Beginnings

The practice of putting 'exotic' people on display began in Europe in the early modern period, when European explorers made their way to every corner of the globe. Sailors brought people with them from the newly explored areas, much as they might present foreign objects, plants and animals to prove the exoticism and wealth of previously unknown countries.1 These 'exotic' people were then exhibited by their 'discoverers' at royal courts or public fairs. Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) himself brought seven 'Arawak Indians' of the West Indies home to Europe from his first trip. Among the 'trophies' Amerigo Vespucci (1451–1512) acquired on his travels through America were more than 200 natives, who were subsequently exhibited at fairs in Spain.2 A great number of these – usually captive – people already died during the voyage to Europe. Furthermore, even those who made it to Europe had little chance of returning to where they had come from. Frequently, they could not cope with the alien world, suffering from homesickness, reacting aversely to the unusual food and dying of diseases unknown to them.

Along with the presentation of individual human beings, major exhibitions were organized from the 16th century onward. Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) thus reports of a village populated by the Brazilian Tupinamba tribe which was established in Rouen in 1533.3 Such exhibitions were rare in Germany up until the 19th century. It was not until 1870 – following the passage of nationwide itinerant-trade regulation after some of the greatest upheavals in Germany's history – that travelling exhibitions gained popularity and large-scale, regional shows became possible.4 At the same time, changes took place in the larger markets, as sales and trade events with occasional side entertainment programs became fairs equipped with every conceivable kind of attraction.

In 1874, Carl Hagenbeck (1844–1913) organized the first major 'Völkerschau' which would become the model for all those that followed. The 'Laplander Exhibition' not only showed the people of this region, but also put them into the context of their native living conditions. Hagenbeck procured livestock, such as reindeer, original tents, tools and sleds, in order to make the exhibition as authentic as possible. His spectacle enjoyed great success abroad as well, for example in France, where elements of the 'Völkerschau' were an essential part of the 1889 Paris World Exhibition.5 Until the First World War, the business of 'exotic' people boomed in Europe.6 It met its demise after the war, however, as business contacts were severed between the agents abroad and the local organizers. In Germany this happened mainly due to the country's loss of its colonies. With the rise of the entertainment industry in the 1920s, the 'Völkerschauen' gradually disappeared from the European scene altogether.7

The structure of a 'Völkerschau'

By the end of the 19th century, Carl Hagenbeck had brought the 'Völkerschau' to an unprecedented level of sophistication. Using earlier shows he had seen as his point of departure, Hagenbeck now planned larger exhibitions with more people and animals. He also had elaborate scenes put together to recreate, for instance, temples and bazaars. The process of implementation also became more tightly organized, as Hagenbeck used every available means of advertising to publicize his shows. In addition to the usual posters, these included newspaper ads, ostentatious processions through the city and promotions with discounted ticket prices.8 As a consequence of the commercial success of Hagenbeck-type exhibitions,

Generally speaking, a 'Völkerschau' needed to combine three elements in order to be commercially successful. First, it had to make use of existing clichés – that is, to show the people in a way that corresponded to the public's expectations. Second, to generate authenticity, it had to connect these stereotypes to the public's everyday experience. For instance, the 'savages' might be shown as parts of a family. As a result of this association with everyday experience, the audience could compare the known to the unknown. Finally, the third element was the specific feature that would draw the audience to this particular exhibition. Every show accordingly required an element that was unique – something unexpectedly new that made it stand out from the rest.

Exhibitors looked for this unexpected novelty among the different indigenous peoples, who therefore had to have certain qualities in order to participate in a show. First and foremost, the people on display had to stimulate the European imagination. For this to occur, they either needed to be recognized as very primitive and close to nature or to be well-suited to picturesque depiction. The life of the 'exotic' people moreover had to generate a certain air of excitement among the visitors.9

After the show's organizer had decided on a particular ethnic group, the process of selection and recruitment would begin six months prior to the opening day. Recruitment was mostly managed by individuals who were also full-time animal-dealers and took care of this additional assignment on location. The agents made an effort to recruit as many different representatives of the population as possible, i.e. women, men, children and the elderly. Only in this way would it later be possible for the European audience to get an impression of the native people's family life. The exhibitors also tried to put their groups together in a way that was at once compelling and heterogeneous. Above all, they searched for special representatives of the people that either coincided with the European beauty ideal or represented the type of 'primitive man' that seemed especially repulsive. Beyond this, the people on display were not to be timid or reserved, but should rather take the initiative and make contact with the visitors.

