Introduction

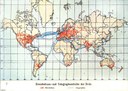

During the period from the 1870s until the outbreak of the First World War, Western imperialism was at its zenith. The idea of a Western civilising mission in other parts of the world, grounded in technological progress and moral as well as cultural advancement, served as one of the building blocks of imperialism.1 This notion of superiority, however, had a reverse to which it was attached in a dialectical relationship: the insecurity of the imperialists and their fear of the subjugated and colonised peoples.2 One of the guises in which this anxiety appeared was the idea of the "Yellow Peril" (alternatively "yellow menace" or "yellow spectre"). This rhetorical figure claimed that Europe and North America were somehow under threat from the peoples of East Asia, which had been contained by means of unequal treaties since the 1840s. So far, "Yellow Peril" has usually been analysed as a catchphrase informing political and social debates.3 As such, it is viewed as a more or less continuous trope that originated in the United States in the 1870s, spilled over into Europe (where it was prefigured by discussions of the supposed Russian or American menaces) in the 1890s and continued up until the First World War, into the inter-war period and beyond. In my essay, I shall build on this research but will link the Yellow Peril discourse4 to three media events: the Boxer War of 1898–1901 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904/1905.

The "Yellow Peril" between discourse and media event

The Yellow Peril discourse comprised several strands.5 Before 1905, it concentrated mainly on economics and the long-term effects of imperialism. It argued that the imperialist framework might create profits from overseas markets in the short run but would lead to the industrialisation of Japan and China in the long run. The consequence would be economic competition to Western economies. This had practical consequences. In 1896 and 1897, Britain, the United States and the German Reich each dispatched a commission to East Asia to study the local economic conditions; in all three cases, their reports emphasised the tangible benefits rather than the potential dangers of Western economic engagement.6 The fear of economic competition and that of East Asian (in particular Chinese) labour migration clearly went hand in hand, evoking the spectre of cheap Chinese workers out-competing their counterparts in North America and Europe. It was this vision that first gave rise to the phrase "Yellow Peril" in the United States, particularly in California. Resistance to Chinese immigration forced US political institutions to react by passing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which severely curtailed Chinese labour migration .7 The fear of Chinese labour competition spread into Europe, occasionally fuelled by concrete initiatives. For example, local administrators and landowners' associations in West Prussia repeatedly suggested recruiting Chinese agricultural labourers in the 1890s and 1900s, as the available labour force was scarce. The idea sparked a controversy in which social and cultural stereotypes were mustered against the importation of Chinese labour.8 In fact, the German Social Democratic Party had warned against competition from Chinese labour and used "Yellow Peril" as a catchphrase supposed to convey a more general critique of capitalism. The International Socialist Congresses of the 1900s almost split over the question of whether labour competition from outside Europe should be excluded. The motion was finally rejected in 1907.

.7 The fear of Chinese labour competition spread into Europe, occasionally fuelled by concrete initiatives. For example, local administrators and landowners' associations in West Prussia repeatedly suggested recruiting Chinese agricultural labourers in the 1890s and 1900s, as the available labour force was scarce. The idea sparked a controversy in which social and cultural stereotypes were mustered against the importation of Chinese labour.8 In fact, the German Social Democratic Party had warned against competition from Chinese labour and used "Yellow Peril" as a catchphrase supposed to convey a more general critique of capitalism. The International Socialist Congresses of the 1900s almost split over the question of whether labour competition from outside Europe should be excluded. The motion was finally rejected in 1907.

Besides issues of economic development, there was also a political dimension to the Yellow Peril, as East Asia was primarily perceived as a political and military threat to Europe and North America. At one end of the political spectrum, anti-imperialists such as Johann von Bloch (1836–1902) and Hermann von Samson-Himmelstjerna (1826–1908) held imperialism directly responsible for the emergence of the Yellow Peril, as it had fostered hatred of the West. They considered it necessary to come to terms with the peoples of East Asia. At the other end, the popularity of the "theory of world empires" (Weltreichslehre) invited speculation about a future realignment of global power in which Europe would lose its leading position. In addition to the United States and Russia, East Asia was envisioned as another up-and-coming challenger.9

Looking at the Yellow Peril discourse in the way outlined above means discussing it in terms of a steady and continuous intellectual trajectory. Viewing it as a media event, as this essay does, requires an altogether different approach. Media events are "high holidays of mass communication",10 disrupting the ordinary flow of life and condensations of social discourses or debates;11 they thrive on their (in the literal sense of the term) extra-ordinary character while bringing deeper concerns to the fore. In this sense, the focus must be placed not so much on the steady development of the Yellow Peril discourse itself, but on the ruptures created by the three events that are usually mentioned as its catalysts: the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, the Boxer War of 1900–1901 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. While the former functioned as a prelude of sorts, the two latter were full-blown global media events sustained by a modern and sophisticated technological apparatus. Coverage of the Boxer War rested on the telegraph network that by 1900 spanned the entire globe and to which China had first been connected as early as the 1870s.12 Likewise, Lionel James's (1871–1955) reports from the Russo-Japanese War for The Times were the first wireless transmissions in the history of journalism.13 The relationship between media events and "real" events awaits further clarification; suffice it to say here that although both exhibit the "minimum of 'before' and 'after'" providing "the significant unity that makes an event out of incidents",14 events "on the ground" and in the media are not congruent. As "real" events, all three wars came to a formal conclusion through agreements – albeit imposed – reached in peace negotiations: the treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, the Boxer Protocol of September 1901 and the peace treaty of Portsmouth in 1905. Neither the Boxer Protocol nor the Portsmouth treaty put a stop to the media coverage of the war, however; especially the case of the Boxer War, publications continued in the wake of the peace settlement. This was particularly true of the book market in the West, which was now swamped with eyewitness accounts from participants, be they soldiers or missionaries.15

and to which China had first been connected as early as the 1870s.12 Likewise, Lionel James's (1871–1955) reports from the Russo-Japanese War for The Times were the first wireless transmissions in the history of journalism.13 The relationship between media events and "real" events awaits further clarification; suffice it to say here that although both exhibit the "minimum of 'before' and 'after'" providing "the significant unity that makes an event out of incidents",14 events "on the ground" and in the media are not congruent. As "real" events, all three wars came to a formal conclusion through agreements – albeit imposed – reached in peace negotiations: the treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, the Boxer Protocol of September 1901 and the peace treaty of Portsmouth in 1905. Neither the Boxer Protocol nor the Portsmouth treaty put a stop to the media coverage of the war, however; especially the case of the Boxer War, publications continued in the wake of the peace settlement. This was particularly true of the book market in the West, which was now swamped with eyewitness accounts from participants, be they soldiers or missionaries.15

