See also the article "The Paris Peace Conference (1919)" in the EHNE.

Introduction

International organisations are institutionalised places of interaction between groups, societies and states, with the goal of agreeing on common norms, values, technical standards and mechanisms for establishing peace. The League of Nations was the first international organisation to unite social, cultural, technical, economic, political and military cooperation under one roof and to claim to represent all regions of the world. By including as many important fields of humanity as possible, the League of Nations became a forum for the promotion of peace and the prevention of war. However, the hopes linked with this promise were first disappointed as a result of the world economic crisis and, finally, shattered by the outbreak of the Second World War. Since then, the League of Nations has been seen as a symbol of the Janus-facedness of the interwar period: In addition to representing a number of innovations in technology, health and social policy that paved the way for the work of the United Nations after 1945 and serving as a participant in the process of globalisation, it embodied European rivalries, the continued existence of colonial structures and the inviolability of national rights of sovereignty. This article discusses this double aspect of the League of Nations. Following the introduction to the significance of the League of Nations and the role of Europe comes a glance at the roots of the new world organisation within the European internationalism of the late 19th century. This is followed by an exposition of the fields of activity, innovations, structural distortions and the legacy of the League of Nations in the United Nations.

The Many Faces of the League of Nations

"The League of Nations, created to preserve peace after a world cataclysm, expired tonight and willed to the United Nations its physical assets in the hope that the new organisation might succeed where the League has failed."1 In view of the catastrophic extent of the Second World War, it was hardly surprising that, in April 1946, a prominent newspaper such as the New York Times had connected the League of Nations with the failure of the global order that had been heralded with such optimism in the 1919 Paris peace treaties 1919. By forging a link of multilateral politics and transnational cooperation in economic, cultural and social questions, the League of Nations served as the central pillar of an architecture of peace that American president Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) [

1919. By forging a link of multilateral politics and transnational cooperation in economic, cultural and social questions, the League of Nations served as the central pillar of an architecture of peace that American president Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) [ ] had presented to the public in his 14-point programme in January 1918.2

] had presented to the public in his 14-point programme in January 1918.2

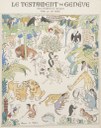

The sobering estimate that the League of Nations had failed Bild Le testament de Genève, as an organisation also had an effect beyond the immediate post-war period. This was combined with the viewpoint that the League of Nations had remained a paper tiger in questions of security policy and had failed to realise its universal claims, since, from the beginning, it had remained a European institution dominated by the great powers France and Great Britain. With its seat in Geneva and two General Secretaries recruited from the British and French administrative systems, Sir Eric Drummond (1876–1951) and Joseph Avenol (1879–1951),3 the European influence remained dominant as the number of member states grew to 61

Bild Le testament de Genève, as an organisation also had an effect beyond the immediate post-war period. This was combined with the viewpoint that the League of Nations had remained a paper tiger in questions of security policy and had failed to realise its universal claims, since, from the beginning, it had remained a European institution dominated by the great powers France and Great Britain. With its seat in Geneva and two General Secretaries recruited from the British and French administrative systems, Sir Eric Drummond (1876–1951) and Joseph Avenol (1879–1951),3 the European influence remained dominant as the number of member states grew to 61 , particularly since the 26 European member states financed approximately 65 percent of the institution’s budget.4 In addition to this, from 1920 onwards, the humanitarian, social and economic committees of the League concentrated on aid measures and reconstruction in Central and Eastern Europe. Only with the declining political importance of the League of Nations in the 1930s did the organisation begin to turn its attention to big social and health projects

, particularly since the 26 European member states financed approximately 65 percent of the institution’s budget.4 In addition to this, from 1920 onwards, the humanitarian, social and economic committees of the League concentrated on aid measures and reconstruction in Central and Eastern Europe. Only with the declining political importance of the League of Nations in the 1930s did the organisation begin to turn its attention to big social and health projects in Asia and Africa.5

in Asia and Africa.5

The same applied to the classical diplomatic disciplines of safeguarding peace, conflict resolution and the regulation of rights of sovereignty, which had been defined by the victorious powers of the First World War as the first task of the League of Nations. With the exception of the Manchurian crisis of 1931 , the Italian-Abyssinian conflict in 1936 and the mandate policy

, the Italian-Abyssinian conflict in 1936 and the mandate policy , which dealt with the trusteeship of the formerly German colonies and Ottoman territories, the emphasis here was, once again, on Europe. The cities placed under the international supervision of the League of Nations, Danzig and Fiume (Rijeka), together with the Saar region, were the legacy of the collapsed European empires. The right to national self-determination applied only to minorities in Central and Eastern Europe, and the cases of successful solution of conflicts in the 1920s resulted primarily from frontier conflicts between European states.6

, which dealt with the trusteeship of the formerly German colonies and Ottoman territories, the emphasis here was, once again, on Europe. The cities placed under the international supervision of the League of Nations, Danzig and Fiume (Rijeka), together with the Saar region, were the legacy of the collapsed European empires. The right to national self-determination applied only to minorities in Central and Eastern Europe, and the cases of successful solution of conflicts in the 1920s resulted primarily from frontier conflicts between European states.6

In retrospect, the League of Nations realised its greatest effect in the sphere of humanitarian and technological cooperation. The General Secretariat in Geneva was provided with departments that supported work on transnational cooperation problems in fields that, before 1914, had already been the object of international cooperation of civil society initiatives.7 This included the Economic and Financial Organisation; the Health Organisation; the Organisation for Communication and Transit; and the International Committee for Intellectual Cooperation. In addition, the Social Section focused on the trafficking of opium and other narcotics, child protection and prostitution in conjunction with the League refugee organisation, with Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930) as its first High Commissioner.8 This "Third League of Nations"9 rediscovered in recent years rendered possible meetings and exchanges of opinion between state representatives, civil society groups and experts in various fields, helping to mould them with its self-created norms of international law.10 Its social, humanitarian, economic and technological activities show the League of Nations today as an innovative experiment that has left its mark on the 20th century in many ways. The view of its supposed failure in the field of power politics has thus been replaced by the picture of "many Leagues of Nations". Civil society groups were able to internationalise their initiatives, which opened a new chapter in the history of transnational cooperation.11

