Icons in the Orthodox Tradition

Origins

The word "icon" (Gr. εἰκών/εἰκόνα) primarily means "image", "likeness", "representation", or "depiction".1 However, the concept of "(holy) icon" is used in the Christian tradition to characterize not just any image or representation but, more specifically, the depiction of "Christ, Mother of God, a saint or an event from the sacred history, whether it be a sculpture or a painting on wood or on wall, regardless of the technique applied".2 In its contemporary usage in the Orthodox Church, the word is usually applied to the above-mentioned depictions that are painted on wooden panels, placed individually or as parts of iconostasis (altar screen).

Many Orthodox theologians call icons "theology in colors"3 to stress that it is not simply a form of art which is used in or by the Church; the significance of icons lies in their capacity to express the Christian faith and to "iconize" (make present, although not fully and perfectly) the Kingdom of God already in the course of history. For these reasons, icons are honored the same way Christians have traditionally venerated the cross, or the Holy Scripture; the Scripture expresses Christian faith with words, while icons do so with visual elements.

Orthodox theology thus uses the concept of "icon" not only for visual representations of saints, but also for any media, actions, objects and even persons that perform this "iconic" role of "making present" here and now "things invisible" (cf. Romans 1,20). In this sense, if one understands Christian faith as "the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen" (Hebrews 11,1), an icon can be understood as a materialized faith, faith given "shape and body" in the course of history.4

Using visual representations in Christianity has a very long tradition. In the early Christian places of worship (domus ecclesiae) and in burial sites (catacombs), the most important rituals, personalities and narratives from the Church tradition were depicted, often employing vivid symbols.

After the legalization of Christianity under Constantine the Great (ca. 280–337) the state became the major patron of the Church. This, together with making Christianity the only legal faith of the Roman Empire (under Theodosius I, 347–395), allowed for an enormous expansion of Christian art. Christian images started to be produced on a massive scale, in order to decorate the large walls of the newly constructed basilicas. In the early period there was no consistent Christian image theory. For a developed theology of icons, one had to wait until the period of iconoclasm.

Theology of icons

The iconoclastic crisis in the Eastern Roman Empire was initiated by the first iconoclastic emperor, Leo III. (ca. 675–741), with a series of edicts that prohibited the use of images. It resulted in a major conflict, which continued to trouble the Empire for more than a century. The theology of icons that was formulated during this period would become canonical for the later Orthodox Christian tradition.

The iconoclasts accused the iconophiles of idolatry, impiety and heretical innovations that were against the tradition. From the iconoclastic perspective, making images of Christ violated the Old Testament prohibition not to make any image "in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below" (Exodus 20,4). This argument was easy to repudiate. One of the major iconophile theologians, John of Damascus (675–749), used the same source to show that if this commandment had been absolute in its character then God would have contradicted himself,5 as God ordered Moses, in Exodus 25, to make "two cherubim" for the Arc of the Covenant.6 This indicated that the prohibition was not absolute but relative to the context and suited for a particular place and time, in order to prevent idolatry. If God remained invisible, argues further John of Damascus, it would be impossible and, indeed, idolatrous to depict him.7 However, since God (the Son), following the Christian dogma of the Incarnation, became a human being (meaning that he appeared in a visible form) without ceasing to be God, Christ not only can but should be depicted. Those depictions of the Incarnate God (i.e. icons) function as a profession of faith that God truly, not seemingly, became a human being.8 This means that the possibility of making visual depictions becomes intrinsically linked with the belief in the Incarnation of God the Logos, and vice-versa: negating the possibility of visual depictions means an implicit negation of the dogma of the Incarnation.9

In addition to this, the iconophiles were able to point to the long tradition of visual depictions in the Church, stretching back, as we have seen, to the first centuries AD, as well as to some of the authoritative Church Fathers, who explicitly or implicitly defended icons, such as Athanasius of Alexandria (295–373), St. Basil the Great (33—379), Gregory of Nyssa (ca. 335–394), Cyril of Alexandria (380–444) and others.10

The major role in formulating theologically much more sophisticated arguments against icons played the son of Leo III, emperor Constantine V. (ca. 718–775). He claimed that painting icons (and venerating them) inevitably led to one of the heresies that the Church Councils had already condemned in the previous centuries. Following this line of argumentation, since the divine nature cannot be depicted, what the iconophiles do when they paint icons is that they either separate the divine and human natures in Christ (which is the heresy of Nestorianism), or they confuse them, ending up in some form of Monophysitism.11