People with special abilities were prized most, including those who had mastered a craft like ivory carving, or were performers, jugglers or artists. They had the advantage of usually already being accustomed to dealing with audiences and also, at least to some extent, enjoyed being on stage. Indeed, the participants in the 'Völkerschauen' should not be merely viewed as helpless pawns of European despotism, even if the arrangement could not have been made without their freedom being sacrificed. Quite a few people from the colonies readily accepted to take part in exhibitions in Europe because of financial motives. Some even returned back to their homes after a few years wealthy, albeit having generally been paid no more than a fraction of the show's revenues.10 After the recruitment process, a contract was settled between the supplier and the assembled people under the supervision of local authorities. This was to ensure that the group would be adequately provided for during their stay abroad and that they could expect a safe return. In addition, the contract regulated the group's working hours, pay, tasks and medical care.11 Before leaving, all members of the group had to be vaccinated and supplied with passports. The vaccination of the participants in the 'Völkerschauen' became mandatory after a number of groups had almost completely fallen victim to measles, smallpox and tuberculosis during their stay in Europe. Despite the vaccinations, however, there was a risk that the participants might ruin their health due to the exertions of the trip or that they might carry European diseases with them on their return home.

Between 1875 and 1930, about 400 groups were shown at 'Völkerschauen' in Germany. At least 100 of them were organized by Hagenbeck.12 The majority of the groups came from Asia, mostly Ceylon, Samoa and India. African groups for the most part came from Somalia, Nubia, Cameroon and Dahomey. Shows dealing with 'exotic' northern countries exhibited Eskimos and Laplanders.

When putting together the 'Völkerschauen', the organizers basically had a choice between three exhibition types. They could present the group in a native village, permitting the visitors to stroll through it and participate in the 'real' life of the people. If the organizer, however, opted for a circus-like display, the focus was less on showing everyday experiences than on giving visitors an acrobatic and artistic program with a set sequence of performances. The third type of exhibition was the 'freak show', in which the organizer highlighted the people's physical otherness.

William Frederick Cody, aka Buffalo Bill (1846–1917)[

As in the case of Buffalo Bill, who set up his shows in circus-like encampments, circuses served as venues for other exhibitions. Frequently, 'exotic' people were shown in so-called 'sideshows'. The first sideshows emerged in the 1840s in America, reaching Germany in the second half of the 19th century. There, for instance, a small travelling menagerie, the precursor of the Circus Krone, was supplemented by a 'Negro troop' in 1870.14 Of further importance was the Munich Oktoberfest, which became the central location in the city for 'Völkerschauen'. Moreover, 'exotic' people could also be shown in panopticons, which were actually venues for showing waxworks and early films. Just the same, the most popular locations for 'Völkerschauen' were zoological gardens.

Advertising and mode of presentation

The mode of presentation of the 'Völkerschauen' can be understood as reflecting a recursive 'cycle of stereotypes'. Prejudices that were already ingrained in the public were activated by a show's advertisement such as its posters. These were later affirmed in the presentation, where the visitors were then encouraged to form new stereotypes.16 This mode of presentation meant that the planning of a 'Völkerschau' in fact had little to do with showing representatives of a group of people as they really lived or with breaking down the public's prejudices. On the contrary, the greatest emphasis was put on fulfilling the public's expectations in the most spectacular way possible. 'Authenticity' was only important insofar as the audience recognized the presentation as being authentic. To be sure, a comparison of the exhibitions to theatrical performances seems appropriate: the visitors paid admission to view a 'piece' (the people of the particular show), which was staged by a director (the organizer) in a certain way (such as a 'native village'). For this purpose, he had selected suitable 'actors' who learned a text (the sequence of the program) and wore costumes (the alleged or actual attire of their people). The scene was complemented by stage design, which included painted walls, huts, tents and specific props for the particular groups, which is to say, animals and tools.17

In order to bring the show to the widest audience possible, a major advertising campaign was launched in its run-up. It started with the selection of an exciting title, which, in combination with the appropriate poster illustrations, would arouse the public's curiosity. The organizers thus stimulated the public's imagination with exhibitions like 'Wild Africa', 'Negro Wakamba Warrior Caravan', 'First Laplanders of the Arctic', 'Amazons Corps' or even 'Gorilla Negroes'.18 When the exhibition's participants finally arrived at the event's location, magnificent processions were held in the city. At the venue itself, eloquent barkers exhorted the public to enter the show. Now and again, there were also special promotions: Buffalo Bill, for instance, organized an 'Indian Breakfast' with his Wild West Show in 1885, where curious onlookers were served charcoal-grilled beef eaten with a sharpened wooden stick.19 At Hanover's Kanak Show in 1931, which dealt with the inhabitants of the French colony of New Caledonia, visitors could buy 'Kanak roast' prepared in a 'Kanak oven' (pork roasted in an earthen oven).20