From Pre-War Internationalism to the League of Nations

The First World War proved to be a catalyst for the idea of a post-war order based on principles of collective security and cross-border cooperation. Shortly after the outbreak of war, private organisations were founded in France, Great Britain and the USA that pressed for peace and put forward ideas for shaping the post-war period. The British League of Nations Society, founded in 1915; the Association française pour la Société des Nations of 1918; and the League to Enforce Peace, founded in New York in 1915, acquired several hundred thousand members during the war years, who propagated an international union of states among the general public and the various governments. This idea was not to abolish national sovereignty but to integrate it into a type of federalist order based on international law. Behind this belief laid the hope that political conflicts could be settled once decisions on an international level were matched with the interests of nation states.12 This tradition of liberal internationalism can be traced back to the 1860s. By founding a number of international organisations, its goal was to standardise regulations of communication, railways, the postal service, intellectual property, time zones, weights and measures.13 In a second wave from the 1880s onwards, topics of social policy, hygiene, dealing with international conflicts and, as the Universal Race Congress and the International Council of Women showed, the emancipation of legally disadvantaged groups, all came into the international agenda.14 On the one hand, these organisations documented the gradual development of an international civil society (though restricted to Western bourgeois elites). This demanded active political rights of participation in decisions and acquired influence on national governments by forming a transnational community of interests. On the other hand, prominent representatives of organised pacifism, the international women's movement and advocates of international arbitral jurisdiction made an active contribution to drafting a new peace order. By making a connection between disarmament, the establishment of an international court of law, the regulation of working standards and the prohibition of the opium trade, they prepared the way for the idea of a world organisation and propagated a broad concept of peace.15

Pre-war internationalism was reflected in the charter of the League of Nations. Article 14 provided for the establishment of a Permanent International Court of Justice, whose aim was to settle disputes between the member states. The organisation was launched in 1922 at The Hague, thus fulfilling the promise of the Hague conferences of 1899 and 1907, which provided for the peaceful settlement of international conflicts after failing in 1907.16 The International Labour Organisation (ILO), whose founding was laid down in Article 23 and whose statute was a component of the Versailles Peace Treaty, furthered the approach to an international social policy. This had been drawing attention across frontiers since 1901, with the International Association for the Protection of Labour and the connected International Labour Office in Basel. With the declaration that "universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based on social justice", the founder states of the League of Nations and the ILO reacted not least to the Russian Revolution.17 The intention to act against the trafficking of opium as well as that of women and children, also proclaimed in Article 23, was also not without foundation: The fight against the white slave trade was taken up in the charter on the initiative of the International Council of Women (founded in 1888) and developed into a central field of activity of the Social Section, headed by the British social reformer Dame Rachel Crowdy (1884–1964) [

in 1922 at The Hague, thus fulfilling the promise of the Hague conferences of 1899 and 1907, which provided for the peaceful settlement of international conflicts after failing in 1907.16 The International Labour Organisation (ILO), whose founding was laid down in Article 23 and whose statute was a component of the Versailles Peace Treaty, furthered the approach to an international social policy. This had been drawing attention across frontiers since 1901, with the International Association for the Protection of Labour and the connected International Labour Office in Basel. With the declaration that "universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based on social justice", the founder states of the League of Nations and the ILO reacted not least to the Russian Revolution.17 The intention to act against the trafficking of opium as well as that of women and children, also proclaimed in Article 23, was also not without foundation: The fight against the white slave trade was taken up in the charter on the initiative of the International Council of Women (founded in 1888) and developed into a central field of activity of the Social Section, headed by the British social reformer Dame Rachel Crowdy (1884–1964) [![Rachel Crowdy IMG Dame Rachel Crowdy, a commandant of the VAD [Voluntary Aid Detachment] and her assistant Miss Monica Glazebrook in their office at the Hotel Christol, Boulogne, Schwarz-Weiß-Photographie, 1919, Photographin: Olive Edis; Bildquelle: © IWM (Q 7978), http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194661, IWM Non Commercial Licence, http://www.iwm.org.uk/corporate/privacy-copyright/licence.](./illustrationen/voelkerbund-bilderordner/rachel-crowdy-img/@@images/image/thumb) ].18 Through the fight against opium

].18 Through the fight against opium , the League of Nations took the initiative in a field of social policy that had already established itself in the mid-1870s as a global field of politics under the guidance of civil society pressure groups. This movement became a part of international law with the International Opium Convention of 1912.19 In Article 24 of the charter, the explicit attempt was formulated to dissolve the pre-war internationalism in the League of Nations. This was to succeed by incorporating the already-existing organisations and following the principle of placing all future international organisations under the patronage of the League of Nations.20 Although a section of the General Secretariat had been established for this purpose under Japanese diplomat Inazō Nitobe (1862–1933), the project was a total failure. Among other things, there was a lack of personnel to coordinate an estimated 300 international organisations. Furthermore, large organisations such as the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property simply refused to give up their autonomy.21