Prelude: The Sino-Japanese War of 1895

Although as a global media event, the first Sino-Japanese War was dwarfed by the two subsequent wars in 1900–1901 and 1904–16

The war between the East Asian island state and its larger continental neighbour undoubtedly marked an important point in Japan's "mimetic imperialism". By this term, the American historian Robert Eskildsen (born 1956) refers to its strategy of emulating Western imperialism, which, he argues, had been part and parcel of the Meiji reforms since their beginning in 1868.17 The government in Tokyo began its imperialistic pursuits by annexing the Ryūkyū Islands, a tributary state of the Chinese Empire, in 1879, renaming them Okinawa prefecture. As a result of the 1894/1895 war, it acquired its first colony, the island of Taiwan. Owing to a combination of formal colonialism and informal rights exercised in China, by the 1890s Japan had successfully demonstrated its status as an equal to the European powers and the USA. Ironically, at the time of its war against China, the Japanese Empire was constrained by the same unequal treaties binding the Imperial government in Beijing. By 1899, however, Japan had negotiated with the European imperialist powers the abrogation of the treaties and as a result regained full sovereignty in 1912.18

It was the peace settlement of 1895 that sparked the rhetoric of the Yellow Peril. Although the British had suggested a diplomatic intervention as early as October 1894, the Western powers did not become involved until the peace negotiations in the Japanese city of Shimonoseki had got underway. They were suspicious of Japan's intention to acquire not only Taiwan, but also the Liaodong peninsula at the southern tip of Manchuria, viewing cessation of the latter as a threat to stability in East Asia. For this reason, Russia orchestrated a joint diplomatic intervention of European powers – Britain stayed aloof, while France and Germany participated –, forcing Japan to withdraw its claim.19

In Europe, the Yellow Peril discourse emerged against the background of a perceived Japanese threat to the status quo. The German Emperor Wilhelm II (1859–1941) played a central role in these debates – not so much because of his exaggerated claims to having coined the phrase,20 but because he conceived the painting "Peoples of Europe, protect your most sacred values!" (Völker Europas, wahrt eure heiligsten Güter) . As the Kaiser explained in a letter to the Czar in September 1895, "[i]t shows the powers of Europe represented by their respective Genii called together by the Arch-Angel Michael – sent from Heaven – to unite in resisting the inroad of Buddhism, heathenism and barbarism for the Defence of the Cross."21 The painting was drafted by the Kaiser and executed by his former painting teacher Hermann Knackfuß (1848–1915). As Philipp Gassert (born 1965) has argued, Wilhelm instrumentalised the idea of a Yellow Peril as part of a diplomatic diversion, to redirect the Russian gaze away from the Reich's eastern border and towards East Asia.22 However, the impact of the Kaiser's intervention went far beyond its immediate context. Despite being almost immediately adapted by satirical magazines critical of the Kaiser and his policies,23 the painting and its concomitant rhetoric became enduring symbols of the Yellow Peril. Beginning with the Boxer War in 1900, they served as points of reference for various parties in subsequent debates.

. As the Kaiser explained in a letter to the Czar in September 1895, "[i]t shows the powers of Europe represented by their respective Genii called together by the Arch-Angel Michael – sent from Heaven – to unite in resisting the inroad of Buddhism, heathenism and barbarism for the Defence of the Cross."21 The painting was drafted by the Kaiser and executed by his former painting teacher Hermann Knackfuß (1848–1915). As Philipp Gassert (born 1965) has argued, Wilhelm instrumentalised the idea of a Yellow Peril as part of a diplomatic diversion, to redirect the Russian gaze away from the Reich's eastern border and towards East Asia.22 However, the impact of the Kaiser's intervention went far beyond its immediate context. Despite being almost immediately adapted by satirical magazines critical of the Kaiser and his policies,23 the painting and its concomitant rhetoric became enduring symbols of the Yellow Peril. Beginning with the Boxer War in 1900, they served as points of reference for various parties in subsequent debates.

The Boxer War (1900–1901) and the threat in/from East Asia

To a far greater extent than the Sino-Japanese War, the Boxer War24 was a media event of global proportions. The intervention of eight states (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia and the United States) in China was driven by a sense of crisis that revealed long-standing anxieties about the purpose and destiny of the Western presence in East Asia. The emergence of the Boxer movement in 1898–1900 and its subsequent support by the Imperial government of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) seemed to mark a dramatic break with the established treaty system by which China had been subjected to European commercial and financial imperialism.25 As Europeans viewed the imperialist order not only in economic terms, but in fact as a civilising mission, it appeared obvious to them to frame the Boxer War in terms of a conflict between civilisation and barbarism.26

was a media event of global proportions. The intervention of eight states (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia and the United States) in China was driven by a sense of crisis that revealed long-standing anxieties about the purpose and destiny of the Western presence in East Asia. The emergence of the Boxer movement in 1898–1900 and its subsequent support by the Imperial government of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) seemed to mark a dramatic break with the established treaty system by which China had been subjected to European commercial and financial imperialism.25 As Europeans viewed the imperialist order not only in economic terms, but in fact as a civilising mission, it appeared obvious to them to frame the Boxer War in terms of a conflict between civilisation and barbarism.26

It is important to note, however, that coverage of the war was not simply dominated by the notion of the Yellow Peril. As the conflict between China and the European powers (as well as the US and Japan) came to a head in the spring and summer of 1900, European daily newspapers and periodicals focused on a number of topics: the threat to the lives of Europeans residing in China, first at the hands of the Boxers and subsequently during the sieges of the European quarters in Beijing and Tianjin; the breahch of international law manifesting itself, above all, in the murder of the German minister Clemens von Ketteler (1853–1900) [

and Tianjin; the breahch of international law manifesting itself, above all, in the murder of the German minister Clemens von Ketteler (1853–1900) [ ] and the Japanese legation secretary Count Sugiyama; and the slow process of relief operations that eventually culminated in the liberation of Tianjin in mid-July and of Beijing in mid-August 1900.27 To a considerable extent, such reporting relied on telegraphic dispatches. When communication with the besieged European communities in China was cut off, reporters frequently resorted to speculations and rumours, culminating in the claim all Europeans in Beijing had been massacred. It took European journalists and audiences a while to realise they had fallen for a hoax.28

