Introduction

Soldiers differ from civilians in dress, their possession of the legal right to kill and injure, adherence to particular codes of honour and behaviour, and submission to military law.1 The employment of mercenaries, which occurred extensively before 1648 and again during the later decades of the 20th century, has tended to blur these boundaries. Mercenaries frequently wear no official uniform and have often operated outside both military law and the command structures of national armed forces. Legally they are civilians. The most recent manifestation has been the employment of tens of thousands of substantially-armed mercenaries wearing civilian clothes – euphemistically referred to as "security guards", "contractors" and "reconstruction workers" – in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, as well as the Trans-Caucasus, Iraq and Afghanistan. Most have been specifically exempted from civil and military jurisdiction by various governments and have been allowed to kill with a degree of impunity. The operational conduct of the hirelings of the big mercenary firms – Blackwater (now Xe Services LLC), Aegis, DynCorp, Control Risks Group, Triple Canopy – is regulated solely by policy agreed between the companies and hiring governments.2 This recent "re-privatization of war", largely the work of Donald Rumsfeld (born 1932) as US Secretary of Defence between 2001 and 2006, superficially recalls the age of the great "military entrepreneurs" of the Thirty Years' War but modern mercenaries are actually auxiliaries rather than substitutes for regular soldiers more closely resembling early modern militias, maréchaussées and invalid companies. However, the governments of the United States and the United Kingdom increasingly rely upon contractors and would be unable to make war without their extensive services.3

When the military comes into contact with civilians, civil-military relations result. The term is normally used pejoratively although outcomes can be positive as well as negative. For instance, the reduction of the British army to civilian control after 1689 established a political principle that has ultimately been adopted by the majority of European states; the failure of the Bourbon monarchy to isolate its army sufficiently from everyday society was partly responsible for fomenting the French Revolution; and during the second half of the 20th century, society has benefited hugely from developments in military technology. The military affected nearly every aspect of civilian life in the world wars of the 20th century, especially between 1939 and 1945 when strategic bombing and invasion extended the experience of combat from the front line to the "home front".4 Civil-military integration was further increased when conscription forced many civilians to become temporary soldiers. From 1945 until 1989, the Cold War and the threat of nuclear confrontation formed a background to nearly all world events.

In peacetime, civil-military relations during the 17th and 18th centuries were largely determined by the fact that national governments were principally war-making machines. Modern militarism, both a political creed and means of social regulation, began in earnest with the absolute monarchies of 18th-century Europe, which organized their states along martial lines. Brandenburg-Prussia under Frederick the Great (1712–1786) remains the archetype but similar systems operated in Austria, Russia and Hesse-Kassel. Although two decades of civil war, regicide and military government had caused the English to develop a strong antipathy towards the professional military, following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 over half the royal revenues were devoured by the army, navy and supporting logistical organizations.5 The adoption of peacetime conscription across most of Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries brought nearly everyone into contact with national martial institutions. When faced with simultaneous requirements to provide an army of occupation in Germany, fight the Korean War and attempt to re-establish the empire, Britain responded by laying aside its long-standing dislike of the military and, from 1947 to 1960, enforced male conscription. Civilians in Benito Mussolini's (1883–1945) Italy, Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union and Francisco Franco's (1892–1975) Spain were governed by regimes that glorified war and consciously militarized society. Since 1945, the lives of people in South Africa, Chile, Spain, Argentina, Portugal, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Greece, Russia, Cuba, the Balkans, China and Eastern Europe have similarly been blighted by military-police states. Civil-military relations have thus touched the majority of human affairs over the past five hundred years.6 A subject of such magnitude cannot be discussed fully in a short article but some general patterns can be discerned by examining two closely-related aspects from which most of Europe suffered during both war and peace throughout the entire period: military accommodation and conscription. On joining an army, recruits relinquish most civil and legal rights and are quickly de-civilianized and, to some extent, de-personalized by "basic training".7 Thereafter, fraternization between soldier and civilian undermines the newly-acquired military attitudes and discipline, a huge problem in mass conscript armies, where civilians temporarily mutate into soldiers for a fixed period of service and, consequently, are rarely completely indoctrinated with the martial ethos.8 To ensure the highest possible state of efficiency, conscripts must be housed separately from civilians in purpose-built accommodation. Shortages of money have often made this only partially possible and few governments have avoided recourse to billeting, a less desirable substitute that enables civil-military contact.