, the League of Nations took the initiative in a field of social policy that had already established itself in the mid-1870s as a global field of politics under the guidance of civil society pressure groups. This movement became a part of international law with the International Opium Convention of 1912.19 In Article 24 of the charter, the explicit attempt was formulated to dissolve the pre-war internationalism in the League of Nations. This was to succeed by incorporating the already-existing organisations and following the principle of placing all future international organisations under the patronage of the League of Nations.20 Although a section of the General Secretariat had been established for this purpose under Japanese diplomat Inazō Nitobe (1862–1933), the project was a total failure. Among other things, there was a lack of personnel to coordinate an estimated 300 international organisations. Furthermore, large organisations such as the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property simply refused to give up their autonomy.21

The League of Nations: "A Great Experiment in International Administration"

The charter of the League of Nations22 also constituted the first 26 articles of the Versailles Peace Treaty and was, thus, inextricably connected with the end of the First World War. Despite broad public support, as the League of Nations had a goal of establishing a peaceful post-war policy, incorporating its name into a treaty that ended a traumatic war was held against the organisation from the beginning. In the long term, the League gave the impression of a peace agency imposed by victorious powers. This was reinforced by the imbalance in the structure of members: Among the great powers, only France and Great Britain were permanent members. The USA never ratified the charter, although President Woodrow Wilson had been among its leading architects . Germany, as the defeated power, was not granted entry until 1926

. Germany, as the defeated power, was not granted entry until 1926 . The Soviet Union entered in 1934, by which time Japan and Nazi Germany had already left.23

. The Soviet Union entered in 1934, by which time Japan and Nazi Germany had already left.23

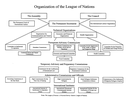

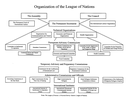

The political organs were the General Assembly of the member states and the Council . This initially consisted of the four permanent members, Great Britain, France, Japan and Italy, together with four alternating members elected by the General Assembly (increased to six in 1922). In 1926, the Council was again expanded, when Germany, as a new member, acquired a permanent seat, and Spain and Poland, in return, each received a semi-permanent seat. "Semi-permanent" meant that Poland and Spain, after the end of their 3-year membership in the Council, could be repeatedly re-elected, whereas the other member states could only be members of the Council once. Both organs passed their resolutions unanimously. This went together with the overlap of their jurisdictions, which constituted a constructional fault in the League. The Council was in the tradition of the European concert of major powers and, thus, pursued the customs of the old diplomacy, whereas the notion of an international parliament was applied in the form of the General Assembly. In this way, the demand from pacifists and proponents of the League for a new, democratised diplomacy was granted.24

. This initially consisted of the four permanent members, Great Britain, France, Japan and Italy, together with four alternating members elected by the General Assembly (increased to six in 1922). In 1926, the Council was again expanded, when Germany, as a new member, acquired a permanent seat, and Spain and Poland, in return, each received a semi-permanent seat. "Semi-permanent" meant that Poland and Spain, after the end of their 3-year membership in the Council, could be repeatedly re-elected, whereas the other member states could only be members of the Council once. Both organs passed their resolutions unanimously. This went together with the overlap of their jurisdictions, which constituted a constructional fault in the League. The Council was in the tradition of the European concert of major powers and, thus, pursued the customs of the old diplomacy, whereas the notion of an international parliament was applied in the form of the General Assembly. In this way, the demand from pacifists and proponents of the League for a new, democratised diplomacy was granted.24

This simultaneity of conventional diplomacy and new political structures left its mark on the League of Nations. Its charter laid down the principle of national sovereignty, whose inviolability was postulated by several articles: Article 10 guaranteed territorial and political integrity, Article 5 demanded unanimity in all resolutions and Articles 11 to 17 regulated the procedures for solving conflicts between member states.25 Contrasting these articles, in Article 22, were the placing of the former German colonies and areas of the disbanded Ottoman Empire within a system of "sacred trust of civilisation", as well as the application of the principle launched by Woodrow Wilson in 1918 of national self-determination. This offered ethnic and religious minorities the possibility to call upon the League of Nations as a mediator in cases of state discrimination or disadvantage.26 The tension involved in putting these principles into practice reflected how unbalanced their relations were with one another: The inviolability of the national rights of sovereignty contrasted with the ambitions of the great powers for territorial expansion. These could, in turn, be restrained by a petition procedure bypassing the nation state, which granted minority and mandate policy to whole populations. This became evident in the case of minority protection. The great powers had explicitly withdrawn dealings with their own minorities from international access; additionally, the scope for action of the section headed by Norwegian diplomat Erik Colban (1876–1956) was limited, despite a number of disagreements in the new states of East Central Europe. This was due to an unclear petition procedure, together with a lack of possibilities of sanctions and checks. The protection of politically or culturally threatened minorities was, in practice, limited by the sovereign rights of states.27 With the mandates, the League of Nations favoured a colonial policy that made use of a rhetoric of trusteeship and a civilising mission.28 Although the mandate powers had to submit an annual report, and the regions under mandate could and did exert pressure on the mandate powers,29 the latter retained sufficient instruments to expand their colonial influence. In doing so, they made use of a language that, in the sense of "imperial internationalism",30 linked the right to political emancipation, transnational cooperation and trusteeship with thinking in terms of the stages of civilization.

