Introduction

In spite of the considerable commonalities that Christianity and Islam have shared and although there have been several periods of cordial relations and cultural exchange, the history of interaction between European Christian societies and their Middle Eastern Islamic counterparts has also been one of conflict and aggression, of polemics and demarcation. The Muslims, who in the early Middle Ages conquered the Syrian and North African provinces of the Byzantine Empire, as well as Spain and Sicily, and in the late Middle Ages extended their rule to the Balkans and Eastern Central Europe, were not only a political and military problem for the states of Europe, but also constituted a religious and cultural challenge to Latin Christians.1

In spite of the considerable commonalities that Christianity and Islam have shared and although there have been several periods of cordial relations and cultural exchange, the history of interaction between European Christian societies and their Middle Eastern Islamic counterparts has also been one of conflict and aggression, of polemics and demarcation. The Muslims, who in the early Middle Ages conquered the Syrian and North African provinces of the Byzantine Empire, as well as Spain and Sicily, and in the late Middle Ages extended their rule to the Balkans and Eastern Central Europe, were not only a political and military problem for the states of Europe, but also constituted a religious and cultural challenge to Latin Christians.1

This conflict-laden relationship is one of the reasons why Islam has been perceived and constructed as probably the most important "other" of Europeans and Latin Christians since the Middle Ages. That is to say, Europeans – or Latin Christians – continuously determined, redefined and further developed their own identity in contrast to Islam and Muslims. As a result, different discourses of alterity arose defining the religious, cultural and social dichotomy between Europeans and Muslims. By tracing the patterns in which Islam was perceived and interpreted, this article analyses the construction of "self" and "other" as a discursive process. The analysis focuses on three chronological periods. Firstly, it discusses the "image of the Turk" in the period from the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 to the end of the 16th century which was characterized by fear and religious discourses. Then, the article focuses on the transformation of this image in the period around 1700 and the new patterns of perception in the age of Enlightenment. Thirdly, the perception of Islam and Muslims – or "Orientals" and the "Orient" – in the 19th century, the age of European Imperialism, will be dealt with. Throughout, the central object of enquiry is the construction of difference – cultural, religious, political and social – between Europe and Islam and the conceptualization of Islam and Muslim societies as the "antithesis" of Europe. The primary category in which Muslims and Islam were perceived as the "other" changed over time: Muslims were at times simply referred to as "Turks" and Islam was at times subsumed under the broader category of the "Orient".

The construction of alterities, that is, the construction of "the other", of "the alien" in order to define "the self", "one's own", is not exclusive to Europeans. All larger communities define themselves to some degree in contrast to others. The construction of alterity usually occurs by means of dichotomies, that is, asymmetrical pairs of terms that are organized by means of oppositional structures and binary central terms.2 The construction of an alterity in opposition to "one's own" usually implies a perception of the superiority of the latter. This superiority can be defined in religious, moral, intellectual or technological terms.3 Superiority can also be perceived as existing in a combination of areas.

Alterity – and by extension its opposite, identity – is constructed by discourses, that is, by linguistically (literary/textual material) and/or pictorially (visual/iconographic material) created contexts of meaning and ascriptions of meaning.4 Although discourses are distinguished by a certain stability, they are nevertheless subject to continuous change as they are adapted to changing needs and circumstances. Some discourses can prevail and achieve a hegemonic dominance, while others remain marginal. Discourses of alterity and identity that are characterized by binary central terms carry numerous topoi, stereotypes and clichés. They invariably exhibit great endurance5 and wane slowly. Such discourses of alterity are manifested in very different genres of text: travel literature, the records of diplomatic missions, scientific treatises, literary texts, sermons, etc.

The Image of Islam in the Era of the "Turkish Menace"

The conquest of the Byzantine metropolis Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in May 1453 came as a shock to Christian Europe, especially to Italy.6 Although the Byzantine Empire had not been a great power for some time, the prestige and importance of Byzantium as the "Second Rome" was still great. Reports of the fall of Byzantium spread rapidly and strengthened the negative image of Muslims that had prevailed in Europe since the crusades. These reports contained detailed descriptions of the atrocities committed during the conquest (so-called "Turkish atrocities"), which subsequently entered the discourse on the Ottomans in the form of stereotypes and shaped the perception of a "Turkish menace"7 (Türkengefahr) as well as the "dread of the Turks" (Türkenfurcht) fed by it.8 These reports were very quickly used as propaganda in the call for a new crusade, now understood as a war against the Turks. Already in 1454, Cardinal Enea Silvio Piccolomini (1405–1464), who subsequently became Pope Pius II (1458–1464)[

came as a shock to Christian Europe, especially to Italy.6 Although the Byzantine Empire had not been a great power for some time, the prestige and importance of Byzantium as the "Second Rome" was still great. Reports of the fall of Byzantium spread rapidly and strengthened the negative image of Muslims that had prevailed in Europe since the crusades. These reports contained detailed descriptions of the atrocities committed during the conquest (so-called "Turkish atrocities"), which subsequently entered the discourse on the Ottomans in the form of stereotypes and shaped the perception of a "Turkish menace"7 (Türkengefahr) as well as the "dread of the Turks" (Türkenfurcht) fed by it.8 These reports were very quickly used as propaganda in the call for a new crusade, now understood as a war against the Turks. Already in 1454, Cardinal Enea Silvio Piccolomini (1405–1464), who subsequently became Pope Pius II (1458–1464)[ ], delivered a speech as imperial legate at the Reichstag (Imperial Diet) in Regensburg advocating a war against the Turks.9 As one of the most influential orators of his time, he pointed out the global historical importance of the "Turkish menace", the ecclesiastical, military and strategic significance of Constantinople, all the while appealing to the fundamental moral and political values of the Christian princes. Enea Silvio used this "recyclable speech" in revised form at other imperial diets, and it was widely distributed as a manuscript and as a printed text.10

], delivered a speech as imperial legate at the Reichstag (Imperial Diet) in Regensburg advocating a war against the Turks.9 As one of the most influential orators of his time, he pointed out the global historical importance of the "Turkish menace", the ecclesiastical, military and strategic significance of Constantinople, all the while appealing to the fundamental moral and political values of the Christian princes. Enea Silvio used this "recyclable speech" in revised form at other imperial diets, and it was widely distributed as a manuscript and as a printed text.10

In the context of the fall of Constantinople and the resulting papal efforts to launch a new crusade against the Turks, Italian humanists conceptualized Europe as an entity with which one could identify.11 Flavio Biondo (1392–1463) was particularly important in this process. Even before the fall of Constantinople, he had revised the history of the crusades, particularly that of the First Crusade during which Jerusalem was conquered in 1099, as well as the appeal by Pope Urban II (1035–1099) in Clermont in 1095 that had led to this crusade. In Biondo's depiction, the First Crusade took on the character of a pan-European project rather than an undertaking of the Franks, as medieval sources described it. He defined Latin Christianity as a European Christianity and drew a connection between the crusades and the war against the Turks, depicting both as an effort to repel a menace that threatened Europe from the outside. The First Crusade was thus re-interpreted as a successful defensive enterprise undertaken by the whole of European Christendom and, in this form, it contributed to the construction of a European identity and the cultural-religious self-reassurance of Europeans.12 In this way, the new interpretation of this enterprise played a specific role "für die Wahrnehmung und Einordnung der osmanischen Expansion, für ihre Apperzeption als eine die gesamte lateinische Christenheit bedrängende Türkengefahr und für die Ausbildung des Deutungsmusters 'Europa und die Türken'."13 The numerous calls for a crusade by pope Pius II against the Ottomans14 also became an important medium that shaped and spread ideas of Turks and Muslims as the enemies of Europe.15 Pius II addressed his calls for a crusade to a united Christendom and ignored, as did Flavio Biondo, the divide between Eastern and Latin Christianity. He argued that Christians had often been attacked by unbelievers in Asia but that they were now beset by the Turks in their very own territory of Europe. Jerusalem, having been the goal and place of expectation of salvation history during the crusades, now declined in significance while the importance of "Europe" grew.16