The iconophile theologians responded in the following way: when one portrays someone, it is not nature that is depicted, but rather the person (hypostasis). Consequently, when making an icon of Christ, it is not his nature (divine or human) that is depicted, but the person of Jesus Christ (who has both divine and human natures that exist in that person without separation and without confusion).12

It seems that the iconoclasts also claimed that icons, in order to be true, must be of the same substance with the prototype, so the only "true icon" would be the Eucharist.13 In response to this, the iconophiles pointed out that (material) icons are precisely that, icons (images), because they are not of the same substance with the prototype. The prototype is a person, and an icon is a depiction of that person in a certain material (medium), which has some resemblance with the prototype but is clearly different from it (being an image).

For the iconophiles, the affirmation of icons also meant the affirmation of the material world. Certain "spiritualistic" tendencies that can be seen in the iconoclastic argumentation, made the iconophiles to assume a strong position on the importance of matter and the material world, which was affirmed through the Incarnation of Christ, and therefore is also affirmed in the practice of icon painting.14

This theology of icons was accepted as the Orthodox position at the Seventh Ecumenical Council (787). The council accepted the classical formulation of St. Basil the Great that the "honor offered to the image passes to the archetype (original)",15 and ordered that respect (honor) should be paid to the icons by proskynesis (bowing down) in front of them, because the respect shown in front of an icon does not mean veneration of a material object but rather respect for the prototype (Christ). The council was careful to also warn that icons should not be worshiped or adored (latreia), which would be idolatry, as the true worship belongs only to God.16 Worshipers of icons were threatened with excommunication.

What is important to notice here is that throughout the discussion about icons and their theology, the visual or aesthetic side of icons (apart from the affirmation of the materiality of this world, and thus, of icons as well) did not play any role. Icons were discussed in terms of their importance for the Christian doctrine, their role in the liturgy and the church, their implications as to some of the core elements of Christian faith. How to paint icons, what visual language or style to use in order to depict Christ or saints, was probably regarded as a technical issue, which was not very relevant for the central (theological/doctrinal) topics of the iconoclastic dispute.

Aesthetic properties

As Leonid Uspenski (1902–1987) pointed out, icons are not limited to any particular medium. Icons can appear as visual depictions on wood or walls, executed in tempera, mosaic, fresco or other techniques, and they can even include three-dimensional forms.17 For many lay people, priests and theologians, the "canonical" visual appearance of icons is intimately linked with the forms in which they appeared in the tradition of the Eastern Roman Empire, and in the artistic traditions of the "Byzantine Commonwealth" (the territories that were under the dominant cultural, political, economic and/or ecclesiastical influence of Constantinople). One reason for that can be found in the fact that some of the masterpieces of icon painting that would receive a wide-spread recognition for their beauty, were produced in the Eastern Empire, or in the "commonwealth" territories. Examples would include the fourth and fifth century mosaics of Ravenna, portable and fresco icons of late Byzantine

and Medieval Serbian art

or, 15th century Russian painting.

However, the problem with the idea that there is (or that there was) a "canon" of icon painting is that it ignores the simple fact that there has never been one style or one prescribed way of how to depict religious scenes. In actual reality there were a variety of visual approaches to icon painting, depending on the geographical region where icons were produced, the time of their production and the skill of the painter(s) (who mostly worked in workshops).

In addition to that, the development of the visual language and artistic styles of icons did not stop in the Medieval or in the Early Modern period, although the Turkish invasion of many regions previously occupied by the Eastern Empire caused a major obstacle in the further development of Christianity-inspired culture (including icon painting). A notable exception in this regard was Russia, where icon painting continued to flourish. During the course of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, both in Russia and in other regions inhabited by the Orthodox population outside the Ottoman Empire (e.g. in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy), church art fell under a strong influence of the dominant artistic styles of Western Europe, such as Baroque, Rococo or Romanticism.