The General Secretariat was an innovative achievement that, in many respects, opened up new territory and chiefly pursued the programme of new diplomacy, a policy based on public legitimation. Institutionally, it brought three innovations. To guarantee the independence of the organisation, its officials enjoyed diplomatic rights such as tax and criminal immunity, which were otherwise granted only to diplomats of sovereign states. In addition, in the early 1930s, approximately 700 officials, who came from 40, mainly European, countries, were bound by loyalty to the League of Nations and thus absolved from their loyalty as citizens of their states.31 Article 7 of the charter prescribed equality of the sexes in appointing officials, even though – with the exception of Rachel Crowdy – most women were employed as shorthand typists or copy clerks.32

or copy clerks.32

From the beginning, the information department of the League of Nations was among the large departments. In the manner of a propaganda department, it was responsible for the preparation of information and tasked with ensuring positive press reports. However, its relations with the outside were difficult, on account of the tension between national sovereignty and the will to political community. As the League of Nations only represented the international community of states, the department was required "not to make propaganda under any circumstances, not even propaganda for the League".33 The information department thus performed a tightrope act: On the one hand, it was supposed to shape international public within the world community as imagined by the League, and on the other, it had to limit itself to preparing information on the numerous activities of the League, thus leaving the influencing of public opinion to the national correspondents.34

The League of Nations in the "Golden" 1920s

In the 1920s, the principle of collective security appeared to justify itself by the internationalisation of conflicts. Several frontier conflicts between European states were able to be settled. In the case of the conflict over the Åland Islands between Sweden and Finland in 1921, after protracted investigations, the Council decided that the islands should belong to Finland. The Åland Islands were made an autonomous and demilitarised zone in which the population (of whom the majority were Swedish-speaking) received full political, cultural and linguistic rights.35 There followed the resolution of the conflict between Albania and Yugoslavia in 1921, between Bulgaria and Greece in 1925, and, in the case of the occupation of Corfu in 1923 by Fascist Italy, the Council resolved the conflict and prevented the proclamation of a casus fœderis.36

The partition of Upper Silesia in 1921 into Polish and German regions was an example of the settling of disputed frontiers in ethnically mixed areas. The course of the frontier was fixed following a referendum on the basis of an agreement with 606 articles emphasising the rights of the national minorities, resulting in the establishment of a German-Polish committee to supervise frontier cooperation.37

Refugee aid was one of the most urgent tasks of the League of Nations. In addition to the repatriation of approximately 430,000 prisoners of war from Russia to their home countries, in 1921, Norwegian diplomat Fridtjof Nansen became appointed as the High Commissioner for Refugees on the initiative of the Red Cross International Committee. As such, he managed the situation of an estimated 1.5 million refugees who had gone into exile in cities such as Paris and Constantinople or to the Black Sea. As many refugees had lost their identity papers or had been stripped of their citizenship by the Bolsheviks, the High Commissioner issued them provisional papers. This so-called Nansen Passport was, by 1942, recognised by 52 governments as an official document.38 Alongside the partial repatriation of the Russian refugees, aid was provided for 20 million Russians who were threatened by drought with starvation. The support of the High Commission by the Red Cross, the Save the Children Fund, the Quakers and the American Relief Administration made it clear how dependent the humanitarian actions of the League of Nations were on internationally operating aid organisations. They supplied staff, expertise and logistics, as well as supported the High Commission with their budgets.39

was, by 1942, recognised by 52 governments as an official document.38 Alongside the partial repatriation of the Russian refugees, aid was provided for 20 million Russians who were threatened by drought with starvation. The support of the High Commission by the Red Cross, the Save the Children Fund, the Quakers and the American Relief Administration made it clear how dependent the humanitarian actions of the League of Nations were on internationally operating aid organisations. They supplied staff, expertise and logistics, as well as supported the High Commission with their budgets.39

The Economic and Financial Organisation (EFO) also worked with a lasting effect in war-torn Europe.40 The EFO was founded in 1920, when the continuing unstable economic situation of Central and Eastern Europe had made clear that economic stability would not establish itself automatically but rather needed to be achieved by international cooperation. To begin, the EFO collected data and drew up statistics about individual national economies in Europe. In view of the threatening national bankruptcies of Austria and Hungary in 1922, it developed into an advisory organ functioning as an independent economic factor. At Austria's request, the EFO arranged for fresh credits for the two countries, and a commissioner appointed by the League of Nations placed supervision of the Austrian and Hungarian budgets temporarily under international control. In the 1930s, the EFO, with a staff of 65, was the largest department in the General Secretariat. It was seen as an innovative think-tank whose statistical service played a foremost part in the collection and processing of data. Leading economists, bankers and economic experts who helped to reconstruct the European economic area after 1945 met in its committees, such as Jean Monnet.

The counterpart to the EFO was the Commission for Intellectual Cooperation, founded in 1922, which defined science, education and culture as the common fields of endeavour of the member states. The Commission, to which the International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation in Paris was added in 1926, remained controversial on account of its numerous activities and lack of concrete results.41 The Commission was intended to promote intercultural activity through the circulation of ideas, individuals, cultural goods and knowledge, with the active inclusion of universities and other educational establishments, experts and social groups.42 With the collaboration of prominent intellectuals such as Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and Marie Curie (1867–1934), the Commission complemented military disarmament with "moral disarmament" pean regions were procured, e.g. in the form of the Collection ibéro-américaine, the Collection japonaise, the book series Civilizations and the establishment of the International Museum Office in Paris in 1927.43 The Commission pursued a practical aim with the project to eradicate nationalist or aggressive content from national schoolbooks or textbooks. Instead of the original idea of a unified international history manual, proposals for the revision of schoolbooks in accordance with particular criteria were now sought. This plan was supported in 1927 by an international declaration concerning the teaching of history, but it was only regionally effective on account of the lack of mechanisms for implementation.44

pean regions were procured, e.g. in the form of the Collection ibéro-américaine, the Collection japonaise, the book series Civilizations and the establishment of the International Museum Office in Paris in 1927.43 The Commission pursued a practical aim with the project to eradicate nationalist or aggressive content from national schoolbooks or textbooks. Instead of the original idea of a unified international history manual, proposals for the revision of schoolbooks in accordance with particular criteria were now sought. This plan was supported in 1927 by an international declaration concerning the teaching of history, but it was only regionally effective on account of the lack of mechanisms for implementation.44

