See also the articles "La colonisation" and "Slavery in European colonies" in the EHNE.

General overview

Until the 15th century, the land mass known today as Europe was nothing more than a peripheral adjunct to the geopolitically more significant Asia, feeding on its export of its goods and (increasingly) ideas.1 It is not possible to speak of any European "domination" of the world at this point. The "ancient world", consisting in the medieval and ancient period of Europe, North Africa and East Asia, was connected by the transfers of people, goods and ideas. Cross-border political systems of rule were not unknown, and the empire of Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.), the Imperium Romanum or even the upper-Italian merchant republics and their colonies extended their dominion eastwards, with the Vikings reaching westwards, establishing settlements on Greenland and North America. From the other direction, Islamic dynasties extended their sphere of rule to encompass Southern Italy and the Iberian Peninsula. At the height of their power, the Mongols controlled the Northern extent of the Eurasian land mass from the Pacific to the Oder. The Ottoman Empire established itself in Thrace and the Balkans, and after planting its capital city in Constantinople (1453), even extended into Europe for the first time.

The fifteenth century saw the beginning of a prolonged Spanish and Portuguese attempt to exploit Asian resources. After discovering a sea-route rounding Africa to India, the attempt to open a western route to the Spice Islands led to the accidental discovery of America.

Rule was much more than the exercise of power; it required instruments and techniques to ensure its successful enforcement. This end was served by a number of agents. Mission and the Church played an important role, just as did legal norms and ordinances, economic mechanisms and methods of exerting cultural influence. A variety of cultural transfer processes unfolded, both as an accompaniment to, and a consequence of, the establishment of a new form of dominion and the exercise of power.4 Although generating long-term structural dependencies, imperialism also inspired self-assertiveness in the colonized countries, resulting in a drive towards decolonisation. Indeed, unable to institute itself on violence and repression alone and requiring a certain extent of acceptance and collaboration, the mechanism of imperial rule often integrated local elites in the administrative process, thus according them a certain degree of influence. European imperialism made a decisive contribution to transforming the world. Nevertheless, the domestic repercussions in the metropole resulting from the rule of distant parts of the world and the insights gained from this experience resulted in significant changes in Europe itself.5

Forms and Agents

The first agents of European expansion were the mariners and explorers serving the Spanish and Portuguese crowns,![Vasco da Gama delivers the letter of King Manuel of Portugal to the Samorim of Calicut, ca. 1905 IMG "Vasco da Gama delivers the letter of King Manuel of Portugal to the Samorim of Calicut", photomechanischer Druck eines Gemäldes [?], USA, ca. 1905, John D. Morris & Company (Philadelphia); Bildquelle: Library of Congress, DIGITAL ID: (b&w film copy neg.) cph 3c05882 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c05882.](./illustrationen/herrschaft-bilderordner/vasco-da-gama-delivers-the-letter-of-king-manuel-of-portugal-to-the-samorim-of-calicut-ca.-1905-img/@@images/image/thumb)

The Portuguese moved into existing superregional trade networks,7 and exploited existing local rivalries in order to find a succession of local partners. Nevertheless, they did not shy from the use of violence. This dual policy enabled them to establish themselves in a number of niches in the Asian political and economic landscape. Operating in America, the Spanish profited from the structures of the pre-existing Mexican and Peruvian empires. They also exploited local conflicts, made use of the advantage of surprise, proceeding in a reckless, ruthless and inhuman fashion. An important ally in this process proved to be the European diseases to which they, but not the indigenous peoples were immune and which wiped out great numbers in the native populations.8 After smashing the local centres of power, the Spanish assumed the position of the old elites.

With the exception of Brazil, the Portuguese overseas empire was nothing more than a widely extended network of far-flung trading posts. The so-called Estado da Índia was administered from Goa, the residence of the viceroy and Archbishop, who carried responsibility for political and economic and spiritual questions respectively. Sovereignty lay with the Portuguese crown, and economic questions were decided by the Casa da Índia in Lisbon. The central control of business with Europe and a system of passports for Asian merchants were designed to create a Portuguese monopoly. The Spanish were unable to find any commodities in the new world which were able to compete with Asian products.

