial state (and also ecclesiastical) administrations, but theology also asserted itself, as in Paris or Oxford, as the supreme discipline.28

Since the Middle Ages, large church buildings have taken over the function of ancient temples or theaters as showpieces for municipalities, and not just as episcopal cathedrals . Often enough, this has happened at the very limits of economic possibilities or beyond, as the unfinished building projects in small as well as large towns and cities from the Rhenish Cologne

. Often enough, this has happened at the very limits of economic possibilities or beyond, as the unfinished building projects in small as well as large towns and cities from the Rhenish Cologne or the Flemish Lissewege (Ter Doest) to the neighboring Damme in the north of Bruges attest. Architecture of this type ensured outward visibility; inside, such a venue offered space for the contest for prestige between the inhabitants or those qualified as citizens in the form of tombs

or the Flemish Lissewege (Ter Doest) to the neighboring Damme in the north of Bruges attest. Architecture of this type ensured outward visibility; inside, such a venue offered space for the contest for prestige between the inhabitants or those qualified as citizens in the form of tombs or donations of sacral equipment and jewelry.29 The competitive process conducted in this way raised an awareness of other architectures and objects. Moreover, it led to the long-range movement of experts and their techniques and materials – when in doubt, in the semblance of local imitation, such as marble stucco or marble painting on wood. "Styles" spread rapidly in these media, which mobilized resources in the prestige contest in a particular way, comparable to a specific religious salvation economy.30

or donations of sacral equipment and jewelry.29 The competitive process conducted in this way raised an awareness of other architectures and objects. Moreover, it led to the long-range movement of experts and their techniques and materials – when in doubt, in the semblance of local imitation, such as marble stucco or marble painting on wood. "Styles" spread rapidly in these media, which mobilized resources in the prestige contest in a particular way, comparable to a specific religious salvation economy.30

Regional or supra-regional attractiveness through miracle-working relics or statues could decisively improve local standing, while at the same time become dangerous competition for sanctuaries in the region; the epiphany in the forest and the private chapel construction also represented a certain disempowerment of the local clergy.31 Theft of relics, consensual translation of relics or the creation of large relic ("Heilthum") collections (with the corresponding exhibition architecture)32 also decreased in Catholic dominated regions. Nonetheless, next to new epiphany sites like Fatima

(with the corresponding exhibition architecture)32 also decreased in Catholic dominated regions. Nonetheless, next to new epiphany sites like Fatima  or Lourdes, they remained important as an inducement for religiously motivated mobility, which, though mostly temporary, was also in some cases permanent.

or Lourdes, they remained important as an inducement for religiously motivated mobility, which, though mostly temporary, was also in some cases permanent.

A central medium for religious transfers in the early modern period was the calendar.33 Liturgical calendars had been local practices and documents in both antiquity and the Middle Ages – despite all attempts to unify at least some major festivals. "The" Reformation, which presented itself as a process of local church and liturgical reform, only intensified this. The Council of Trent (1545–1563) responded to the Reformation with a centralist reform agenda. The calendar reform in the wake of the Council (1582), which from today's vantage point appears as a technical reform, was actually only a subsidiary project of the introduction of a universal, primarily Roman liturgical calendar. Within the context of the confessionalization process since the end of the 16th century, there has been a regionally differentiated reaction to this development. On the Catholic side, the technical reform was adopted, but the abolition of local particularities was rejected or effectively circumvented by the further local modification of the universal calendar. It was only after this dissociation of the technical and liturgical reform project on the Catholic side was concluded that Protestant states were able, from 1700 onward, to agree to adopt the reform, which no longer had a primarily religious connotation.34 Nevertheless, calendars – printed and distributed in ever-larger numbers – remained a medium that could be filled with information and interpretations (in short: with knowledge), which could be likewise disseminated as norms and narratives ("calendar stories").

