Lingua franca as a linguistic concept

The term lingua franca (Italian: “Frankish language”) dates back to the Middle Ages. In a narrower sense, it refers to a trade language that emerged in the eastern and southern Mediterranean as a so-called pidgin language, where it was used as a trade language into the 19th century. Its lexical and grammatical foundations are primarily of Romance origin, with influences from other languages, especially Arabic. In a broader, overarching sense, the term lingua franca (also used in the plural as linguae francae or lingue franche) refers to a commercial language generally used in interactions between different linguistic communities in commerce and transportation, serving as a common linguistic basis

The concept of lingua franca is closely related to several other linguistic concepts.1 These include (internal and external) multilingualism as the use of several languages or linguistic varieties in a specific national, social or communicative context, and plurilingualism as the use of several languages or linguistic varieties by individual persons (e.g. French and Lëtzebuergesch in Luxembourg). In addition, the concept of pidgin or pidgin language includes the lexical and grammatical simplification of a language developed for specific communicative needs in trade and transportation. This language is learned by individuals as a foreign language. When pidgin evolves into a language of its own, not learned as a foreign language but acquired as a first language, a creole or creole language is created (examples can be found especially in former colonies, such as the Caribbean). A mixed language, on the other hand, is not a simplification and independent evolution of a specific language, but the true fusion of several languages into a new common language (an example is Jenisch, a mixture of German, Yiddish, Romani, and Rotwelsch).

Consequently, the lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean should be considered a true pidgin language, influenced by other languages, but not a mixed language in the true sense of the word. A lingua franca, in its broader definition, allows for the following distinctions: It can be an established single language, but also a pidgin or creole, and ultimately a mixed language; it can also be an artificial or planned language like Esperanto. Its primary function is to facilitate or mediate communication in regions where several different languages are spoken; for this reason it is sometimes called the (international) language of trade or science, or the language of diplomacy. Throughout their history, both Latin and French have served as such internationally recognized linguae francae in various communicative domains, each with its own unique characteristics.

Linguae francae and global trade languages

The emergence and use of linguae francae is a phenomenon that is not limited to recent history or to the European area alone. In antiquity, for example, Akkadian, Aramaic, Greek, and Latin were used as supraregional languages of trade in the Near East and the Mediterranean region. Latin continued to be used in Europe during the Middle Ages; in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, Italian in the Mediterranean region and Low German in the North and Baltic Seas developed into important trade languages. After the emergence of Islam, Arabic spread as a lingua franca and trading language from the Near East to Spain and West Africa as well as to Central Asia. There, and in the Pacific region, languages from the Hindi and Malay regions increasingly assumed a similar function, while Chinese already had a longstanding importance here that has continued up to the present.

Since the early modern period, Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch have become important trade languages, especially in contact with South America, southern Africa, and Southeast Asia. Since the 17th century, French has become the international language of diplomacy, while German became the international language of science from the 18th century until the end of the First World War. In Eastern Europe, German is still widely used as a trade language and is currently experiencing a resurgence in southern Eastern Europe. During the Cold War, Russian played a similar role in that region. By the end of the Second World War, English had established itself as the international lingua franca in politics, transportation, economy, and science, while French continued to serve a similar function in West and Central Africa

In the light of these broad outlines, Latin and French must be considered as linguae francae that were in use for two millennia and two to three centuries, respectively. Their importance for the contemporary linguistic situation varies greatly.

Latin as a lingua franca since the early Middle Ages

Latin established itself as a lingua franca with the expansion of the Roman Empire and continued after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in large parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe

Until the 12th century, Latin was the language of the clergy in theology and the Church, as well as in the sciences practiced in the monasteries. At the same time, the use of one or more local languages in the sense of multilingualism in individual regions and plurilingualism of individuals was a widespread phenomenon among wide segments of the European population. The use of the lingua franca Latin thus remains the preserve of only a few privileged groups predominantly in the area of written language (with the exception of the liturgy, for example). In the 16th century, however, the status of Latin as the lingua franca of the Church began to suffer increasingly in the 16th century. Although the newly founded Protestant Church retained Latin as the language of theology, it introduced the use of individual vernacular languages for preaching. This is a measure that the Catholic Church would not take until centuries later. Latin is still the official language of the Roman Catholic Church in the Vatican and throughout the world.