From the mid-15th century, it became customary to equate Muslims with Turks. When early modern texts speak of someone having "turned Turk", it means that he has converted to Islam. The ethnic category "Turk" was thus synonymous with the religious category "Muslim". This linguistic usage was largely equivalent to the ethnic description of Muslims as "Saracens" in the Middle Ages,17 a term that fell out of use during the Early Modern period. The opposing pair of (European) Christians vs. Turks now replaced the medieval duality of Christians vs. (pagan or heretical) Saracens.18 In the construction of this opposing pair, the question of the origin of the Turks played an important role. Trying to answer this question, the Italian humanists proposed two contradictory hypotheses. One stated that the Turks were descended from the Trojans, a theory derived from the similarity of the terms "Turci" and "Teucri" (for Trojans). This hypothesis was gradually dismissed because it associated the Turks with the Europeans since the ancient Romans also claimed Trojan descent.19 A second hypothesis more suitable for depicting the Turks as strangers and "others" established itself towards the end of the 15th century. This hypothesis proposed a Scythian origin of the Turks. This was well suited to the purpose of presenting the Ottomans as barbarians who had nothing in common with Rome, Christianity and Europe because the ancient tribe of equestrian nomads known as the Scythians were associated with the whole repertoire of barbarism: they were depicted as uncivilized, cruel, licentious and utterly repulsive.20 Again, Flavio Biondo and Pius II played central roles in developing and distributing this theory.21

In the writings and speeches of mid-15th-century Italian humanists, "Europe" was conceptualized as an entity that stood in sharp contrast to the Turks. The tracing of the origin of the Turks back to the Scythian barbarians, the re-interpretation of the First Crusade as a European endeavour that served to defend Europe against the barbarians, and the transfer of the political and moral responsibility to "Europe" as a whole (as a "Fatherland", even) in anti-Turkish war rhetoric22 – all this contributed to a conceptualization of "Europe" as an entity with which Europeans could identify. In this way, in opposition to the Turks, "Europe" was assigned a significance that the term had never had before.

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the next important event with a decisive impact on the discourse of the Turks was the (unsuccessful) first siege of Vienna by the Ottomans in the autumn of 1529 . The Ottoman attack, which should be viewed in the context of the Ottoman-Habsburg contest for supremacy in Hungary and related border conflicts, was not an important event from the Ottoman perspective. It was, however, an episode in the rivalry between two empires claiming universal rule. Both the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500–1558) and Sultan Süleyman I (ca. 1494–1566)[

. The Ottoman attack, which should be viewed in the context of the Ottoman-Habsburg contest for supremacy in Hungary and related border conflicts, was not an important event from the Ottoman perspective. It was, however, an episode in the rivalry between two empires claiming universal rule. Both the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500–1558) and Sultan Süleyman I (ca. 1494–1566)[ ] styled themselves as rulers of the End Times, elevating the Habsburg-Ottoman rivalry to an apocalyptic level.23 Another important context in which the first siege of Vienna should be viewed is that of the split of Latin Christianity during the Reformation.

] styled themselves as rulers of the End Times, elevating the Habsburg-Ottoman rivalry to an apocalyptic level.23 Another important context in which the first siege of Vienna should be viewed is that of the split of Latin Christianity during the Reformation.

The first siege of Vienna released a veritable flood of publications on the Turks (so called Türkendrucke, or "Turkish prints" ) in the German-speaking countries and other parts of Europe.24 The spread of the new printing press, which roughly coincided with the Ottoman expansion towards Central Europe, was an important precondition – along with the "Turkish menace" and the "dread of the Turks" – for bringing about the early modern discourse on Islam. The new printing techniques resulted in a densification of communication that permitted the spreading of a particular image of Turks and Muslims within a relatively short period of time over large distances.25 The printing press carried the "dread of the Turks" from the immediate border areas that had already suffered recurring military campaigns and raids since the late-15th century – especially by Ottoman auxiliary troops – into the Holy Roman Empire and beyond.26 Prints on the "Turkish menace" described alleged and actual war atrocities in bright colours; often apocalyptic motives were woven in.27 The Turks appeared as an imminent and great danger to the social, political and religious order, a danger to which all social groups were exposed. In the Habsburg hereditary lands, but also in other parts of the Empire, the "dread of the Turks" and the "Turkish menace" were used in the 16th century by the secular and ecclesiastical authorities for political and propaganda purposes.28 Propaganda in the form of pamphlets

) in the German-speaking countries and other parts of Europe.24 The spread of the new printing press, which roughly coincided with the Ottoman expansion towards Central Europe, was an important precondition – along with the "Turkish menace" and the "dread of the Turks" – for bringing about the early modern discourse on Islam. The new printing techniques resulted in a densification of communication that permitted the spreading of a particular image of Turks and Muslims within a relatively short period of time over large distances.25 The printing press carried the "dread of the Turks" from the immediate border areas that had already suffered recurring military campaigns and raids since the late-15th century – especially by Ottoman auxiliary troops – into the Holy Roman Empire and beyond.26 Prints on the "Turkish menace" described alleged and actual war atrocities in bright colours; often apocalyptic motives were woven in.27 The Turks appeared as an imminent and great danger to the social, political and religious order, a danger to which all social groups were exposed. In the Habsburg hereditary lands, but also in other parts of the Empire, the "dread of the Turks" and the "Turkish menace" were used in the 16th century by the secular and ecclesiastical authorities for political and propaganda purposes.28 Propaganda in the form of pamphlets and other texts which were imparted by the imperial chancellery was primarily directed at the nobility and clergy as representatives of the estates and was intended to help raise funds for the war against the Ottomans. Through the nobility and the clergy, the peasants were influenced indirectly by this propaganda, in which sermons played a particularly important role.29 The discourse on the "dread of the Turks" could be used for various goals. It could be used to legitimate tax levies ("Turk taxes" and war taxes), to promote obedience towards, and trust in, the authorities, and to control the estates. It could also be used to promote piety and behaviour conforming to the rules of the Church. Seen in this way, the propagandistic and political instrumentalization of the "dread of the Turks" played a major role in stabilising the political and social order.30

and other texts which were imparted by the imperial chancellery was primarily directed at the nobility and clergy as representatives of the estates and was intended to help raise funds for the war against the Ottomans. Through the nobility and the clergy, the peasants were influenced indirectly by this propaganda, in which sermons played a particularly important role.29 The discourse on the "dread of the Turks" could be used for various goals. It could be used to legitimate tax levies ("Turk taxes" and war taxes), to promote obedience towards, and trust in, the authorities, and to control the estates. It could also be used to promote piety and behaviour conforming to the rules of the Church. Seen in this way, the propagandistic and political instrumentalization of the "dread of the Turks" played a major role in stabilising the political and social order.30

The image of the Turks in the 16th century was replete with topoi and stereotypes. Texts that were not religious (or only vaguely religious) in tone disseminated primarily the topos of cruelty. The descriptions of Turkish atrocities (murder, rape, carrying off captured Christians, destruction, arson, plunder, desecration of churches, etc.) were used to engender a willingness to fight the Ottomans.31 These could also be combined with biblical motifs, such as the iconography of the Massacre of the Innocents at Bethlehem.32 The Turks and, therefore, Muslims were thus depicted as the incarnation of evil.33 Such frightening images of the "archenemy of Christianity" not only circulated in the Holy Roman Empire, Italy and other territories bordering the Ottoman Empire, but in the rest of Europe as well. This is due to the fact that the topic of the "Turkish menace" found its way into publications all over Europe in the 16th century.34 Although western Europe was never directly threatened by Ottoman armies, "[wich] die in der französischen Bevölkerung verbreitete Einstellung nicht wesentlich von dem traditionell abendländischen 'Türkenbild' einer totalen Perhorreszierung ab".35 Comparable negative images also circulated in England,36 although there the image of the Turks as enemies of the Christian faith existed beside a more positive view that considered the Ottoman Empire as a potential ally against the Catholic powers and as an example to follow in state policy. The discourse that drew a connection between Protestantism and Islam because of their shared rejection of the worship of images played a role in this regard.37