Rule over land and peoples resulted in a concept of colonial penetration different to the Asian system of staging posts. The administration and control of these possessions beyond the Atlantic was conducted in the spirit of absolutism, with the areas being governed from the motherland by the centralized royal bureaucracy. The "men on the spot" received a flood of directives, but the combination of geographical distance and extended communications furnished them with considerable freedom of action.9 The most lucrative economic activities were established as a crown monopoly.

With the arrival of the Dutch, English and French, a new set of actors entered the overseas stage. The newcomers chose the instrument of privileged trading companies through which to structure their interaction with the extra-European world.10 The leading role in this undertaking was played by private enterprise, with the state preferring just to "hold the ring". Companies were responsible not only for trade and plantation management; the founding and settling of colonies and their military, fiscal and administrative upkeep also fell within their remit. This was the age of mercantilism and the companies can be regarded as the forerunners of the modern corporation. Their rise to prominence took place against the backdrop of wars and conflicts. The Dutch, English and French stood against Portugal and Spain, but also fought each other. They competed not only for mastery in Europe, but also for spheres of influence in the colonial world that with its riches and resources was a coveted prize as well as providing an extended venue for European wars.

Prototypes of the chartered companies included the Dutch Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) and the English East India Company (EIC). Founded in 1602, the VOC was authorized to acquire land holdings, build fortresses, dispense justice, conclude contracts and conduct wars. It soon proved to be better financed, more effectively organized and better equipped than its Portuguese competitor and was able to break up its Asian trading network within a matter of years. The occasional use of armed force as well as the ability to take advantage of local divisions facilitated the VOC's establishment in Asia with Batavia![Grundriss von Batavia, 1629 IMG "Afbeldinge van 't Casteel en de Stadt Batavia…", kolorierter Stich von C. de Jonghe [?] nach M. du Chesne [?], Amsterdam: R. & J. Ottens 1740; Bildquelle: De Nationale Bibliotheek van Nederland in Den Haag, Sammlung Atlas Van Stolk, 3597-3, http://www.geheugenvannederland.nl/?/nl/items/ATVS02:17289.](./illustrationen/herrschaft-bilderordner/grundriss-von-batavia-1629-img/@@images/image/thumb)

The Spanish and Portuguese empires intensified their territorial rule in South America and in the North, British, French and other European settlers pressed on westwards.11 The companies' trading activities in Asia were increasingly transformed into a number of different systems of rule and paramountcy. In some parts of South Asia, the Dutch became not only territorial rulers, but also the regional hegemon. In India, the EIC used taxation and duties to alter the production structures within the Indian textile trade to its own advantage.12 Economic participation was also used as a political tool: in negotiating inner-Indian conflicts, (themselves part of the global rivalry with France), the EIC bought local support by conferring rights in revenue collection and the dispensation of administrative and civil justice.13

The long 19th century saw the increase of the area ruled by Europeans as well as an increase in the number of colonial powers, all of which took advantage of a number of more refined instruments of political rule.14 Colonialism transformed itself – particularly in the case of the British Empire – into imperialism and European dominion over the world. The requirement of the industrial economies for materials and markets, the search for investment opportunities, the desire of various governments to maintain an influence over expatriate settlers or the attempt to cushion the effects of domestic social and economic crises through the acquisition and exploitation of colonies fuelled this development. Extra-domestic factors also drove the march of imperialism – crises and disturbances within a colony, or conflicts with a neighbouring region could result in the intensification of colonial rule.