] and the Japanese legation secretary Count Sugiyama; and the slow process of relief operations that eventually culminated in the liberation of Tianjin in mid-July and of Beijing in mid-August 1900.27 To a considerable extent, such reporting relied on telegraphic dispatches. When communication with the besieged European communities in China was cut off, reporters frequently resorted to speculations and rumours, culminating in the claim all Europeans in Beijing had been massacred. It took European journalists and audiences a while to realise they had fallen for a hoax.28

After the relief of Beijing , with more correspondents on the ground and more comprehensive information available through detailed letters rather than sparse telegrams, the focus of attention shifted to the conduct of the Allied troops in China. The atrocities committed by them gave rise to a controversial debate about the merits and shortcomings of the multinational intervention and, more generally, of the transnational informal empire in China.29 This controversy spilled over into the political arena and led to fierce debates in parliament, at least in Germany and to a lesser degree in France. Such political controversies relied directly on news reporting and indirectly on soldiers' letters sent home from the Chinese theatre of war and subsequently published in the press. The German journal Vorwärts, the mouthpiece of the Social Democratic Party, systematically gleaned such letters from local papers, as did its French counterpart L'Aurore, albeit less thoroughly.30

, with more correspondents on the ground and more comprehensive information available through detailed letters rather than sparse telegrams, the focus of attention shifted to the conduct of the Allied troops in China. The atrocities committed by them gave rise to a controversial debate about the merits and shortcomings of the multinational intervention and, more generally, of the transnational informal empire in China.29 This controversy spilled over into the political arena and led to fierce debates in parliament, at least in Germany and to a lesser degree in France. Such political controversies relied directly on news reporting and indirectly on soldiers' letters sent home from the Chinese theatre of war and subsequently published in the press. The German journal Vorwärts, the mouthpiece of the Social Democratic Party, systematically gleaned such letters from local papers, as did its French counterpart L'Aurore, albeit less thoroughly.30

To the extent that the Boxer War was a media event, it was centred on the threat to the imperialist framework in China. This, however, had little to do with the arguments generally associated with the Yellow Peril discourse. The main thrust of media coverage was unrelated to the question of economic or labour competition. What remained was the political and military threat – the media generally agreed, however, the threat was in China, not in Europe. Nevertheless, some publications conjured up the sensationalistic vision of a general "upheaval of the yellow world".31 While the Boxers are today recognized as a merely regional movement limited to the North and Northeast of China, to contemporary observers they seemed to foster unrest in other parts of the Empire as well. For example, the French journal La Dépêche reported in mid-July 1900 that "the [Boxer] uprising extends into all provinces of the [Chinese] empire and that new massacres are to be feared, notably at Wen-Chou, Tai Chow, Che Kiang and Che-Fou".32

Although the idea of an all-out war against foreigners in China may have been linked only vaguely to that of a political-military threat presented to Europe by the "yellow races", this connection shows that the Yellow Peril discourse could inform coverage of the Boxer War. For one thing, the former could provide a framework for understanding the latter. In a letter to the editor of The Times, the author argued that "[t]he 'Yellow Peril' seems to have come upon us, not in the external form in which it presented itself to some fervid imaginations, but in China itself."33 The rebellion of the Boxers, he argued, posed not only a threat to the lives of every foreigner in China, but also to the immense capital investments made in the country, constituting an indirect attack on the British economy. Many of the European troops in China seemed to interpret their mission in the same way, and some of these ideas also found their way into the press as the following description of a conversation with French officers by the French war correspondent Gaston Donnet (1867–1908) shows. Himself a firm believer that China was to all intents and purposes an ossified society and culture, he stated:

And all these people are of the same opinion: they all recognize the Yellow Peril, they all persuade themselves that in ten years – possibly less – it will be necessary to begin afresh [to make war on China, T.K.]. See for example, they tell me, the progress that the Chinese army has made since its campaign against Japan in 1895. See the striking example of Japan itself. And what is Japan, if not the extension of China? If the Japanese can have the most up-to-date cannon, why should the Chinese not have them too?34

Moreover, politicians sought to use ideas about the Yellow Peril in discussions of the Boxer War. The most prominent example, once more, was the German Emperor. Wilhelm II's "Hun Speech" (Hunnenrede)[![Hunnenrede IMG Verabschiedung des deutschen Expeditionskorps durch Kaiser Wilhelm II. [Hunnenrede] vor der Einschiffung nach China in Bremerhaven, black-and-white photograph, 1900, unknown photographer; source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1970-068-53 / CC-BY-SA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1970-068-53,_Bremerhaven,_Verabschiedung_des_ostasiatischen_Expeditionskorps.jpg, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en.](./illustrationen/yellow-peril-bilderordner/hunnenrede-img/@@images/image/thumb) ], delivered to German troops departing for China, has somewhat misleadingly been referred to as an iteration of Yellow Peril rhetoric. Though the the Kaiser did exhort his soldiers to wage a relentless campaign of revenge in China, his address, hyperbolic though it may have been, was very much in line with the discourse on civilisation and barbarism.35 Wilhelm did, however, recycle "his" painting Peoples of Europe, copies of which he donated to several troop transports, in an obvious attempt to link the campaign in China with the Yellow Peril.36 Whereas the overtones of this rather weak connection were primarily political and military, the French deputy Paul Henri d'Estournelles de Constant (1852–1924) explicitly linked the Allied intervention with the economic danger posed by China, although what constituted this danger remained rather vague:

], delivered to German troops departing for China, has somewhat misleadingly been referred to as an iteration of Yellow Peril rhetoric. Though the the Kaiser did exhort his soldiers to wage a relentless campaign of revenge in China, his address, hyperbolic though it may have been, was very much in line with the discourse on civilisation and barbarism.35 Wilhelm did, however, recycle "his" painting Peoples of Europe, copies of which he donated to several troop transports, in an obvious attempt to link the campaign in China with the Yellow Peril.36 Whereas the overtones of this rather weak connection were primarily political and military, the French deputy Paul Henri d'Estournelles de Constant (1852–1924) explicitly linked the Allied intervention with the economic danger posed by China, although what constituted this danger remained rather vague:

If this action [of Europe in China] does not succeed in re-establishing order, we will have lost, without benefit, men, money and respect; if, on the contrary, it succeeds in developing China, beware lest the first result of this operation be the increase of our costs and the debasement of our European products, which means social revolution.37

Finally, the events transpiring from China in 1900 and 1901 could serve as a catalyst for more long-term debates on the Yellow Peril. As a media event, the Boxer War did not end – as did the political and military crisis – with the signing of the Boxer Protocol in September 1901. As coverage in the daily press and in periodicals gradually petered out, books on the Boxer War flooded the market, some of which sought to make sense of recent calamities in terms of the Yellow Peril. Other volumes dealt more specifically with the Yellow Peril, but the timing of their publication indicates that they were inspired by the Boxer crisis.

An example of the former is Sir Robert Hart's (1835–1911) These from the Land of Sinim, written in part during the Boxer crisis and published in the year of its formal conclusion. Hart, the Inspector General of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service and a long-time resident in Beijing, had himself been in the siege of the Legation Quarter in the summer of 1900. Regarding the Boxers as Chinese patriots, he took them as proof that "the future will have a 'yellow' question – perhaps a yellow 'peril' – to deal with," which he regarded as nothing less than threatening "the world's future."38 Like many other commentators, he also acknowledged the dangers that an arms build-up in China might entail: "The Boxer patriot of the future will possess the best weapons money can buy, and then the 'Yellow Peril' will be beyond ignoring."39 Hart differed from many of his fellow commentators, however, in the countermeasures he proposed, arguing that a more tactful and equitable treatment of China was the best way to avert any danger that might emanate from the country.40 On the whole, however, European reactions to the Boxer crisis were dwarfed by those to the Russo-Japanese War four years later, the course of which seemed to bring home to Europeans more clearly their apparent vulnerability.

The Russo-Japanese War and the fear of Japan (and, by extension, China)

As a media event, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 was of a different magnitude compared to the international intervention in China four years previously. While the latter had seen fighting between modern, fully equipped armies, attention was at the time focused on the allegedly "primitive" Boxers. It had ended with a resounding strategic victory of Japan, the first time a non-European defeated a European one.41 Besides, in contrast to the Boxer War, sympathies were divided this time. Public opinion in many European states at the time was not well-disposed towards Russia. Even in France, which was officially allied with the Czar and his government, the press seems to have been divided. While some papers and periodicals viewed Russia as Europe's protector from the (Japanese) Yellow Peril, others conjured up the idea of a "Russo-Mongolian bloc" poised for world domination.42

was of a different magnitude compared to the international intervention in China four years previously. While the latter had seen fighting between modern, fully equipped armies, attention was at the time focused on the allegedly "primitive" Boxers. It had ended with a resounding strategic victory of Japan, the first time a non-European defeated a European one.41 Besides, in contrast to the Boxer War, sympathies were divided this time. Public opinion in many European states at the time was not well-disposed towards Russia. Even in France, which was officially allied with the Czar and his government, the press seems to have been divided. While some papers and periodicals viewed Russia as Europe's protector from the (Japanese) Yellow Peril, others conjured up the idea of a "Russo-Mongolian bloc" poised for world domination.42

By contrast, Britain had concluded an alliance with Japan in 1902 and for this reason took a more positive view of the Japanese war effort. This perspective is exemplified by the detailed account of Japan's Fight for Freedom by Herbert Wrigley Wilson (1866–1940), first published in fortnightly instalments between April 1904 and May 1906.43 The serialised publication is also an indication of how quickly the media market responded to the war with customised formats; a similar work was Gaston Donnet's Histoire de la guerre Russo-Japonaise, which appeared on a weekly basis.44 War correspondents and army officers were observing both sides; thus the non-European side – perhaps for the first time – received extensive and sympathetic first-hand coverage. By contrasting Japan's apparent progress against the alleged "half-Asian" autocratic backwardness of Russia, European commentators demonstrated a great deal of complacency. For example, the Revue hebdomadaire published a comment to the effect that "Japan had offered to the world the extraordinary spectacle of a people abandoning a 1,200 year-old civilisation in favour of that of another race".45 The question, however, remained, to what extent this adaptation of European civilisation could be turned against Europe itself, and this issue became the focus of the debate.

As some of the above comments indicate, media coverage of the Russo-Japanese War differed from that of the Boxer War on a number of counts: First, it was more tightly interwoven with the Yellow Peril discourse from early on in the conflict. A second difference concerned the scope of the backlash. Whereas the Boxer War had endangered Europeans in the Qing Empire and China's future rise was at best dimly visible on the horizon, the Russo-Japanese War seemed to signal more imminent dangers to Europe itself. Thirdly, it appears that a far larger number of eminent contributors to the Yellow Peril discourse took their cue from Japan's victory over the Czarist empire than from the Boxer crisis.

One of these was the German missionary Martin Maier (1866–1954), who by his own account was responding to questions addressed to him upon his return from China. Maier lumped Japan and China together, in part because he attributed the Yellow Peril to racial differences as well as hatred of the "Western" foreigners in both countries.46 He distinguished between a political or military threat, in which he did not believe, and economic competition between East Asians and Europeans. Perhaps owing to his profession, he also warned against the undermining of European ethical achievements through the egotism and materialism of the Chinese and Japanese.47

In contrast to Maier, the German archivist Christian Spielmann (1861–1917) brought some experience to the task. His book Arier und Mongolen (Aryans and Mongols), which first appeared in 1905 and was republished in 1914, drew on two previous works written after the Sino-Japanese War and on the eve of the Boxer War. Spielmann took a stand against a perceived enthusiasm for Japan in the German public, placing the Russo-Japanese War in the larger context of a perennial conflict between Aryans and Mongols. In this conflict the latter were now poised for supremacy, not through spiritual but technological superiority and the sheer force of numbers.48 Like other like-minded writers, Spielmann conjured up the idea of a future Chinese military machine under Japanese guidance that might stage a remake of the medieval Mongol invasion – although this was rather a playing on deep-rooted cultural fears than a sober analysis.49 He also argued that peaceful Chinese emigration presented an equally serious threat, a "swamping of the world which must cause great alarm to the white race".50

