See also the article "Migrations et identités artistiques" in the EHNE.

Introduction

No later than the beginning of the eighteenth century, undertaking an artist journey was linked to the Grand Tour – in German also known as the Kavalierstour ("cavalier's" or "gentleman's tour") – which until the rise of the European bourgeoisie was reserved to the nobility. As was noted in a 1981 study on travel images, "journeys with very different motivations emerged in the second half of the eighteenth century. In addition to the Enlightenment interest in the social conditions of foreign countries, scientific curiosity was aimed at theretofore unknown, uncivilized regions."1

– which until the rise of the European bourgeoisie was reserved to the nobility. As was noted in a 1981 study on travel images, "journeys with very different motivations emerged in the second half of the eighteenth century. In addition to the Enlightenment interest in the social conditions of foreign countries, scientific curiosity was aimed at theretofore unknown, uncivilized regions."1

In contrast to the artist journeys of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, some of the most prominent of which were undertaken by the painters and draughtsmen Maarten van Heemskerk (1498–1574), Pieter Bruegel (1525/1530–1569) and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)[ ], here a new, broader spectrum of themes and motivations emerged for the travelling artist. These lay principally in the discovery and observation of nature as well of foreign morals and customs. In contrast to lone travellers like Heemskerk, Brueghel and Dürer, who were interested above all in the exchange of individual experiences and their own artistic development, the motivation for travel in the eighteenth century was explicitly linked to scientific curiosity. Explanations of botanical, meteorological, and geological questions based on the precise observation of nature were of great interest to art circles, as they were fruitful for artists' own examination of how nature should be portrayed.2 Collaboration between artists and scientists increased, such as that between the Vesuvius expert William Hamilton (1730–1803) and the painter Peter Fabris (active 1756–1784), who explored Mount Vesuvius

], here a new, broader spectrum of themes and motivations emerged for the travelling artist. These lay principally in the discovery and observation of nature as well of foreign morals and customs. In contrast to lone travellers like Heemskerk, Brueghel and Dürer, who were interested above all in the exchange of individual experiences and their own artistic development, the motivation for travel in the eighteenth century was explicitly linked to scientific curiosity. Explanations of botanical, meteorological, and geological questions based on the precise observation of nature were of great interest to art circles, as they were fruitful for artists' own examination of how nature should be portrayed.2 Collaboration between artists and scientists increased, such as that between the Vesuvius expert William Hamilton (1730–1803) and the painter Peter Fabris (active 1756–1784), who explored Mount Vesuvius and its surroundings together, or that between the Alpine painter Caspar Wolf (1735–1783) [

and its surroundings together, or that between the Alpine painter Caspar Wolf (1735–1783) [ ] and the scholar Jacob Samuel Wyttenbach (1748–1830), who came together to explore and sketch the mountain landscape of Switzerland.3 As opposed to early modern artist journeys, this new form of travelling became an educational privilege of entire social classes, including the nobility and the bourgeoisie, which, as has just been described, was coming into being and developing its own particular learned interests. Now the artist was increasingly found in their company.4

] and the scholar Jacob Samuel Wyttenbach (1748–1830), who came together to explore and sketch the mountain landscape of Switzerland.3 As opposed to early modern artist journeys, this new form of travelling became an educational privilege of entire social classes, including the nobility and the bourgeoisie, which, as has just been described, was coming into being and developing its own particular learned interests. Now the artist was increasingly found in their company.4

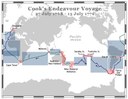

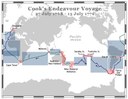

Part of being an aristocrat, especially in England, was rounding off the education of one's children by sending them on the Grand Tour. The point was to have them acquaint themselves with foreign mores and customs at European courts as well as to expose them to a classical education and urbanity. Beginning in the eighteenth century at the latest, it became common to have them accompanied not only by a tutor but also by a creative artist. Traditionally, the journey went through France to Italy and followed a fixed itinerary of spots deemed worthy of depiction. Eventually, a canon of attractions was formed that would go on to determine the further development of tourism.5 Although the itinerary and attractions were fixed, the Grand Tour – especially with regard to art – embodied a form of travel in which the experience of the foreign challenged individual, subjective perception. Until the mid-eighteenth century, foreignness still meant mostly European countries and the discovery of theretofore little known regions and sites of "foreign nature" – such as the unexplored mountains of the Alpine region or the volcanoes of southern Italy. But the interests of scientific exploration soon expanded to include far-off lands and continents.6 On his various voyages of discovery, James Cook (1728–1779) took several scientists with him who occupied themselves with questions of geology, botany and meteorology and who worked closely together with the artists participating in the journey. Louis-Antoine de Bougainville (1729–1811) was also accompanied by naturalists on his sailing voyage around the world (1766–1769) .7 These voyages into foreignness posed a challenge to European traditions of perception and knowledge. Even now, scholars still devote themselves to questions regarding how foreignness is experienced, how it is culturally conditioned, and to what extent these journeys occasioned processes of exchange or transfer that challenged the perception of the familiar and the foreign.

.7 These voyages into foreignness posed a challenge to European traditions of perception and knowledge. Even now, scholars still devote themselves to questions regarding how foreignness is experienced, how it is culturally conditioned, and to what extent these journeys occasioned processes of exchange or transfer that challenged the perception of the familiar and the foreign.

The journey to the Orient

In the late eighteenth century, a desire began to emerge for an "authentic, documentary travel report" of the Orient. In contemporary understanding, the Orient – more specifically the Near East – was reduced to the evidence and monuments of antiquity that were considered artistically valuable. Thus it was not landscape or the daily life of the inhabitants that were of note but rather the monuments – as witnesses to an impressive artistic past. Interest in and knowledge about Egypt and the Orient had never been lost in European history, as can be seen in the large number of travelogues and antiquarian collections.8 During the Enlightenment, however, the view of Egypt changed, such that in the late eighteenth-century there was talk of a rediscovery of the country.9 This altered perception of the Orient was characterized on the one hand by a desire for encyclopaedic knowledge about it, on the other by journeys made by artists who tested knowledge accrued from literature via "authentic seeing" ("authentisches Sehen"). The journeys' scholarly pretence found its artistic equivalent in the ideal of a true-to-detail representation and the related demand for verifiability. One of the most extensive expeditions to the Orient undertaken for this purpose is that of the Frenchman Louis-François Cassas (1756–1827). European acquaintance with ancient Egyptian cultural monuments was ultimately owed to his illustrations. In them Cassas developed an "archaeological portrait" of the Orient that would be authoritative for the Enlightenment's "image" of the region. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832)[ ], who in September of 1787 viewed Cassas's sketches from the Orient in the latter's studio in Rome, described them as follows in his Italian Journey:

], who in September of 1787 viewed Cassas's sketches from the Orient in the latter's studio in Rome, described them as follows in his Italian Journey:

A French architect by the name of Cassas has returned from his journey to the East. He has taken the measure of the most important old monuments, especially of such as have not yet been publicly described; he has also taken drawings of particular places, has by pictures illustrated decayed and vanished conditions of life, and has shown us a part of his drawings, sketched with great precision and taste with the pen, and enlivened by water-colour.10

Before Cassas travelled to the Orient, he visited locations that had become typical of the Grand Tour: Paris, Rome and Sicily – where he several times remained for longer periods. In the company of Marie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste, comte de Choiseul-Gouffier (1752–1817)[ ], an antiquities collector and member of the French high nobility, the artiste-archéologue Cassas travelled to Constantinople between 1784 and 1787. Choiseul-Gouffier was at the time France's ambassador to the Ottoman government, the Sublime Porte. With his journey to Greece and, from there, to regions of the Ottoman Empire, Cassas widened what had till then been the European horizon of his travels.11 On the comte's instructions, he undertook another journey that, over the course of fifteen months, brought him from Constantinople to Syria and Palestine and then to Egypt. As part of the mission, he rendered the most important regions, monuments, and people of these countries. During the journey he also assembled a portfolio of over 300 drawings. After his return to Rome in 1784, a plan was devised to publish a collection of engravings on the basis of his drawings.12 The political events of 1789, however, put his patron, Choiseul-Gouffier, in financial difficulties, and Cassas was forced to return to Paris to find new funds. The publication of the work was officially announced in Prospectus in the spring of 1789, where the unique character of this Voyage pittoresque was emphasized. The Voyage was to be illustrated with nearly 330 plates, among them 70 from Palmyra, 50 from Baalbek, 57 from Lower Egypt, 47 from Lebanon, 47 from Palestine, 17 from the northern Syrian cities of Aleppo and Antioch (on the Orontes), and 13 from Cyprus. Beginning in 1793, the draughtsman Cassas led one of the largest publication projects of the end of the eighteenth century, working together with 84 other people.13 The production of the publication was divided into several parts, with Cassas providing the drawings, preparing the contracts and overseeing the completion and arrangement of the plates, which were to be delivered in about fifty shipments of six plates each.14 On the basis of Cassas' drawings, about 100 different engravers in Paris produced the illustrations. Despite the support of Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) and Constantin-François Volney (1757–1820), state support was substantially reduced in 1802.15 The Voyage pittoresque remained unfinished and had to be interrupted in 1803/1804. The text explaining the plates, which had been announced in 1789, was never published. The work which had originally been planned with 330 engravings was ultimately reduced to a portfolio with 180 engravings and published under the title Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, die la Phénicie, de la Palestine et de la Basse-Egypte (Picturesque travels in Syria, Phoenicia, Palestine, and Lower Egypt)

], an antiquities collector and member of the French high nobility, the artiste-archéologue Cassas travelled to Constantinople between 1784 and 1787. Choiseul-Gouffier was at the time France's ambassador to the Ottoman government, the Sublime Porte. With his journey to Greece and, from there, to regions of the Ottoman Empire, Cassas widened what had till then been the European horizon of his travels.11 On the comte's instructions, he undertook another journey that, over the course of fifteen months, brought him from Constantinople to Syria and Palestine and then to Egypt. As part of the mission, he rendered the most important regions, monuments, and people of these countries. During the journey he also assembled a portfolio of over 300 drawings. After his return to Rome in 1784, a plan was devised to publish a collection of engravings on the basis of his drawings.12 The political events of 1789, however, put his patron, Choiseul-Gouffier, in financial difficulties, and Cassas was forced to return to Paris to find new funds. The publication of the work was officially announced in Prospectus in the spring of 1789, where the unique character of this Voyage pittoresque was emphasized. The Voyage was to be illustrated with nearly 330 plates, among them 70 from Palmyra, 50 from Baalbek, 57 from Lower Egypt, 47 from Lebanon, 47 from Palestine, 17 from the northern Syrian cities of Aleppo and Antioch (on the Orontes), and 13 from Cyprus. Beginning in 1793, the draughtsman Cassas led one of the largest publication projects of the end of the eighteenth century, working together with 84 other people.13 The production of the publication was divided into several parts, with Cassas providing the drawings, preparing the contracts and overseeing the completion and arrangement of the plates, which were to be delivered in about fifty shipments of six plates each.14 On the basis of Cassas' drawings, about 100 different engravers in Paris produced the illustrations. Despite the support of Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) and Constantin-François Volney (1757–1820), state support was substantially reduced in 1802.15 The Voyage pittoresque remained unfinished and had to be interrupted in 1803/1804. The text explaining the plates, which had been announced in 1789, was never published. The work which had originally been planned with 330 engravings was ultimately reduced to a portfolio with 180 engravings and published under the title Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, die la Phénicie, de la Palestine et de la Basse-Egypte (Picturesque travels in Syria, Phoenicia, Palestine, and Lower Egypt) ; some owners had it bound as a travelogue.16 The engravings and etchings produced are not simply the result of the artist's geographico-cultural journey from Europe to the Orient. Instead they are, like almost all other "images from the Orient," the product of a process of medial transfer. Begun as sketches made in front of the subject, in Rome and Paris they were diffused in the form of engravings and etchings. Some of the drawings could only be finished in colour in the years around 1820.17

; some owners had it bound as a travelogue.16 The engravings and etchings produced are not simply the result of the artist's geographico-cultural journey from Europe to the Orient. Instead they are, like almost all other "images from the Orient," the product of a process of medial transfer. Begun as sketches made in front of the subject, in Rome and Paris they were diffused in the form of engravings and etchings. Some of the drawings could only be finished in colour in the years around 1820.17

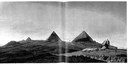

The etching Vue de la tête colossale du Sphinx et de la 2ème Pyramide d'Egypte (View of the colossal head of the Sphinx and the second pyramid of Egypt) , which was coloured in the Piranesi brothers' Paris chalcography studio, belongs to the "incunabula of European dreams of Egypt."18 It is emblematic of how the desire for a precise, true-to-detail portrayal – which would soon shape the principles of European scholarly disciplines like archaeology – came together with the traditional artistic conventions of European landscape painting. The head of the mythical creature is portrayed frontally and is the dominant element of the picture. In contrast to the actual geographical situation

