(Pre-)conditions

Would it, for instance, be possible to tell a story of cultural and artistic exchange processes between "Europe and the world" that is consistent with the essential characteristics of a historical expansion narrative? Such a story would extend from the Roman Empire of antiquity and late antiquity, which encountered ancient Oriental cultures in the Near East, to the relationship between Arab cultures and the Mediterranean, which accompanied the spread of Islam and essentially led to the so-called "global Middle Ages".1 The transatlantic discovery of America

In a historical perspective spanning several epochs, it is precisely the view of material cultures and the exchange of artistic objects and techniques that offers illuminating insights. A so-called "global art history", which focuses on objects and their circulation, for example, also represents a particularly visible segment of social and economic contact and conflict history. Such a history by definition does not always depict Europe as a permanent center, but rather as the nodal point of a comprehensive global network, and thus fundamentally questions the traditional evolutionary Eurocentric categories and narratives of Western art and history.2

Closely related to this is the questioning of geographical or political borders as categories of order, especially since every border is subject to historical processes and thus "porous".3 Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann (b. 1948) has shown, for example, how changing concepts of geography have already been and continue to be inscribed in the methodological history of art history. On the basis of case studies from Europe and Central Europe, from America, and with a view to Japan, he distinguishes physical, cultural, artistic and other geographies. He observes that the geography of art – including its borders and contact zones – can be closely related to identity negotiations, but it is not necessarily congruent with cultural geography.4 In this sense, the present article does not aim at a linear, empirical history of exchange between "Europe and the world", but rather seeks to provide an exemplary account that focuses on a few moments of exchange between different European architectural and visual arts vis-à-vis "the world". The aim is to identify central concepts, principles and actors of cultural exchange processes in the field of the arts. Furthermore, the following also targets a prospective compatibility with progressive empirical and conceptual canon extensions: In this sense, art history as a history of the migrations of people, concepts and objects can contribute to strengthening the concept of Europe as a historical substrate for ideas, while at the same time repeatedly repositioning and reordering this concept within the framework of an expanded art history of global associations. The changeability and relevance of the concept of Europe can thus be seen in the processes of material cultural exchange.

Conceptual models and terminology

The connecting line between "Europe and the world" called for in the title of this article thus first requires a critical look at some conceptual models and terminologies of cultural studies, which ultimately lead to different readings of a "global" or geo-historically extended art history.5 An important term here is that of Eurocentrism, which in the most general sense is a dominance of European values, norms, metrics, languages and analytical categories. In the context of the arts, this can mean, for example, the canonical over-representation of European artists in art historical narratives, museum collections and presentations or on the art market. Directly connected with this is the higher valuation of art genres such as independent painting and sculpture or of conventions of representation such as mimetic imitation of nature or frontal perspective

Historiography

A teleological understanding of history can be seen here, in which non-European art as well as prehistoric art, for example, remains at a lower level of development, i.e. is partially or completely excluded from the realm of civilized art. The concept of "primitive" or "primitivism" is closely related to this understanding. It was and is often predominantly associated with cultures and artworks from sub-Saharan Africa, from Oceania or the indigenous peoples of North- and South American. By contrast, the Islamic world, India and China, as so-called "Oriental written cultures", are conceded by comparison more of their own historicity and development. These categorizations can arise from anthropological or philological traditions. Art history, though, which deals with visual media, material cultures and their often socially connoted products, also seems particularly susceptible to such hierarchization. Its central historical frames of reference and evaluation are based on provenance- or author-centered narratives, courtly and other elite cultures, and academic or institutionalized aesthetic norms. In practical terms, this is particularly evident from a historical perspective where a non-European culture is then considered to be of higher value or "more relevant," whenever it seems closer to Western categories, for instance in its mimetic imitation of nature, or where courtly cultures can be identified that allow moments of comparison or even direct connections with a "golden age" of European history such as the Renaissance. In a modern, avant-garde perspective, this relationship can be reversed in such a way that the so-called "primitive" is regarded as more authentic and immediate. This turn corresponds to the Enlightenment topos of the "noble savage", which is read affirmatively, but is nevertheless located primarily outside Western civilization. Thus, while the empirical perspective is broadened in the often-used terminological pairing European/non-European, the norm and deviation remain strictly speaking fixed.