The League of Nations in the 1930s

The first international disarmament conference met in Geneva from February 1932 to June 1934. It failed, owing to the persistence of national security interests and the refusal of the European powers to recognise the disarmament scenarios that had been carefully prepared by the Preparatory Commission for the Disarmament Conference since 1926.45 Japan and Germany left the League of Nations in March and November 1933, respectively, in the middle of negotiations full of political tension. This increased the view of observers that the political ambitions of the League of Nations had failed at the same time that the Disarmament Conference had failed to establish a system of collective security. Conversely, the Disarmament Conference made it clear that the League of Nations had been increasingly significant as a contact point for transnationally active pressure groups since its founding. The Conference was part of a disarmament campaign involving the public and, through the media, supported by a broad coalition of groups active throughout Europe, from international organisations for the promotion of culture and education, such as the International Student Service and the PEN Club, and religious humanitarian organisations like the Quakers, to transnational political ones such as the International Federation of Trade Unions.46 This made the League of Nations an attractive meeting point for transnational networks and initiatives in civil society.

The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the Italian attack on Abyssinia (Ethiopia) 1935 confirmed the lack of willingness of the European great powers to make use of the League of Nations as an instrument for keeping the peace. These two events demonstrated how the tradition of European great powers and colonial policies had survived the postulate of democratised diplomacy and the institutional inclusion of non-state interest groups. A symbol of this was the much-reported exit of the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie (1892–1975) from the General Assembly of the League of Nations in June 1936, after Great Britain and France had acceded to Italian plans for annexation. Haile Selassie's appeal to the General Assembly to recognise his country’s right to territorial integrity had remained ineffective.47 The committee of investigation sent by the League of Nations to Manchuria in 1931 to clarify the situation, headed by Lord Lytton (1876–1947), consisted of former British, French, German and Italian colonial officials who, despite a balanced appraisal of the situation, broadly recognised the Japanese interest in regional dominance.48

confirmed the lack of willingness of the European great powers to make use of the League of Nations as an instrument for keeping the peace. These two events demonstrated how the tradition of European great powers and colonial policies had survived the postulate of democratised diplomacy and the institutional inclusion of non-state interest groups. A symbol of this was the much-reported exit of the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie (1892–1975) from the General Assembly of the League of Nations in June 1936, after Great Britain and France had acceded to Italian plans for annexation. Haile Selassie's appeal to the General Assembly to recognise his country’s right to territorial integrity had remained ineffective.47 The committee of investigation sent by the League of Nations to Manchuria in 1931 to clarify the situation, headed by Lord Lytton (1876–1947), consisted of former British, French, German and Italian colonial officials who, despite a balanced appraisal of the situation, broadly recognised the Japanese interest in regional dominance.48

Despite the political stalemate, the technical organisations continued their work. Whereas the Health Organisation left the European refugee scene behind and instead focused its attention on the social conditions of diseases in Africa and Asia,49 the Organisation for Communication and Transit addressed the European affairs, pursuing in its own way a project for European integration with plans for a pan-European motorway and electricity network.50

Towards a New World Order: From the League of Nations to the United Nations

When the Second World War broke out, the Secretariat in Geneva found itself on the fringe of events; the Palais des Nations, the new building that had been dedicated only a few years previously, was used by only a few officials. While the ILO, at the invitation of the Canadian government, transferred its seat in summer 1940 to McGill University in Montreal,51 the EFO and the Department for Transit moved, at the invitation of the Rockefeller Foundation and Princeton University, to the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton. The Interim Secretary-General Sean Lester (1888–1959), who had been installed in September 1940, remained in Geneva with a much-depleted staff.52

The officials in Princeton continued their work. They produced path-breaking studies on economic recovery and paved the way for the Bretton Woods System in cooperation with the US government.53 The Bruce Report of August 1939 had a similarly lasting effect.54 This report was to herald a reform of the League of Nations aimed at strengthening its economic and social activities. The committee, headed by the former Australian Prime Minister Stanley Bruce (1883–1967), proposed placing all social and economic activities together in a Central Committee for Economic and Social Questions. This organisation was to receive its own budget, work separately from the Council and the General Assembly and permit the cooperation of non-members – an initiative aimed above all at the official inclusion of the USA in the economic policy of the EFO.55

On 19th April 1946, the League of Nations formally ceased to exist. This occurred a day after the final session of the General Assembly, which had officially appointed the United Nations, whose charter had already been signed on 26th June 1945 in San Francisco. The General Assembly transferred its powers and duties to the United Nations, including infrastructure and equipment such as the Palais des Nations in Geneva and the library and archives of the League of Nations, ultimately distributing the remainder of its budget to the remaining member states.

However, the League of Nations continued to have an effect beyond its formal end. In particular, the Princeton Mission and the Bruce Report pointed the way to the post-war political order, which was marked by the shift of the political balance of power between Europe and the USA and the North-South conflict. The proposals of the Bruce Committee were taken up by the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations, whose member states and fields of activity are still predominant in the extra-European world. With the move of the main seat to New York, the United Nations overcame the Europe-centeredness of the League of Nations.

Isabella Löhr

Appendix

Sources

[Anonymous]: League of Nations Expires: U.N. to Get Physical Assets: President Hambro's Gaval Sounds Demise of Wilson's Hope – One Vexing Legacy Is Fate of Mandated Territories, in: New York Times (19.04.1946), p. 1, URL: https://nyti.ms/1Y685jU [2023-11-13].

International Labour Office Geneva: Constitution of the International Labour Organisation, in: Dies. (Hg.): Constitution of the International Labour Organisation and Selected Texts, Genf 2010, S. 5–24, online: International Labour Organization (ILO), Constitution of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), 1 April 1919: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ddb5391a.html [2023-11-13].