, which was coloured in the Piranesi brothers' Paris chalcography studio, belongs to the "incunabula of European dreams of Egypt."18 It is emblematic of how the desire for a precise, true-to-detail portrayal – which would soon shape the principles of European scholarly disciplines like archaeology – came together with the traditional artistic conventions of European landscape painting. The head of the mythical creature is portrayed frontally and is the dominant element of the picture. In contrast to the actual geographical situation , the Sphinx's head appears in front of the Pyramid of Khafre, which looms in the background and frames the monument. The building stones of the Pyramid's lower section and the smoother limestone facing of the upper part are clear to see. The face, with its sightless eyes, appears fully reconstructed; only the hair shows signs of destruction.19 European and Oriental travellers with their mounts can be seen in the foreground. They are encamped around the monument, giving an impression of what the expedition was like. The Sphinx is huge relative to the Pyramid. The alteration of the proportions and the mysterious clouds rising behind the colossus underscore the massive impact of the Egyptian cultural monument. The portrayal of the light also contributes to the Sphinx's staging: its countenance seems to be illuminated by an imaginary light, making the features lively but without solving its riddle.20

, the Sphinx's head appears in front of the Pyramid of Khafre, which looms in the background and frames the monument. The building stones of the Pyramid's lower section and the smoother limestone facing of the upper part are clear to see. The face, with its sightless eyes, appears fully reconstructed; only the hair shows signs of destruction.19 European and Oriental travellers with their mounts can be seen in the foreground. They are encamped around the monument, giving an impression of what the expedition was like. The Sphinx is huge relative to the Pyramid. The alteration of the proportions and the mysterious clouds rising behind the colossus underscore the massive impact of the Egyptian cultural monument. The portrayal of the light also contributes to the Sphinx's staging: its countenance seems to be illuminated by an imaginary light, making the features lively but without solving its riddle.20

Where Cassas departs from the demands of documentation, he follows the artistic principles of European landscape painting, especially the conventions for portraying vedute, or idealizing images of a town or landscape. This can be seen clearly in the way the Sphinx is represented. Cassas adheres to the ancient ideals of the sublime and the beautiful, as they were formulated in the aesthetic categories of eighteenth-century English art theory.21 What was verified through "authentic seeing" in a foreign land is echoed only in specific sections of the picture: the precise observation and portrayal of the Pyramid's construction (building stones and limestone facing), the traces of destruction left by time and climate on the neck of the Sphinx, and the Orientals encamped in the foreground, portrayed in the European tradition of staffage.22

The artist's mode of representation evinces European traditions of image-making and perception that were confronted with the demand for autopsy during or after the return from the journey. With artists travelling more and more to regions outside the realm of European experience, a new criterion for artistic representation emerged. With a view to the artist's experiences and adventures in the foreign culture, the images he brought back ought to provide a kind of documentary evidence of his journey – evidence that also served to win him social prestige. It should be noted that many other travellers had visited Egypt before Cassas began his sojourn there in March of 1785. Some of their reports contributed to making the Land of the Pharaohs known in Europe and to sparking a yearning for Egypt. Among these works of travel literature were two that Cassas bought upon his return to Paris in 1791: the Dane Frederik Ludvig Norden's (1708–1742) Voyage d'Egypte et de Nubie (Travels in Egypt and Nubia),23 published in 1751/1755 and illustrated with plates that were often purely fictitious, and the Englishman Richard Pococke's (1704–1765) 1771/1772 work Voyages en Orient dans l'Egypte, l'Arabie […] (Travels in the Orient, in Egypt, Arabia […]),24 also published in French. It can be assumed that Cassas used these works about Egypt to edit his own experiences after the fact.25 His travel route also follows stations that had been visited by many travellers before him: reaching the port of Damietta from Palestine, he travelled up the Nile to Cairo. As with the European Grand Tour, fixed stops were soon established along routes through the geographically remote regions of the Orient, which led, by the end of the eighteenth century, to the emergence of a canon of ancient Egyptian attractions.26 With the exception of Norden's plates, however, no traveller had yet brought "true images" from Egypt to Enlightenment Europe, and thus the new form of knowledge transfer between the Orient and Europe had not yet been initiated.27

In contemporary understanding, as can be ascertained from the artists' own descriptions, the "true image" is one that provides a precise, true-to-detail, and verifiable view of the subject. Here we see the new interests of the travelling artist, which were applied to natural subjects as well as to those of the foreign culture. That this phenomenon was not restricted to the Orient can be seen in journeys undertaken by the French painter Jean-Pierre-Laurent Hoüel (1735–1813) and Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), to name only two examples that embody the increasing intersection of artistic and scientific interests. Between 1776 and 1779, Hoüel visited the islands of Sicily, Malta and Lipari. He was concerned primarily with volcanic phenomena and published his findings in his illustrated Voyage pittoresque des Isles de Sicile (Picturesque travels in the Sicilian Isles)28 (1782–1787).29 A similar case is Alexander von Humboldt, whose naturalist research brought him all the way to Latin America and who illustrated his own travelogue , for which he relied on his artistic training under Daniel Chodowiecki (ca. 1726–1801).30

, for which he relied on his artistic training under Daniel Chodowiecki (ca. 1726–1801).30

Another stop on Cassas's journey was Baalbek, a holy site located in the Beqaa Plain at the intersection of several roads that also belonged to the repertoire of travels to the Orient. Cassas reached Baalbek in June of 1785 and spent 20 days there, as he wrote to the ambassador, in which he occupied himself intensively with the architectural structures:

… It was fairly peaceful there. I sketched and measured the most important structures, which in their magnificence, nobility, and architectural purity are in no way inferior to the beautiful antiquities in Rome.31

The 1793 Landscape with the portal to the cella of the Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek embodies the principle of a landscape composed of nature and architecture.32 The portrayal exhibits both features of European Romantic landscape painting and the "observational pathos" of the Enlightenment, which is connected to the image's status as a witness. The portal to the cella, which Cassas portrayed in several attentive and true-to-detail architectural studies, is depicted as an ancient ruin overgrown with lush, fanciful vegetation. The distinctive feature of the temple (built 120 AD) is the keystone of the architrave, which slipped down during an earthquake in 1795. In his watercolour, Cassas exaggerated the displacement caused by the earthquake, depicting the entire wall as unstable. In addition, he slid the keystone towards the viewer, such that the sculptural detail of the soffit, a bird with outspread wings, is infused with drama. Travellers identified this image as an eagle, thus leading the temple to be identified as a Temple of Jupiter. The monumental portal presents itself to the viewer like an open window that gives a view onto a landscape with ancient ruins glittering in the distance. The theme of the ruins and their placement in nature, as well as the light effects, recalls Romantic landscape painting in the tradition of Claude Lorrain (1600–1682)[

embodies the principle of a landscape composed of nature and architecture.32 The portrayal exhibits both features of European Romantic landscape painting and the "observational pathos" of the Enlightenment, which is connected to the image's status as a witness. The portal to the cella, which Cassas portrayed in several attentive and true-to-detail architectural studies, is depicted as an ancient ruin overgrown with lush, fanciful vegetation. The distinctive feature of the temple (built 120 AD) is the keystone of the architrave, which slipped down during an earthquake in 1795. In his watercolour, Cassas exaggerated the displacement caused by the earthquake, depicting the entire wall as unstable. In addition, he slid the keystone towards the viewer, such that the sculptural detail of the soffit, a bird with outspread wings, is infused with drama. Travellers identified this image as an eagle, thus leading the temple to be identified as a Temple of Jupiter. The monumental portal presents itself to the viewer like an open window that gives a view onto a landscape with ancient ruins glittering in the distance. The theme of the ruins and their placement in nature, as well as the light effects, recalls Romantic landscape painting in the tradition of Claude Lorrain (1600–1682)[ ]. The Oriental figures in the foreground who make up part of the staffage betoken the "Oriental character" of this antiquity.