Like Spielmann, the Englishman Bertram Lennox Simpson (1877–1930) (writing under the pseudonym B.L. Putnam Weale), a participant in the siege of the Beijing legations in 1900, was writing against the largely positive attitude towards Japan in his country and elaborated on this stance in various works. Unlike his congenial German colleague, however, he had thoroughly revised his former Japan-friendly attitude by the time he published his monumental The Coming Struggle in Eastern Asia. Without actually using the term "Yellow Peril", Simpson polemicised against the Anglo-Japanese alliance of 1902, which he deemed unable to safeguard British interests in view of increasing commercial competition, e.g. in China.51

Superficial as these authors' accounts may have been, they purported to provide a sober and rational analysis of the economic, military and cultural implications of the perceived rise of East Asia. However, the Yellow Peril was also invoked to play on fears of invasion which were a common obsession across Europe in the 1900s. This is achieved in L'invasion jaune, published by the then popular French writer Capitaine Danrit, pseudonym of Colonel Emile-Cyprien Driant (1855–1916), in 1909. The last of an entire series on imaginary wars by the same author, L'invasion jaune describes a joint Japanese-Chinese invasion of Europe, which culminates in the occupation of the Chamber of Deputies in Paris before it can finally be stopped.52

It is doubtful whether Danrit's horror fantasies or the more 'serious' analyses represented the majority or even a significant portion of public opinion. To say the least, a substantial number of authors were convinced that "the 'Yellow Peril' was only a speculation".53 More importantly, the champions of the Yellow Peril discourse failed to grasp the real political-military tensions between East Asia and Europe. The ideology of Pan-Asianism, which gained currency in Japan (and to an extent in China) in the early 20th century, did indeed propagate a defensive front of Asian peoples against white imperialism.54 Although (or rather because) Japan remained a faithful ally of Britain in the First World War, it demanded concessions after the war. Tokyo's abortive push for racial equality at the Paris Peace Conference did not aim to impose a universal principle, but to end anti-Japanese discrimination, reflecting Japan's insecurities as a non-white power. To an extent at least, it was also a reaction to Yellow Peril rhetoric.55 In the 1930s and during the Second World War, Japan increasingly cast itself as the champion of Asian liberation from "white" colonialism. In clinging to Eurocentric fantasies, Yellow Peril literature missed out on what was really (and realistically) at stake.

Legacies

Buzzwords have a long life; they do not die. Instead, they lend themselves to all sorts of adaptations. The Yellow Peril is no exception: its use has changed, but has continued without any real interruption up to the present day.56

Heinz Gollwitzer (1917–1999) was probably right in stating that the broad effect of the Yellow Peril discourse never again reached the dimensions it had assumed between 1895 and 1907 (although he was probably wrong in assuming that it had been almost completely eclipsed by the First World War).57 During this period the discourse was most openly tied to specific media events. This connection was lost in the interwar period although China's anti-imperialist movement of the 1920s would have lent itself for making a connection. Perhaps the Japanese expansion in the late 1930s came closest to arousing a response similar to that of the Russo-Japanese War, but even so the context had changed. The Yellow Peril now had a past as well as a present. Commenting in January 1938 on a speech by the Japanese Minister of the Interior, Admiral Nobumasa Suetsugu (1880–1944), Le Temps warned against his "veritable war cry against the white peoples" and continued:

If such concepts should indeed prevail in certain governing circles in Tokyo, one cannot have any illusions about the evolution of Japanese politics, which are completely directed by the most active military and naval elements. The Yellow Peril, of which the German ex-emperor once spoke, would then become a reality, and the entire white world would have the duty to face it in full awareness of the solidarity of the peoples attached to civilisation, which has created present-day human society.58

On the one hand, anti-Japanese sentiment ran high in the United States during the Pacific War, but it was not directed against the "yellow race" in general. In fact, this would have made little sense, as China had become a sufficiently important ally of the US and Americans had been sympathetic (if patronising) observers of its war against Japan.59

Over time the term Yellow Peril underwent a degree of trivialisation, as it could be adapted to other areas of European-East Asian competition, for example in sports.60 As early as the interwar period, race horses were named after what had once been perceived as an all-out menace to European civilisation.61 Nevertheless the entry of the discourse into popular culture was not always so harmless. A good example is the figure of the Chinese master criminal Fu Manchu, the hero-villain of a book series created by the British author Sax Rohmer, pseudonym of Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward (1883–1959), between 1912 and the late 1950s . The novels were quickly adapted into films, thirteen of which were released between 1921 and 1968.62 In all versions, Fu is depicted as a superhuman criminal combining a brilliant intellect with extraordinary physical prowess. Commanding the "yellow" underworld, he carries the Asian threat into the heart of the "Western" metropolises, London in particular.63 The Fu Manchu stories can be read as a depoliticised but still politically relevant spin-off of a political discourse.

. The novels were quickly adapted into films, thirteen of which were released between 1921 and 1968.62 In all versions, Fu is depicted as a superhuman criminal combining a brilliant intellect with extraordinary physical prowess. Commanding the "yellow" underworld, he carries the Asian threat into the heart of the "Western" metropolises, London in particular.63 The Fu Manchu stories can be read as a depoliticised but still politically relevant spin-off of a political discourse.

However, the idea of the Yellow Peril retained its importance in political and economic debates. After the successful Communist takeover in 1949, the notion was blended with the red scare of the emerging Cold War.64 In subsequent decades, it has underpinned apprehensions about the economic rise of Japan and – yet more recently – of China. Yet since the interwar period, Yellow Peril rhetoric has been more of a steady discourse and not associated with strictly circumscribed media events.

Thoralf Klein

Appendix

Sources

[Anonymous]: Chronique de la semaine, in: Annales catholiques 115 (1900), p. 702.