Military accommodation

Until the second half of the 17th century, armies were largely mercenary and temporary, existing only in time of war. Peacetime billeting – the lodging of soldiers on civilians – did not become a major problem in western Europe until the second half of the 17th century, when most European governments raised quasi-national standing armies without the financial resources to maintain them adequately.9 In the widespread absence of barracks, soldiers had to be quartered in private houses, inns and taverns, stables

The artillery and engineers were the first to abandon billeting and move to accommodation built within their academies, training establishments and fortresses.10 Next, although still accompanying the sovereign on his travels, by 1700 regiments of royal guards were semi-permanently located within capital cities. This was certainly the case in London and Paris. Meanwhile, the bulk of the "line infantry" was usually lodged in fortifications and towns while cavalry took quarters in the countryside in order to feed their horses. In England, the foot soldiers were stationed in the main ports and garrison towns: Berwick-upon-Tweed, Hull, Chatham and Rochester, Westminster, Portsmouth, the Isle of Wight, Plymouth, Falmouth, Chester and Carlisle. The cavalry was dispersed across the Home Counties, Midlands and East Anglia. A similar distribution was practiced in Prussia and France, where the infantry was concentrated in fortress towns along the east and north-east frontiers between Dunkirk and Briançon while the cavalry was scattered throughout the interior.

In England, billeting briefly became a political issue during the early years of the reign of Charles I (1625–1649). The Petition of Right (1628)

There were some barracks in early Stuart England, usually old, empty, decrepit buildings. During the English Civil Wars, the Parliamentary army regularly desecrated Anglican churches, especially the more spacious cathedrals, to stable horses and lodge soldiers. After the Restoration in 1660, the English standing army owned some living space in the Tower of London, the Savoy in Westminster and the principal garrisons, but over half the troops had to be billeted. Barracks were built in the principal towns in Ireland following the end of the Jacobite War in 169112 and in Scotland after Culloden in 1746 – principally Fort William and Fort Augustus – but these were police posts and blockhouses intended to intimidate restive civilians. Uncomfortable civil-military relations caused by frequent neglect of the billeting laws were a constant in the important border fortress of Berwick-upon-Tweed. To solve the problem, the Ravensdowne Barracks were opened in 1721, the first purpose-built military accommodation in England since the departure of the Romans. They housed a battalion of 600 infantry in two, three-storey blocks on opposite sides of a parade square. The rooms, where eight men slept in four double-beds, were arranged around three staircases. Thirty-six officers lived in a pavilion along the third side of the square and the quadrangle was completed by a two-storey office and storehouse block. At first there was neither sick-bay nor kitchen, and the men prepared meals in their own rooms.13 Spurred on by indiscipline in the ranks, anti-militarism among the majority of the population, poor civil-military relations occasioned by infringements of the quartering regulations and the need for sustained, large-unit training, the British army was gradually moved into municipal barracks between 1792 and 1858. In 1822, the Board of Ordnance assumed responsibility from the civilian authorities. Initially, the internal arrangements of the jerry-built, brick sheds were unsatisfactory, with over 30 men sleeping side-by-side on long benches. The Duke of Wellington (1769–1852) ordered tiered, iron bedsteads so that each man had his own berth but barracks remained unhealthily overcrowded. Beds were supposed to be separated by a minimum gap of twelve inches but this was rarely observed: in 1847, 500 men were crammed into the Jersey barracks designed to accommodate 386.14 Lessons from the colonies led to considerable improvements after 1850. Barracks were re-positioned on the edge of towns close to major roads and railways and, more significantly, washrooms and sanitary facilities were introduced. Edward Cardwell's (1813–1886) Army Reforms of 1870 allocated every regiment a dépôt town complete with barracks. Thus, the great majority of the more substantial English towns and cities acquired barracks, greatly reducing civil-military contact.15 Barracks remained communal and fairly primitive until the emergence of a freer and more affluent society during the 1960s led to a crisis in service recruitment. One solution was to make the soldier’s life more attractive by replacing traditional barracks with modern accommodation where each unmarried soldier had his own bed-sitting room complete with sanitary facilities and married men occupied apartments or individual houses. During the last fifteen years, the United Kingdom armed forces have contracted considerably in size resulting in the sale of much of this property while the remaining accommodation has often been poorly maintained. However, during the Second World War barracks and temporary camps proved insufficient for the millions of army conscripts and recourse was made to billeting on private householders, one of the causes of the British army’s poor discipline and training. The Royal Navy and Royal Air Force, both of which were similarly augmented with conscripts, maintained a more professional ethos partly because they were able to house most of their personnel in dockyards, ships and airfields.16