The political and military discourse of the "Turkish menace" of the 16th century was supplemented, expanded and decisively influenced by the religious or theological discourse on Islam and the Turks. There was no unanimity among theologians on how to interpret Islam as a practice of faith. The interpretation derived from the medieval scholastic tradition that considered Islam a Christian heresy38 prevailed, but it was opposed by a tendency to interpret Islam as a secta or lex in its own right and, therefore, as a pagan rite that had parted ways with Christianity. As a third option, theologians of the 16th century could speak about Islam without addressing the question of "heresy or pagan rite?"39 The religious-theological discourse of alterity that unanimously regarded Islam in a negative light – though for different reasons – and presented it as something diametrically opposed to Christianity could be developed from all three opinions mentioned above. Thomas Kaufmann has shown how German – mostly Protestant – theologians, starting with the basic assumption that Islam was a "diabolically perverted derivative" of their own faith, presented the Islamic religion as the "Church of the Antichrist"40 that turned Christian belief into its opposite and that tried with cunning and hypocrisy to tempt Christians to give in to the devil. Similarities between Islam and Christianity were described as superficial or as perversions of the latter.41 Islam was thus viewed in the context of the coming of the End Times; it was considered a necessity of salvation history, and Christians could rest assured that Islam would perish on Judgement Day. The conversions that took place in the territories conquered by the Ottomans challenged the Christians' concept of themselves and fitted into the "Gesamtbild des Christentums als einer eminent bedrohten Religion",42 but they also seemed to confirm the apocalyptic events. Only those of weak faith, the uneducated and primitive masses, could be easily seduced by the Antichrist, while the faithful few could rest assured of their salvation.43

This belief regarding the role assigned to Islam and the Ottoman Empire in salvation history could not only be used to call for resistance against the Ottomans, but was also as a weapon in the internal disputes among Christians during the Reformation. The opposing confession could be "Turkified" by relating it and its teachings to Islam and presenting them as equally dangerous to one's own belief . Martin Luther (1483–1546)44 equated the pope with "the Turk" by drawing analogies between some elements of Catholic and Islamic dogma. The Reformed Church was also accused by Lutherans of having affinities with Islam. On the other hand, Catholic authors polemicized against Lutherans as the "new Turks" or blamed them for the successes of the Ottomans. Furthermore, individual moral and other shortcomings could be "Turkified".45 The religious-theological discourse of alterity that turned Muslims into the antithesis of European Christianity – or, more accurately, of one's own denominational group – created new images of the self that helped to build and strengthen identity. The image of "the Turk" as the enemy became an integral component of the europäische Abgrenzungsidentität ("European identity of delimitation").46

. Martin Luther (1483–1546)44 equated the pope with "the Turk" by drawing analogies between some elements of Catholic and Islamic dogma. The Reformed Church was also accused by Lutherans of having affinities with Islam. On the other hand, Catholic authors polemicized against Lutherans as the "new Turks" or blamed them for the successes of the Ottomans. Furthermore, individual moral and other shortcomings could be "Turkified".45 The religious-theological discourse of alterity that turned Muslims into the antithesis of European Christianity – or, more accurately, of one's own denominational group – created new images of the self that helped to build and strengthen identity. The image of "the Turk" as the enemy became an integral component of the europäische Abgrenzungsidentität ("European identity of delimitation").46

Thus, Luther was also able to use the "dread of the Turks" to highlight and better define his own teachings.47 In various writings and sermons, Luther repeatedly emphasized the importance of the "Turkish menace" in salvation history. In his apocalyptic view, the Turks were the last enemies of God. But he also saw them as the scourge by which God punished the Christians for their sins. Though Luther was initially of the opinion that any resistance to this instrument of God was futile and that God's wrath could only be appeased by inner repentance, prayer and penance, and by overcoming the internal divisions among Christians, he later developed a theory of defensive war against the Turks.48 In his treatise Vom Krieg wider die Türken [On War Against the Turks] of 1529, however, he also rejected the papal crusading ideology since in his opinion only the secular authorities were permitted to wage war and then only for defensive purposes. In addition, Luther underlined the insurmountable theological differences between Islam and Christianity. Asserting that violence was an inherent characteristic of their religion, Luther stated that Turkish rule lacked any legitimacy. His criticism of polygamy, as permitted in Islamic law, aimed at denouncing the social order of Muslims as unlawful on the family level. In Luther's view, "gehen den Türken also die wahre Religion, die wahre Obrigkeit sowie der wahre Hausstand und damit die tragenden Strukturen der Gesellschaft ab."49

of 1529, however, he also rejected the papal crusading ideology since in his opinion only the secular authorities were permitted to wage war and then only for defensive purposes. In addition, Luther underlined the insurmountable theological differences between Islam and Christianity. Asserting that violence was an inherent characteristic of their religion, Luther stated that Turkish rule lacked any legitimacy. His criticism of polygamy, as permitted in Islamic law, aimed at denouncing the social order of Muslims as unlawful on the family level. In Luther's view, "gehen den Türken also die wahre Religion, die wahre Obrigkeit sowie der wahre Hausstand und damit die tragenden Strukturen der Gesellschaft ab."49

Travel accounts and ethnographic treatises of the 16th century added other aspects to the discourse of alterity on Muslims and Turks and introduced important elements for its further development. Travellers did not so much concentrate on the "Turkish menace" in their publications, rather they wrote about cultural and social phenomena they observed in the Ottoman Empire, focusing naturally on those that differed from the ones at home. "Die Türken erscheinen hier nicht als die heilsgeschichtlichen Erbfeinde, sondern als Objekte des enthnographischen Blicks."50 Although accounts of the manners and customs of Muslims were often employed to confirm and support the circumstances and norms at home,51 the empirical information provided by travelogues expanded European knowledge of Islam and became part of a new ethnographic discourse that dealt with Islam in a more detached and factual manner than religious-theological treatises. Empirical insights and the use of scientific categories of description for Islam laid the foundation for a new understanding of religion, which made it possible to regard Islam as a religion equal to Christianity.52

On occasion, authors of 16th-century travel accounts reported positive aspects of the state and society of the Ottoman Empire that they had observed. Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq (1522–1592), who was in the service of a Habsburg envoy to Istanbul from 1554 to 1562, described the Ottoman Empire as a meritocracy and he contrasted it positively with the privileges of the nobility predominating in his home country . He also had a positive opinion of the order and regularity of the political and social organization of the empire, which he regarded as being exemplary.53 This shows that the situation in the Ottoman Empire could also be used as a foil for criticising one's own society. However, stereotypes persisted in many travel accounts. Thus, the Sultan's rule was often described as a tyranny under which the Christian subjects, in particular, suffered. Furthermore, new stereotypes were also being created, such as the image of the all-powerful sultan and the invincible state system.

. He also had a positive opinion of the order and regularity of the political and social organization of the empire, which he regarded as being exemplary.53 This shows that the situation in the Ottoman Empire could also be used as a foil for criticising one's own society. However, stereotypes persisted in many travel accounts. Thus, the Sultan's rule was often described as a tyranny under which the Christian subjects, in particular, suffered. Furthermore, new stereotypes were also being created, such as the image of the all-powerful sultan and the invincible state system.

The image of Islam in the age of the Renaissance and the Reformation was characterized by the discourse of the "Turkish menace". It carried, on one hand, conventional religious topoi (Islam as heresy, as the forces of the Antichrist) and, on the other, ethnic stereotypes (the Turks as barbarians) that were part of a long tradition. The Turks always appeared as the essential "other" and as an existential threat to the "self". The image of the Turk as the enemy became an integral component of the world-view of many Europeans. It was disseminated and strengthened by sermons, pamphlets and other types of literature. While Islam and "the Turks" were considered the antithesis of the "self", they were not entirely outside the world of central and western Europeans. Rather, they were part of their world and could be used in propaganda against opposing confessions or to mirror the faults of one's own society. However, the image of the Muslim "other" mostly served to strengthen one's own identity, be it as a Protestant or a Catholic Christian, or as a "civilized European".