[Anonymous]: La Chine en flammes, in: La Dépêche, 18 July 1900, p. 1.

[Anonymous]: The Powers and Neutrality, in: The Times, 18 February 1904, p. 3.

[Anonymous]: Racing, in: The Times, 3 September 1924, p. 5.

[Anonymous]: Kempton Park Results, in: The Times, 8 May 1933, p. 4.

[Anonymous]: Jaunes et blancs, in: Le Temps, 4 January 1938, p. 1.

[Anonymous]: Racing, in: The Times, 13 March 1946, p. 2.

[Anonymous]: Triumph für Nippon: Fünf von sieben Tischtennis-Welttiteln gewonnen, in: Passauer Neue Presse, 18 March 1957, p. 5.

Corbach, Christian Paul: Von Kiel bis Peking: Der Boxeraufstand vor 25 Jahren, n.p. 1926.

Danrit, Capitaine (d.i. Emile-Cyprien Driant): L'invasion jaune, Paris n.d. (first published in 1909), URL: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5598999d (only with accreditation).

Davis, Arthur N.: The Kaiser I Knew: My Fourteen Years with the Kaiser, London 1918.

D'Estournelles de Constant: Le péril jaune, in: Le Temps, 28 May 1901, p. 1.

Donnet, Gaston: En Chine, in: Le Temps, 14 November 1900, p. 2.

Donnet, Gaston: Histoire de la guerre Russo-Japonaise, Paris 1904–1905.

Dyer, Henry: Dai Nippon: The Britain of the East: A Study in National Evolution, London 1904.

Grant, N. F. (ed.): The Kaiser's Letters to the Czar, London 1920.

Hart, Sir Robert: These from the Land of Sinim: Essays on the Chinese Question, London 1901.

Moulin, René : Le péril jaune, in: Revue hebdomadaire 13,37 (1904), pp. 129–147.

Navalis: The peril in the Far East, in: The Times, 12 June 1900, p. 7.

Putnam Weale, B.L. (d.i. Bertram Lennox Simpson): The Coming Struggle in Eastern Asia, London 1908.

Spielmann, Christian: Arier und Mongolen: Weckruf an die europäischen Kontinentalen unter historischer und politischer Beleuchtung der Gelben Gefahr, 2nd. ed., Halle an der Saale 1914.

van Blättjen, Pieter: Die gelbe Gefahr hat rote Hände: Ein Chinabericht aus dem Winter 1962/63, Graz 1963.

Wilson, Herbert Wrigley: Japan's Fight for Freedom: The Story of the War Between Russia and Japan, vol. 1–3, London 1904–1906.

Literature

Aydin, Cemil: The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia: Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought, New York 2007.

Baker, Phil / Clayton, Antony (ed.): Lord of the Strange Deaths: The Fiendish World of Sax Rohmer, London 2013.

Barth, Boris / Osterhammel, Jürgen (ed.): Zivilisierungsmissionen: Imperiale Weltverbesserung seit dem 18. Jahrhundert, Konstanz 2005.

Bösch, Frank: Europäische Medienereignisse, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2010-12-03. URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/boeschf-2010-de [2015-06-05].

Brown, Penny: A Critical History of French Children's Literature: vol. 2: 1830–present, London 2008.

Clegg, Jenny: Fu Manchu and the 'Yellow Peril': The Making of a Racist Myth, Stoke-on-Trent 1994.

Cohen, Paul A.: History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience and Myth, New York 1997.

Conrad, Sebastian: Globalization and the Nation in Imperial Germany, Cambridge 2010.

Connaughton, Richard: The War of the Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear, London 1991.

Dayan, Daniel / Katz, Elihu Katz: Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History, Cambridge, MA 1992.

Elliott, Jane E.: Some Did It for Civilisation, Some Did It for Their Country: A Revised View of the Boxer War, Hong Kong 2002.

Eskildsen, Robert: Of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan, in: American Historical Review 107 (2002), pp. 388–418.

Esherick, Joseph W.: The Origins of the Boxer Uprising, Berkeley, CA 1987.

Fahlenbrach, Kathrin: Körper-Revolten und mediale Körperinszenierungen: Die Proteste um '68 als Medienereignis, in: Frank Bösch / Patrick Schmidt (ed.): Medialisierte Ereignisse. Performanz, Inszenierung und Medien seit dem 18. Jahrhundert, Frankfurt am Main 2010, pp. 223–245.

Foucault, Michel: The Archaeology of Knowledge, New York 1972.

French, Paul: Through the Looking Glass: China's Foreign Journalists from the Opium Wars to Mao, Hong Kong 2009.

Gassert, Philipp: "Völker Europas, wahrt Eure heiligsten Güter': Die Alte Welt und die japanische Herausforderung, in: Maik-Hendrik Sprotte / Wolfgang Seifert / Heinz Löwe (ed.): Der Russisch-Japanische Krieg 1904/05: Anbruch einer neuen Zeit?, Wiesbaden 2007, pp. 277–293.

Gollwitzer, Heinz: Die Gelbe Gefahr: Geschichte eines Schlagworts: Studien zum imperialistischen Denken, Göttingen 1962.

Hevia, James L.: Leaving a Brand on China: Missionary Discourse in the Wake of the Boxer Movement, in: Modern China 18 (1992), pp. 304–332.

Hevia, James L.: English Lessons: The Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth-Century China, Durham, NC 2003.

Iikura, Akira: The "Yellow Peril" and its influence on Japanese-German relations, in: Christian W. Spang / Rolf-Harald Wippich: Japanese-German Relations, 1895–1945: War, diplomacy and public opinion, London 2006, pp. 80–97.

Jespersen, T. Christopher: American Images of China, 1931–1949, Stanford, CA 1996.

Kaminski, Gerd: Der Boxeraufstand – entlarvter Mythos: Mit Beiträgen österreichischer Augenzeugen, Vienna 2000.

Klein, Thoralf: Propaganda und Kritik: Die Rolle der Medien, in: Mechthild Leutner / Klaus Mühlhahn (ed.), Kolonialkrieg in China: Die Niederschlagung der Boxerbewegung 1900–1901, Berlin 2007, pp. 173–180.