The British Empire was the unrivalled leader of the concert of powers. The range of its global interests was matched only by the variety of instruments employed to pursue them, the nature of which depended on both local conditions and the current geopolitical constellation. Its world power was founded on the Royal Navy, the expansion of which was made possible by progressive industrialization and the development of a system of deficit financing. Formal colonial rule was exercised in crown colonies, dominions – the colonies of white settlement – protectorates, League of Nations mandates and other legal constructions.15 The significant characteristic of "informal empire" included "unequal treaties", usually procured through "gunboat diplomacy" or other forms of pressure. By the mid 19th century, the areas subject to such penetration included sections of the Ottoman Empire, Persia, China and even Japan.16 If economic influence backed up by political-military pressure is also to be classified as a method of informal empire, then Latin America should be added to Britain's wider "informal empire".

Rule over persons and persons as agents of rule

Europe ruled not just over extra-European regions, but also people. The centres of colonial trade and economy required labour; should this requirement not be satisfied by immigration or the free market, then various systems of slavery were developed to meet demand.17 The Spanish used Indígenas to harvest a range of cash crops and mine for precious metals. After 1495 only prisoners of war were officially permitted to be enslaved and 1542 saw the final prohibition of slavery. Nevertheless, this did not see the end of forced labour which was continued by a number of devices. These included the systems of repartimiento (from the Spanish repartir – to allocate, distribute), and encomienda (from the Spanish encomender – to assign, entrust) under which a Spanish encomendero was assigned the labour force (and later their tribute) of a particular region in recognition of his service to the crown.

Physically in no way equal to the tasks allotted to them on the plantations of the Brazilian coastal region and Caribbean islands, the Indígenas died in great numbers. As a replacement, some 12 million black Africans were deported into slavery from Africa to the new world between 1450 and 1850. Approximately two million died during the march to the coast and moreover, during the passage. With low birth rates on the plantations, only continual replacement was able to maintain the numbers necessary for cultivation.18 Slaves (of both African and Asian origin) were also employed in the Dutch and British possessions in Asia, the French islands in the Indian Ocean and the Cape of Good Hope. Although also engaged in agriculture, they were predominantly used as house servants. Bearing more resemblance to a patron-client relationship than one of slavery, the working conditions in these territories were very much different to the situation to be found on the American plantations.

Approximately two million died during the march to the coast and moreover, during the passage. With low birth rates on the plantations, only continual replacement was able to maintain the numbers necessary for cultivation.18 Slaves (of both African and Asian origin) were also employed in the Dutch and British possessions in Asia, the French islands in the Indian Ocean and the Cape of Good Hope. Although also engaged in agriculture, they were predominantly used as house servants. Bearing more resemblance to a patron-client relationship than one of slavery, the working conditions in these territories were very much different to the situation to be found on the American plantations.

The abolition of the slave trade forced the planters to search for new sources of labour, finding them in forms of indenture. The majority of those filling this new labour relationship came from China and India, but Javanese, Filipinos and Melanesians also hired their labour to plantations, mines and railway companies. The contracts were not always entered voluntarily, but in contrast to slavery, the working relationships were always established on a contractual footing. The commitment to enter the service of an employer in a foreign land was (at least on paper) always made in return for contractually stipulated provisions regarding passage, working conditions, wages, accommodation and a return to their homeland.19

The African slave trade underscores the fact that European power over people greatly exceeded the boundaries of the colonial system. Europeans did not hunt for Africans themselves, nor did they buy them from their place of origin, preferring instead to purchase slaves from African middlemen who brought them to their coastal trading posts. Indeed, growing demand for slave labour led the slavers to extend their hunt into areas far removed from the Atlantic coast. The continual supply of fresh Africans was organized by native African empires which developed in the hinterland of the European settlements.20