Specialized "camps", complete with barracks, were developed from the mid-19th century to cater for the increasing range of weaponry and provide facilities for the rapid, annual "processing" and training of "classes" of conscripts. France had established several training camps during the 18th century but the first modern, permanent base was opened at Mourmelon ("Camp Châlons") in 1857. During the 1890s, Germany reserved infantry manoeuvre grounds adjacent to existing artillery ranges. Although Britain had a professional army rather than a conscript army, similar training areas were needed: Aldershot was established in 1854–1855

Making use of suitably situated towns and cities, an ordinance of 1544 ordered the establishment of a network of military staging posts, or étapes, each separated by one day's march, on the arterial roads leading from central France to her frontiers and laterally along those borders. The first chain of étapes, down the Maurienne Valley leading to the Italian border, was in place by 1551. Learning from French practice, the government in Madrid created the famous "Spanish Road", a combination of tracks and "staples" that varied according to the season of the year, the weather and the local political circumstances, to support soldiers marching from Milan to the Netherlands via Lombardy, Savoy, Franche-Comté, Lorraine and Luxembourg. It was first used in 1623. A French town designated as an étape received money from the government to create the necessary infrastructure of stores, provisions, transportation and quarters, usually in empty, derelict buildings. The burden of billeting was thereby lessened. After 1623, there were four main lines of military communication: Brittany to Marseilles; Normandy to Languedoc; Picardy to Bayonne; and Saintonge to Bresse. Series of étapes characterized most French main roads by 1700, with civilian provision contractors supplying human and horse feed. In 1778, the Comte de Saint-Germain nationalized the étapes, which were subsequently expanded into a series of magazines under Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821). When troops travelled away from the étapes network, communities were allowed to deduct the cost of billeting from taxation. With the advent of railways in the mid-19th century, the étapes declined in importance but were not finally dissolved until 1870.18

Unfortunately, the étapes network only accommodated soldiers on the march. Castles had always included accommodation for the garrison, and the "artillery fortifications" of Pagan, Coehoorn, Vauban and Dahlberg incorporated barracks. Louis XIV issued several edicts stating that lodging soldiers in barracks was the only means by which military discipline could be maintained and civilians freed from having to share their houses with unwelcome strangers. However, the large costs restricted progress. A number of empty and neglected buildings were assigned for military use but most soldiers not garrisoning fortifications continued to be lodged with private householders. Compulsory free billeting was also occasionally used by states as an instrument of coercion, as demonstrated by the "Dragonades" against the Huguenots, James II's (1633–1701) policy of Catholicisation in England between 1685 and 1688, and the suppression of religious dissent in Restoration Scotland. A new set of imperatives led to an invigoration of French barracks building after 1763. In large towns, bodies of troops already assembled in one place were required to assist the municipal police in fire fighting, controlling riots and protecting markets. In Rouen, the Saint-Sever (1774) and Pré-au-Loup (1780) barracks were built to house a garrison capable of suppressing serious disorder. Elsewhere, in Caen for example, the overt purpose of constructing barracks was to protect the delicate townswomen from the offensive sight and presence of soldiers. In effect, barracks were prisons quarantining soldiers from civilians and many had iron bars across the windows. The great increase in the number of conscripts during the second half of the 19th century and the practice of locating barracks in towns were cited as possible factors in the relative depopulation of the French countryside. In 1906, eight per cent of Breton rural conscripts who had been accommodated in municipal barracks either remained in the town after discharge or returned shortly afterwards. More than one third of French conscripts who had experienced the delights of Paris, Lyons and Marseilles did not want to go home. Revised regulations governing the design of barracks were introduced in 1873: the first new-pattern buildings were opened at Bourges in 1880. They were light, spacious and airy, each man having his own bed. Guardrooms, sickbays, latrines, detention cells and kitchens were all included. The new, more civilized barracks required large areas of land, which inhibited widespread adoption, a problem not restricted to France. In 1939, the Wehrmacht required 953,806 acres to accommodate over one million men