Klein, Thoralf: Criticizing the Eight-Power Intervention: Left-wing Newspapers in Germany and France, 1900–1901, in: Zhongguo Yihetuan Yanjiuhui (ed.), Yihetuan yundong 110 zhounian guoji xueshu taolunhui wenji [Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium Commemorating the 110th Anniversary of the Boxer Movement], Jinan 2013, pp. 820–834.

Klein, Thoralf: Die Hunnenrede (1900), in: Jürgen Zimmerer (ed.), Kein Platz an der Sonne: Erinnerungsorte des deutschen Kolonialismus, Frankfurt am Main 2013, pp. 164–176.

Koselleck, Reinhart: Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time, New York 2004.

Maier, Martin: Die "Gelbe Gefahr" und ihre Bekämpfung vom christlichen Standpunkte aus, in: Evangelisches Missions-Magazin: Neue Folge 49 (1905), pp. 105–129, 157–183.

Mayer, Ruth: Serial Fu Manchu: The Chinese Supervillain and the Spread of Yellow Peril Ideology, Philadelphia, PA 2013.

Mehnert, Ute: Deutschland, Amerika und die "Gelbe Gefahr": Zur Karriere eines Schlagworts in der Großen Politik, 1905–1917, Stuttgart 1995.

Mollenhauer, Daniel: Parliamentary Debates as/and Media: The Boxer War in the German Reichstag and the French Chambre des deputes, Paper presented at the conference "The Boxer War and its Media", Erfurt 17. –19.07.2009.

Porra, Véronique: Die fiktionale Verarbeitung der 'Gelben Gefahr' als Artikulation frankozentrischer Diskurse: Das Beispiel von Danrits L'invasion jaune (1905–1909), in: Walter Gebhard (ed.), Ostasienrezeption zwischen Klischee und Innovation: Zur Begegnung zwischen Ost und West um 1900, München 2000, pp. 185–207.

Reinkowski, Maurus / Thum, Gregor: Helpless Imperialists: Introduction, in: Maurus Reinkowski / Gregor Thum (ed.), Helpless Imperialists: Imperial Failure, Fear and Radicalization, Göttingen 2013, pp. 7–21.

Sharf, Frederick A. / Ulak, James T.: A Well-Watched War: Images from the Russo-Japanese Front 1904–1905, Newbury, MA 2000.

Shimazu, Naoko: Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919, London 1998.

Slattery, Peter: Reporting the Russo-Japanese War 1904–5: Lionel James' First Wireless Transmissions to The Times, Folkestone 2004.

Steinberg, John W. et al. (ed.): The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero, Leiden 2005.

Su Weizhi / Liu Tianlu (ed.): Yihetuan yanjiu yibai nian [A Century of Research on the Boxers], Jinan 2000.

Tchen, John Kuo Wei / Yeats, Dylan: Yellow Peril!: An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear, London 2014.

Tipton, Elise K.: Modern Japan: A Social and Political History, 2nd. ed., Abingdon 2008.

Trampedach, Tim: "Yellow Peril"?: German Public Opinion and the Chinese Boxer Movement, in: Berliner China-Hefte: Chinese Culture and Society 23 (2002), pp. 71–81.

Winseck, Dwayne R. / Pike, Robert M.: Communication and Empire: Media, Markets, and Globalization 1860–1930, Durham, NC 2007.

Wolff, David et al. (ed.): The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero. vol. 2, Leiden 2006.

Xiang, Lanxin: The Origins of the Boxer War: A Multinational Study, London 2003.

Notes

- ^ See Barth / Osterhammel, Zivilisierungsmissionen 2005.

- ^ See Reinkowski / Thum, Helpless Imperialists 2013, in particular pp. 11–13.

- ^ See the classical studies by Gollwitzer, Die Gelbe Gefahr 1962 and Mehnert, Deutschland, Amerika und die "Gelbe Gefahr" 1995, in particular pp. 28–33; cf. also Trampedach, "Yellow Peril" 2002.

- ^ I use "discourse" here in the specific sense developed by Michel Foucault, who defines discourses as "practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak". A "discourse" is therefore not simply a discussion of a particular object, but the discussion itself brings that object into being. See Foucault, Archaeology 1972, p. 49.

- ^ This section follows the outline in Mehnert, Deutschland 1995, p. 35–58, although I have partly rearranged the order of her main points.

- ^ Conrad, Globalization 2010, p. 224; Mehnert, Deutschland 1995, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Gollwitzer, Die Gelbe Gefahr 1962, pp. 68–93, focuses mainly on intellectual debates and less on the more effective popular agitation.

- ^ Conrad, Globalization 2010, pp. 203–208; for the following remarks see Conrad, Globalization 2010, pp. 221f.; Mehnert, Deutschland 1995, p. 41.

- ^ Cf. Mehnert, Deutschland 1995, pp. 35–37, 43–49; Trampedach, "Yellow Peril" 2002.

- ^ The quotation is from Dayan / Katz, Media Events 1992, p. 1.

- ^ For media events as condensations of social discourses cf. Bösch, Europäische Medienereignisse 2012.

- ^ Winseck / Pike, Communication and Empire 2007, for the incorporation of China see pp. 113–141.

- ^ Slattery, Reporting 2004, p. xii.

- ^ Koselleck, Futures Past 2004, p. 106. At this point it should be noted that media do not always merely react to external circumstances; on the contrary, they may create events in the first place (see Fahlenbrach, Körper-Revolten 2010, p. 230).

- ^ See the extensive bibliography of titles in English, German, French and Italian compiled by R. G. Tiedemann in Su / Liu, Yihetuan 2000, pp. 623–775. Finally, it should be noted that in a sense, both "real" and media events are constructs in that they are carved out of a continuum of human action and communication.

- ^ Gollwitzer, Die Gelbe Gefahr 1962, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Eskildsen, Of Civilization 2002.

- ^ Tipton, Modern Japan 2008, pp. 76f.

- ^ Iikura, The "Yellow Peril" 2006, pp. 81ff.

- ^ The discussion in the literature seems to rely on the testimony of Wilhelm's American dentist: Davis, The Kaiser 1918, p. 110. For a wider context see Gollwitzer, Die Gelbe Gefahr 1962, p. 42f.