European dominion was not the preserve of a small group of leaders: soldiers, merchants, craftsmen, farmers or even soldiers of fortune were able to profit from colonial structures and the asymmetric relationships of power. "Normal" settlers transformed the areas of settlement, bringing European pets, crops, pests, weeds and bacilli which had a lasting effect on the human and natural environment of the American South, Southern Africa, Australia, New Zealand and the Asian parts of Eastern Russia. Indeed, many speak of the establishment of a number of "neo-Europes".21 The use (indeed exploitation) of a native labour force by European settlers was part and parcel of colonial life. The establishment of plantation economies led to the development of overtly racist hierarchies22 whereas white settlers in the "neo-European" colonies preferred to perform the labour themselves. Settlers in the USA and Australia displayed little interest in obtaining the labour force of the Indians or Aborigines; indeed regarding them as disruptive factors, they preferred to marginalize, expel or even exterminate the native communities.23

In Europe, the exercise of overseas rule was not confined to banks and other internationally active firms; the members of academic institutions and a miscellany of colonial institutes were also drawn into the network of extra-European domination. Researchers from a variety of disciplines pursued their interests in a number of remote regions and a plethora of newly-founded associations and societies were dedicated to research into specific regions. These activities provided considerable assistance to the extension of colonial penetration and rule.24

Techniques of rule

Colonialism employed a number of techniques of rule, deploying military, administrative, legal and cultural power. The Spanish conquistadores took advantage of their superior fire-power to defeat the Aztecs and Incas; the naval technology of armed Portuguese and Dutch merchantmen were similarly able to achieve mastery of the Asian sea routes. Nevertheless, general European military superiority was established only in the course of the 19th century with the advent of conclusive European technological superiority. This was manifested in developments such as the advent of the steam powered gun boat (after 1830) and dynamite and machine guns in the 1850s. Medical advantages were also crucial in establishing European military superiority; the discovery of quinine for example enabled the large-scale deployment of European soldiers in tropical regions.25

The administration of colonial territories entailed by formal rule necessitated the development of a number of European-dominated institutions such as the Council of the Indies, vice regencies,![Lord George Curzon (1859–1925) IMG Portrait Lord George Curzon (1859–1925), schwarz-weiß Photographie, o. J. [zwischen 1898 und 1905], unbekannter Photograph, Bain News Service publisher; Bildquelle: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.16113, DIGITAL ID: (digital file from original neg.) ggbain 16113 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.16113.](./illustrationen/herrschaft-bilderordner/lord-george-curzon-185920131925/@@images/image/thumb)

The European rise to extra-European hegemony was also accompanied by great power rivalries and the proliferation of preventive action designed to deny others a competitive advantage.

The development of new forms of communication from the mid-19th century onwards provided further important techniques of rule. Replacing ship-bound communication involving passages of many months, deep-sea cable and telegraphy

Colonial power was also underpinned by the propagation of European cultural hegemony in the extra-European possessions, to which end the colonial powers made use of a range of instruments including religion, education, language![Bildpostkarte Missionsschule in Ruanda, um 1900 IMG Missionsschule in Rubengera am Kiwusee, Ruanda, farbige Bildpostkarte, o. J. [um 1900], unbekannter Urheber, Verlag: Bethel-Mission Bielefeld; Bildquelle: Zenodot Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Zeno.org, http://www.zeno.org/Bildpostkarten/M/Kolonien,+Mission/Afrika/Ruanda,+Missionsschule+in+Rubengera+am+Kiwusee.](./illustrationen/herrschaft-bilderordner/bildpostkarte-missionsschule-in-ruanda-um-1900/@@images/image/thumb)

Structural rule

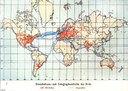

The unfolding of European world paramountcy resulted in the development of a North-South asymmetric relationship of dependency. The Eurocentric system of global trade produced dependencies and structural deficits, serving to hamper the independent development of the South and resulting in a diverging development of the two hemispheres by the mid-19th century at the latest. The South produced raw materials (usually in monoculture) for the North, which in turn exported capital goods and consumer durables to the South. Despite being aggravated by internal factors in the Southern hemisphere, the growth of the development gap between the two hemispheres was clearly the result of colonialism, serving as it did to truncate independent and balanced development in the South. Indeed, the progressive industrialisation of the Northern economies only increased further their ability to bind the Southern economies to them economically, socially and culturally.30