In this context, we should also consider the status of non-European cultures within the framework of universal art history, which has been established as a historiographic genre since about the middle of the 19th century. German scholars were often instrumental in this field. Franz Kugler's (1808–1858) Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte, first published in 1842, is regarded as the first overview work with a global perspective. The entire first section is dedicated to the art of non-European "peoples". Together with prehistoric art, however, the art is categorized under the heading of "earlier stages of development".6 In the following decades, art history eventually established itself as a specialist discipline. During this period, the range of methods and subject matter continuously expanded, the latter as a consequence of an increasingly expansionist attitude. Technical progress in imaging and reproduction accelerated the circulation of images, which contributed significantly to the awareness of non-European objects, especially if they were already part of Western collections. The Kugler-influenced format of the handbook continues to be an important instrument of canon formation, as it is always at the intersection of the broader social perception of art. In 1929, for example, a new edition of the Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte was published in Leipzig, which illustrated in a condensed way the standing of art history in general and in relation to the art of the "world" during the interwar period. The sixth and last volume summarizes Die aussereuropäische Kunst (Non-European Art). The chapters "East Asian Art", "Indian Art", "Islamic Art", "African Art", "American Indian Art" and "Malay-Pacific Art" are utilized here as summary categories, which are delineated by qualified European experts (among them the only female author Stella Kramrisch (1898–1993)) on the basis of important museum and collection holdings.7 The introduction of the Asia specialist Curt Glaser (1879–1943) – a Berlin museum director – demonstrates how Ethnographica were gradually turned towards the category of "art" in the eyes of Europeans and at European institutions. He also shows how this development was linked to an idea of form and history of style that largely ignored historical backgrounds and contexts.8 Thus the objects were, so to speak, removed from their contexts of origin at the moment of their "becoming art" and put in closer relation to the European canon, yet they were also reduced to their formal characteristics. This is a clear act of appropriation, in which the cultures of origin hardly retain any individual voice. Here, the incorporation of objects into a supposedly universal discourse was apparently also necessary for keeping the larger theme of "art of the world" flexible. The concentration on formal and technical considerations, accordingly, made it possible to assess and categorize objects of the most diverse provenance – which inevitably led to essentialisms and reductions. The handbook itself illustrates this: Brought together in a single volume are material cultural products of several distant continents or cultures, almost all of which are geographically more extensive than Europe. "Africa", for instance, appears as an undifferentiated major category like "Islam". By contrast, there are five individual volumes for the most important epochs of European art. In such a perspective, European art history thus shows a progression and an inner dynamic, while the non-European themes are more or less supplementary and remain statically bound to rough geographical or culturalist keywords. Such publication practices demonstrate the epistemic imbalance of European art reception compared to the world "outside of Europe".

This imbalance therefore persists even if "the other" is affirmatively acknowledged in the course of the history of ideas and culture – as with the notion of the "noble savage" of the Enlightenment or in the artistic "Primitivism" of the expressionists. It was precisely the comparative methodology of an art history functioning qua a history of style that allowed the aesthetics of the "foreign" to serve as a counterweight in such cases. These so-called foreign aesthetics, for instance, could confirm or catalyze one's own ideas, such as when it came to overcoming the mimetic imitation of nature.9 The concept of "world art", which has been established since the beginning of the 20th century, should be viewed critically against this background. Its genesis, after all, is anchored within a universalistic German-language history of ideas.10 Concepts such as André Malraux' (1901–1976) Musée Imaginaire bear witness to its transnational variations in Europe, the effects of which are still felt today.11

Any attempt to summarize the arts of Europe in relation to the arts of the world within an empirically defined canon and, moreover, as a constitutive element of a linear world or European history should therefore no longer be taken seriously. In recent decades, postcolonial regional and cultural studies in particular have made a significant contribution to widening perspectives. These include, for example, the discussions on entangled histories (histoires croisées),12 cultural exchange,13 contact zones and object biographies.14 By taking up and developing such conceptual models, art history, museums and artistic practice allow for a more differentiated view of the reciprocity and complexity of exchange processes that go beyond binary notions of "Europe and the world". At the same time, the primary contexts and the European histories of art works can be critically examined in relation to each other. Such questions demonstrate the necessity of an interdisciplinary approach. If the aim is to view the world not only from the vantage point of Europe, but to place diverse, differentiated cultures into reciprocal relations with European art traditions, then the linguistic, historical and cultural contexts relevant to this task require a broad spectrum of perspectives and competencies. Their close cooperation with neighboring disciplines such as ethnology, anthropology, history, area studies, and other fields of study seems obvious. The field of Mediterranean Studies offers examples of how art and art history are productive in such connections. Art historical approaches dealing with the mobility of objects and artistic practices have contributed significantly to the expansion of historiographical and geographical perspectives. Not only is the Mediterranean region itself read here as a direct contact zone between a geo-historical and cultural North and South, but it is also situated in a history of extensive global references.15