The conflict-laden potential of this process was especially evident in the German Empire in import bans and calendar monopolies or in the escalating civil war-like dispute in Augsburg of the years 1582/1583 in the aftermath of the Gregorian calendar reform. These developments took place in the wake of the consolidation of unstable and often small-scale territorial political units, which was accompanied by the expansion of a local and courtly festive culture. From Versailles to Dresden, from Venice to London, elaborately staged parades, performances, music and banquets, but also liturgical productions and fireworks impressed locals and visitors alike, as localities sought to distinguish themselves beyond their own borders. The export-oriented media representation of these festivities in the form of paintings, medals and printed picture sheets was correspondingly elaborate.35

in the form of paintings, medals and printed picture sheets was correspondingly elaborate.35

Practices and ideas

The aforementioned media provided their associated practices with a further, but also secondary, audience. Rites and the complex rituals known as "celebrations" were designed for visibility and personal observation, and thus led to mobility and transfers, whether by the specialists involved or mere spectators. Very different people and role bearers were brought together in such rituals – the initiators and invited guests, e.g. delegations from other cities, allies, or relatives - no less than fellow participants and those remaining on the periphery. Not only were universal religious celebrations an attraction, but so were celebrations related to individuals or groups. For instance, countless inhabitants of northern Italian cities lined the processions of urban brotherhoods. The forms of integration are vividly illustrated in the Venetian travelogue of Thomas Coryate (1577–1617), who witnessed an annual thanksgiving festival (July 10) to mark the end of a plague:

"It was on a Sunday when the Doge, in his official regalia, accompanied by the Senators in their robes of heavy red damask and other distinguished personalities, such as envoys and Knights of the Order, went to this church to hear Mass and praise God. For this feast, a wide bridge was built over the water, made up of cleverly assembled boats, over which boards were laid to make it easier for the people to get to the church and back. This bridge soon stretched for a mile from shore to shore, and I saw large crowds of people streaming across it into the church. Above the door of the church hung, from side to side, a large garland of fresh green leaves ... The thanksgiving celebration culminated here in a solemn procession in which all the religious orders and communities took part. They met here with their crosses and candlesticks, carried them into the church and then brought them back to their usual places ... In many places in the city all kinds of wine were served and cakes and other delicacies were distributed."36

Here, the ritual form of the procession takes on special significance. While it seized the public space in an almost aggressive way, it simultaneously made itself vulnerable to attack. From those areas where both denominations were allowed to participate, it is known for instance that Catholic and Protestant processions sometimes disrupted each other. But even more important in the report quoted is the omniscient narrator: He is the one who uses his text paradigmatically to spread knowledge of foreign practices and encouraged imitation.

takes on special significance. While it seized the public space in an almost aggressive way, it simultaneously made itself vulnerable to attack. From those areas where both denominations were allowed to participate, it is known for instance that Catholic and Protestant processions sometimes disrupted each other. But even more important in the report quoted is the omniscient narrator: He is the one who uses his text paradigmatically to spread knowledge of foreign practices and encouraged imitation.

The latter applied even to more mundane religious practices. The employment of the organ in Christian services and churches, which had already been in use in antiquity, had spread only very gradually in the High and Late Middle Ages. Originating from Byzantium, the organ was a very sophisticated and elaborate instrument, but in the early modern period it became almost ubiquitous in large parts of Latin Christianity (even beyond Europe).37 In the 19th century, organs also found a home in Jewish synagogues . Christian liturgical vestments and instruments were transported across Europe as gifts or commissioned works. The same is true of Christian practices in response to the new "pastoral" challenge of the rapidly growing industrial and large cities

. Christian liturgical vestments and instruments were transported across Europe as gifts or commissioned works. The same is true of Christian practices in response to the new "pastoral" challenge of the rapidly growing industrial and large cities .38