Since the 17th century, Latin has also been losing ground in science, which has been gradually secularized since the late Middle Ages. This is due to at least two developments: First, various applied sciences and diverse technical disciplines using other, local languages became increasingly important. These include seafaring and trade, which were strongly influenced by Dutch; mining, which has vocabulary elements from German in many European languages; and banking, whose language is significantly influenced to this day by Italian. In all these cases, new national technical or scientific languages emerged alongside Latin, some of which themselves became new linguae francae. In the course of the second development, the Latin language also lost importance in its long-established scientific areas of communication. This shift began in the German-speaking world around the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries in disciplines like philosophy and law and ended during the 19th century in mathematics and theology.

Starting in the early modern period, Latin as a language of science was supplanted by various individual national languages – first in Italy, France and England; later in Germany and Poland, for example. Despite this European-wide process, it would be wrong to assume a complete loss of the Latin language. Apart from being used in the church, Latin is still the language of academic publications and of doctoral theses; in addition, many scientific nomenclatures are based on Latin (and also Greek) vocabulary (such as those used in zoology, botany

For many centuries, however, Latin was not only used in the Church, science, and education. It was historically also the language of diplomacy, typically conducted by the nobility. But even in this sphere, a transformation is seen in the early modern period. In the wake of widespread linguistic patriotism and growing skepticism towards Latin, which since the era of humanism had been strongly oriented towards antiquity (the Middle Ages witnessed numerous simplifications akin to pidginisation and partial creolization of Latin), individual national languages developed into supra-regional and widely used literary languages. These languages were drawn on not only in belles-lettres but also in scientific literature (at the end of the 15th century almost all writings appeared in Latin, at the end of the 17th century only about half; nevertheless, important scientific works continued to be authored and published in Latin well into the 19th century). With the rise of national literary languages, at least since the 17th century, Spanish and later French assumed this role (for more details, see the following section).

Jan-Dirk Müller reaches the following conclusion in view of such developments in the Latin language from the Middle Ages to modern times:

As a scientific language, it was superior to all individual languages, although limited to certain types of knowledge. As a technical language, it was at best complementary to a largely oral vernacular practice, supplementing it with written elements. As a vernacular, it was tied to particular groups and institutions. As a literary language, it was confined to a narrow educational elite.3

French as a lingua franca since the early modern period

By the beginning of the 17th century at the latest, various literary languages based on regional vernaculars had started to emerge in Europe. This process was supported by individual academies or societies – for example in Italy by the Accademia della Crusca, founded in Florence in 1583

After the Thirty Years' War and the Peace of Westphalia (signed in 1648 at Münster

Thanks to France's rich history of conquest and colonization, the French language spread to North America (Canada, Louisiana

Nonetheless, the decline of French as a lingua franca on the European continent began at the turn of the 19th century. Even though the reorganization of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars was negotiated in French at the Congress of Vienna (1814–15),

By the end of the Second World War, the United States of America assumed this role, laying the foundations for the emergence of English as an international lingua franca. It achieved global importance not only in diplomacy, technology and science, but also in the economy and day-to-day life.5 Critical to this development was the collapse of the Soviet Union, which also led to the decline of Russian as a lingua franca in many countries of the so-called Eastern Bloc. Despite France’s intensive efforts, it largely failed to revive the use of French in this region, which is also experiencing a decline globally. Thus, while Latin continues to have a marked influence on European culture and language to this day, the “Versailles model” proved relatively short-lived, despite its significance. In the history of language and ideas, the French Enlightenment and French Revolution were finally more influential.

Latin and French in German linguistic discourse in the 17th and 18th centuries

The tension that existed in the 17th and 18th centuries between the use of Latin and French as linguae francae may be reconstructed through the linguistic discourse of the German-speaking world. During the Baroque and Enlightenment periods there was a strong desire to develop a national literary language.6 But this development was accompanied by an intense debate over the old European lingua franca, Latin7, and the new lingua franca, French8. At the end of the 17th century, two minor works in German by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716)[

In his programmatic work Ermahnung an die Teutsche, ihren Verstand und Sprache besser zu üben, written in 1682 and first published in 1846, Leibniz elucidates no less than five reasons for the persistence of Latin in the German-speaking world. First of all, many contemporary scholars believed that scientific deliberation could only be conducted in Latin or Greek (or feared that opting for another language, such as German, would quickly expose them to accusations of lacking relevance). Leibniz points to other reasons for Latin’s endurance: the aftermath of the Thirty Years' War, which had devastated the German-speaking region culturally, linguistically, economically, and politically; the absence of a common capital for the German-speaking region as a political, economic, and cultural center; the division into a Roman Catholic and a Protestant-Evangelical church that was more than just confessional; and, finally, the limited support for the German language (which was modest despite the 17th-century German language societies).