The model of "multiple histories" is closely connected to such a project of decentring art history, although less geographically than conceptually. It assumes that individual objects or events can be explained from different pre-histories – or that there can be different views of history simultaneously. The idea of multiple modernities has proved fruitful especially for the colonial and post-colonial period, and not least in art history.16 The accompanying expansion of subjects and questions finally corresponds to the decentering of Europe as defined and promoted by postcolonial authors.17 The thematic focus of this article is to be understood against this broader background: The basic demand to present an art history about "Europe and the world" – i.e. with a reception primarily originating from Europe – is, firstly, only one of many possible perspectives within a larger constellation. Secondly, "the world" as a frame of reference is so universal that any attempt at a comprehensive representation would inevitably result again in essentialisms and generalizations. This may be one of the reasons why there are scarcely any truly up-to-date overall representations of "global art history".18

Entangled histories: The example of Europe and the Islamic world

Europe: Entangled art histories and longue durée

The examples used in the following to illustrate an exchange and contact history mainly refer to the relationship with the Islamic world. This choice admittedly coincides with a special interest of the author, but it is plausible because of the historical continuity of contacts, resulting from the relative geographical proximity. The idea of entanglement is to be taken quite literally, even geographically, as both historical evidence and the living continuity of Islamic cultures can be found in Europe today. This includes the sites and influences of the Al-Andalus or Fatimid Sicily, the western margins of the Ottoman Empire on the Balkans, and today's lively and diverse Islamic diaspora culture. Many of the examples are much older than the modern concept of Europe, but still have an impact today. For instance, the discussion about the principle of a Convicencia of cultures, founded in the history of Al-Andalus, is closely connected with Spain's modern identity, and it shapes to this day the reception of important monuments like the Alhambra

Medieval cultural contacts: divided elite cultures, hybrid objects

One object that is linked to the above-mentioned questions is the so-called Arenberg Basin, a 50-cm-diameter brass basin with silver inlays

The "global" dimension of early modern times

There is direct continuity here with the global dimension of the early modern era. This early period of European expansion on a large scale did more than just literally expand the worldview through the discovery and colonization of both American continents. The imperial, mercantile, and scientific endeavors of this time also led to increased exchange in numerous ways. Where Europeans encountered imperial structures and written cultures, the encounter tended to be more reciprocal. Thus as only one aspect of early modern exchange history, cabinets of curiosities of the Renaissance thereby became the epistemic refuge of a comprehensive humanistic conception of the world, in which naturalia and artificialia of the most diverse historical and geographical provenances met

This does not in any way imply the idealized image of a historical cultural exchange without conflict. On the contrary, object-related case studies of artistic encounters seek to express the natural awareness that there is virtually always a wide range of gray and intermediate tones between the aesthetics of difference, convergence and assimilation.

Modern paradigms: Nation, Collection, Provenance

The term "Europe" in its modern sense, however, derives primarily from the European order influenced by nations since the Age of Enlightenment: a period in which international exchange accelerated rapidly for political and technical reasons and which is to be understood as the most immediate prehistory of our present globalized world. In this context, the writing of particular histories of individual nations, their art histories and institutions in relation to the "world" might seem obvious. Imperial and colonial aspirations are among the most formative realpolitik tendencies of this period and are closely linked to the narratives of nation-building. During the heyday of imperialism and nation-building, the world's fairs established themselves in equal measure as commercial centers for art and trade. They introduced Western goods and techniques to the world, while at the same time the arts and crafts of non-European cultures appeared here as a model that was to contribute to a renewal of the applied arts in Europe.25 In the 19th century, this was an important route for non-European objects to reach art and ethnographic collections and finally art museums.

Altogether, a critical examination of the museum, collection and provenance histories of individual European countries has indeed brought to light a number of new insights in recent years, not least into artistic Orientalism or the collection and archaeological excavation practices of national museums and institutions.26 Above and beyond the example of the Near East, the numerous qualitatively and, in all their details, highly diverse problems of provenance and restitution have come to light, which are currently among the most virulent topics of national cultural policy in many European countries. To mention just two particularly prominent examples of what has become a wide debate: Firstly, the famous bust of Nefertiti in the Neues Museum in Berlin

More in-depth analysis is required in each individual case for this group of topics. In any case, it highlights the asymmetries that have privileged Europe's contact with the world over the centuries, and which are still only slowly coming to the attention of experts, institutions and the general public.29