]. The Oriental figures in the foreground who make up part of the staffage betoken the "Oriental character" of this antiquity.

In contrast to the watercolour, in his etching The portal of the cella of the Temple of Bacchus , the artist opted for a closer perspective and dispensed entirely with the integration of landscape. The ancient ruin stands isolated in the foreground. Yet the drama of the damaged architrave is not entirely absent. In fact, Cassas highlights its precarious balance even further through the close view of the monument. The draughtsman's attention in this rendition is directed entirely to architectural details and to the portal's sculptural decoration, which in 1785 were apparently still quite well preserved.33 The viewer's gaze is led along the pale, Romantic ray of light through the portal to the remaining ruins of the temple. The etching's focus on portraying the ancient monument's architecture is further underscored by the scene in the foreground, where Cassas himself is among the figures. He sits on a slab, dressed in Oriental garb, observed by the Oriental locals while he sketches the structure.34 Cassas portrays himself in this folio as a travelling artist whose pictures are the result of his own experiences on site. Emblematic of the Enlightenment, the written memorialization of the journey is accompanied by the witness of drawings – text and image become means to the acquisition of knowledge. The insertion of self-portraits is common in reports of travels to far-off lands;35 it served increasingly as a means of attesting to the authenticity of the unknown and the novel.

, the artist opted for a closer perspective and dispensed entirely with the integration of landscape. The ancient ruin stands isolated in the foreground. Yet the drama of the damaged architrave is not entirely absent. In fact, Cassas highlights its precarious balance even further through the close view of the monument. The draughtsman's attention in this rendition is directed entirely to architectural details and to the portal's sculptural decoration, which in 1785 were apparently still quite well preserved.33 The viewer's gaze is led along the pale, Romantic ray of light through the portal to the remaining ruins of the temple. The etching's focus on portraying the ancient monument's architecture is further underscored by the scene in the foreground, where Cassas himself is among the figures. He sits on a slab, dressed in Oriental garb, observed by the Oriental locals while he sketches the structure.34 Cassas portrays himself in this folio as a travelling artist whose pictures are the result of his own experiences on site. Emblematic of the Enlightenment, the written memorialization of the journey is accompanied by the witness of drawings – text and image become means to the acquisition of knowledge. The insertion of self-portraits is common in reports of travels to far-off lands;35 it served increasingly as a means of attesting to the authenticity of the unknown and the novel.

The device of self-portrayal is elaborated further in the drawing Absalom's tomb . On the left side is a scene containing a self-portrait of Cassas: standing on a buttress, measuring stick in hand and supported by an assistant, he measures the monument. In this self-portrayal – like in the passage from the letter quoted above – the artist combines the work of the draughtsman with that of the modern scientist who gathers his data from direct observation. It is interesting to observe how the standards that were slowly gaining credence for scientific work (data collection, measuring, drawing) also took shape in the distant, foreign sites of Oriental antiquity. And this is the case both for the literary form of the travelogue and for images, most of which stood independently. Both were responsible for the transfer of newly won knowledge to the West.

. On the left side is a scene containing a self-portrait of Cassas: standing on a buttress, measuring stick in hand and supported by an assistant, he measures the monument. In this self-portrayal – like in the passage from the letter quoted above – the artist combines the work of the draughtsman with that of the modern scientist who gathers his data from direct observation. It is interesting to observe how the standards that were slowly gaining credence for scientific work (data collection, measuring, drawing) also took shape in the distant, foreign sites of Oriental antiquity. And this is the case both for the literary form of the travelogue and for images, most of which stood independently. Both were responsible for the transfer of newly won knowledge to the West.

A midpoint summary can be formulated as follows: the observational pathos of the Enlightenment did not lead directly to the exact reproduction of reality or an empiricization of images from artist journeys; rather there is a tension between the generic demands of painting and the immediacy of visual impression. Attention to the genesis and comparison of images indicates that the "true" or "authentic" image is no neutral or eternal entity. Instead, the new requirements for images attest to the latter's embedding in the interests of the Enlightenment and in those of the budding cultures of science and their criteria for classification and knowledge.36

Cassas' conception of images thus stands at the intersection of various representational traditions that – as we shall see below – were taken up and developed further on expeditions to the Orient at the turn of the nineteenth century. In the depiction of the Sphinx or in the watercolour of the Temple of Bacchus, the Oriental landscape becomes a historically mediated place. Here one sees the traditions of the educated bourgeois travel-picture, in which the topographical embedding of historical attractions emphasizes that the portrayed image is the result of the artist's own first-hand impressions and authentic experiences. The portrayal of light and clouds corresponds to the conventions of Romantic, picturesque landscape depiction. The true-to-detail drawing of the Pyramid's construction, the documentation of the traces of destruction on the neck of the Sphinx and the etching of the Temple of Bacchus all evince explicitly novel tendencies in artistic representation. They point toward the kind of empirically oriented portrayal that characterizes the early-nineteenth-century Description de l'Égypte. This work will be the focus of the following observations. The innovations in artistic representation that now took place in the context of scientifically oriented expeditions can be traced under the following rubrics: detail work, attention to the quotidian and the investigation of things on the margins of what was already known.

The Description de l'Égypte and on-site scientific archaeology

The interest in Egypt and the Orient that was ignited by journeys like Cassas's and especially by his images attained a new character with the Description de l'Égypte (Description of Egypt) commissioned by Napoleon I (1769–1821)[ ]. This character can be seen, on the one hand, in the demand for a comprehensive and complete survey of the country (in which are reflected the ideals of the Encyclopédie), and on the other hand in the practical example of a scientific expedition commissioned by the state and conducted in concert with newly founded institutions (for example the Institut d'Égypte, founded specifically for that purpose in 1798).37 Here we see, in the epoch in which the modern sciences developed, a noteworthy interplay between scientific and colonial interests, between science and art.

]. This character can be seen, on the one hand, in the demand for a comprehensive and complete survey of the country (in which are reflected the ideals of the Encyclopédie), and on the other hand in the practical example of a scientific expedition commissioned by the state and conducted in concert with newly founded institutions (for example the Institut d'Égypte, founded specifically for that purpose in 1798).37 Here we see, in the epoch in which the modern sciences developed, a noteworthy interplay between scientific and colonial interests, between science and art.