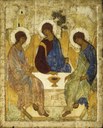

The adaptation of the Western artistic styles in the modern period was perceived by many in the Orthodox world as some kind of "Babylonian slavery" of Orthodox iconography, waiting to be rescued in order go back to its own, "authentic" visual tradition best exemplified by the Medieval icons mentioned above. Despite the apparent differences between, for instance, the sixth century icons of Ravenna and the visual elements employed by Andrei Rublev (1360–1430), these earlier depictions would continue to be perceived as constituting the "canonical style" in which Orthodox icons should continue to be depicted

Many 20th-century authors gave the medieval styles and their aesthetic properties an elaborate theological explanation and justification. A couple of main elements from the visual language of traditional icon painting were taken to be fundamental for the proper theological functioning of icons. First of all, that includes the stylized forms that have been interpreted as being capable of iconizing "eschatology". Forms in icons which often appear as illogical, defying the laws of physics, have been interpreted as depicting not simply the appearance of human beings and other objects in the world as they appear in historical reality (which would imply some kind of "realism"), but also as symbols of a future existence in the Kingdom of God, which will be free from the constrainst we find in this world.18 Directly connected with this are the specific light and shading effects that we find in icons – and which were linked to Hesychasm – and the possibility of human divinization (theosis).19 Other elements characteristic for traditional icon painting include the inverse perspective and the use of gold (for the backgrounds or aureoles) which can also be interpreted as symbolizing the light of the Kingdom of God (cf. Revelation 21,10-11).20

Icons and the West

Theology of icons and image theory in Western Europe

The reception of the theology of icons in the West was somewhat paradoxical. For the whole duration of the iconoclastic dispute, the papacy supported the iconophile party against the iconoclastic emperors. However, it seems that the issues at stake that were so hotly debated in the East were not quite well understood in the West (or were, perhaps, even intentionally misunderstood). Thus, at the Seventh Ecumenical Council the letter of the bishop of Rome was read, which represented a strong moral support for the iconophiles, but its content was, theologically speaking, irrelevant for the issues discussed. Nevertheless, the papal delegates endorsed the Council and signed its documents that affirmed the veneration of images and ordered bowing down (proskynesis) in front of them.

A Latin translation of the documents (originally written in Greek) was made and sent to Charlemagne (742–814). This unfortunate translation only contributed to the confusion, since it was not clear how the proper way of relating to icons, that the decrees talked about, was not idolatry or superstition. Paradoxically enough, what the Council had explicitly condemned – the adoration of icons – under the threat of excommunication, was understood as something that the Council had, at least partly, advocated for.21

However, as in the case of the Eastern iconoclasm, the issue here was not strictly theological or ecclesial, but – even more – political. It coincided with Charlemagne's aspirations to imperial power (which was difficult to legitimize given the presence of the only legitimate Roman emperor in Constantinople), and the interest of the papacy, which sought a new political alliance once the (Eastern) Roman Empire was weakened and absent from most of its traditional territories on the Italian peninsula.

In response to the Seventh Ecumenical Council, Charlemagne's council of Frankfurt (794) rejected the decisions of the "synod of the Greeks", and the "adoration" of images. The major theological work composed at Charlemagne's court, which later became known as Libri Carolini (prepared by Theodulf (ca. 750–821), later bishop of Orléans), produced an alternative image theory.22 As Umberto Eco (1932–2016) noticed, the value of images was judged here in terms of their aesthetic properties and this aesthetics was one of "pure visibility… and at the same time an aesthetics of the autonomy of the figurative arts".23 The elimination of the theological argumentation and Christological implications of the production of images opened up the space for the idea of an "autonomy" of images, which would only fully be developed in modern aesthetics and the idea of "autonomy" of art.

In the West the theology of icons became relevant again in the 16th century with the Counter-Reformation. To the challenges posed by the Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church responded with the Council of Trent (1545–1563). Among a variety of issues, the Council also dealt in its last session with the issue of images that most of the Protestant theologians considered idolatrous. The Council returned here to the formulations of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, ordering that honor and veneration are to be given to images, since the honor given to images refers to the prototype they depict.24

Stylistic influences

Given the preeminent position of the Eastern Roman Empire in the Christian world for a very long time, Constantinople exercised a dominant cultural and artistic influence over the neighboring territories. Its influence on European art can clearly be traced for over a millennium. Painting in Carolingian as well as Romanesque times developed under a strong influence of Eastern Roman art and, in many cases, as its natural continuation. Paintings were often executed by artists who either came from the Eastern Empire or whose workshops were influenced by the workshops of Constantinople and other artistic centers of the Greek-speaking regions.25 These connections with Eastern Roman painting can best be seen in the Italian regions which had traditional ties with Constantinople, such as Ravenna, Sicily or Venice.