- ^ See Wilhelm's letter to Czar Nicholas II., Jagdhaus Rominten 26 September 1895, in: Grant, The Kaiser's Letters 1920, p. 19.

- ^ Gassert, "Völker Europas" 2007, pp. 284ff.

- ^ Wilhelm's authorship is emphasised Gassert, "Völker Europas" 2007, p. 17f. and in Wilhelm's letter to the Czar, Berlin 6 June 1904, in: Gassert, "Völker Europas" 2007, p. 118. For the context see Iikura, The "Yellow Peril" 2006, pp. 81–88.

- ^ Although this designation is not yet universally accepted, it is increasingly replacing the traditional term "Boxer Uprising", which reflects a colonial perspective.

- ^ For lack of space a detailed discussion of the research on the Boxer movement and the international intervention it triggered cannot be provided. The most relevant studies are Xiang, The Origins of the Boxer War 2003, Hevia, English Lessons, 2003, Cohen, History in Three Keys 1997 and Esherick, The Origins 1987.

- ^ Hevia, Leaving a Brand 1992, p. 307.

- ^ There is as yet no comprehensive analysis of news reporting on the Boxer War. For preliminary studies see Klein, Propaganda und Kritik 2007; French, Through the Looking Glass 2009.

- ^ French, Through the Looking Glass 2009, pp. 66–75; cf. also Elliott, Some Did It 2002, pp. 1–50.

- ^ Klein, Propaganda und Kritik 2007, pp. 176ff.; Hevia, English Lessons 2003, pp. 231–240.

- ^ Mollenhauer, Parliaments as/and Media 2009; Klein, Criticizing 2013, especially pp. 831–833.

- ^ [Anonymous], Chronique 1900, p. 702. Interestingly, the article included the subheading "The Yellow Peril" (Le péril jaune) without picking up the concomitant rhetoric.

- ^ [Anonymous], La Chine 1900, p. 1. Che Kiang [= Zhejiang] is actually a province, Wenzhou and Taizhou are cities within that province, Che-Fou [= Zhifu or Yantai] is a port city in Shandong province.

- ^ Navalis (pseudonym), The peril 1900, p. 7.

- ^ Donnet, En Chine 1900, p. 2.

- ^ For a recent analysis of the speech see Klein, Die Hunnenrede 2013, pp. 167–171. In contrast cf. Trampedach, "Yellow Peril" 2002, who in my view wrongly conflates the Yellow Peril discourse with that on civilization and barbarism.

- ^ See Corbach, Von Kiel bis Peking 1926, p. 6.

- ^ D'Estournelles de Constant, Le péril jaune 1901, p. 1.

- ^ Hart, These from the Land 1901, pp. 50, 54.

- ^ Hart, These from the Land 1901, p. 52.

- ^ Hart, These from the Land 1901., pp. 59, 111–13.

- ^ For a detailed overview of the conduct of the war, see Connaughton 1991; all relevant aspects of the war are covered by two magisterial volumes: Steinberg, The Russo-Japanese War 2005 and Wolff et al., The Russo-Japanese War 2006.

- ^ [Anonymous], The Powers 1904, p. 3.

- ^ Wilson, Japan's Fight 1904–06; cf. Sharf / Ulak, A Well-Watched War 2000, p. 6f.

- ^ Donnet, Histoire 1904–05. The complete series consisted of 65 issues.

- ^ Moulin, Le péril jaune 1904, p. 129 ; cf. Gassert, "Völker Europas" 2007, p. 288.

- ^ Maier, Die gelbe Gefahr 1905, pp. 106ff.

- ^ Maier, Die gelbe Gefahr 1905, pp. 113, 122–123.

- ^ Spielmann, Arier und Mongolen 1914, pp. iii–v. Gollwitzer 1962, pp. 177f., only analyses Spielmann's first book, Der neue Mongolensturm, published in 1895. According to Gollwitzer, Spielmann actually was a pacifist. On the basis of Arier und Mongolen, Kaminski (Boxeraufstand 2000, p. 213) dismisses Spielmann as a racist.

- ^ Kaminski, Boxeraufstand 2000, pp. 315–319.

- ^ Kaminski, Boxeraufstand 2000, pp. 318.

- ^ Putnam Weale, The Coming Struggle 1908, pp. 625–640.

- ^ Danrit, L'invasion jaune n.d., especially pp. 816ff.; for the background see Brown, A Critical History 2008, pp. 145f., for a detailed analysis cf. Porra 2000.

- ^ Dyer, Dai Nippon 1904, p. 393.

- ^ Aydin, The Politics 2007.

- ^ Shimazu, Japan, Race, and Equality 1998, pp. 164–188.

- ^ This is demonstrated in an impressive manner in Tchen and Yeats, Yellow Peril 2014.

- ^ Gollwitzer, Die Gelbe Gefahr 1962, pp. 219ff.

- ^ [Anonymous], Jaunes et blancs 1938, p. 1. The past of the phrase is also evoked in obituaries on Kaiser Wilhelm II. in 1941.

- ^ Jespersen, American Images 1996, especially pp. 46ff.

- ^ See, for example [Anonymous], Triumph 1957, p. 5.

- ^ Horses named "Yellow Peril" are mentioned in [Anonymous], Racing 1924, p. 5; [Anonymous], Kempton Park 1933, p. 4; [Anonymous], Racing 1946, p. 2. Clearly these were three different animals.

- ^ For the films see Clegg, Fu Manchu 1994, p. 3.

- ^ The interest in Fu Manchu, especially of literary critics, has grown since the 100th anniversary of the series; cf. Mayer, Serial Fu Manchu 2013, and Baker / Clayton, Lord of the Strange Deaths 2013.

- ^ Echoes of this can be found in van Blättjen, Die gelbe Gefahr 1963, p. 163.

![Hunnenrede IMG Verabschiedung des deutschen Expeditionskorps durch Kaiser Wilhelm II. [Hunnenrede] vor der Einschiffung nach China in Bremerhaven, black-and-white photograph, 1900, unknown photographer; source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1970-068-53 / CC-BY-SA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1970-068-53,_Bremerhaven,_Verabschiedung_des_ostasiatischen_Expeditionskorps.jpg, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en.](./illustrationen/yellow-peril-bilderordner/hunnenrede-img/@@images/image/thumb)