The work was begun during Napoleon's Egyptian campaign in 1798/1799. The expansionist colonial undertaking failed, but France secured, with its Commission des Sciences et des Arts, made up of over 160 scientists and draughtsmen, an enduring cultural transfer that amounted to a scientific "occupation" of the Orient. The upshot of this common effort of artists and scientists – a kind of compensation for the failed military operation – is the Description de l'Égypte. The French troops were defeated in Egypt by the British in 1801 and had to leave the country. What remained and could be transported back to France was the achievement of the scientific expedition. Among the ca. 35,000 soldiers sent to Egypt were members of France's cultural and scientific elite, who, under the aegis of the Commission des Sciences et des Arts, were to gather information about Egypt. The Commission was composed of over 150 scientists and experts, including mathematicians, engineers, naturalists, architects, draughtsmen, scholars, and compositors. Their illustrated observations were documented in the Description's multi-volume text and picture collection, which, among other things, laid the foundation for the later field of Egyptology.38 This monumental work provides a comprehensive encyclopaedic survey of Egypt, ranging from ancient monuments to botany and geography to descriptions of morals and customs. The drawings executed on site, which were reproduced in the Description as engravings, comprised a compendium of images that included all the types of visual material that would go on to play a role in the history of the pictorial representation of the Orient and the circulation of knowledge that it achieved.

The title page of the Description acts as a visual introduction to the structure of the larger undertaking . With an architectural border as a frame and the depiction of the portal to an Egyptian temple, the page becomes a picture within a picture.39 As if through an open gate or window, the view of an imaginary Nile landscape materializes. A closer look reveals the monuments of ancient Egyptian culture, emblematically condensed, along the banks of the Nile. There is a hoard of archaeological trophies in the foreground, including the ram-headed sphinxes of Karnak, behind it to the right the rosetta stone, and in the middle of the interior picture the head of the Sphinx of Giza. Sketched long the course of the river, which at the same time marks the course of Napoleon's conquests from north to south, are first the obelisk of Alexandria (also called Cleopatra's Needle), then the Dendera temple complex, and on the horizon Trajan's Kiosk with the Temple of Isis in Philae. The island of Philae in the Nile also marks the southernmost point reached by the French invasion. The perspective inscribed in the frontispiece, which plots the monuments of ancient Egypt along the path of the French invasion from north to south, is elaborated further in the classicizing frieze of the gate's architecture within which it is framed. The middle of the upper beam depicts Napoleon in his chariot driving the Mamluks, shrinking before him, out of Egypt. He is pursued from behind by female personifications of the arts and sciences, whereas the lower beam shows the conquered peoples of Egypt offering tribute to the French emperor, signified by the letter "N." The lateral beams feature trophies with the names of the battles won by France.

. With an architectural border as a frame and the depiction of the portal to an Egyptian temple, the page becomes a picture within a picture.39 As if through an open gate or window, the view of an imaginary Nile landscape materializes. A closer look reveals the monuments of ancient Egyptian culture, emblematically condensed, along the banks of the Nile. There is a hoard of archaeological trophies in the foreground, including the ram-headed sphinxes of Karnak, behind it to the right the rosetta stone, and in the middle of the interior picture the head of the Sphinx of Giza. Sketched long the course of the river, which at the same time marks the course of Napoleon's conquests from north to south, are first the obelisk of Alexandria (also called Cleopatra's Needle), then the Dendera temple complex, and on the horizon Trajan's Kiosk with the Temple of Isis in Philae. The island of Philae in the Nile also marks the southernmost point reached by the French invasion. The perspective inscribed in the frontispiece, which plots the monuments of ancient Egypt along the path of the French invasion from north to south, is elaborated further in the classicizing frieze of the gate's architecture within which it is framed. The middle of the upper beam depicts Napoleon in his chariot driving the Mamluks, shrinking before him, out of Egypt. He is pursued from behind by female personifications of the arts and sciences, whereas the lower beam shows the conquered peoples of Egypt offering tribute to the French emperor, signified by the letter "N." The lateral beams feature trophies with the names of the battles won by France.

The prominent significance of the title page is already announced by its placement at the beginning of the work. Its visual design is conceived as an eye-catcher at the outset of the complete opus, but it also functions metaphorically as an introduction to reading the following 21 volumes, in which the entire undertaking unfolds.40 The visual composition of the page announces the self-understanding of Napoleon's Egyptian expedition: the military operation is conceived as a civilizing mission in which Napoleon, in the company of the sciences and the arts, "liberates" ancient Egyptian high culture after centuries of Mamluk and Ottoman rule. The full title emphasizes neutral description, the compilation of a collection of observations and research; the progress metaphor of the Enlightenment is discernable.41 Had the invasion been militarily successful, the massive quantity of information would have provided the logistical foundation for the construction of a French colonial empire. Accordingly, the collection communicated the sense, developed across the individual volumes, of Egypt as a largely untapped scientific resource. Hence a survey was in order, to be conducted in line with the modern scientific understanding then taking shape, based firmly on precise observation and documentation. In the particular case of the Description, colonialism and knowledge transfer worked hand in hand; or rather, the scientific and artistic product compensates for the unsuccessful military conquest and occupation of Egypt.

The volume on Memphis, including the monuments of Giza, appeared in 1822.42 It contains several plates depicting the Sphinx and the pyramids. One engraving in particular shows the subject in a way that is reminiscent in several ways of Cassas's Vue de la tête colossale du Sphinx (see above). The head of the Sphinx, which is buried up to its neck in sand, towers monumentally above the archaeological site and occupies the left side of the image. The Great Pyramid and its smaller satellites provide the background. The draughtsman clearly directs the viewer's gaze to the Sphinx's head and the condition of its surface: the mutilation of the nose; the erosion of the stone thanks to climate and time, which have left their traces on the face and neck; he even draws in the eyes, giving the Sphinx a lifelike quality. When the Description's engraving is compared with Cassas's watercolour, one sees – despite the autopsy of the on-site report – the high degree of illusion in the visual evocation of this ancient monument. The two images differ above all in their portrayals of the destruction of the face. Cassas's fictive, imaginary completion goes so far that the Sphinx's features are fully reconstructed, whereas the Description's engraving turns the destruction itself into the main feature of the depiction. Neither image, however, dispenses with the light and shadows that give the monument a mysterious presence. The Description's manner of representation goes further in its emphatically realistic style of drawing and the related portrayal of the archaeological work. The Sphinx seems to have be unearthed thanks only to the excavation. The foreground presents to the viewer a plateau that has been created by the excavation – clearly discernable from the sand mounds in the middle ground. Miniature-like forms of local assistants dot the excavation site in the shadow of the Sphinx. In the lower right corner of the picture, a Napoleonesque figure points to the Sphinx. These narrative elements, reminiscent of landscape staffage, show how the conditions of cultural transfer have changed with the Description. European travel culture now being continued in the form of scientific expeditions organized by the military, the tone for the depiction of the travel scene and the attendant experience with foreignness is set not by the staging of an exotic staffage with Orientals encamped before ancient ruins, but rather by personnel from science and politics. In addition, the Napoleonesque figure in front of the ancient monument documents the colonial presence and the scientific occupation of the Orient in the form of the Description.