The Image of Islam in the Discourses of the Enlightenment

The European image of the Turks and Islam that had crystallized in the 15th and 16th centuries was quite stable. Towards the end of the 17th century, however, a change became evident.54 The preconditions for this change were, on the one hand, a more detached view and new knowledge disseminated by travelogues and, on the other, the changed military and political situation. The defeats of the Ottomans in the second siege of Vienna (1683) and in the "Great Turkish War" (1683–1699) against the Holy League55 marked the end of Ottoman expansive power in central Europe. "Triumphalism" and "mockery of the Turks" replaced the "dread of the Turks" and the discourse of the "Turkish menace" in the Habsburg countries, but simultaneously affirmed the negative image of the Turks.56 While the perception of the Turks as enemies endured for a long time among the less-educated lower classes, a change to a more positive image gradually took place among the elite and the educated.

and in the "Great Turkish War" (1683–1699) against the Holy League55 marked the end of Ottoman expansive power in central Europe. "Triumphalism" and "mockery of the Turks" replaced the "dread of the Turks" and the discourse of the "Turkish menace" in the Habsburg countries, but simultaneously affirmed the negative image of the Turks.56 While the perception of the Turks as enemies endured for a long time among the less-educated lower classes, a change to a more positive image gradually took place among the elite and the educated.

This transformation initially occurred in western Europe.57 In the court society of Louis XIV (1638–1715) "turqueries" were becoming fashionable, gallant Moors and Muslim heroes appeared in French theatre and literature, while Muslim Spain (Al-Andalus) acquired positive connotations

.58 Turks, Moors and everything Oriental were considered exotic in elite culture. This enthusiasm for the exotic Orient started in France with an Ottoman embassy to Paris in 1669 and a Moroccan embassy which arrived in the French capital a little later. In literature, the Oriental fashion probably began with Jean Racine's (1639–1699) tragedy Bajazet (1672). It reached a climax shortly after 1700, when Antoine Galland's (1646–1715) translation of the One Thousand and One Nights (1704–1711)

.58 Turks, Moors and everything Oriental were considered exotic in elite culture. This enthusiasm for the exotic Orient started in France with an Ottoman embassy to Paris in 1669 and a Moroccan embassy which arrived in the French capital a little later. In literature, the Oriental fashion probably began with Jean Racine's (1639–1699) tragedy Bajazet (1672). It reached a climax shortly after 1700, when Antoine Galland's (1646–1715) translation of the One Thousand and One Nights (1704–1711) provided a standard for the exotic image of the Orient.59 At the same time, travellers sought to correct conventional stereotypes, among them Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762) who tried to rectify the image of Ottoman women distorted by harem clichés.60

provided a standard for the exotic image of the Orient.59 At the same time, travellers sought to correct conventional stereotypes, among them Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762) who tried to rectify the image of Ottoman women distorted by harem clichés.60

With the early Enlightenment, a more objective and positive view of Islam as a religion became established in scholarship.61 Richard Simon (1638–1712) rejected the description of Middle Eastern religions as heresies and recognized Islam as a variant of the same monotheistic belief.62 The Bibliothèque orientale by Barthélemy d'Herbelot (1625–1695), which was completed in 1697 by Antoine Galland, was the first encyclopaedia of the Middle East that did not construct an opposition between Islam and Christianity, Orient and Occident, and that did not make generalized statements.63 In 1730, the first objective biography of the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) was penned by Henri de Boulainvillier (1658–1722).64 Many intellectuals of the age of Enlightenment perceived Islam as a tolerant religion or underlined its rationality and simplicity, contrasting these positively with Christian dogmas, which were so difficult to grasp on a rational level. The historization of Islam and the varied interest shown by representatives of the Enlightenment65 also had downsides, however. Philosophers of the Enlightenment often used Islam and its prophet as an argument in their critique of ecclesiastical authorities and their teachings. In the process, they often reused old stereotypes66 or developed new ones. Thus, Voltaire (1694–1778) in his general critique of religion portrayed the prophet as an impostor and a fanatic, and as such used him as a mirror of that which he criticized in the Catholic Church. Denis Diderot (1713–1784) and others drew a link between Islam and fanaticism, or used accusations against Islam as indirect attacks against the Catholic Church.67

by Barthélemy d'Herbelot (1625–1695), which was completed in 1697 by Antoine Galland, was the first encyclopaedia of the Middle East that did not construct an opposition between Islam and Christianity, Orient and Occident, and that did not make generalized statements.63 In 1730, the first objective biography of the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) was penned by Henri de Boulainvillier (1658–1722).64 Many intellectuals of the age of Enlightenment perceived Islam as a tolerant religion or underlined its rationality and simplicity, contrasting these positively with Christian dogmas, which were so difficult to grasp on a rational level. The historization of Islam and the varied interest shown by representatives of the Enlightenment65 also had downsides, however. Philosophers of the Enlightenment often used Islam and its prophet as an argument in their critique of ecclesiastical authorities and their teachings. In the process, they often reused old stereotypes66 or developed new ones. Thus, Voltaire (1694–1778) in his general critique of religion portrayed the prophet as an impostor and a fanatic, and as such used him as a mirror of that which he criticized in the Catholic Church. Denis Diderot (1713–1784) and others drew a link between Islam and fanaticism, or used accusations against Islam as indirect attacks against the Catholic Church.67

"Fanaticism" was a new term that entered the discourse on Islam via the Enlightenment's critique of religion.68 It took the place of older judgmental terms such as falseness, heresy, sham and lawlessness, with which Islam and Muslims had previously been associated, that is, those stereotypes that Boulainvilliers had tried to refute with his biography of Muḥammad.69 He and other philosophers of the Enlightenment, such as Voltaire and Simon Ockley (1678–1720), appreciated the virtues of the Arabs and Muslims of the Middle Ages and praised their contributions to philosophy, medicine and other sciences.70 But, at the same time, they bemoaned the devastation that Muslim fanaticism had supposedly caused in the Middle East. This perspective on the Muslim past was accentuated by the perceived political, military and economic decline of the Ottoman Empire since its defeat at the gates of Vienna. The contrast between a glorious past and a grim present constructed a new alterity. It could now be argued that Muslims were backward because they were not participating in the progress that Europe was achieving via the Enlightenment. Islam was often seen as the reason for the allegedly desolate condition of Middle Eastern countries because it was regarded as being hostile to science and preventing Enlightenment and progress.71 This created the context for a new image, that of the fanatical, ignorant, obscurantist and backward Muslim as the opposite of the enlightened and progressive European.

Apart from fanaticism and hostility to the sciences, another important prejudice was established by the Enlightenment, namely that of despotism. The use of the terms "despotism" and "Oriental despotism" to characterize political and social systems in Asia, especially in the Middle East, became customary in the mid-18th century.72 However, it was already noticeable towards the end of the 16th century that the peculiarities of the Ottoman Empire's socio-political structure that had formerly been judged in a positive or neutral way were now regarded negatively. Until about 1575, reports by Venetian diplomats presented the Ottoman Empire as a legitimate, even normal system of governance. They spoke with a certain fascination and admiration of the Sultan's realm, though this fascination was always paired with aversion. The centralized Ottoman state and the Sultan were considered to be powerful; the submissiveness and obedience of the people were praised as exemplary, and it was recognized that the (religious) law sufficiently prevented abuse of power.73 Before 1575, only isolated comments on tyranny in the Ottoman Empire can be found in the Venetian diplomatic reports. This, however, changed radically after 1575, as Venetian envoys more strongly emphasized the otherness of the political and social organization of the Ottomans and labelled it with derogative adjectives. Thus, the Ottomans were characterized as the opposite of the "self" and their empire as "the largest tyranny in history".74 This transformation of the Venetian perception is primarily linked to the new political image that the Venetian elites had of themselves: they regarded themselves as members of a free republic. The European debates about legitimate forms of government also played an important role in this change of the image of the Ottoman Empire.75

Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689–1755)[ ] created in his work De l'esprit des lois (1747) a comprehensive theory and ideal type of despotism. Montesquieu characterized despotism not only as a form of political rule but also as a form of society, since despotic rule could pervade the entire community. In Montesquieu's ideal type, societies characterized by despotism have the following characteristics: the ruler (despot) stands above the law and his will is the law; there are no forces such as a nobility or a hereditary aristocracy that limit his rule; therefore, the despot can rule by means of a completely dependent administrative elite; the latter, as well as the subjects, have a slave mentality; in the relationship between the ruler and the subjects, as well as among the subjects, fear reigns, so that despotism also predominates in the household and family; furthermore, in a community characterized by despotism, there is no private ownership of land (everything belongs to the despot); and, finally, despotic rule results in the unbridled exploitation of nature.76 According to Montesquieu, order in societies characterized by despotism is maintained by fear and blind obedience; he saw no possibility for political change.77 He also presented despotism as the form of government characteristic of Asia, explaining this with the vastness of the land that favoured large empires and the hot climate prevalent in Asia. He held the view (as Aristotle [384–322 BC] did long before him) that hot climates soften people and thereby turn them into slaves, while people in moderate climatic zones (i.e. Europe) tend towards bravery and, consequently, were in a position to maintain and defend their freedom.78 Therefore, in the great expanses and heat of Asia, the despotic form of government prevailed, while in Europe the moderate regimes of monarchy and republic were the rule. According to Montesquieu, therefore, despotism emerges in Asia as if by a law of nature. By situating despotism in Asia, and especially in the Muslim empires of the Ottomans, Safavids and Moguls, to which Montesquieu continuously refers in his analysis,79 he – and others who elaborated on his theories – constructed an unbridgeable difference between East and West, between Muslim and European societies. Thus, the Oriental society with its despotic style of governance, its slave mentality and its all-pervading fear was constructed as the antithesis of the free European society in which law reigns, and virtue (in the republics) or honour (in the monarchies) determine political culture.

] created in his work De l'esprit des lois (1747) a comprehensive theory and ideal type of despotism. Montesquieu characterized despotism not only as a form of political rule but also as a form of society, since despotic rule could pervade the entire community. In Montesquieu's ideal type, societies characterized by despotism have the following characteristics: the ruler (despot) stands above the law and his will is the law; there are no forces such as a nobility or a hereditary aristocracy that limit his rule; therefore, the despot can rule by means of a completely dependent administrative elite; the latter, as well as the subjects, have a slave mentality; in the relationship between the ruler and the subjects, as well as among the subjects, fear reigns, so that despotism also predominates in the household and family; furthermore, in a community characterized by despotism, there is no private ownership of land (everything belongs to the despot); and, finally, despotic rule results in the unbridled exploitation of nature.76 According to Montesquieu, order in societies characterized by despotism is maintained by fear and blind obedience; he saw no possibility for political change.77 He also presented despotism as the form of government characteristic of Asia, explaining this with the vastness of the land that favoured large empires and the hot climate prevalent in Asia. He held the view (as Aristotle [384–322 BC] did long before him) that hot climates soften people and thereby turn them into slaves, while people in moderate climatic zones (i.e. Europe) tend towards bravery and, consequently, were in a position to maintain and defend their freedom.78 Therefore, in the great expanses and heat of Asia, the despotic form of government prevailed, while in Europe the moderate regimes of monarchy and republic were the rule. According to Montesquieu, therefore, despotism emerges in Asia as if by a law of nature. By situating despotism in Asia, and especially in the Muslim empires of the Ottomans, Safavids and Moguls, to which Montesquieu continuously refers in his analysis,79 he – and others who elaborated on his theories – constructed an unbridgeable difference between East and West, between Muslim and European societies. Thus, the Oriental society with its despotic style of governance, its slave mentality and its all-pervading fear was constructed as the antithesis of the free European society in which law reigns, and virtue (in the republics) or honour (in the monarchies) determine political culture.

Montesquieu used late-17th-century European travel accounts as sources for his analysis of Asian political systems.80 His assessment of the Ottoman Empire was based mainly on Sir Paul Rycaut's (1626–1700) Present State of the Ottoman Empire (1668).81 Rycaut, who was the English consul in Smyrna (İzmir) from 1667 to 1678 and whose book achieved "canonical" status in the 18th century, included arbitrary and brutal rule, the absence of a nobility or an aristocracy, severe punishment, and blind obedience of the subjects among the Ottoman maxims of state. He considered tyrannical rule to be the source of the empire's might and greatness.82 Montesquieu took his information on the Mogul Empire in India from the writings of François Berniers (1620–1688), who compared the situation there with that in France and painted a picture of two different cultures, of which one – Muslim and Oriental – was in decline due to a despotic regime that promoted exploitation and corruption, while the other – French – was prospering due to a hereditary nobility, private property rights, economically independent towns and the protection of all estates by the law.83 Montesquieu's assessment of the situation in Persia was based on the writings of Jean Chardin (1643–1713).84 However, in the process of formulating his theory, Montesquieu ignored the many distinctions Chardin drew regarding the Safavid Empire, especially Chardin's assertions that there was indeed private landownership in Persia, and that the despotism prevalent at court did not affect the masses of the subjects, who were not the king's slaves.85 Montesquieu used his sources very selectively; he used information that supported his theory, but omitted what contradicted it,86 and thereby condensed his theory into an asymmetrical typology of East and West.87 While Montesquieu's primary motivation was not hostility to Islam, he nevertheless disseminated stereotypes of Islam and drew a connection between Islam and despotism: according to Montesquieu, Islam favoured arbitrary and cruel punishment and made people worship their ruler, and Muslims tended towards laziness and fatalism because of their belief in predestination.88 He thus created a deterministic dichotomy and accepted as self-evident the concept of a vast difference between Europe and the Orient. In this way, despotism became "the axis around which the image of the Other would revolve".89

Montesquieu's political theory must in the first place be understood as a critique of absolutist tendencies in France. His descriptions of despotism, which appear "like a caricature of the worst moments of Iranian or Turkish history"90, formed an image of terror that was intended to show the French what unrestrained royal rule could lead to. Here, the polyvalence of debates conducted in the age of Enlightenment is evident. The discussion about despotism could, on the one hand, be used to criticize developments and conditions in Europe and, on the other hand, it offered an interpretative framework for the situation in Asian societies. This applies in a similar manner to the topoi of fanaticism and hostility to the sciences. They not only served the analysis of alleged conditions in Muslim societies but could also be used at home in the battle against the power of the Church.

Montesquieu's theory of despotism was by no means undisputed. Voltaire criticized the climatic determinism on which it was constructed and drew attention to the untenability of many of its generalizations.91 Montesquieu's assertions did not withstand the test of empiricism either. Abraham-Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron (1731–1805) and Charles William Boughton Rouse (1747–1821), who disproved Montesquieu's generalizations point by point – the former for the Ottoman Empire, Persia and India, and the latter for Bengal – were, however, not able to overcome the prevailing acceptance of the thesis of Oriental despotism.92 The same applies to the British ambassador in Istanbul, Sir James Porter (1710–1786), who attempted to prove that the Ottoman Empire was a limited monarchy in which scholars of law and religion ('ulamā') scrutinized the ruler and restricted his power.93

Montesquieu's theory could be used to denigrate the non-European world as the seedbed of despotism. As a consequence, many travel writers sought evidence in the Middle East for their preconceived opinions of Oriental despotism and for Montesquieu's thesis – and they found it. François de Tott (1733–1793) encountered despotism everywhere in the Ottoman Empire because he believed it to be a fundamental characteristic of Ottoman society and that despotism and slave mentality, which he thought was rooted in the Muslim belief of predestination, were character traits of the Turks.94 Lesser known authors such as William Eton also sought and found despotism in the Ottoman Empire. For Eton, the Sultan's despotism was closely related to the people's "superstition" and "prejudices", the foundations of which he identified in Islam, which he considered to be "absurd". He presented the despotism of the Ottomans as the antithesis of England's form of governance, which was embedded in laws and rules.95

