Introduction

The spread of the originally non-European religion "Christianity" occurred in a polycentric fashion during the first 1400 years of its history. During the 14th and 15th centuries, a number of developments resulted in it temporarily becoming an almost exclusively European phenomenon. The almost total Christianization of Europe was concluded in the 14th century in the northeast of the continent, and the Iberian Peninsula also became predominantly Christian again as a result of the Reconquista. During the same period, Christianity was decisively weakened in Asia. The Apostolic Church of the East, the primary vehicle of missionary activity outside Europe, lost most of its ecclesiastical territory and area of distribution through the rise to power of the Ming Dynasty in China in 1368 and through the Islamization of large parts of Central Asia around 1400. Its remaining ecclesiastical territory in India found itself largely cut off from the central territory in Mesopotamia and from Europe. The Latin church of the west, which during the 13th and 14th centuries had attempted to form a church union with the Apostolic Church of the East in India, Central Asia and China, reacted to the new situation by issuing a number of papal statements (the most significant of which was the bull Romanus Pontifex of 1455

The Absence of Missions in Early Protestantism

The fact that the Europeanization of Christian missionary activity and the pluralization of European Christianity coincided with one another would lead one to expect that missionary activity emanating from Europe in the modern period would have been confessionally diverse from the start. However, this was not the case. There was a considerable delay before European Protestantism became involved in the further spread of the Christian faith outside Europe. The main reasons for this were, firstly, the fact that European Protestantism was divided territorially into state churches, which each viewed themselves as being bound to a political territory. They were occupied with the process of reorganization and of asserting their authority in their respective territories, and lacked a cross-border organizational structure. Within Lutheranism, the exclusive focus of state churches on their own territories was supported by the theory that the commandment to spread the Gospel was obsolete because the apostles of Jesus had already visited all nations. Secondly, the dominant position of the two Catholic powers Spain and Portugal in the early phase of European colonial expansion was an important factor in this regard. Thirdly, the dissolution of the monastic orders in the territories of the Reformation meant that there was initially no sociological group suitable for conducting missionary activity.

Consequently, the first waves of Protestant expansion outside of Europe were characterized by the absence of missionary activity rather than a targeted missionary strategy. After the British had brought an end to Spanish dominance in the Atlantic in 1577, it was primarily British and Dutch subjects who established overseas colonies, often at the expense of the Portuguese and the Spanish. The Dutch summarily redefined the Roman Catholic Christians living in their new colonies as Calvinists on the basis of the European principle of "cuius regio, eius religio" (whoever rules, his (is) the religion) – for example on the Maluku Islands after 1605 and in Sri Lanka after 1638 – and began to develop theoretical concepts for missionary activity among the non-Christian population. However, the number of clergy available was barely sufficient to minister to the Calvinist settlers. In the case of Sri Lanka, a study has shown how Indian Catholic priests succeeded in organizing an underground Catholic church there, which has resulted in Christianity in Sri Lanka remaining predominantly Catholic right up to the present.

The Beginnings of Protestant Missions in the 17th and 18th Centuries

The British colonies in North America developed quite differently. As a number of these colonies had been founded by religious minorities from England who had emigrated in search of religious freedom, there was broader scope in these colonies for independent initiative regarding the shaping of the religious order. In Massachusetts, the Puritan John Eliot (1604–1690) served as the leading clergyman of a church district from 1632, and in this capacity he established Christian communities among the natives from 1646 to his death. His understanding was that the Christian faith had to be connected with civic life, and he thus established a number of self-administered settlements for "praying Indians". The Quaker William Penn (1644–1718) founded the colony of Pennsylvania in 1682 and initiated there the "Holy Experiment" of a society in which the native Iroquois and settlers of every confessional affiliation were supposed to live together in "brotherly love" and complete religious freedom.