Early modern European states were slow to build barracks because of the expense, even though the alternatives of billeting their soldiers upon the civilian population or employing cantonal systems of recruitment and conscription tended to re-integrate soldiers with civilians. Both Frederick the Great and Maria Theresa (1717–1780) were much exercised by the need to isolate their troops from the pernicious influences of the Enlightenment. Troops would only support absolute monarchy if they were isolated from the ideas current within civilian society. Foreign troops were ideal but, if unavailable, native soldiers sufficed – provided that they were not stationed close to the districts from which they had been recruited. The armies of Brandenburg-Prussia and Austria were mainly lodged with civilians until after the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, when both states gradually transferred their forces into barracks. Prussian barracks contained between 25 and 30 men, each sharing a double bed. Some purpose-built barracks had appeared in Austria prior to 1748 but the majority of men lived in "semi-barracks", usually dilapidated and abandoned houses riddled with lice, fleas and epidemic diseases.20 Billeting on civilians continued and the numbering of houses was introduced in France in 1768 and Austria in 1781 to assist both billeting officers and quartermasters. Those countries that adopted a cantonal system of recruiting, principally Prussia, Austria and Hesse-Kassel, avoided some of the tensions arising from military accommodation. Charles XI of Sweden (1655–1697) solved the problem by placing the soldier firmly within society and making civilians responsible for his housing, employment, material well-being and replacement. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, across much of Europe a proper infrastructure of barracks was essential for the administration of mass conscription, which became the norm after 1850: there were 230 garrison towns in Prussia in 1850 but 330 by 1869.21 In order to inculcate martial values into young, impressionable conscripts within the shortest possible time, the application of strict civil-military separation was essential. Similar principles still apply in those countries that have retained peacetime conscription, although the standard of barrack accommodation has improved immeasurably to bring it into line with the general rise in the civilian standard of living.

Conscription

A volunteer willingly recognizes that his life is both dispensable and expendable, whereas the conscript has no choice but to accept the same conditions. Various forms of conscription have been applied throughout history. The duty to bear arms on behalf of the liege lord lay at the heart of the feudal system. Early modern armies and navies normally conscripted individuals when the supply of volunteers was insufficient, usually during rapid expansion at the beginning of wars or to replace casualties. Criminals, vagrants and the unemployed were all liable to conscription, the former often sentenced to military service in lieu of physical punishment or incarceration.22 The Royal Navy could not have functioned without recourse to the press gang while the galley fleets of the French, Spanish, Genoese, Venetians, Maltese, Barbary pirates and Ottoman Turks remained at sea through the efforts of criminals, religious dissidents, prisoners of war and kidnapped unfortunates.23 Naturally, volunteers were preferred, being generally better motivated than pressed men and less likely to desert, but there were never enough in wartime. To attract recruits, "bounty money", or a signing-on fee, was offered, the value of which varied according to supply. The availability of volunteers depended on the seasons of the year and the cycles of plenty and famine.24 A concentration of casual labourers and unemployed men made towns more productive recruiting grounds than the countryside, and recruitment was always easier in winter when seasonal employment was low. Even during the critical middle years of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697) and the period between 1709 and 1712 in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1715), exceptionally poor harvests temporarily eased recruiting pressures in the French army. Despite efforts to stamp out manifold abuses committed by recruiting officers, François Michel Le Tellier, marquis de Louvois (1639–1691), admitted that "when the king needs men, that is not the time to examine whether they were enrolled in due form".25 To the labouring poor in towns and the peasant in the field, army life was not unattractive: pay was relatively regular; accommodation was usually provided; food was normally made available; plentiful opportunities existed for "moonlighting"; military law, discipline and modes of punishment were no more severe than those in civilian societies; the likelihood of engaging an enemy was remote; and sex and alcohol were readily obtainable from the array of camp followers that trudged behind every army.26 Many joined the army just for bread. Likewise, leaky tents or filthy, cramped barracks were probably similar to the lodgings that the soldier had "enjoyed" before joining-up.