These dependencies were reinforced on the mental level. Locating itself at the vanguard of progress and modernity since the turn of the 19th century at the latest, Europeans accorded other cultures the status of (at best) children, to be raised to European standards. The new "science" of Social Darwinism conceived of this relationship as one of unalterable difference, a position based on crass racism. Having claimed the interpretative and definitional high ground, Europe was now able to impose its view of the nature and the value of other cultures on the rest of the world. The level of European civilisation, modernity and progress were contrasted to the barbarity, despotism and unregenerate nature of the overseas world.31

Resistance and decolonization

Resistance to colonial rule assumed a variety of forms. Many colonial insurgencies were strictly restorationist in nature, aiming merely at a return to the pre-colonial status quo ante. Over time, external impulses were incorporated into acts of resistance, which did not always assume a violent nature.32 Colonial resistance in plantation economies was characterized by slave escapes; other mechanisms of self-assertion operated in the cultural and religious sphere and were characterized by appropriation and adaption.33 Risings and rebellions were entirely unsuccessful in the core areas of colonial rule, yet peripheral insurgencies, especially in those areas where the indigenous peoples practiced nomadic lifestyles, often developed into enduring guerrilla campaigns.

Over the long-term, formal colonial rule proved itself to be unsustainable;

As the first wave of decolonization made clear, cession from the motherland did not result in full sovereignty in all matters. This was the case with the USA, but the former Spanish colonies in Central and South America merely freed themselves from "formal" into "informal" empire. Nevertheless, "informal empire" could be cast off as well. The turn of the 20th century saw successful Japanese revision of the series of unequal treaties to which she was subject. China discarded its imperial inheritance in 194935 and Fidel Castro's (1926–2016) seizure of power in Cuba (1959) can also be understood as part of a transition away from "informal empire".

Cultural transfer and change

Cultural hegemony as an instrument of rule also involved cultural transfer, which as in America or Australia, could also have highly destructive consequences and always resulted in processes of transformation and westernization in the colonized societies. The Southern societies consciously adopted, processed and integrated the elements of European culture introduced by their European political masters. Although involving losses, this development also presented a new context for cultural self-assertion. The mix of western influences and indigenous tradition produced a variety of creoles and syncretisms. Adoptions and inculturations of this nature did not serve to stabilize the established systems. Rather, they provided separatist and independence movements with new political ideas and forms of organization with which to question European rule.36

Religion and education did not just stabilize the colonial systems; they also provided ideas and reasons for their abolition. The imposition of European languages and orthographies as a common language provided the otherwise linguistically divided anti-colonial movements with a common language with which they could communicate. Indeed, after adopting a European language, the anti-colonial movements then established it as the language of resistance.37 Nationalism and constitutionalism – two of the defining political characteristics of 19th and 20th century Europe – provided the conceptional fodder for the independence movements. Democracies resembling (at least in appearance) the Western model are to be found throughout the post-colonial world.38 Socialist and Marxist ideology was also mainly a European import and provided the foundations for a number of liberation movements. Nevertheless, despite the varied nature of Western influence, a radical westernization of the colonized lands remained the exception. In the main, existing traditions mixed with western ideas in a number of different ways. Ideas developed for western civic or Socialist industrial society were translated into an African or Asian context. The proclamation of such "third ways" represented one option of combining the imports with local conditions.

Although subject to a process of westernization, the colonized cultures also succeeded in indigenizing much of what they adopted. As very few European women were to be found on the Asian system of trading posts, a mestee population soon grew with its own culture containing both European and Asian characteristics.39 Spain's territorial empire certainly enabled and even required a higher level of cultural export. Nevertheless, there is not one instance of an "Atlantic new Spain" cast entirely in the image of the motherland. The colonies of white settlement in America, Oceania and the Cape of Good Hope doubtless represent the Europeanization of the New World, but cannot just be conceived as mere copies of the Old.