Very often, a connection was also drawn between polygamy, which was permitted by Islamic law, and despotism; indeed, Montesquieu had described the harem as despotism en miniature.96 According to Arnold Hermann Ludwig Heeren (1760–1842), despotism was built on polygamy. Polygamy led to "family despotism" because it made the woman the slave of the man, who – as a result – became a despot. Despotism, therefore, came from below, from the family; and not from above, from the ruler. Thus, it was impossible for domestic virtues to develop in Muslim societies and, in consequence, there could be no civic society either.97 A much older set of arguments re-emerged here. Luther had described the social order of Muslims as illegitimate because of polygamy. Polygamy, the lack of freedom for women and their isolation in the harem, were generally considered "deficiencies of Islam" to which the morally superior monogamy in Europe was juxtaposed.98

Towards the end of the 18th century, the theory of despotism was used to deny the legitimacy of Middle Eastern regimes. Constantin-François Chassebœuf de Volney (1757–1820) is one example. According to Volney, the Ottoman Empire was an illegitimate state that exploited its subjects.99 He held that the entire population was exposed to the arbitrariness and predatory despotism of the military elites and that despotism and exploitation had resulted in the countries of the Middle East being entirely desolate, a topos that not only circulated in the age of Enlightenment but already in travel accounts of the 16th century. Volney drew a close connection between despotism and Islam, since both "cast humans into the chains of ignorance".100 To him, Islam was an obstacle to progress, the Koran predominantly a "tissue of vague phrases, empty of meaning", a "collection of puerile stories, of ridiculous fables", in which the spirit of fanaticism was evident and which in turn produced the "most absolute of despotism".101 Unlike Montesquieu, Volney did not consider despotism to be an irreversible phenomenon caused by the Asian climate, but a political phenomenon which was, therefore, subject to change. Based on the concept of despotism, Volney constructed a dichotomy between progress and secular rationality in Europe, on the one hand, and backwardness, ignorance and religious and political irrationality in the Middle East, on the other. His argumentation was heavily tinged by a discourse of superiority. By demonising despotism, he denied legitimacy to Ottoman rule. This discourse of superiority provided justification for prospective "well-intentioned" European interventions in the Middle East, since the introduction of European sciences was thought to be necessary in order to fight despotism and remedy the desolate conditions.102

In this way, the 18th century provided a new discourse of alterity. Islam and societies influenced by Islam were no longer defined as the "other" in terms of religious criteria, but in terms of secular criteria. The old discourse of alterity that had arisen from a feeling of being militarily threatened and inferior gave way to a new discourse of superiority. This discourse was based on a set of stereotypes that consisted of the cultural prejudices of despotism, fanaticism, hostility to the sciences, and backwardness, which were deployed to draw a distinction between the Muslim Orient and Europe. During the 19th century, this discourse became even more prevalent with the thesis that Islam and modernity, Islam and Europe were incompatible.103 In the context of the development of European hegemony in the late-18th century, Europeans began to regard "the Orient" and "the Occident" as two irreconcilable and contrary civilizations.104 They did so despite the fact that, up to the mid-18th century, there was no consensus whatsoever on where the geographical borders of Europe should be drawn, let alone the cultural ones. However, the Ottoman Empire was increasingly being excluded from Europe. The idea of Europe as an exclusive community of values was born; it was based on the assumption that, since the time of the ancient Greeks, an essential cultural continuity and coherence had existed through time and space, an assumption that implied that influences from the "outside" were negated or ignored.105 In this way, Europeans always defined themselves in relation to others, in contrast to the non-European world. Europe became the home of freedom, law, rationality, science, progress, intellectual curiosity, entrepreneurship and invention, all core values of Europeans that were traced back to the ancient Greeks, and that set them apart from the Orient, from Islam.

The Image of Islam in Imperialism and Orientalism

In the summer of 1798, French troops under Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) invaded Egypt. Although the occupation barely lasted three years, it was a watershed in the European perception of the Middle East and Islam. For the first time since the Crusades, Europeans seized power in one of the Muslim heartlands. The Enlightenment discourse resonated in the rhetoric used by Revolutionary France to justify its colonial enterprise. The French claimed to be liberating Egypt from the yoke of Mamluk and Ottoman "despots" and to be carrying the light of Enlightenment and Freedom to the Orient.106 Volney's interpretation of the conditions in Egypt and the Levant gained direct political relevance because the leaders of the Armée d'Egypte understood his Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte of 1787 as a kind of "guidebook" for the expedition.107

of 1787 as a kind of "guidebook" for the expedition.107

At the same time, the paradigm of the superiority of European civilization became dominant. Academics constructed the master narrative of the rise of Europe, and Europe was soon considered the universally valid model. The Islamic Middle East and the Ottoman Empire were excluded from this narrative. In the 1780s, Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) described the Ottomans as strangers who did not belong to Europe because they were not only unwilling, but also incapable, of adapting to European culture.108 Around three and a half decades later, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) in his Vorlesungen über die Philosophie der Weltgeschichte [Lectures on the Philosophy of World History] (1822–1823) described world history as a history of reason that realizes itself in time, with the course of history moving from East to West. Associating the Orient with stagnation and immobility, he considered the history of Islam relevant only in so far as Muslims had inspired the European peoples with ideas and principles when Muslim civilization had been at its height a long time ago. But only through their acquisition by Europeans could these ideas and principles be developed and gain potency. Thus, the remainder of Islamic history appears as decline and Islam is portrayed as irrelevant to modern history.109 This marginalization and removal of Islamic history from world history, which was increasingly seen as a European history, was also reflected in the growing specialization of the humanities. The global field of reference that had prevailed in Enlightenment scholarship was divided up, and regionally defined sub-disciplines for the studies of the history, culture and religion of societies in Asia were established.110

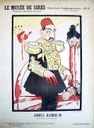

On the political and economic level, the first decades of the 19th century were characterized by the consolidation of European hegemony over non-European societies and the strengthening of the colonial empires, especially the British Empire. At the margin of Europe, the "Oriental question" became increasingly important, that is, the question of how much of the Ottoman Empire – which now became known as the "Sick man of Europe" – was to be preserved and which European powers were to have influence (and how much influence) in the lands of the Sultans without jeopardizing the European balance of power. During the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830), which triggered a wave of anti-Ottoman propaganda and enthusiasm for the cause of the Greeks (Philhellenism) in Europe, the image of the Turks deteriorated. As had already occurred in the 15th and 16th centuries and reflecting also the exclusion of the Ottomans from European history in academic discourse, the Ottomans were depicted as un-European barbarians.111 The situation of Christian minorities which – under the influence of nationalist ideas – strove for self-determination offered the European powers many opportunities for intervention. Uprisings and ethnic conflicts in the last quarter of the century (Bosnia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, East Anatolia) and the acts of violence committed there – by all parties – played their part in further darkening the image of the Ottomans. The European public merely perceived the violence of the Muslim/Ottoman side. Sultan Abdülhamid II (1842–1918) became the "Red Sultan" whose hands were dripping with the blood of his victims ; the Ottomans became the "Ugly Turks".112 Furthermore, during the last two decades of the 19th century and the first two of the 20th, almost every Muslim country was subjected to European colonial rule.113 Those states that were able to maintain their political independence (the Ottoman Empire, Persia, Afghanistan) were frequently in a state of semi-colonial subordination to one or several European powers.

; the Ottomans became the "Ugly Turks".112 Furthermore, during the last two decades of the 19th century and the first two of the 20th, almost every Muslim country was subjected to European colonial rule.113 Those states that were able to maintain their political independence (the Ottoman Empire, Persia, Afghanistan) were frequently in a state of semi-colonial subordination to one or several European powers.

In the 19th century, numerous stereotypes circulated that to a degree continue to shape the image of Islam and Muslims to this day. It was alleged that Islam does not know a separation of state and religion, that Muslims cannot conceive of a secular social and state order, that knowledge stagnates in Muslim societies and can only be developed through the adoption of European ideas and standards (Europeanization/Westernization is required), that Islam oppresses women and that Islam is anti-modern. Particularly widespread was the stereotype that Islam is the obstacle to modernization, enlightenment and progress in the Muslim Orient, and that Islam is the reason why it was inferior in political, military, economic and, ultimately, cultural terms.