The design of St. Mark's cathedral in Venice (11th century) followed the architecture of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. Layers of its decoration remain organically linked with the traditional painting from the imperial capital. The same features can be seen in the famous 12th-century mosaic from Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome

, (which also introduced an important iconographic innovation). Even after the fall of the Eastern Empire in 1453, some of the famous icon painting workshops continued to operate and to service its western (primarily Venetian) customers. A famous example is Crete (Regno di Candia, 1212–1669

.

Major developments of the 14th and 15th centuries (primarily in the Italian peninsula) led to a new cultural and artistic climate, which would become known as the Renaissance. The visual language of painting changed, although in its early (proto-Renaissance) phase one can still see much of the traditional Eastern Roman icon paintings that developed new aesthetic properties only slowly. The Renaissance artists eventually abandoned many elements that characterized this traditional type of painting, such as the inverse perspective, golden backgrounds and aureoles, or the traditional (stylized) facial features with which saints were depicted. Instead, they would use linear perspective, creating an illusion of deep, three-dimensional space in which the depicted figures (modeled to resemble three-dimensional shapes) are situated, often painted after living models. The result was a different type of painting, which contextualized Christian religious narratives and religious art in a new way

.

It became clear that from the period of the (High) Renaissance, the mainstream tendencies in religious art in the West were taking a different course compared to traditional icon painting. This was indicative of a bigger political, cultural and religious gap widening between the "Greek East" and the "Latin West". The contrast between the "eastern" icons and modern (religious) art in the West received its classical expression in the words of Gregory Melissimos, a Greek participant at the council of Ferrara (1438–39), who claimed that he could not venerate (the images of) the saints depicted in Latin churches as he could not recognize them.26

However, even in some of the most prominent manifestations of Renaissance and post-Renaissance Western European art, a careful observer will be able to see the influences of traditional icon painting. One example is the famous Last Judgment from the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564). In spite of a powerful display of forms and colors that have been considered highly original (and already announce the dynamism and the theatrical effects typical of the Baroque period), including a remarkably different treatment of the human body compared to traditional Christian art, the general compositional scheme follows earlier examples from the icon painting tradition depicting the same subject.27 This can be seen in the existence of the three main horizontal registers into which the composition is divided, with the figure of Christ occupying the upper central position (surrounded by the Virgin and a saint), with two more upper fields (left and right), that are usually reserved for angelic figures in traditional icons.

The most remarkable case of the transposition of stylistic elements of icon painting (as well as some of its compositional and iconographic solutions) into the Western post-Renaissance artistic context is the art of Doménikos Theotokópoulos (ca. 1541–1615), called El Greco. This artist from Crete had been trained in the traditional icon painting before he moved to Rome where he fell under the influence of Mannerism. His final destination was Toledo (Spain), where he developed his unique style (often considered one of the most important manifestation of Baroque painting in Spain). Both in their iconography and, more so, in their style, his mature paintings exhibit many traces of the logic of traditional icon-painting, including the elongated human figures, the stylized faces and the light effects that do not display chiaroscuro effects produced by a natural source of light.

Icons and (post)modernity

Icons and modernity

The complex political and cultural developments – outlined in general terms above – led to the perception that the Medieval "Byzantine" style of icon painting was to be equated with the "Orthodox style". This produced a twofold effect. On the one hand, the Orthodox style was dismissed as buried in the past, a reflection of an essentially static tradition of Orthodoxy, incapable of embracing new cultural and stylistic developments. On the other hand, the "pre-modernity" (or "non-modernity") of icons also became a source of inspiration and fascination as icon painting was perceived as a truer and more profound type of art, which was especially appealing to the Romanticist imagination. However, as we have seen, the situation was much more complex. Stylistic influences of the art of the Eastern Empire were embraced in the West not only before the fall of Constantinople (1453)

Icon painting in the traditionally Orthodox context was also not immune to new developments in the West. Despite its perception as an inherently conservative type of painting, the tradition of icon painting has been shaped by constant "reinventions", depending on a number of circumstances, such as cultural specificities, economic situation, availability of skilled painters, etc. For instance, in the 14th century one can already discern important stylistic changes in traditional iconography. The painting of the so-called "decorative style" adorning the churches of late medieval Serbia, have been interpreted as exhibiting elements of "renaissance humanism" within the late Byzantine-style.