During the 18th century, princes who could not afford mercenaries or ruled populations too small to furnish armies large enough to fulfil their political ambitions, replaced ad hoc variants of conscription with formal and organized systems. The origins lay in the ban and arrière ban of the Middle Ages where lists had been kept of all men fit and able to bear arms. France introduced registers of "naval classes" in 1669 when the manpower demands of Jean-Baptiste Colbert's (1619–1683) naval and colonial expansion outstripped the supply of trained seamen.27 The manning of the French royal militia was regularized in 1688: a roll of all eligible men was compiled from which a selection was chosen by ballot. Sweden improved an already existing system of cantonal conscription in 1682 as part of the Indelningsverket (allotment system), which placed the onus for manning the royal army on groups of farmers renting crown lands.28 In 1733, Prussian territories were divided into military districts, or "cantons", and all male births were entered into registers from which recruits were selected annually. Hesse-Kassel copied this scheme in 1762 creating an army that Landgrave Frederick II (1720–1785) rented to other rulers, producing enough revenue to beautify his capital, Kassel. Austria followed suit in 1781 in an effort to achieve military parity with Prussia. All these systems attempted to reduce the economic deadweight of the army by calling cantonists to the colours for a period of initial instruction before allowing them to return to their civilian occupations interrupted only by short periods of annual refresher training and mobilization.29

Cantonal conscription was highly selective. Only the unemployed and urban or rural labourers were recruited; the clergy, the nobility, the professions, the commercial middle classes and even some categories of farm labourers were exempt. Modern, universal, male conscription originated from Lazare Carnot's (1753–1823) levée en masse of 1793, which advanced the concept that, in time of danger, it was the duty of every man to help defend the state in return for the benefits of citizenship, effectively a new form of feudalism.30 However, after an initial enthusiastic response, voluntary recruitment fell away, necessitating Jean-Baptiste Jourdan's (1762–1833) law of 1798, which introduced compulsory, universal conscription for all Frenchmen between the ages of 20 and 25. Universality proved unattainable: certain social classes still received exemptions and the draft could be evaded by the purchase of substitutes or flight. Nevertheless, when extended to countries under French occupation, Jourdan's law provided an army large enough to satisfy Napoleon's gluttony for human life.31 Abolished in 1814 at Allied behest, conscription was reintroduced in 1818 by Laurent de Gouvion-Saint-Cyr's (1764–1830) law. However, the ideal of universality had slipped further and the new system belonged more to the 18th century than post-Revolutionary France. Each year, the young men in the class called up drew lots to decide who had to endure seven years' military servitude. Substitution was permissible – babies could be insured from birth against drawing an unlucky number – but the conscript had to provide his own replacement and serve in person if no-one else could be found.

Whereas the French Revolutionary governments risked arming the people to oppose reactionary monarchies, those reactionary monarchies hesitated to arm their own people for fear of revolution. After defeat at Jena and Auerstedt in 1806, Prussia had no option but to reform its entire military system by introducing universal, short-service conscription and by opening the officer corps to the middle classes.32 However, the Prussian "nation-in-arms" failed to blossom into a "citizen army" when the Congress of Vienna (1815) restored the pre-1789 international order: compulsory military service continued but in a royal army rather than a permanent, national formation. One of the legacies of French occupation was the adoption of conscription by ballot in many German states until unification under Prussia in 1870/1871 resulted in the adoption of compulsory military service. In France, selection by ballot was abolished in 1889, but universal, compulsory military service was introduced only in 1905. Young men served for two years, then entered the reserves until the age of 34, before passing into the home army until they reached 40 years of age. Poor health provided the sole grounds for exemption. To compensate for a falling birth-rate, first-line service was extended to three years in 1913. In 1914, France immediately mobilized 780,000 men, equating to one-in-26 of her male inhabitants, while Germany's ratio was one-in-76 yielding an army of 850,000. During the 1914–1918 War, eight million Frenchmen served in the armed forces, or two-in-five of her male population, and 15 million Russians were drafted. Even Great Britain, under the pressure of war, introduced compulsory male conscription from 1916 to 1919.