League of Nations: Covenant of the League of Nations, 28. April 1919, online: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3dd8b9854.html [2023-11-13].

League of Nations: Moral Disarmament: Documentary Material Forwarded by the International Organisation on Intellectual Co-Operation, Geneva 1932.

League of Nations: The Development of International Co-Operation in Economic and Social Affairs: Report of the Special Committee, Geneva 1939.

League of Nations: Trafic de l'opium: Rapports sur les travaux accomplis par la Commission Consultative du Trafic de l'Opium et Autres Drogues Nuisibles à sa onzième session tenue à Genève, du 12 au 26 avril 1928, Geneva 1928.

Literature

Amrith, Sunil: Decolonizing International Health: India and Southeast Asia: 1930–1965, New York 2006.

Ariel, Avraham / Ariel Berger, Nora: Plotting the Globe: Stories of Meridians, Parallels, and the International Date Line, Westport 2006.

Barros, James: The Aland Islands Question: Its Settlement by the League of Nations, New Haven et al. 1968.

Barth, Boris u.a. (ed.): Zivilisierungsmissionen: Imperiale Weltverbesserung seit dem 18. Jahrhundert, Konstanz 2005.

Barth, Volker: Internationale Organisationen und Kongresse, in: Europäische Geschichte Online (EGO), ed. Institut für Europäische Geschichte (IEG), Mainz 12.12.2011. URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/barthv-2011-de URN: urn:nbn://de:0159-2011121203 [2023-11-13].

Borowy, Iris: Coming to Terms with World Health: The League of Nations Health Organisation 1921–1946, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2009, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-05143-8 [2023-11-13].

Burkman, Thomas W.: Japan and the League of Nations: Empire and World Order 1914–1938, Honolulu 2008, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqrcq [2023-11-13].

Clavin, Patricia: Europe and the League of Nations, in: Robert Gerwarth (Hg.): Twisted Paths: Europe 1914–1945, Oxford 2007, p. 325–354.

Eadem: Securing the World Economy: The Reinvention of the League of Nations 1920–1946, Oxford 2013.

Dabringhaus, Sabine: Vom Opiumhandel zum chinesischen Anti-Opium-Kampf: Die Internationalität eines Problems und die Internationalisierung seiner Lösung, in: Periplus 15 (2005), p. 103–125.

Davies, Thomas Richard: A "Great Experiment" of the League of Nations Era: International Nongovernmental Organizations, Global Governance, and Democracy Beyond the State, in: Global Governance 18 (2012), p. 405–423, URI: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/3889 [2023-11-13].

Davies, Thomas Richard: The Possibilities of Transnational Activism: The Campaign for Disarmament between the Two World Wars, Leiden et al. 2007.

Decorzant, Yann: La Société des Nations et la naissance d'une conception de la régulation économique internationale, Brussels et al. 2011.

Dubin, Martin M.: Toward the Bruce Report: The Economic and Social Programs of the League of Nations in the Avenol Era, in: United Nations Library et al. (ed.): The League of Nations in Retrospect: Proceedings of the Symposium, Geneva 6–9 November 1980, Berlin 1983, p. 42–72, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110905854.42 [2023-11-13].

Dülffer, Jost: Regeln gegen den Krieg? Die Haager Friedenskonferenzen von 1899 und 1907 in der internationalen Politik, Berlin 1981.

Erdmenger, Katharina: Diener zweier Herren? Briten im Sekretariat des Völkerbundes 1919–1933, Baden-Baden 1998.

Fachiri, Alexander Pandelli: The Permanent Court of International Justice: Its Constitution, Procedure and Work, London 1932.

Fassbender, Bardo / Peters, Anne: Introduction: Towards a Global History of International Law, in: Dies. (Hg.): The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law, Oxford 2012, p. 1–24, DOI: 10.1093/law/9780199599752.001.0001 [2023-11-13].

Fink, Carol: Minority Rights as an International Question, in: Contemporary European History 9 (2000), p. 385–400.

Fisch, Jörg (ed.): Die Verteilung der Welt: Selbstbestimmung und das Selbstbestimmungsrecht der Völker, Munich 2011, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110446708 [2023-11-13].

Fischer, Thomas: Frauenhandel und Prostitution: Zur Institutionalisierung eines transnationalen Diskurses im Völkerbund, in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 54 (2006), p. 876–887.

Fuchs, Eckhardt: Der Völkerbund und die Institutionalisierung transnationaler Bildungsbeziehungen, in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 54 (2006), p. 888–899.

Geyer, Martin H. et al. (ed.): The Mechanics of Internationalism: Culture, Society and Politics from the 1840s to the First World War, Oxford 2001.

Gorman, Daniel: The Emergence of International Society in the 1920s, Cambridge 2012, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139108584 [2023-11-13].

Gray, William Glenn: What Did the League Do, Exactly?, in: International History Spotlight 1 (2007), S. 2, online: https://issforum.org/IHS/PDF/IHS2007-1-Gray.pdf [2023-11-13].

Herren, Madeleine: Internationale Organisationen seit 1865: Eine Globalgeschichte der internationalen Ordnung, Darmstadt 2009, URL: https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/sites/default/files/medien/material/2011-3/Herren_2009.pdf [2023-11-13].

Housden, Martyn: The League of Nations and the Organisation of Peace, Harlow 2012, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833552 [2023-11-13].

Iriye, Akira: Cultural Internationalism and World Order, Baltimore, MD 1997.

Iriye, Akira: Global Community: The Role of international Organizations in the Making of the Contemporary World, Berkeley et al. 2004.

Kaiser, Wolfram / Schot, Johan: Writing the Rules for Europe: Experts, Cartels, and International Organizations, Basingstoke 2014.