Translation concerns: Art terminology, hierarchies, categories

Without losing sight of such necessary distinctions and open questions, it is precisely the historically established, trans-nationally overlapping currents and tendencies that are of interest. They increasingly raise the question of the extent to which there was or is a characteristically "European" perspective across national narratives and practices. The field of art history and artistic practice seems predestined to illustrate such questions in terms of the history of ideas. On the representational level, however, there arises an additional conceptual problem: How can we talk about artistic exchange processes when the traditional Western concept of art defies unambiguous intercultural translation and is inherently unstable over time? To demonstrate this, we can again turn to the example of Islamic or Arabic art: The Arabic equivalent for "art" is fann, in the plural funun. Nonetheless, it carries other connotations, since it refers to a genre of knowledge rather than to an idealistically formed aesthetic category.30 This translational confusion may gradually lose its significance in the face of a modern and postmodern concept of art that is not subject to boundaries. In the historical frame of reference, however, this constellation is reflected when looking at the objects. This is especially true if architecture – a field with its own semantics – is left out. While the main works of a European canon are mainly comprised of large-format painting, sculpture and statuary, the historical Islamic culture finds its climax in works of miniature and applied arts: The output is more or less characterized by carpets

The idea of "Islamic art" is not inscribed per se in many objects of Middle Eastern provenance. Rather, it originated in the eyes of Western collectors and art historians, who devoted more and more attention to it since the turn of the 20th century.31 And, in the process, they often removed it from its cultural and life-world contexts, to which the inherent mobility of such objects contributed significantly.32

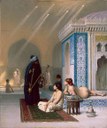

On the other hand, non-European artists simultaneously began to study at European academies and institutions, whereby artistic formats such as the salon and academy were spread to metropolises around the world. This phenomenon could be traced back to local initiatives as much as to the missionary conscience of colonial powers. A telling example of such entanglements, for instance, is Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910). He studied law and painting in Paris; around the turn of the twentieth century, he founded an art academy in Istanbul and also played an important role at the Ottoman antiquities department. His paintings, which at first glance appear classically orientalizing, are aimed at a Western audience. At the same time, they transcend the romanticizing cliché and are often testimonies to the importance of historical cultural heritage for a modern Ottoman identity

Thus an important finding from such examples that can be applied to other variants of transcultural encounters is that the exchange with other cultures challenges the categories of Western art reception: Under Eurocentric conditions this leads to a hierarchization, to the assumption that the great independent art forms only reached their full bloom in Europe. Ideally, however, it can also help to challenge rigid distinctions between "high" and "applied" art in a fundamental way.

Conclusion and outlook – towards an art history of constellations

Can we arrive at an overarching consensus from these reflections on artistic and material-cultural relations between "Europe and the world"? This article began with the following observation: The more histories of entanglement, contact and exchange come to the fore, the less (art) history can be told in a linear fashion. The traditional universal ordering principles moreover become more problematic, such as those suggested in the handbooks of the 19th and early 20th centuries, partly with far-reaching effects up to our time. Today, the fact that objects, artworks, actors and artistic practices move across borders is assumed to be essential to a "global" contemporary art world – even though these "cultural flows" are also marked by economic, political, and ideological asymmetries. This can be described as a state of increased – albeit historically based and evolved – complexity. One possible answer to this could be thinking in constellations. The meaning of the term "constellation" is derived from its use in astronomy: The observation of stars has led to the description of relationships and patterns that are not necessarily inherent in the cosmos itself, but are defined from the observer's point of view of the Earth. Since every act of orientation requires a fixed point, the concept of constellation implies, firstly, a strong hierarchical order, a defined and directed point of view. Thinking in terms of constellations is moreover characterized by a dynamic temporal and spatial dimension, since it operates with the idea of change in the sense of a cyclical, repetitive order. Thus the concept of the constellation could provide a useful figure of thought for the study and analysis of material culture and its epistemic rules of perception. In the field of visual and art historical studies, it can be used to describe artistic manifestations that are not only related to each other, but also to the world. It can also describe them across time, without necessarily implying either predestination or teleological determinism. Accordingly, the temporal and spatial dimension implied in the historical understanding of the concept of constellation becomes increasingly dynamic, potentially even "chaotic" and multidirectional in its modern interpretation. It is here that its potential for expansion into the field of cultural difference or intercultural dynamics becomes apparent. The curator and art theorist Okwui Enwezor (1963–2019) has described the paradigm of a "post-colonial constellation",34 which consists of dichotomies and relationships. These relationships connect areas of subjectivity and creativity and transcend the definitions of art and its autonomy that have shaped Western discourse up to the modern age. Starting from this paradigm, exhibitions and curatorial positions, especially in the postcolonial context, become the substrates of a veritable "age of constellation",35 which capture the movements of actors, objects and ideas. To supplement this, Monica Juneja (born 1955) emphasizes that a view of art that conceives of transculturality as reciprocal and interwoven is not only specific to modernity, but also expands the view of historical constellations.36 The concept of an art history of constellations thus offers the potential to limit the power of overarching hierarchical views and linear perspectives across historical epochs or caesuras. It can thus supplant the panoptical, directed gaze that has historically long been a dominant feature of European visual culture.37 A changed awareness of the foundations of our understanding of art thus becomes decisive for historiography, and for the present and future of exchange processes in art.