These negative perceptions of the Orient, however, stood in contrast to positive ones. There was, for example, the idea of a poetic Orient as the unspoiled source of mysticism and spirituality for which many Europeans longed.114 In the image of the Orient, therefore, positive stereotypes, clichés and topoi competed with negative ones; it was an image that fluctuated between idealization and demonization. The Orient became the surface on which desires and fears were simultaneously projected. It is probably this Janus-headed quality that best describes the image of the Orient throughout the entire 19th century.115 When Europeans travelled to the Middle East in search of the poetic Orient (one can speak of tourism from the second quarter of the 19th century),116 the encounter with the real Orient resulted time and again in disappointments. No fairytale palaces could be found. There weren't even any "true" Oriental cafés in Cairo, as Gérard de Nerval (1808–1855) bemoaned. Oriental cafés that lived up to his ideas of the exotic and opulent could only be found in Paris!117 Another example is the French journalist and writer Louise Colet (1810–1876), who stayed at the court of the Khedive of Egypt in 1869 during the festivities for the opening of the Suez Canal. She was disappointed beyond measure that she was offered theatre and opera performances alla franca there. The Orient she would have expected looked quite different. She longed for sabre-wearing Orientals in flowing robes, caftans, fur and slippers who sat on Persian rugs and richly embroidered pillows and smoked pipes while being entertained by Nubian singers and dancers under "Babylonian illuminations".118

This disillusionment promoted the use of the Orient as a surface on which to project everything negative, and it was easy to hold Islam responsible for the negative features of the Orient.119 Conventional images of "the enemy" were revived. As early as the 1820s, the image of the Orient in German popular literature was dominated by negative stereotypes containing partially religious connotations and which postulated the moral superiority of Christianity and Europe. These stereotypes included cruelty and despotism, religious militancy and fanaticism, idleness and disorder, lustfulness and sensuality (embodied by the harem and polygamy)

religious militancy and fanaticism, idleness and disorder, lustfulness and sensuality (embodied by the harem and polygamy) .120 Stereotypical images of this type served to stabilize European identity and culture – by showing how different and superior European culture was.121

.120 Stereotypical images of this type served to stabilize European identity and culture – by showing how different and superior European culture was.121

The European ideas of Islam and of Muslims were characterized in the 19th century by a distinctive essentialism. An eternal and immutable nature was ascribed to Islam and the Orient, an essence that distinguished them fundamentally from Europe. To an even greater degree than in Volney's writings, academic knowledge was used in the age of European Imperialism to legitimize European rule over Muslim societies. In the late-19th and early-20th centuries, fantastical racist theories were added to the stereotypes of Islam that harked back to the age of Enlightenment (fanaticism, hostility to science, despotism, stagnation and backwardness), theories which were also used to prove the superiority of Europe. This discourse of alterity regarding Islam was repeated and defended by academic, literary and political authorities.122 Since the publication of Edward W. Said's (1935–2003) book Orientalism in 1978,123 this line of thought has commonly been called "Orientalism". In this widely received and much discussed polemic, Said described British and French Oriental studies of the 19th century as having established a hegemonic discourse on the Orient and thereby supported western rule in the Middle East.124 These 19th-century Orientalist structures of thought will be illustrated by the following two examples.

Ernest Renan (1823–1892) was a renowned professor, philologist and scholar of religion, who can be considered one of the outstanding French intellectuals of his time. Renan's views of Islam can be found in his L'islamisme et la science, a paper he read at the Sorbonne in 1883 and which reflects ideas that were commonly held in Europe.125 For Renan, Islam was essentially hostile to the sciences. He considered "the Muslim" incapable of learning and of thinking for himself. Rather, the Muslim is seen as fanatical, not accepting new ideas and despising other religions as well as the sciences and the teachings that constitute the "European spirit".126 In his lecture, Renan posed the question as to what contributions the Arabic-Islamic civilization had made to the sciences and philosophy. He arrived at the conclusion that it at best contributed something to the knowledge of humanity only between the late-8th and the 12th centuries, and that this contribution did not come about because of Islam, but in spite of Islam and in opposition to Islam. Furthermore, the contributed knowledge was neither Arabic nor Muslim. Firstly, he regarded all knowledge that the Muslims had at that time to be an adaptation of Greek and Persian knowledge, rather than created by themselves. Secondly, the scientists and philosophers of that time (with one exception) were not Arabs, but Persians, Central Asians or Spaniards. Thirdly, these scholars were not Muslims, but Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians and others, or, if they were Muslims, they had "internally rebelled against their religion".127 Indeed, Renan continued, Islam and Muslims had always fought rational thought and had finally "suffocated" science and philosophy in the 13th century.128 It was at that point in history, according to Renan, as scientific curiosity was in decline in the Islamic world, which had come under the rule of a "Turkish race" or "Tartaric and Berber race" which was averse to all science, that the Greek knowledge transmitted in Arabic was adopted by the Europeans.129 What followed in the Middle East and North Africa was stagnation, religious intolerance and suppression – decline.

Renan's image of Islam stands in the tradition of the Enlightenment, but also deviates from it. As with the representatives of the Enlightenment, Renan's critique of Islam is part of a general critique of religion that also accuses the Catholic Church of animosity to rational knowledge.130 The philosophers of the Enlightenment, however, while assessing the Islam of their times as fanatical, backward and hostile to science, were simultaneously able to appreciate the works of medieval Arabic and Islamic scholars. By contrast, Renan is almost incapable of this appreciation.131

In addition, racist ideas entered Renan's argument. When the Muslim scholar Ǧamāladdīn al-Afġānī (1838/39–1897) reacted to Renan's criticism and answered him that Muslims had to struggle with the same problems as Christians on their road to a free, rational interpretation of the world, that is, with rigid dogmas and religious hierarchies that must be overcome, Renan answered in racist categories:

Sheikh Ǧamāladdīn is an Afghan who has rid himself completely of the prejudices of Islam. He belongs to those energetic races of Upper Iran in the proximity of India, in which under the superficial garb of official Islam the Arian spirit is still strongly alive. He is the best proof of the great axiom, which we have so often proclaimed, that religions only count as much as the races that profess them.132

As a philologist, Renan was of the opinion that the "spirit" of a people can be deduced from its language and texts and he defended the concept of a hierarchy of peoples, languages and civilizations. The "Semitic spirit" had produced monotheism, but everything else was a creation of the "Arian spirit".133 Since Arabic was a Semitic language, the Arabic-Islamic civilization was below that of the "Arian" Greeks, Persians and Europeans. Although Renan was convinced that he himself and Europeans in general were superior to Muslims, his image of Islam also appears to have been shaped by fear. But he believed that scientific and technological progress could banish the danger: "If Omar [the second Caliph], if Genghis Khan had come up against a good artillery, they would not have been able to cross the boundaries of their deserts".134 Renan's concepts did not go undisputed,135 but comparable views of European superiority over Muslims were popular in the 19th century.136

Evelyn Baring, the First Earl of Cromer (1841–1917)[ ] is an example of a political figure who supported and contributed to the European discourse on Islam. Cromer held office from 1883 to 1907 as the British Consul-General in Cairo and "advised" in this capacity the Khedive of Egypt, whose country was occupied by Britain in 1882. In fact, Cromer governed the country or, rather, governed the government of Egypt.137 Despite his decades of activity in Egypt, Cromer did not deign to learn Arabic.138 Nevertheless, he believed he knew precisely what made the essence of an Egyptian or an Oriental. "The Oriental"/"the Egyptian" was to him in every way the complete opposite of "the European"/"the Englishman": "… the Oriental generally acts, speaks, and thinks in a manner exactly opposite to the European."139 In contrast to the European, he considered the Oriental to be entirely irrational, a perception that was widely accepted at the time:140