Knock, Thomas J.: To End all Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order, New York 1992, URL: https://muse.jhu.edu/book/64427 [2023-11-13].

Kolasa, Jan: International Intellectual Cooperation: The League Experience and the Beginnings of Unesco, Warsaw 1962.

Kott, Sandrine et al. (ed.): Globalising Social Rights: The ILO and Beyond, London 2013.

Kott, Sandrine: Fighting for War or Preparing for Peace: The ILO during the Second World War, in: Journal of Modern History 86,4 (2014), p. 359–376, DOI: https://doi.org/10.17104%2F1611-8944_2014_3_359 [2023-11-13].

Lake, Marilyn: Art. "Universal Race Congress", in: The Palgrave Dictionary of Transnational History: From the mid-19th Century to the Present (2009), p. 1079, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-74030-7 [2023-11-13].

Laqua, Daniel: Transnational Intellectual Cooperation, the League of Nations, and the Problem of Order, in: Journal of Global History 6 (2011), p. 223–247, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022811000246 [2023-11-13].

Löhr, Isabella / Herren, Madeleine: Gipfeltreffen im Schatten der Weltpolitik: Arthur Sweetser und die Mediendiplomatie des Völkerbunds, in: Norman Domeier et al. (ed.): Zwischen Nation und Weltöffentlichkeit. Korrespondenten im Auslandseinsatz (1890 bis 1990): Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 62,5 (2014), p. 411–424. Löhr, Isabella: Die Globalisierung geistiger Eigentumsrechte: Neue Strukturen internationaler Zusammenarbeit 1886–1952, Göttingen 2010.

MacKenzie, David: A World Beyond Borders: An Introduction to the History of International Organisations, Toronto 2010, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctt2tttsh [2023-11-13].

Maul, Daniel: Appell an das Gewissen Europas: Fridtjof Nansen und die russische Hungerhilfe 1921–1923, in: Themenportal Europäische Geschichte (2011), URL: https://www.europa.clio-online.de/essay/id/fdae-1554 [2023-11-13].

Mazower, Mark: Minorities and the League of Nations in Interwar Europe, in: Daedalus 126 (2002), p. 47–65, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20027428 [2023-11-13].

Paulmann, Johannes: Diplomatie, in: Jost Dülffer u.a. (Hg.): Dimensionen internationaler Geschichte, Munich 2012, p. 47–64, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1524/9783486717075.47 [2023-11-13].

Pedersen, Susan: Back to the League of Nations: Review Essay, in: American Historical Review 112 (2007), p. 1091–1117, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.112.4.1091 [2023-11-13].

Pedersen, Susan: Getting out of Iraq – in 1932: The League of Nations and the Road to Normative Statehood, in: American Historical Review 115 (2010), p. 975–1000, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.115.4.975 [2023-11-13].

Pedersen, Susan: The Meaning of the Mandates System: An Argument, in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 32 (2006), p. 560–582.

Ranshofen-Wertheimer, Egon: The International Secretariat: A Great Experiment in International Administration, Washington D.C. 1945.

Renoliet, Jean-Jacques: L'Unesco oubliée: La Société des Nations et la coopération intellectuelle (1919–1946), Paris 1999.

Rosenberg, Emily S.: Transnationale Strömungen in einer Welt, die zusammenrückt, in: Emily S. Rosenberg (ed.): Geschichte der Welt 1870–1945: Weltmärkte und Weltkriege, München 2012, p. 815–998, DOI: https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406641152-815 [2023-11-13].

Rupp, Leila J.: The Making of International Women's Organizations, in: Martin Geyer et al (ed.): The Mechanics of Internationalism: Culture, Society, and Politics from the 1840s to the First World War, Oxford 2001, p. 205–234.

Rupp, Leila J.: Transnationale Frauenbewegungen, in: Europäische Geschichte Online (EGO), ed. Institut für Europäische Geschichte (IEG), Mainz 26.08.2011, URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/ruppl-2011-de URN: urn:nbn://de:0159-2011080841 [2023-11-13].

Schipper, Frank / Lagendijk, Vincent / Anastasiadou, Irene: New Connections for an Old Continent: Rail, Road and Electricity in the League of Nations' Organisation for Communications and Transit, in: Alexander Badenoch u.a. (Hg.): Materialising Europe: Transnational Infrastructures and the Project of Europe, London 2010, p. 113–143, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230292314_7 [2023-11-13].

Schot, Johan / Lagendijk, Vincent: Technocratic Internationalism in the Interwar Years: Building Europe on Motorways and Electricity Networks in: Journal of Modern European History 6 (2008), p. 196–217, DOI: https://doi.org/10.17104%2F1611-8944_2008_2_196 [2023-11-13].

Skran, Claudena M.: Refugees in Interwar-Europe: The Emergence of a Regime, Oxford 1995, DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198273929.001.0001 [2023-11-13].

Sluga, Glenda: Internationalism in the Age of Nationalism, Philadelphia 2013, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fj199 [2023-11-13].

Steiner, Zara: The Lights That Failed: European International History 1919–1933, Oxford 2007, DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198221142.001.0001 [2023-11-13].

Tooley, Terry Hunt: National Identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the Eastern Border, 1918–1922, Lincoln 1997, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03612759.1998.10528014 [2023-11-13].

Wolf, Willem-Jan van der: The Permanent Court of International Justice: Its History and Landmark Cases, The Hague 2011.

Walters, Francis P.: A History of the League of Nations, Oxford 1952.

Webster, Andrew: The Transnational Dream: Politicians, Diplomats and Soldiers in the League of Nation's Pursuit of International Disarmament: 1920–1938, in: Journal of Contemporary European History 14 (2005), p. 493–518, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960777305002730 [2023-11-13].