.38

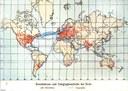

Universalism and globalization

Mutual awareness, material imports, the migration of individuals, and imitation were not limited to either the regional or the European context. Jewish, Christian, and Islamic views of history, indeed their fundamental, canonized writings, referred beyond the European region to the eastern Mediterranean and neighboring Syria and Arabia. Jewish and Christian origins, described in Spanish, Irish, Scandinavian or Russian narratives, were located in Palestine and Egypt; in Cordoba as well as Istanbul reference was made to the emergence of the Islamic Ummah in Mecca and Medina. Narratives of early Islamic expansion and the Crusades as well as their material relics sustained the idea and the excesses of religiously motivated expansion, while at the same time interpreting their own history as one of geographical expansion and migration. Such a history could be freely extended in and beyond Europe (Christian/Catholic[ ]/Protestant Mission). In its conceptual cancelling of political entities (despite all the conflicting practices), the idea of "world religions" was developed, which referred solely to the individual actor and his relationship to God and thus had to be disseminated transculturally.39 The concept programmatically pointed to the overcoming of all ethnic and spatial restrictions. With appropriate accommodations, including adaptations to local languages and habits (which from the Jesuits to Protestant missionary societies were continually the subject of fierce and long-lasting controversies), "world religions" could also be spread worldwide. Thus, in their predominant self-understanding, especially of Christian actors, this did not entail for Europeans the religious ideas and practices identified by others as "European." On the contrary, their own position was understood as universal, their own practices and religious ideas as universalizable. Religious difference could thus easily be interpreted as a civilizational divide and a civilizing (educational, medical, juridical) mission – even if, in individual cases (each with a limited spatial and temporal reach), the universalistic claims of one's own religion might result in unintended consequences (e.g. in the Paraguayan Jesuit state). As a rule, imperial expansion and even economic exchange beyond the borders of Europe (which for the Islamic advance into South Asia and into Sub-Saharan Africa formed an important, but only part of its own core area) was thus connected with a transfer of religious ideas and institutions. People and objects, identified at the outset of the article as basic elements of the history of religious transfer, were thus often subject to multiple codings or attributions, of which the religious variety were only one type.

]/Protestant Mission). In its conceptual cancelling of political entities (despite all the conflicting practices), the idea of "world religions" was developed, which referred solely to the individual actor and his relationship to God and thus had to be disseminated transculturally.39 The concept programmatically pointed to the overcoming of all ethnic and spatial restrictions. With appropriate accommodations, including adaptations to local languages and habits (which from the Jesuits to Protestant missionary societies were continually the subject of fierce and long-lasting controversies), "world religions" could also be spread worldwide. Thus, in their predominant self-understanding, especially of Christian actors, this did not entail for Europeans the religious ideas and practices identified by others as "European." On the contrary, their own position was understood as universal, their own practices and religious ideas as universalizable. Religious difference could thus easily be interpreted as a civilizational divide and a civilizing (educational, medical, juridical) mission – even if, in individual cases (each with a limited spatial and temporal reach), the universalistic claims of one's own religion might result in unintended consequences (e.g. in the Paraguayan Jesuit state). As a rule, imperial expansion and even economic exchange beyond the borders of Europe (which for the Islamic advance into South Asia and into Sub-Saharan Africa formed an important, but only part of its own core area) was thus connected with a transfer of religious ideas and institutions. People and objects, identified at the outset of the article as basic elements of the history of religious transfer, were thus often subject to multiple codings or attributions, of which the religious variety were only one type.

Jörg Rüpke

Appendix

Literature

Ahn, Gregor: 'Monotheismus' – 'Polytheismus': Grenzen und Möglichkeiten einer Klassifikation von Gottesvorstellungen, in Manfred Dietrich et al. (eds.): Mesopotamica – Ugaritica – Biblica: Festschrift für Kurt Bergerhof zur Vollendung seines 70. Lebensjahres am 7. Mai 1992, Kevelaer 1993, pp. 1–24.