in a way that is reminiscent in several ways of Cassas's Vue de la tête colossale du Sphinx (see above). The head of the Sphinx, which is buried up to its neck in sand, towers monumentally above the archaeological site and occupies the left side of the image. The Great Pyramid and its smaller satellites provide the background. The draughtsman clearly directs the viewer's gaze to the Sphinx's head and the condition of its surface: the mutilation of the nose; the erosion of the stone thanks to climate and time, which have left their traces on the face and neck; he even draws in the eyes, giving the Sphinx a lifelike quality. When the Description's engraving is compared with Cassas's watercolour, one sees – despite the autopsy of the on-site report – the high degree of illusion in the visual evocation of this ancient monument. The two images differ above all in their portrayals of the destruction of the face. Cassas's fictive, imaginary completion goes so far that the Sphinx's features are fully reconstructed, whereas the Description's engraving turns the destruction itself into the main feature of the depiction. Neither image, however, dispenses with the light and shadows that give the monument a mysterious presence. The Description's manner of representation goes further in its emphatically realistic style of drawing and the related portrayal of the archaeological work. The Sphinx seems to have be unearthed thanks only to the excavation. The foreground presents to the viewer a plateau that has been created by the excavation – clearly discernable from the sand mounds in the middle ground. Miniature-like forms of local assistants dot the excavation site in the shadow of the Sphinx. In the lower right corner of the picture, a Napoleonesque figure points to the Sphinx. These narrative elements, reminiscent of landscape staffage, show how the conditions of cultural transfer have changed with the Description. European travel culture now being continued in the form of scientific expeditions organized by the military, the tone for the depiction of the travel scene and the attendant experience with foreignness is set not by the staging of an exotic staffage with Orientals encamped before ancient ruins, but rather by personnel from science and politics. In addition, the Napoleonesque figure in front of the ancient monument documents the colonial presence and the scientific occupation of the Orient in the form of the Description.

Napoleon's archaeological program – the observation, measuring and drawing – and the participants on the expedition can be seen in many other of the Description's engravings. Let it suffice to cite two examples. One is another portrayal of the Pyramids and Sphinx from the fifth volume , and the other is a view of the Colossus of Thebes in Karnak in the third volume on ancient Egypt

, and the other is a view of the Colossus of Thebes in Karnak in the third volume on ancient Egypt .43 The assistants portrayed in these images act as measuring sticks to immediately illustrate the scale to viewers at home, but they also serve to recall the expedition and its scientific work on the ancient monuments. Thus emerges an iconography of the "scientific drawing" as part of a scientific expedition. After the Voyage pittoresque, which grew out of the Grand Tour, now these new forms of artistic representation, under the auspices of science and colonialism, organized the transfer of knowledge from the Orient.

.43 The assistants portrayed in these images act as measuring sticks to immediately illustrate the scale to viewers at home, but they also serve to recall the expedition and its scientific work on the ancient monuments. Thus emerges an iconography of the "scientific drawing" as part of a scientific expedition. After the Voyage pittoresque, which grew out of the Grand Tour, now these new forms of artistic representation, under the auspices of science and colonialism, organized the transfer of knowledge from the Orient.

Hildegard Frübis

Appendix

Sources

Description de l'Égypte: Publiée par les ordres de Napoléon Bonaparte. Konzeption und Text von Gilles Néret, Köln et al. 2007.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von: Italienische Reise, Dritter Teil. Goethes Werke in 10 Bänden, ausgewählt von Peter Boerner, Zürich 1962, vol. 9.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von: Goethe's travels in Italy, together with his second residence in Rome and fragments on Italy, translation Charles Nisbet, London 1885.

Houel, Jean-Pierre-Louis-Laurent: Voyage pittoresque des isles de Sicile, de Malte et de Lipari : où l'on traite des antiquités qui s'y trouvent encore, des principaux phénomènes que la nature y offre, du costume des habitans, et de quelques usages, Paris 1782–1787. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k107640b [2024-05-02].

Jomard, Edme François (ed.): Description de l'Égypte, ou recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l'expédition de l'armée française, publié par les ordres de Sa Majesté l'Empereur Napoléon le Grand. 20 vols. Paris 1809–1828. URL: https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb333411490 [2021-08-11]

Néret, Gilles (ed.): Description de l'Égypte, Köln et al. 2007.

Norden, Fredeik Ludvig: Voyage d'Égypte et de Nubie, Paris 1795–1798. URL: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6213604m [2024-05-02]; vol. 2: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k62136051 [2024-05-02].

Pococke, Richard: Voyages de Richard Pockocke: en orient, dans l'Egypte, l'Arabie, la Palestine, la Syrie, la Grèce, la Thrace, etc; trad. de l'anglois par une société de gens de lettres [par de La Flotte] Paris 1772/1773. URL: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1062162 [2024-05-02].

Savary, Claude: Lettres sur l'Egypte, Paris 1785/1786.

Volney, Constantin-François de: Voyage en Syrie et en Égypte, pendant les années 1783, 1784 et 1785, Paris 1787. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1041132 [2024-05-02].

Literature

Bopp, Petra et al. (eds.): Mit dem Auge des Touristen: Zur Geschichte des Reisebildes: Eine Ausstellung des Kunsthistorischen Instituts der Universität Tübingen in der Kunsthalle Tübingen vom 22. August bis 20. September 1981, Tübingen 1981.

Bopp, Petra: Die touristische Kolonisierung des Orients, in: Petra Bopp et al. (eds): Mit dem Auge des Touristen: Zur Geschichte des Reisebildes: Eine Ausstellung des Kunsthistorischen Instituts der Universität Tübingen in der Kunsthalle Tübingen vom 22. August bis 20. September 1981, Tübingen 1981, pp. 120–126.

Boerlin-Brodbeck, Yvonne: Caspar Wolf (1735–1783): Landschaft im Vorfeld der Romantik: Katalog zur Ausstellung, 15. Juni – 14. September 1980, Basel 1980.

Daston, Lorraine / Galison, Peter: The Image of Objectivity, in: Representations 40 (1992), pp. 81–128. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/2928741 / URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2928741 [2021-08-11]

Daston, Lorraine / Galison, Peter: Objektivität, Frankfurt am Main 2007.