The earliest Protestant missionary project planned from Europe emerged from the collaboration between the Danish crown, the Francke Foundations founded from 1695 onward by August Hermann Francke (1663–1727)[

The first Protestant community to establish the beginnings of an infrastructure for the spread of Christianity worldwide was the Moravian Brethren in Herrnhut, which were founded in 1727 by Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf (1700–1760)[

The Revivalist Movement and Missionary Societies in the Long 19th Century

The foundation of a series of missionary societies from the late-18th century onward proved decisive for the organizational development of the Protestant missions. Missionary societies were associations of private individuals that were specifically formed for the purpose of collecting donations for the missions, training missionaries, sending them out, establishing missionary stations in foreign places while maintaining contact with the missionaries through the mission leadership in the country of origin in order to monitor their activities. It was this type of organization that enabled Protestantism to effectively compensate for the absence of monastic orders in its missionary activity compared with the Roman Catholic Church. However, the longer term consequences of this development were that missionary societies tended not to be institutions of the Protestant churches, but were instead private organizations whose donors and staff largely came from the revivalist movement, meaning there was often a degree of friction between them and the majority of the church membership and the church leadership of the Protestant state churches.

Among the most significant missionary societies (year of foundation in brackets) were the "London Missionary Society" (1795) and the "Church Mission Society" (1799) in Britain, and in the German-speaking territories the "Basler Mission" (1815), the "Berliner Mission" (1824), the "Rheinische Mission" (1828, having developed out of the "Missionsverein Elberfeld" founded in 1799), the "Leipziger Mission" (1836), the "Norddeutsche Mission" (1836) and the "Hermannsburger Mission" (1849). The "American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions" (ABCFM, 1810/1812) was the most significant missionary society in the USA.

An increasing emphasis on missionary activity can be observed in Protestant thought during the period when the missionary societies listed above were founded. In the revivalist movement, references in the Bible to spreading the Gospel were interpreted as referring to the remaining task of bringing the faith to all peoples worldwide. This idea had already been integral to the Moravian Brethren of Herrnhut, but it was popularized by a publication of the British Baptist William Carey (1761–1834) in 1792. During the course of the 19th century, further reasons were advanced for the urgency of this sense of mission. In view of technological advances and the new capabilities of steam ship travel, it was repeatedly argued that the present time offered more advantageous conditions for the truly global spread of the Gospel than any previous period in the history of the church and this implied a special duty to engage in missionary activity. The issue of religious freedom also played an important role in certain contexts. The events leading to the American Declaration of Independence and the French Revolution led William Carey to conclude that the guarantee of religious freedom would now spread throughout the world. Indications that rulers of individual territories around the world were now inclined to open their territories up to Christian missionary activity were repeatedly interpreted as divine providence and thus as an urgent duty to grasp the opportunity presented. Additionally, some streams of the revivalist movement had a strong expectation that the end of the world was destined to occur in the near future and a sense that as many people as possible should be brought to Christ before that happened. For example, over a period of time the year 1866 was frequently identified among ABCFM circles as the date of the end of the world. This tendency towards increased urgency culminated in the slogan formulated at a student missionary conference in Mount Hermon (Massachusetts) in 1886: "Evangelisation of the world in this generation!"

Evangelization, Bible Translation and Knowledge Transfer

In line with the spirit of the Reformation and the revivalist movement, effectively proclaiming the Bible and disseminating it in printed form were at the centre of the work of the Protestant missionary societies. Notwithstanding individual differences, the goal of all Protestant missionary work was to win people over to, and to instruct them in a Christian faith which was based on hearing and reading the Bible. Following the example of "revivalist" Protestantism in Europe and North America, the baptized were to gather together for Sunday services with a sermon based on a passage from the Bible, and were also to meet in gatherings to read and interpret the Bible together.