Ankersmit, Frank R.: Historical Representation, Stanford, CA 2001.

Asad, Talal: Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam, Baltimore, MD 1993.

Bächtold-Stäubli, Hanns (ed.): Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens, Berlin 1927–1942, vol. 1–10. URL: https://www.degruyter.com/view/mvw/HWBDAB-B [2020-11-20]

Blackbourn, David: Wenn ihr sie wieder seht, fragt wer sie sei: Marienerscheinungen in Marpingen: Aufstieg und Niedergang des deutschen Lourdes, Reinbek 1997.

Borgolte, Michael: Christen, Juden, Muselmanen: Die Erben der Antike und der Aufstieg des Abendlandes 300 bis 1400 n. Chr., München 2006.

Burckhardt, Jacob: Die Cultur der Renaissance in Italien: Ein Versuch, Basel 1860. URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10860425-5 [2020-11-20]

Certeau, Michel de: Kunst des Handelns, Berlin 1988 (Internationaler Merve Diskurs 140).

Dingel, Irene et al. (eds.): Matthias Flacius Illyricus: Biographische Kontexte, theologische Wirkungen, historische Rezeption, Göttingen 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666570940 [2020-11-20]

Dobbelaere, Karel: The Contextualization of Definitions of Religion, in: Revue Internationale de Sociologie 21 (2011), pp. 191–204. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2011.544199 [2020-11-20]

Doerk, Elisabeth (ed.): Reformatio in Nummis: Luther und die Reformation auf Münzen und Medaillen: Katalog zur Sonderausstellung auf der Wartburg, 4. Mai bis 31. Oktober 2014, Regensburg 2014.

Durkheim, Émile: Die elementaren Formen des religiösen Lebens, Frankfurt am Main 2007.

Edrei, Arye / Mendels, Doron: A Split Jewish Diaspora: Its Dramatic Consequences, in: Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 16 (2007), pp. 91–137. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0951820706074303 [2020-11-20]

Edrei, Arye / Mendels, Doron: A Split Jewish Diaspora: Its Dramatic Consequences II, in: Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 17(2008), pp. 163–187. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0951820708089934 [2020-11-20]

Frazer, James: The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion, London 1890. URL: https://archive.org/details/b21904455 / URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100320953 [2020-11-20]

Fuchs, Martin et al. (eds.): Religious Individualisations: Historical Dimensions and Comparative Perspectives, Berlin 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110580853 [2020-11-20]

Fuchs, Martin / Rüpke, Jörg: Religious Individualisation in Historical Perspective, in: Religion 45 (2015), pp. 323–329.

Füssel, Marian: Die Kunst der Schwachen: Zum Begriff der 'Aneignung' in der Geschichtswissenschaft, in: Sozial.Geschichte 21 (2006) pp. 7–28. URL: https://www.academia.edu/746250 / URL: http://www.digizeitschriften.de/dms/resolveppn/?PID=PPN519763432_0021%7CLOG_0057 [2020-11-20]

Gladigow, Burkhard: Religionsökonomie: Zwischen Gütertausch und Gratifikation, in: Richard Faber (ed.): Aspekte der Religionswissenschaft, Würzburg 2009, pp. 129–140.

Gladigow, Burkhard: Religionswissenschaft als Kulturwissenschaft, Stuttgart 2005 (Religionswissenschaft heute 1).

Göttert, Karl-Heinz: Die Orgel: Kulturgeschichte eines monumentalen Instruments, Kassel 2017.

Grimm, Jacob: Deutsche Mythologie, Göttingen 1835. URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-db-id167101751X3 [2020-11-20]

Grundmann, Herbert: Religiöse Bewegungen im Mittelalter: Untersuchungen über die geschichtlichen Zusammenhänge zwischen der Ketzerei, den Bettelorden und der religiösen Frauenbewegung im 12. und 13. Jahrhundert und über die geschichtlichen Grundlagen der Deutschen Mystik, Berlin 1935 (Historische Studien 267).