Posters – a great variety of which are preserved today in archives – remained the single most important medium of advertising. An analysis of these 'Völkerschau' posters makes it possible to reconstruct what elements had to be used on a poster to evoke certain associations and arouse the viewer's desire to visit the current exhibition.21 The posters, accordingly, hinted at the unmistakable novelty of an exhibition and what distinguished it from all others. Each poster can be systematically assigned to a particular ethnic group and more or less reflects the stereotypes that were cultivated in the late 19th and early 20th century about various world populations. In this case, the 'exotic' people are divided into the following subgroups: primitive man, Africans, Arabs, people from the Far North, Indians, Sinhalese, Native Americans and Pacific Islanders.

The designation of 'primitive man' referred to all those peoples around 1900 that were, from the European perspective, uncivilized and backward. These included Fuegians, Patagonians, 'Hottentots' (South Africans and Namibians) and 'Austral Negroes'. Since these people, according to the general prejudice, culturally lived in the Stone Age, their primitiveness was especially emphasized in the posters. The people depicted were mostly naked, showed savage gestures and expressions and appeared to lack any civilizational conditions, such as religion or social institutions.22

Africans – in this case strictly black Africans – were certainly viewed as only being slightly more advanced, yet the posters focussed on an altogether different aspect. People from the 'Dark Continent' were considered as remarkably savage. To emphasize this quality, the posters usually showed them with weapons

Arabs were portrayed in an entirely different manner. Despite their regional proximity to the Africans, they were perceived in another way. Arabs were not viewed as a 'primitive people', but as a 'civilized nation'. Posters lured visitors with tales from the mysterious 1001 Nights (1300–1401)

Pacific Islanders, however, the posters suggested, were to be envied in every respect. Between the coconut trees, the blue-green water and the warmth of eternal summer, they lived in an earthly paradise. For this reason, these people were regularly presented as friendly, gentle creatures with a sunny disposition who did nothing all day but sing, hula dance and celebrate festivals. The women in this group often appeared bare-chested, wearing only loincloths and flower garlands. Whereas in the Europeans' eyes Arabs typically conducted business in bazaars and Africans primarily fought, the South Sea Islanders did nothing of either kind: they were exclusively devoted to their games and amusements.25

In the 'Völkerschau' posters, ethnic groups from North America appeared as 'Indians'. The organizers thus made no distinction between the continent's numerous tribes. 'Indian' always referred to the Indians of the Great Plains, as the Germans knew them – or presumed to know them – from the novels of Karl May (1842–1912)[

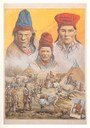

The people from the Far North and northeast included the 'Kalmucks' from the region between Volga and Don, and 'Eskimos' and 'Laplanders'

Only Indians and Sinhalese were rated culturally higher in the 'Völkerschauen' than even the northern peoples. The latter were the largest population groups on the island of Ceylon, which was renamed Sri Lanka in 1972. Their culture was regarded as foreign, but still perceived as being on par with high European culture. In contrast to other ethnic groups, the people of these groups were depicted in all facets of their daily life: they worked or practiced their culture and religion. The focus of many 'Völkerschauen' was accordingly to present the magic and mysticism of an alien culture to European audiences.28

'Völkerschauen' and colonial propaganda

Historians have repeatedly written that the display of 'exotic' people was supposed to encourage interest in the current colonial policies.29 Certainly, colonial exhibitions served to promote German colonization. At the 50 colonial exhibitions that took place 1896–1940, however, virtually no human beings were put on display. Only two of these state-organized shows actually presented people from the German colonies: the Erste Deutsche Kolonialausstellung in Berlin in 1896 and the Afrika-Schau, which took place between 1935 and 1940. Apart from this, the colonial exhibitions mostly resembled trade shows. They were supposed to show new inventions from and for the colonies, and illustrate the lives of the German settlers there.30 The German colonial propaganda also did not generally avail itself of the 'Völkerschau' concept of activating already existing stereotypes. Had there been an interest in showing a foreign population in an 'advertising campaign' for the German colonies, it would have had to present the people as being in need of civilizing. The organizers would have had to explain in their exhibition the reasons for the colonization. One explanation might have been that the superior German civilization was supposed to bring the 'savages' culture. This concept would hardly have been well-received at 'Völkerschauen', however, because the spectators neither wanted to be subject to colonial propaganda nor see civilized 'savages'. Their primary interest was in experiencing a genuine 'exotic' adventure. To this end, presentation concepts in the style of the novels of Karl May and 1001 Nights were more appropriate.