Dürbeck, Gabriele et al. (eds.): Wahrnehmung der Natur, Natur der Wahrnehmung: Studien zur Geschichte visueller Kultur um 1800, Dresden 2001.

Estelmann, Frank: Sphinx aus Papier: Ägypten im französischen Reisebericht von der Aufklärung bis zum Symbolismus, Heidelberg 2006.

Frübis, Hildegard: Die Wirklichkeit des Fremden: Die Darstellung der Neuen Welt im 16. Jahrhundert, Berlin 1995.

Gilet, Annie (ed.): Louis-François Cassas 1756–1827: Dessinateur-Voyageur: Im Banne der Sphinx: Ein französischer Zeichner reist nach Italien und in den Orient: 22. April–19. Juni 1994, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Graphische Sammlung Köln, Mainz et al. 1994.

Gillispie, Charles Coulston: Historical Introduction, in: Charles Coulston Gillispie et al. (eds.): Monuments of Egypt: The Napoleonic Edition: The Complete Archaeological Plates from La Description de l'Égypte, Princeton, NJ 1987, pp. 1–39.

Grinevald, Paul-Marie: Description de l'Égypte: Bilan scientifique d'une expédition militaire: Exposition, Paris, Cour de cassation, 8 au 28 juin 1995, Paris 1995.

Haas, Mechthild (ed.): Orient auf Papier: Von Louis-Francois Cassas bis Eugen Bracht: Graphische Sammlung, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, anlässlich der gleichnamigen Ausstellung vom 25. August bis 10. November 2002, Mainz 2002.

Haldemann, Anita et al.: Caspar Wolf – Gipfelstürmer zwischen Aufklärung und Romantik: Museum Kunst Palast, Düsseldorf, 26. September 2009 bis 10. Januar 2010, Düsseldorf 2009.

Howoldt, Jenns E. et al. (eds.): Expedition Kunst: Die Entdeckung der Natur von C. D. Friedrich bis Humboldt: Katalog zur Ausstellung vom 25. Oktober 2002 bis 23. Februar 2003 in der Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg et al. 2002.

Keller, Susanne B.: Gipfelstürmer, Künstler und Wissenschaftler auf der Suche nach dem Überblick, in: Jenns E. Howoldt et al. (eds.): Expedition Kunst: Die Entdeckung der Natur von C. D. Friedrich bis Humboldt: Katalog zur Ausstellung … vom 25. Oktober 2002 bis 23. Februar 2003 in der Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg et al. 2002, pp. 27–36.

Keller, Susanne B.: Naturgewalt im Bild: Strategien visueller Naturaneignung in Kunst und Wissenschaft 1750–1830, Weimar 2006.

Nowel, Ingrid: Die Geschichte der Ägyptenreisen seit dem 16. Jahrhundert, in: Ingrid Nowel (ed.): Giovanni Belzoni: Entdeckungsreisen in Ägypten 1815–1819, Köln 1982, pp. 220–277.

Plagemann, Volker: Von der Pilgerfahrt zur "Reise ins Licht": Künstlerreisen nach Italien, in: Hermann Arnhold (ed.): Orte der Sehnsucht: Mit Künstlern auf Reisen: Anlässlich der Ausstellung im LWL-Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Münster, vom 28. September 2008 bis zum 11. Januar 2009, Münster 2008, pp. 36–45.

Prochaska, David: Art of Colonialism, Colonialism of Art: The Description de l'Égypte (1809–1828), in: L'Esprit Créateur 34, 2 (1994), pp. 69–91. URL: https://doi.org/10.1353/esp.1994.0057 / URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26287498 [2021-08-11]

Sievernich, Gereon et al. (eds.): Europa und der Orient 800–1900: 28. Mai–27. August 1989: Eine Ausstellung des 4. Festivals der Weltkulturen Horizonte '89 im Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, Gütersloh et al. 1989.

White, Christopher: Die Grand Tour, in: John Gage (ed.): Zwei Jahrhunderte englische Malerei: Britische Kunst und Europa 1680–1880: Haus der Kunst München, 21. November 1979 bis 27. Januar 1980, München 1979, pp. 163–216.

Wuthenow, Ralph Rainer: Die erfahrene Welt: Europäische Reiseliteratur im Zeitalter der Aufklärung, Frankfurt am Main 1980.

Notes

- ^ Bopp, Mit dem Auge 1981, p. 8: "bildeten sich in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts ganz anders motivierte Reisen heraus. Neben dem aufklärerischen Interesse an gesellschaftlichen Zuständen fremder Länder zielte forschende Neugier in bislang unbekannte, nicht kultivierte Gegenden" (translation K. G.-B.).

- ^ Keller, Gipfelstürmer 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Boerlin-Brodbeck, Caspar Wolf 1980; Haldemann, Caspar Wolf 2009.

- ^ See Bopp, Mit dem Auge 1981, pp. 7f.; Plagemann, Von der Pilgerfahrt 2008, pp. 36–44.

- ^ Bopp, Mit dem Auge 1981, p. 8.

- ^ See the exhibition catalogue Howoldt, Expedition Kunst 2002, especially the contribution by Keller, Gipfelstürmer 2002.

- ^ Keller, Gipfelstürmer 2003, p. 27.

- ^ See Nowel, Die Geschichte 1982, pp. 221ff.; Estelmann, Spinx 2006, ch. 2; Haas, Orient auf Papier 2002, pp. 9–14.

- ^ In addition, there was the artistic engagement with Egypt, whose centre was in Rome and which assembled collections of "original objects." The first public collection of Egyptian and Egyptianizing art opened in the Capitoline Museum in 1748; important private collections of the age were, for example, those of Cardinal Alessandro Albani (1692–1779) and the Borghese family.

- ^ Goethe, Italienische Reise 1962, p. 502: "Ein französischer Architekt, mit Namen Cassas, kam von seiner Reise in den Orient zurück; er hatte die wichtigsten alten Monumente, besonders die noch nicht herausgegebenen gemessen, auch die Gegenden, wie sie anzuschauen sind, gezeichnet nicht weniger alte zerfallene und zerstört Zustände bildlich wieder hergestellt und einen Teil seiner Zeichnungen, von großer Präzision und Geschmack, mit der Feder umrissen und, mit Aquarellfarben belebt, dem Auge dargestellt" (translation Charles Nisbet, in: Goethe, Goethe's travels, 414).

- ^ In 1784 he accompanied Choiseul-Gouffier to Constantinople and was commissioned by him to journey to Greece (1784–1787). On this journey he produced sketches that illustrated the second volume of Voyage pittoresque de la Grèce, which was published by Choiseul-Gouffier in 1809.

- ^ On this point, see the detailed treatment in: Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994.

- ^ This undertaking fell into competition with its successor, the Description de l'Égypte, whose intention, number of participants and institutional framework represent a new dimension in the history of travel.

- ^ Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994, p. 107.