Keith, Micheal: The Great Migration: Urban Aspirations, Washington D.C. 2014. URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/17602 [2020-11-20]

Kippenberg, Hans G. (eds.): Die Entdeckung der Religionsgeschichte: Religionswissenschaft und Moderne, München 1997.

Kippenberg, Hans et al. (eds.): Europäische Religionsgeschichte: Ein mehrfacher Pluralismus, Göttingen 2009 (UTB 3206).

Koch, Anne: Religionsökonomie: Eine Einführung, Stuttgart 2014 (Religionswissenschaft heute 10).

Kunert, Jeannine: Der Juden Könige zwei: Zum deutschsprachigen Diskurs über Sabbatai Zwi und Oliger Paulli: Nebst systematischen Betrachtungen zur religionswissenschaftlichen Kategorie Endzeit und soziodiskursiven Wechselwirkungen, Erfurt 2018. URL: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:547-201900030 [2020-11-20]

Luckmann, Thomas: Die unsichtbare Religion, Frankfurt am Main, 1991.

Mannhardt, Wilhelm: Wald- und Feldkulte: Antike Wald- und Feldkulte aus nordeuropäischer Überlieferung erläutert, Berlin 1905. URL: https://archive.org/details/waldundfeldkult04manngoog [2020-11-20]

Masuzawa, Tomoko: The Invention of World Religions: Or, how European Universalism was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism, Chicago 2005.

Masuzawa, Tomoko: The Production of 'Religion' and the Task of the Scholar: Russell McCutcheon Among the Smiths, in: Culture and Religion 1 (2000), pp. 123–130. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/01438300008567146 [2020-11-20]

Masuzawa, Tomoko: Secular by Default? Religion and the University Before the Post-Secular Age, in: Philip Gorski (ed.): The Post-Secular in Question, New York 2012, pp. 185–214. URL: https://doi.org/10.18574/9780814738733-008 [2020-11-20]

McCutcheon, Russell T.: Manufacturing Religion: The Discourse on sui generis religion and the Politics of Nostalgia, New York 1997. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.30846 [2020-11-20]

McLeod, Hugh et al. (eds.): European Religion in the Age of the Great Cities 1830–1930, London 1995 (Christianity and Society in the Modern World).

Metzger, Franziska: Religion, Geschichte, Nation: Katholische Geschichtsschreibung in der Schweiz im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert – kommunikationstheoretische Perspektiven, Stuttgart 2010 (Religionsforum 6).

Opacic, Zoë: Vienna's Heiltumstuhl: the Sacred Topography of Stephansplatz and its Context, in: Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte 62 (2014), pp. 81–108. URL: https://doi.org/10.7767/wjk-2014-0106 [2020-11-20]

Otto, Bernd-Christian et al. (eds.): History and Religion: Narrating a Religious Past, Berlin 2015 (Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten 68). URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110445954 [2020-11-20]

Pickering, W.S.F.: Emile Durkheim, in: J. Corrigan (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Emotion, Oxford 2008, pp. 438–456. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195170214.003.0025 [2020-11-20]

Rosati, Massimo: Ritual and the Sacred: A Neo-Durkheimian Analysis of Politics, Religion and the Self, England 2009 (Rethinking Classical Sociology).

Rüpke, Jörg (ed.): Creating Religion(s) by Historiography, Berlin 2018 (Archiv für Religionsgeschichte 20).URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/arege-2018-0001 [2020-11-20]

Rüpke, Jörg: Hellenistic and Roman Empires and Euro-Mediterranean Religion, in: Journal of Religion in Europe 3 (2010), pp. 197–214. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/187489210X501509 [2020-11-20]

Rüpke, Jörg: Privatization and Individualization, in: Steven Engler et al. (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of the Study of Religion, Oxford 2016, pp. 702–717. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198729570.013.47 [2020-11-20]