] is an example of a political figure who supported and contributed to the European discourse on Islam. Cromer held office from 1883 to 1907 as the British Consul-General in Cairo and "advised" in this capacity the Khedive of Egypt, whose country was occupied by Britain in 1882. In fact, Cromer governed the country or, rather, governed the government of Egypt.137 Despite his decades of activity in Egypt, Cromer did not deign to learn Arabic.138 Nevertheless, he believed he knew precisely what made the essence of an Egyptian or an Oriental. "The Oriental"/"the Egyptian" was to him in every way the complete opposite of "the European"/"the Englishman": "… the Oriental generally acts, speaks, and thinks in a manner exactly opposite to the European."139 In contrast to the European, he considered the Oriental to be entirely irrational, a perception that was widely accepted at the time:140

The European is a close reasoner; … he is a natural logician, albeit he might not have studied logic; he loves symmetry in all things; he is by nature sceptical and requires proof before he can accept the truth of any proposition … The mind of the Oriental, on the other hand, like his picturesque streets, is eminently wanting in symmetry. His reasoning is of the most slipshod description. … The Egyptian is also eminently unsceptical. … [T]he Egyptian will, without inquiry, accept as true the most absurd rumors.141

For Cromer, the differences in thought, customs, religion and political ideas created insurmountable barriers between Egyptians and Englishmen, so that mutual understanding was as good as impossible.142 According to Cromer, these differences were due to race:

Consider the mental and moral attributes, the customs, art, architecture, language, dress, and tastes of the dark-skinned Eastern as compared to the fair-skinned Western. It will be found that on every point they are the poles asunder.143

Apart from race, Cromer identified Islam as the reason why Egyptians were fundamentally different and backward. Cromer writes that "as a social system, it [Islam] is a complete failure".144 The reasons were the following: the subordinate position of women, polygamy and the separation of the spheres of men and women, which had devastating consequences not only for women, but – morally – also for men; the rigidity and irrationality of the religious and legal traditions that permitted no separation of state and religion, obstructed the development of capitalism and brutalized people by issuing severe sentences; slavery, which is immoral but permitted in Islamic law; and, finally, intolerance, which is inherent to the Islamic religion. For Cromer, Islam was not compatible with modern civilization in the European-Christian sense, nor could it be reformed because a reformed Islam would no longer be Islam. In general, Orientals were lethargic and conservative to such a degree that they resisted any innovation.145 Nevertheless, the English – an "imperial race" with "sterling national qualities", driven by selfless Christian morality – had a mission in Egypt: to bring order to chaos, to educate the immature Egyptians, who were not capable of governing themselves, and to elevate them morally and materially to a higher level, and to fight corruption.146 In other words, the English were the doctors of a sick society; their rule over the Egyptians, who were inferior due to race and religion, was not only legitimate, but even necessary.

Cromer's view of Egyptians, Muslims and Orientals exemplifies the close intertwining of Orientalist knowledge and colonial power. The separation of Orient and Occident suggested by Cromer, Renan and other authors of the 19th century established a rigid dichotomy between Islam and Europe that was structured by binary pairs of opposites that always implied European superiority: order vs. chaos, rationality vs. irrationality, progress vs. stagnation, enlightenment vs. ignorance, democracy vs. despotism, human vs. inhuman. In this way, a specific essence was ascribed to Islam, to the Orient that differentiated them from Europe. Geographical, social and historical differences within the Islamic world were ignored. The Orient became an eternal entity; Islam and Muslims were conceived as being immutable in their essence and as being the same everywhere.

Future Perspective

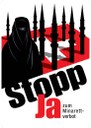

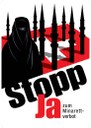

Stereotypes and clichés of Islam have proved to be durable, but have also been subject to change over time and space. However, the process of assuring the "self" by marking Islam off as a danger to the "self" has been a constant that has influenced the construction and shaping of European identity. The discourse of alterity on Islam has always been organized in dichotomies and has implied varying concepts of the greater worth and superiority of one's own culture and society. The idea of a distinctive European identity was based on Christian foundations which were secularized in the age of Enlightenment. The pairs of opposites Christians/pagans and Christians/heretics receded into the background. Another pair of opposites, which was informed by ideas from ancient times, that of Europeans/barbarians, also temporarily lost significance. At the same time, other dichotomies that were connected to the idea of a distinctive European civilization established themselves: rationality/irrationality, rule of law/despotism, progress/stagnation, order/chaos. Finally, in the 19th century, racist ideas were added to justify European superiority. Stereotypes depicting a violent, irrational, fanatical and intolerant Islam, as well as a widespread "Islamophobia"147 are still being politically exploited today. Examples can be named almost at will, be it the "War on Terror" or the Swiss referendum on banning the construction of new minarets . The perception of the Muslim as the "other" of the European, of Islam as the antithesis of Europe and the "West", which is supported by pseudoscientific writings such as Samuel P. Huntington's (1927–2008) Clash of Civilizations, also stands in the way of the integration of people of Muslim faith into the societies of Europe.148

. The perception of the Muslim as the "other" of the European, of Islam as the antithesis of Europe and the "West", which is supported by pseudoscientific writings such as Samuel P. Huntington's (1927–2008) Clash of Civilizations, also stands in the way of the integration of people of Muslim faith into the societies of Europe.148

Felix Konrad

Appendix

Sources

Bernier, François: Travels in the Moghul Empire A.D. 1656–1668, ed. by Vincent A. Smith, London 1914 [Original French edition 1670–1671].

Boulainvilliers, Henri de: La vie de Mahomed, London 1730.

Chardin, Jean: Voyages de Monsieur le chevalier Chardin en Perse et autres lieux de l'Orient, Amsterdam 1711.

Chardin, Jean: Journal de Voyage, London 1686.

Colet, Louise: Les pays lumineux: Voyage en Orient, Paris 1879.

Cromer, Evelyn Baring, Earl of: Modern Egypt, London 1908, vol. 1–2 [Reprint London et al. 2000–2002].

Geldner, Ferdinand (ed.): Der Türkenkalender: "Ein manung der christenheit widder die durcken": Mainz 1454: Das älteste vollständig erhaltene gedruckte Buch: Faksimile und Kommentarband, Wiesbaden 1975.

d'Herbelot, Barthélemy: Bibliothèque orientale ou Dictionnaire universel contenant généralement tout ce qui regarde la connoissance des Peuples de l'Orient, Paris 1697.

Renan, Ernest: L'islamisme et la science: Conférence faite à la Sorbonne, le 29 mars 1883, in: Ernest Renan: Œuvres complètes, ed. by Henriette Psichari, Paris 1947, vol. 1, pp. 944–964.

Ricaut, Paul: The History of the Present State of the Ottoman Empire: Containing the Maxims of the Turkish Polity, the most Material Points of the Mahometan Religion, their Sects and Heresies, their Convents and Religious Votaries: Their Military Discipline, with an Exact Computation of their Forces both by Sea and Land: Illustrated with divers Pieces of Sculpture representing the variety of Habits amongst the Turks: In Three Books, London 1682.

Simon, Richard: Histoire critique de la créance et des coutumes des nations du Levant, Frankfurt 1683.

Volney, Constantin-François de: Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte, pendant les années 1783, 1784 & 1785, vol. 1–2, Paris 1787.

Bibliography

Ágoston, Gábor: Ideologie, Propaganda und politischer Pragmatismus: Die Auseinandersetzungen der osmanischen und habsburgischen Großmächte und die mitteleuropäische Konfrontation, in: Martina Fuchs et al. (eds.): Kaiser Ferdinand I.: Ein mitteleuropäischer Herrscher, Münster 2005, pp. 207–233.

Asad, Talal: Muslims and European Identity: Can Europe Represent Islam?, in: Anthony Pagden (ed.): The Idea of Europe: From Antiquity to the European Union, Washington 2002, pp. 209–227.

Attia, Iman: Die "westliche Kultur" und ihr Anderes: Zur Dekonstruktion von Orientalismus und antimuslimischem Rassismus, Bielefeld 2009.

Badir, Magdy Gabriel: Voltaire et l'Islam, Banbury 1974 (Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 125).