Weiss, Thomas G. / Carayannis, Tatiana / Jolly, Richard: The "Third" United Nations, in: Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 15 (2009), p. 123–142, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27800742 [2023-11-13].

Wenzlhuemer, Roland: Die Geschichte der Standardisierung in Europa, in: Europäische Geschichte Online (EGO), ed. Institut für Europäische Geschichte (IEG), Mainz 2010-12-03. URL: https://www.ieg-ego.eu/wenzlhuemerr-2010-de URN: urn:nbn://de:0159-20100921454 [2023-11-13].

Notes

- ^ [Anon.], League of Nations Expires 1946, p. 1.

- ^ Knock, To End all Wars 1992.

- ^ Erdmenger, Diener 1998.

- ^ Clavin, Europe and the League 2007, p. 325–327.

- ^ Cf. e.g. Amrith, Decolonizing 2006.

- ^ Surveys in: Walters, A History 1952; Housden, The League 2012.

- ^ Rosenberg, Transnationale Strömungen 2012; Fassbender / Peters, Introduction 2012.

- ^ See survey in: Pedersen, Back 2007.

- ^ For the concept of the "Third League of Nations", see: Weiss / Carayannis / Jolly, The "Third" 2009.

- ^ Davies, A "Great Experiment" 2012.

- ^ Gray, What Did 2007, p. 2; Herren, Internationale Organisationen 2009, p. 54–65.

- ^ Sluga, Internationalism 2013, p. 37–39.

- ^ On standardisation, cf. Wenzlhuemer, Geschichte 2010; Ariel / Ariel Berger, Plotting 2006; Geyer / Paulmann, Mechanics 2001.

- ^ Cf. on this Barth, Internationale Organisationen 2011; Lake, Universal Race 2009; Rupp, The Making 2001.

- ^ Iriye, Global Community 2004, p. 19–23.

- ^ Fachiri, The Permanent Court 1932; Van der Wolf, The Permanent Court 2011; Dülffer, Regeln 1981.

- ^ International Labour Office Geneva, Constitution 2010, p. 5; Kott, Globalising 2013.

- ^ Rupp, Transnationale Frauenbewegung 2011; Fischer, Frauenhandel 2006.

- ^ League of Nations, Trafic de l'opium 1928; Dabringhaus, Vom Opiumhandel 2005.

- ^ League of Nations, Covenant 1919, Article 24.

- ^ Löhr, Die Globalisierung 2010, p. 161–172.

- ^ Quote: Ranshofen-Wertheimer, The International 1945.

- ^ Walters, A History 1952, p. 64–65.

- ^ Steiner, The Lights 2007, p. 352–353; MacKenzie, A World Beyond 2010, S. 14; Paulmann, Diplomatie 2012, p. 47–64.

- ^ League of Nations, Covenant 1919.

- ^ Fisch, Die Verteilung 2011.

- ^ Fink, Minority Rights 2000; Mazower, Minorities 2002.

- ^ Barth, Zivilisierungsmissionen 2005.

- ^ Pedersen, The Meaning 2006; Pedersen, Getting out 2010.

- ^ Gorman, The Emergence 2012, p. 311.

- ^ Ranshofen-Wertheimer, The International 1945, p. 265–266, 431–432.

- ^ Ranshofen-Wertheimer, The International 1945., p. 367.

- ^ Ranshofen-Wertheimer, The International 1945, p. 203.

- ^ Löhr / Herren, Gipfeltreffen 2014.

- ^ Barros, The Aland Islands 1968.

- ^ Steiner, The Lights 2007, p. 354–359.

- ^ Walters, A History 1952, p. 152–158; Tooley, National Identity 1997.

- ^ Skran, Refugees 1995.

- ^ Maul, Appell 2011.

- ^ On the history of the EFO, see the recently published comprehensive study by Clavin, Securing 2013; Decorzant, La Société 2011.

- ^ On the structure and mode of functioning of the Organisation for Intellectual Cooperation founded by the General Assembly in 1926, see Löhr, Die Globalisierung 2010, p. 173–190.

- ^ Cf. on the concept of cultural internationalism: Iriye, Cultural Internationalism 1997.

- ^ Laqua, Transnational Intellectual 2011, p. 229–233; for details on the activities of the Commission for Intellectual Cooperation, cf. Renoliet, L’Unesco 1999.

- ^ Fuchs, Der Völkerbund 2006.

- ^ Webster, The Transnational 2005.

- ^ Davies, The Possibilities 2007.

- ^ Housden, The League 2012, p. 102–106; Walters, A History 1952, p. 623–691.

- ^ Burkman, Japan 2008.

- ^ Borowy, Coming 2009.

- ^ Schot / Lagendijk, Technocratic 2008; Schipper / Lagendijk / Anastasiadou, New Connections 2010.

- ^ Kott, Fighting 2014.

- ^ Walters, A History 1952, p. 809–810; Clavin, The Reinvention 2013, p. 258–266.

- ^ Clavin, The Reinvention 2013, p. 305–340.

- ^ League of Nations, The Development 1939.

- ^ Ranshofen-Wertheimer, The International 1945, p. 163–166; Dubin, Toward 1983; Clavin, The Reinvention 2013, p. 240–251.

![Rachel Crowdy IMG Dame Rachel Crowdy, a commandant of the VAD [Voluntary Aid Detachment] and her assistant Miss Monica Glazebrook in their office at the Hotel Christol, Boulogne, Schwarz-Weiß-Photographie, 1919, Photographin: Olive Edis; Bildquelle: © IWM (Q 7978), http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194661, IWM Non Commercial Licence, http://www.iwm.org.uk/corporate/privacy-copyright/licence.](./illustrationen/voelkerbund-bilderordner/rachel-crowdy-img/@@images/image/thumb)