Rüpke, Jörg: Religious Agency, Identity, and Communication: Reflections on History and Theory of Religion, in: Religion 45 (2015), pp. 344–366. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2015.1024040 [2020-11-20]

Rüpke, Jörg: Lived Ancient Religion, in Oxford Encyclopedia of Religion, ed. John Barton, Oxford. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.633 [2020-11-20]

Rüpke, Jörg: Religious Agency, Sacralisation, and Tradition in the Ancient City, in: Istrazivanya 29 (2018), pp. 22–38. URL: http://istrazivanja.ff.uns.ac.rs/index.php/istr/article/view/2112/2133 [2020-11-22]

Rüpke, Jörg: Zeit und Fest: Eine Kulturgeschichte des Kalenders, München 2006.

Scheid, John: Polytheism Impossible; or, the Empty Gods: Reasons Behind a Void in the History of Roman Religion, in: History and Anthropology 3 (1987), pp. 303–325. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.1987.9960788 [2020-11-20]

Scheid, John / Durand, Jean-Louis: "Rites" et "religion": Remarques sur certains préjugés des historiens de la religion des Grecs et des Romains, in: Archives de Sciences sociales des Religions 85 (1994), pp. 23–43. URL: https://doi.org/10.3406/assr.1994.1424 / URL: www.jstor.org/stable/30128901 [2020-11-20]

Schleif, Corine: Donatio et memoria: Stifter, Stiftungen und Motivationen an Beispielen aus der Lorenzkirche in Nürnberg, München 1990 (Kunstwissenschaftliche Studien 58).

Schneider-Ludorff, Gury: Stiftung und Memoria: die Transformation des mittelalterlichen Stiftungswesens im 16. Jahrhundert und die Wirkungen auf Religion und Kultur in Europa, in: Cristianesimo nella storia 35 (2014), pp. 237–250.

Schreiber, Hermann: Venedigs goldener Herbst: Barocke Vermählung mit dem Meer, in: Uwe Schultz (ed.): Das Fest: Eine Kulturgeschichte von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, München 1988, pp. 199–209.

Stausberg, Michael: Renaissancen: Vermittlungsformen des Paganen, in: Hans Kippenberg et al. (eds.): Europäische Religionsgeschichte: Ein mehrfacher Pluralismus, Göttingen 2009, vol. 1, pp. 695–722.

Steindorff, Ludwig: Memoria in Altrussland: Untersuchungen zu den Formen christlicher Totensorge, Stuttgart 1994 (Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte des östlichen Europa 38). URL: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00042531-1 [2020-11-20]

Stemberger, Günter: Creating Religious Identity: Rabbinic Interpretations of the Exodus, in: Archiv für Religionsgeschichte 20 (2018), pp. 45–59. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/arege-2018-0004 [2020-11-20]

Veer, Peter van der: Handbook of Religion and the Asian City: Aspiration and Urbanization in the Twenty-First Century, Oakland, CA 2015. URL: https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520961081 [2020-11-20]

Wach, Joachim: Das Verstehen: Grundzüge einer Geschichte der hermeneutischen Theorie im 19. Jahrhundert, Tübingen 1926–1933, vol. 1–3.

Notes

- ^ Rüpke, Hellenistic and Roman Empires and Euro-Mediterranean Religion 2010, vol. 3, pp. 197–214.

- ^ Ahn, 'Monotheism' - 'Polytheism' 1993; see also Scheid, Polytheism Impossible or the Empty Gods 1987, pp. 303-325; Scheid / Durand, "Rites" et "Religion" 1994, pp. 23–43.

- ^ Durkheim, Die elementaren Formen des religiösen Lebens 2007; Pickering, Emile Durkheim 2008; Rosati, Ritual and the Sacred 2009.

- ^ Asad, Genealogies of Religion 1993; McCutcheon, Manufacturing Religion 1997; Masuzawa, The Invention of World Religions 2005; Masuzawa, The Production of 'Religion' and the Task of the Scholar 2000.