Between the two World Wars, the duration of military service reflected the political situation. In France, it was 18 months in 1923, one year in 1928 and two years in 1936. Almost all belligerents in the Second World War employed obligatory military service but, except for the extreme case of Germany in 1944 and 1945, mobilized proportionately fewer men than in 1914–1918 because of the need to reserve labour for vital war production. Between 1941 and 1945, Britain conscripted 1,700,000 women into industry, agriculture, the police and non-combatant roles in the armed forces.![Female Factory Workers in Britain IMG Kirkby factory workers around a bomb, black-and-white photograph, Great Britain, unknown date [between 1939 and 1945], unknown photographer; source: National Museums Liverpool, http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/nof/blitz/0700_info.html.](./illustrationen/civil-military-relations/female-factory-workers-in-britain/@@images/image/thumb)

Universal military service was widely adopted during the 19th century for a number of reasons. The legacy of Napoleonic occupation was influential, while the scale of warfare steadily increased, thereby necessitating ready access to large cohorts of trained men. Some European states were newly formed – Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Norway – and conscription made societies more homogeneous and cohesive by inculcating nationalism and diluting regional and provincial influences. Conscription was also educative with many learning to read and write during national service. It was said that the Austro-Hungarian army was the sole expression of nationalism within a particularly rambling and incoherent state. Certainly, its combat performance on the Italian front (1915–1918), when heavily outnumbered, demonstrated considerable unity and common purpose.33

The need to foster national identity, as well as dangers to state security caused by the Second World War and subsequent Cold War, persuaded most European countries to retain conscription after 1945. However, the formation of NATO in 1949,

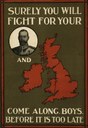

Although conscription has never been popular, even democratic governments have consistently been able to persuade people of its necessity. Between Dunkirk in 1940 and Operation Overlord in 1944, most of the British conscript army took no active part in the war but moved from camp to camp within the British Isles, preparing for the eventual invasion of mainland Europe. The men were bored, hated both Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874–1965) and the war but were sufficiently conformist to obey the law and believe the propaganda. The reintroduction of conscription in 1947 was deeply loathed and resented yet a conservative, war-weary and demoralized population did not revolt.35 Conscription built some fragile bridges between soldier and civilian but its eclipse will be mourned by few and the military will again retreat into introspective. Therein resides some guarantee of political stability, although the politicization and right-wing leanings of many European officer corps are frequently underestimated. The received wisdom is that armies reflect their parent societies. It is assumed that Europe is now federalist rather than nationalist, anti-war, anti-armed forces and anti-conscription. So great has the disassociation between the military and civil society become that the recent British Labour government under Tony Blair (born 1953) and Gordon Brown (born 1951) – continued by David Cameron’s (born 1966) coalition administration – mounted a "love the British armed forces" campaign to justify unpopular and irrelevant wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the cant intensifying as the casualty rate increased. Every military death was reported in the media; each returning corpse greeted with full televised pomp; every soldier, whether cook or machine-gunner, dead or injured, suddenly became a "hero"; and the connections between the armed forces and the royal family were shamelessly exploited. Instead of modern British soldiers skulking around in civilian clothes lest they became targets for ridicule or terrorists, they are now encouraged to wear uniform in public. This propaganda initiative appears to have achieved significant and rapid results amongst a fickle and gullible public that knows nothing of the realities of war but nothing fundamental has changed. The British army has always been tolerated, even praised, when fighting overseas but the bogus, skin-deep popularity evaporates as soon as the soldiers return en-masse to the British Isles. The army is then required to disappear, wheeled out only for the theatre of state and ceremonial occasions, revealing the true depth of the civil-military divide.36 Within the British Isles, the military remains a mere servant of democratically-elected governments.37

Conclusion

Since 1500, the degree of civil-military separation has varied. War became more "popular" during the religious wars between 1520 and 1648 and civil-military differences consequently became less pronounced until the advent of regular, uniformed, professional armies in the second half of the 17th century re-established a clearer separation. The adoption of compulsory male military service during the 19th and 20th centuries again narrowed the military-civil divide. Since 1991 small, professional, more cost-effective forces have gradually replaced mass conscript armies, leading to a re-sharpening of civil-military segregation.