Leibniz eventually links these considerations to the demand that German be developed into a literary or scientific language. In his Unvorgreiffliche Gedancken, betreffend die Ausübung und Verbesserung der Teutschen Sprache

In the context of Latin’s gradual displacement as the lingua franca and the introduction of German as the language of literature and science, the establishment of French as the lingua franca was, unsurprisingly, also a source of debate in German linguistic thought. Linguistic-cultural stereotypes were employed to an even greater extent than in the case of Latin. French was repeatedly ascribed qualities of sophistication and politeness in contrast to the alleged ponderousness of German. Conversely, the use of German was seen to ensure objectivity in contrast to the perceived bias and dishonesty of French.

Ultimately, it becomes clear that the use of both linguae francae in the German-speaking world was not unbiased, even within the social circles in which they are used to varying degrees in academia, the church, administration, business, and diplomacy. Moreover, we see that the partial shift from Latin to French as the lingua franca, especially in the German-speaking world, stood in considerable tension with the emergence of other national literary languages.

Latin, French, English – and Chinese?

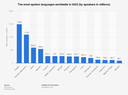

The Versailles period is largely characterized by the loss of Latin as the lingua franca and the ascendancy of French. However, this general observation needs qualification – not least with regard to English as the lingua franca of the present (see Table 1).

Table 1: A comparison of the linguae francae Latin, French, and English.

|

Lingua franca |

Latin |

French |

English |

|

Time period (duration) |

Antiquity to 17th or 18th century |

17th to 20th century |

19th century to present |

|

First/foreign language |

Since the Middle Ages only as a foreign language |

First and foreign language |

First and foreign language |

|

Domains |

Theology, science, administration, diplomacy |

(Applied) science, education, diplomacy |

All international communication |

|

Reason for establishment |

Overlapping communication between different linguistic regions in Europe |

Establishment of national literary languages under the supremacy of France |

Supremacy of Great Britain and the USA (politics, economy, etc.) |

|

Reason for loss |

Establishment of national literary languages (e.g. in Italy, France, Germany) |

Competition from English-speaking nations (Great Britain and the USA) |

Growing importance of China and India (politics, economy, etc.)? |

|

Surviving |

Theology, nomenclatures, Europeanisms |

(Partial) education and diplomacy |

(Currently) in all areas of life |

Latin has been used as a lingua franca for over 2000 years, French for about 300 years, and English for about a century and a half. Like English, French is not exclusively spoken and written as a foreign lingua franca, thus creating an imbalance in the verbal competence of its users and potentially leading to a linguistic hegemony among certain population segments. Latin, on the other hand, has been used exclusively as a foreign lingua franca since the Middle Ages (given its evolution, it is hardly appropriate to call it a "dead language").

The reasons vary for the establishment of the three linguae francae. While Latin assumed the role of a linguistic umbrella over many regions of Europe in antiquity and maintained this role through the Middle Ages and into modern times, French was ultimately able to develop this function because of two developments – the establishment of numerous national literary languages in Europe9 and the rise of France as a political, economic, and cultural powerhouse after the Peace of Westphalia. English owes its relatively recent role as a lingua franca to the growing preeminence of English-speaking nations, first Great Britain and then the United States of America.10 It is worth noting that the global use of English extends to all areas of international communication, whereas Latin and French have always been reserved for certain, if not exactly the same, communication domains.

The establishment of national literary languages may ultimately be seen as the reason for the decline of Latin as a lingua franca. Nevertheless, it has remained in certain areas of theology and science, and persisted as the semantic core of many Europeanisms in the vocabularies of different European languages. In contrast, French gave way to English as a lingua franca due to the growing dominance of English-speaking powers. As to the future of the now globally dominant English lingua franca, we can only speculate. At present about 400 million people use English as a first language and about 1.5 billion as a second language, and in some areas the international literature in English accounts for 90 to 100 percent. However, its importance could diminish in the coming decades in view of the political and economic growth of China and India and the influence of their languages