- ^ On the following criticism see Rüpke, Religious Agency, Identity, and Communication 2015.

- ^ For example, Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie 1835; Frazer, The Golden Bough 1890; Mannhardt, Wald- und Feldkulte 1905; Bächtold-Stäubli, Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens 1927–1942; see also Grundmann, Religiöse Bewegungen im Mittelalter 1935.

- ^ Kippenberg, Die Entdeckung der Religionsgeschichte 1997.

- ^ Burckhardt, Die Cultur der Renaissance in Italien 1860.

- ^ See Stausberg, Renaissancen 2009, vol. 1, pp. 695–722.

- ^ Luckmann, Die unsichtbare Religion 1991; Dobbelaere, The Contextualization of Definitions of Religion 2011, p. 198; Rüpke, Privatization and Individualization 2016.

- ^ Fuchs / Rüpke, Religious Individualization in Historical Perspective 2015, pp. 323–329; Fuchs, Religious Individualisations 2019.

- ^ See Rüpke, Lived Ancient Religion 2019.

- ^ For the concept of appropriation: Certeau, Kunst des Handelns 1988; Füssel, Die Kunst der Schwachen 2006, pp. 7–28.

- ^ Rüpke, Religious Agency, Sacralisation, and Tradition in the Ancient City 2018, pp. 344–366.

- ^ For the concept: Ankersmit, Historical Representation 2001.

- ^ Otto / Rau / Rüpke, History and religion 2015; Rüpke, Creating Religion(s) by Historiography 2018.

- ^ For example, Metzger, Religion, Geschichte, Nation 2010; Dingel, Matthias Flacius Illyricus 2019.

- ^ Wach, Das Verstehen 1926–1933.

- ^ Gladigow, Religionswissenschaft als Kulturwissenschaft 2005, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Kippenberg, Europäische Religionsgeschichte 2009.

- ^ Borgolte, Zur Entwicklung der Ausgangslage seit der Spätantike Borgolte, Christen, Juden, Muselmanen 2006.

- ^ Thus the (controversely discussed) claim of Edrei / Mendels, A Split Jewish Diaspora 2007, pp. 91–137; Edrei/Mendels, A Split Jewish Diaspora II 2008, pp. 163–187.

- ^ Kunert, Der Juden Könige zwei 2018.

- ^ In an exemplary manner: Stemberger, Creating Religious Identity 2018, vol. 20, pp. 45–59.

- ^ Rüpke, Religious Agency, Identity, and Communication 2015.

- ^ Keith, The Great Migration 2014; Veer, Handbook of Religion and the Asian City 2015.

- ^ For example Blackbourn, Wenn ihr sie wieder seht, fragt wer sie sei 1997.

- ^ Masuzawa, Secular by default? 2012.

- ^ E.g. Schleif, Donatio et memoria 1990; see also Steindorff, Memoria in Altrussland 1994; Schneider-Ludorff, Stiftung und Memoria 2014, pp. 237–250.

- ^ Koch, Religionsökonomie 2014; Gladigow, Religionsökonomie 2009.

- ^ Thus at Marpingen: Blackbourn, Wenn ihr sie wieder seht, fragt wer sie sei 1997.

- ^ See Opacic, Vienna's Heiltumstuhl 2014, pp. 81–108.

- ^ For the following, Rüpke, Zeit und Fest 2006.

- ^ In more detail, Rüpke, Zeit und Fest 2006, pp. 200–207.

- ^ Doerk, Reformatio in Nummis 2014.

- ^ Quotation from Schreiber, Venedigs goldener Herbst 1988, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Göttert, Die Orgel 2017.

- ^ See the contributions in McLeod, European Religion in the Age of the Great Cities 1830–1930 1995.

- ^ Masuzawa, The Invention of World Religions 2005.