To make this possible, the early provision of Bible translations was seen as a priority – initially just parts of the Bible were translated and subsequently complete translations were provided

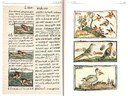

It is thus clear that the missionaries intended to transfer European knowledge to the missionary territories. However, what actually occurred was a much more complicated transfer of knowledge in both directions and the development of new transcultural knowledge. The first generation of missionaries in particular were very dependent on the assistance and advice of the native population both for their basic survival and in their spiritual task of adequately reproducing the Bible in the native language. This assistance related to adapting one’s diet and daily routine to the climate and local vegetation, finding one's way in the territory and protection against diseases, as well as knowledge of native cultures and religions, which was necessary not least in order to be able to use the local religious terminology appropriately in the Bible translation. However, numerous missionaries developed a deeper interest in native religion, culture, geography and history. They wrote down the knowledge they had acquired and passed it on to Europe and North America, where it was incorporated into newly emerging academic disciplines on non-European cultures (Orientalism, African studies, etc.). In many cases, written records by missionaries are the only remaining sources today for reconstructing the conditions of individual cultures before their encounter with Europeans. In the vast majority of cases, native people were directly involved in the preparation of Bible translations, as well as in the collection of materials for academic and more popular works

After the first generation of missionaries at a particular place, newly arrived missionaries were able to learn from their established predecessors and the consciousness of being directly dependent on the reciprocal exchange of knowledge with the native population often disappeared. Many missionaries then took the view that they should assert their authority in their dealings with their native colleagues and delay the transfer of leadership responsibility to natives. In retrospect, however, it is apparent that the European missionaries were effective primarily in the establishment of a missionary infrastructure that employed technological advances such as printing, while the spread of the Christian faith among the native population in many cases did not make substantial progress until control passed to a native elite.

Attitude to Native Cultures

In their dealings with the native cultures of their missionary territories, many Protestant missionaries of the 19th century were torn between a belief in modern progress and romantic ideas of a "primordial" society. In many regards, they were unequivocally convinced of the superiority of western civilization, for example as regards the usual forms of written communication in Europe, the technological advances in transportation and medical provision. The mission stations that were built under their supervision were often very European in their architectural design. In the case of the settlements established by the Moravian Brethren of Herrnhut in the 18th century it was conspicuous that the original settlement in Herrnhut (Saxony) was viewed as an ideal and repeatedly copied.

Conversely, Protestant missionaries often engaged in the discourses of romanticism, in which some aspects of modern civilization were criticized and an idealized concept of a connection with the past and with nature emerged. They often took a negative view on the growing urbanisation in European countries and the social transformations connected with the Industrial Revolution. Consequently, there are many examples of efforts to preserve elements of contemporary native culture which appeared valuable in the subjective perceptions of the missionaries and to assert the timeless value of these elements. The academic studies on cultural contexts already referred to above also served in part to document what existed for the purpose of protecting it against the dangers posed by western civilization. The most significant theoretician of this approach to pre-existing native cultures was the first Protestant holder of a professorship for missiology at Halle University, Gustav Warneck (1834–1910)[

Attitude to European Colonialism

Ideological discourses within the Protestant missionary movement during the long 19th century related to expanding European colonialism in much more nuanced ways than it is often perceived. In view of the stated duty of trying to reach all peoples of the world, cooperation with the colonial administration of one's own native country was always an option that was of very limited use, and many missionaries viewed colonialism as a hindrance to missionary work, particularly when it was the colonialism of another European country other than one's own.

In the British context, a positive attitude on the part of representatives of missions towards, and cooperation with colonial rule was most prominent in places where the British anti-slavery movement viewed colonial intervention as a suitable means for combating slavery both within Africa and between Africa and America. The occupation of Lagos by Britain in 1851 was credibly motivated by the intention of closing down the largest slave market on the west coast of Africa. Christianized and modernized Africans subsequently called for the expansion of British rule in Africa. In territories that were affected by wars between indigenous population groups, missionaries sometimes called for the territory to be taken under colonial rule in the hope of attaining peace and more security for the Christian communities – for example the "Rheinische Mission" in Namibia. The argument that colonial rule would assist the spread of civilization often played a role also.