- ^ Constantin-François Chassebœuf, comte de Volney summed up his Egyptian journey in a travelogue entitled Les Ruines ou Méditation sur les Révolutions des Empires (1791), therewith originating the cult of Egypt's cultural remains.

- ^ At the time of its publication in 1789, the portfolio must have contained more than 1000 drawings and engravings. See Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994, p. 108.

- ^ Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994, p. 108.

- ^ Haas, Orient auf Papier 2002, p. 26: "Inkunabeln der europäischen Ägyptenträume" (translation K. G.-B.).

- ^ The face appears fully reconstructed but is nevertheless "depicted slightly more destroyed that it was in 1785" ("einen Deut zerstörter wiedergegeben als es 1785 war"; translation K. G.-B.); see Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994, p. 193.

- ^ Research into the art of the pharaohs was still in its infancy; thus, although the monuments were becoming increasingly familiar, there was still room for speculative – and in part mystifying - interpretations. Vivification is also found in the drawing of an anonymous artist with the initials F. D. S. at the end of the eighteenth century: "The artist gave pupils to the eyes that Cassas had left sightless, such that the figure opens its eyes melancholically and directs its gaze up and to the right. In this way, the head, rendered in three-quarter profile, seems to be turning" ("[D]er Künstler hat die bei Cassas blicklosen Augen mit Pupillen versehen, so dass die Figur in melancholischem den Blick nach rechts oben richtet. Dadurch scheint der im Dreiviertelprofil wiedergegebene Kopf in eine reale Drehbewegung versetzt zu werden"; translation K. G.-B.). Haas, Orient auf Papier 2002, p. 28.

- ^ Haas, Orient auf Papier 2002, p. 10.

- ^ The monument measures 73.50 m long and 20 m high; it was already restored several times in antiquity, only to be subjected again to sandstorms. The entire sculpture was first excavated and liberated from debris and sand between 1925 and 1932.

- ^ Norden, Voyage d'Égypte et de Nubie 1795/1798.

- ^ Pococke, Voyages de Richard Pockocke 1772/1773.

- ^ There were also two reports by contemporaries that he probably knew: Savary, Lettres sur l'Egypte 1785/1786, and Volney, Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte, 1787(Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994, p. 186).

- ^ Towards the end of the eighteenth century, small series of topographical views of Egypt appeared, giving shape to the canon of attractions: The Sphinx of Giza, the pyramids, Pompey's Pillar in Alexandria, and views of obelisks and pyramids on the banks of the Nile. Among these are the small-format drawings – seeming to anticipate the postcard format – of the anonymous French artist with the initials F. D. S. and those of the English artist known by the initials B. S. See Haas, Orient auf Papier 2002, pp. 28ff.; Bopp, Mit dem Auge 1981.

- ^ See also Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994, p. 186.

- ^ Houel, Voyage pittoresque 1782.

- ^ See Keller, Naturgewalt 2006.

- ^ See Howoldt, Expedition Kunst 2002; for detailed information on Hoüel, see Keller, Naturgewalt 2006, pp. 188–248; for Hamilton, see Keller, Naturgewalt 2006, pp. 249ff.

- ^ Letter to the ambassador, Bscherre, 21 July 1785, Bibliothèque Nationale, Départment des Manuscrits, Fol. 60 n.a. Fr. 7558. Cited in Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994, p. 159: "...[I]ch hatte dort ziemliche Ruhe. Ich habe die wichtigsten Bauwerke gezeichnet und vermessen, die den schönen Altertümern in Rom an Großartigkeit, Adel und architektonischer Reinheit in nichts nachstehen" (translation K. G.-B.).

- ^ None of the drawings made on site at the ostensible Temple of Jupiter, on which this image is based, are extant; six plates depicting the structure were engraved for the publication, based on 20 preparatory drawings. See Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994, p. 159.

- ^ Gilet, Louis-François Cassas 1994, p. 160.

- ^ It is said that Cassas wore local clothing on his travels in order to protect himself from thieves and marauders, but also to assimilate, at least in appearance, to the local population (see Sievernich, Europa und der Orient 1989, p. 280).

- ^ This can be seen especially well in the reports and illustrations of the voyages of discovery to the "New World" in the sixteenth century (see Frübis, Die Wirklichkeit 1995); literary scholarship has pointed out the construction of the sensitive, Enlightenment subject and the connection between autobiography and travelogue in the works of Bougainville, Forster and Cook (see Wuthenow, Die erfahrene Welt 1980, p. 11).

- ^ On this point, see Daston / Galison, The Image 1992 and Daston / Galison, Objektivität 2007. Their works deal especially with scientific atlases (botany, medicine) and their illustrations. Such sources also evince the development of concepts like "the truth of nature" and "objectivity."

- ^ The Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers was edited by Denis Diderot and Jean Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert. It contains articles by 142 authors collectively called the Encyclopaedists. The first volume appeared in 1751. The Encyclopédie is one of the major works of the Enlightenment and is infused with its foundational ideal of collecting the knowledge of all time and making it available to the world.

- ^ The publication was commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte and published by the Commission d'Égypte under the direction of Claude-Louis Berthollet (1748–1822) and the editor Edmé-François Jomard (1777–1862) between 1809 and 1828. It included nine volumes of text and eleven folio picture volumes, illustrated with a total of 837 engravings. This publication information is drawn from the edition of Gilles Néret, Description de L'Égypte 2007, p. 19, where a selection of the illustrations is reprinted. On the work, see also: Gillispie, Historical Introduction 1987; Grinevald, Description de l'Égypte 1995; Prochaska, Art of Colonialism 1994.

- ^ On the interpretation of the title page, see also Ulz 2008, pp. 21f. For the more precise identification of the gate, she cites the plate Thébes in the Description.

- ^ On the function of title pages, see Christadler 2004, pp. 47–93. Considered in the light of the discovery of America and the multi-volume America series, a collection of travel reports and illustrations issued by Theodor de Bry (1528–1598), exciting, new connections appear for the Description. De Bry began each of his books with a visually metaphorical title page. He usually used elements of architectural design, especially portals. With regard to the metaphorical function of title pages, Christadler cites the Italian engraver Enea Vico. As early as the middle of the sixteenth century, Vico provided an introduction to reading title pages in his Augustarum Imagines. There the author compares the borders of frontispieces with frames or portals and calls them the gates through which the reader enters the edifice of the book.

- ^ "Description de l'Égypte, ou recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l'expédition de l'armée française, publié par les ordres de Sa Majesté l'Empereur Napoléon le Grand."

- ^ Antiquités, volume V, Pyramides de Memphis.

- ^ Vue générale des pyramides et du sphinx, prise au soleil couchant, Antiquités, volume V, pl. 8; Vue d'un colosse placé á l'entrée de la salle hypostyle du palais, volume III, pl. 20.