The impact of colonialism on the metropole and ambivalences

Europe could not expect to rule larges swathes of overseas territory without itself undergoing various processes of change. The act of experiencing and understanding the new lands and their cultures transformed conventional perceptions resulted in their being questioned and sometimes even discarded. The debate over the legal status of the Indian communities in America and the legitimacy of Spanish claims to rule resulted in the development of the first principles of modern international law.40 In a similar fashion, the debate initiated by various pietist and revivalist movements and culminating in the abolition of slavery inspired the subsequent general discussion regarding the formulation and codification of universal human rights. The political developments in the USA led to intensified discussions of constitutional questions. New Zealand and South Australia assumed a pioneering position in the question of female suffrage. As a result, when compared to the motherland, Australia proved herself to be increasingly more egalitarian, democratic and less convention-bound; modes of behaviour envied by many Europeans. Colonial revolts or attempts at decolonization found support in Europe and left their mark in the politics and culture of the metropolitan centres. The Indian Mutiny of 1857 was followed with great interest in Ireland, itself effectively part of the British Empire. Mahatma Gandhi and his campaign of passive resistance provided inspiration for the various European movements of peaceful subversion and protest.

The political developments in the USA led to intensified discussions of constitutional questions. New Zealand and South Australia assumed a pioneering position in the question of female suffrage. As a result, when compared to the motherland, Australia proved herself to be increasingly more egalitarian, democratic and less convention-bound; modes of behaviour envied by many Europeans. Colonial revolts or attempts at decolonization found support in Europe and left their mark in the politics and culture of the metropolitan centres. The Indian Mutiny of 1857 was followed with great interest in Ireland, itself effectively part of the British Empire. Mahatma Gandhi and his campaign of passive resistance provided inspiration for the various European movements of peaceful subversion and protest.

In contrast to other cultures, Europe formed and reformed its identity through a continual process of self-affirmation. Despite an assertion of cultural and technical superiority over the New World, Japan, China, India, Siam, Persia and the Ottoman Empire were still perceived as Europe's cultural equal until well into the 18th century. Admiration (and even fear) of well-organized non-European state systems was wide-spread. Indeed, the horrors of the Thirty Years War had sewn doubt in Europe about the soundness of its own political, social and religious settlement. The Chinese Empire and the rule of the Tokugawa Shoguns in Japan also seemed to represent attractive models of government to many Europeans.

Nevertheless, the turn of the 19th century saw the development of a European self-perception claiming a higher level of civilization, modernity and progressiveness than Asia.41 European self-confidence was accompanied by the negative characterization of the non-European "other". Orientals were now viewed as being irrational, timeless, despotic, heathen, barbaric, backward and effeminate. The European in comparison was stylized as being rational, Christian, civilized, progressive, dynamic and manly. Thus, despite retaining a residual inclination to self-criticism, doubt and cultural pessimism, a feeling of general European superiority was gaining increasing currency. Some even chose to identify romanticized "noble savages" in the colonies, whose habits and way of life pointed to the shortcomings of European society. They interpreted the colonies as vanishing points, providing alternatives to the materialism of industrial society, rationalism, the belief in progress and the progressive European spiritual-religious disenchantment.42

Outlook

Post-colonial states exhibit a number of weaknesses, rooted in their inability to have generated stable political structures during the colonial period. Moreover, as the product of Western cartographic arbitrariness, with no ethnic, cultural or religious logic underpinning their borders, they represent artificial constructs with little or no inner coherence. They remain economically, politically and culturally dependent on the countries of the Northern hemisphere, which represent the true centres of military, political and economic power. The various international organizations are also dominated by the countries of the Northern hemisphere. Even in an ever-more heterogeneous, complex and confusing world, the extra-European world can still be viewed in terms of "foreign domination".