The absorption of the Baroque (later also Rococo) style in the Orthodox Church is also a well-known phenomenon. In 18th-century Russia, as well as in the territories under Austrian and Hungarian rule, many Orthodox Churches, their walls and iconostases, were decorated in styles (and sometimes also iconographical features) modeled on Western prototypes. In addition to these, 19th- and early 20th-century church art absorbed elements and methods of romanticism, realism and symbolism, both in Russia and in other traditional Orthodox contexts.

Many of these developments are routinely dismissed by more conservative Orthodox theological and church circles under the pretext that they represent a "Babylonian slavery" of Orthodox iconography under the Western artistic influences. However, one cannot deny that many of those paintings became liturgical art, and, as such, an organic part of the Orthodox tradition. A productive exchange between modern ("Western") art and (traditional) icon painting continued into the 20th century as traditional icons became a major source of inspiration for some of the most prominent avant-garde art movements.

Icons and modern art

The topic of icons and modern art became the subject of more systematic academic explorations only recently.28 The connection, however, between Russian avant-garde art and traditional icon painting was apparent both to the artists and many contemporary observers. The formal properties of traditional (Russian) icons, such as their quality of flatness, bright colors, inverse perspective, often simple and clear (abstract) geometrical forms, spoke to the imagination of modern artists. There was also a fascination with the "primitivism" (i.e. the pre-modern and especially "non-Western" character) of icons, comparable to the fascination of cubists and other modern artists in the West with non-European "primitive" art. This was especially true of the neo-primitivism movement, and its best-known representatives Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) and Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964). Especially Goncharova's work was heavily influenced both by the formal properties of traditional icons and by their iconography.

The specific representation of light in traditional icon painting and the stylized abstract forms inspired many artists, some of which were later known as "Russian Constructivists," including Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956) and Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953). In his earlier work Tatlin painted saints based on traditional iconographic styles but later also used the visual language of icons when painting non-religious motifs. Formal elements, such as the inverse perspective and the rays of light so clearly visible in some icons can be related to both cubo-futurism and rayonism.

Probably the most complex engagement with icon painting we find in the work of Kasimir Malevich (1878–1935). In Malevich's Suprematism both the (abstract) formal elements and the "spiritual" meaning of icons are reflected and transformed into a new kind of image. His "Black Cross" and "Black Square" were not just new "icons" of the purely metaphysical (but also purely artistic/painterly) suprematist reality, but this "suprematist icon" even took the place within the interior traditionally reserved for icons

.29

In addition to these artists, both Marc Chagall (1887–1985) and Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1947) – although very different in their artistic poetics – drew more inspiration from the iconographic and spiritual resources of traditional icons than from their formal qualities. Icons also fascinated non-Russian artists. Henri Matisse (1869–1954), for example, was deeply impressed by the art of icon painting during a visit to Russia (although it is not clear whether or not this made a concrete impact on his later art).30 Icons remained an important point of reference and a source of inspiration beyond the concerns of modern art and the medium of painting. They served as a point of reference in thinking about, for instance, abstract expressionism, "aesthetics of absence", various manifestations of conceptual art, etc.31

In another addition to the complex relationships between icons and modern art contemporary icon painting makes use of many visual elements of modern art. Many icon painters, both in traditional Orthodox contexts and in Western Europe and North America, draw their inspiration from impressionism, expressionism, cubism, art informal, or abstract expressionism. Some of their works have already been used in liturgical environments, thus acquiring a liturgical approval as "real" icons, i.e. images of the eschatological reality, which is "already" and "not yet".

Icons and contemporary culture

Icons remain an important point of reference and a source of inspiration beyond the concerns of modern art and the medium of painting. In recent decades icons also became relevant for new types of media such as film. For example, icons play a central role in films such as Andrei Rublev (1969) by Andrei Tarkovsky or in Vreme čuda (1989) by Goran Paskaljević. The concept of "simulactum" and the proliferation of digital images at the end of the 20th and in the beginning of the 21st century, gave rise to contemporary image theories that revisit the relationship between the image and "reality". In this context, the functioning of traditional icons within the liturgical context, as well as the theology of icons, provide a fruitful resource for thinking about "reality of images" without ending up in some kind of image fetishism. Viewed from this perspective, the "reality of images (icons)" can appear as ontologically superior ("more" or "hyper real") to "mere reality".32