Conversely, many missionaries deliberately asked to be sent to territories that were under the colonial rule of their own countries as they were of the opinion that the native population would only learn to appropriately deal with those aspects of European civilization which the missionaries themselves were ambivalent towards if they – the natives – were also introduced to Christianity. Others – for example the missionaries of the "Neuendettelsauer Mission" in Papua New Guinea – deliberately established their mission stations beyond the reach of colonial commercial enterprises because they viewed the influence of the latter (which included alcohol and enforced labour) to be so damaging that they preferred to protect those ethnic groups who had not yet been affected by that influence. Among Protestant missionaries, in addition to advocates of colonial rule there were also always staunch opponents of it, who campaigned for the rights of the indigenous populations and against the interests of settlers, commercial enterprises and colonial administrations. In addition to the consequences that the missionaries intended, the type of education (missionary schools) and the knowledge of the Gospel that they imparted played a big role in creating fertile ground for the independence movements of the 20th century, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Transformations in Protestant Missions in the 20th Century and the Ecumenical Movement

A specific problem of the Protestant missionary movement was its plurality. Out of the growing variety of Protestant denominations emerged an initially uncoordinated even larger number of missionary societies that were aligned to a greater or lesser extent with one of the confessions, which with the increasing concentration of the worldwide network of Protestant missionary stations ultimately found themselves competing with each other in the same territories. Competition with Catholic missions or with established Catholic or Orthodox churches was in some cases intended, where missionaries were of the view that only their own Protestant interpretation of the Gospel was suitable for fulfilling the commandment of Jesus Christ to proclaim the Gospel worldwide. However, internal-Protestant competition was increasingly viewed as a burden and became linked with the perception that it was disadvantageous for the spread of the Christian message if European and American Christianity made the full extent of its confessional divisions and infighting visible in the missionary territories. To counteract this, there were increasing efforts in the second half of the 19th century towards the international and inter-confessional coordination of missionary work. These efforts culminated in the World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh in 1910

Through the foundation in 1921 of the International Missionary Council, the World Missionary Conference became a permanent institution for the remainder of the 20th century, though its aims were substantially revised. Starting with the World Missionary Conferences in 1928 in Jerusalem and in 1938 in Tambaram (India), it became increasingly apparent that the confessional divisions within European Christianity were only the second biggest hindrance to the unity of Christianity worldwide. The largest problem was the hitherto completely one-sided definition of the relationship between the European and American missionary societies and the churches that they had founded in other regions of the world, which was characterized by the same Eurocentrism as European colonialism and which was by then subject to increasing criticism.

This provided part of the impetus for the foundation of the World Council of Churches, which at the time of its first assembly in 1948 was still overwhelmingly a Protestant institution but no longer exclusively an institution of the churches of the northern hemisphere. In 1961, the International Missionary Council was incorporated into the World Council of Churches.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the landscape of Protestant missions worldwide was completely reconfigured. Missionary activity was now defined as a task to be carried out by all the churches of the world in all the regions of the world (expressly including Europe) with no "one-way streets" and no differentiation between giving and receiving churches. During the process of the so-called "integration of church and missions", a large portion of the European missionary societies, which had previously operated as independent trusts, were converted into church institutions and missionary activity thus became the duty of the whole church. Simultaneously, the previously one-sided relationships between the missionary societies and the "young churches" founded by them were transformed into multilateral partnership relationships between churches in different regions of the world. This change was realized to a very large extent in the "United Evangelical Mission – Communion of Churches in three Continents ", which primarily emerged from the "Rheinische Mission", and the churches founded by it. People serving in the executive structures of the organization are drawn from all the member churches in a balanced way and particular emphasis is placed on the relationships between the African and Asian member churches. The programme of the organization also includes projects in the German member churches, who receive support from the other partner churches in the form of personnel and monitoring from an external perspective.