In fact, German Chancellor Chlodwig Carl Viktor, prince of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1819–1901), and the Colonial Council issued a law in 1900 prohibiting the 'export of natives of the colonies for purposes of exposition'.31 Rear Admiral Franz Strauch (1846–1928) commented on the reasons for it in advance in the Deutsche Kolonialzeitung. He noted that, despite the acquisition of the German colonies, 'Völkerschauen' had already been taking place for a long time in Germany and were not aimed at educating the public, but in making money for their organizers. At the same time, 'Völkerschauen' exerted a deleterious influence on the exhibited people. Because it could have done serious harm to the delicate relationship of the 'natives' to the colonialists, it was to be avoided.32 The 'Völkerschau' organizers' lack of scientific rigor along with the colonial masters' concern about the reputation of the Germans and the public opinion in the 'protected areas' also spoke strongly against merging the 'Völkerschau' with German colonialism.

'Völkerschauen' and science

For the academic world, 'Völkerschauen' also had a practical use beyond mere entertainment. Experts from various disciplines, such as anthropology, cultural anthropology, prehistory, medicine and anatomy, took advantage of the exhibited people as objects of research. There were a number of reasons for this practice. 'Exotic material' was difficult to obtain for the scientists. It was not only always associated with expensive travel, but many researchers were also denied access to local human research subjects because of the language barrier. Therefore, the 'exotic' people brought to Europe by the exhibitors were a good alternative to undertaking risky, life-threatening and potentially unproductive travel. Already in the 17th, 18th and early 19th century, scholars showed keen interest in the first exhibited 'exotic' people. After Hagenbeck had entered the 'Völkerschau' business, the cooperation between organizers and scientists intensified, especially with the founding of the Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte in 1869.

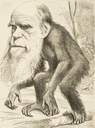

The physical anthropologists had particular interest in 'exotic' people, whose bodies they measured in lengthy procedures. Drawing on the work methods of disciplines such as botany and zoology, the anthropologists of the late 19th and early 20th century attempted to describe the people, to classify them racially and to explore relationships between the individual races. This meant securing as much anthropological comparative material as possible through writing and drawing.34 The scientists hoped to gain insights into the history of mankind from the analysis and synthesis of the measurement results, for they assumed that the 'primitive peoples' belonged to a lower level of development than the 'civilized nations'. They accordingly wanted to find the 'missing link' between apes and humans sought by Charles Darwin (1809–1882)[

The collaboration between academia and the organizers of 'Völkerschauen' was not only advantageous to researchers. When renowned scientists confirmed the authenticity of a show, the exhibitor was able to characterize his event as an educational program. If a 'Völkerschau' had a provably educational quality, the amusement tax, which could be up to 40 per cent of gross revenues, was omitted. In addition, the organizers did not need to apply for itinerant-trade credentials.36 The scientific interest in examining 'Völkerschau' participants declined after the turn of the century. This was due, on the one hand, to the fact that the exhibitors increasingly showed 'ragtag' groups which obviously lacked the necessary authenticity for science. On the other hand, the insight increasingly took hold among researchers that both ethnology and anthropology should be practiced on location.37

The end of the 'Völkerschau'

The 'Völkerschauen' slowly began to disappear from the fairs and festivals at the beginning of the 1930s. In 1931, Hagenbeck's Kanaks of the South Pacific at the Munich Oktoberfest was the last exhibition before the Second World War.38 The same year saw the death of Carl Gabriel (1857–1931) who had organized 'Völkerschauen' in Munich for decades. At the same time, the Nazis' influence grew, and they were themselves divided over the immigration of foreigners who were to appear in exhibitions. Some wanted to use 'Völkerschauen' to conduct colonial propaganda, as Germany had been forced to relinquish all of its colonies after the signing of the Versailles Treaty following the First World War. Others were rather critical of this propagandistic aspect, since 'Völkerschauen' always presented the possibility of contact – a mixture of 'blacks' and 'whites' or 'a commingling of the races'.

Whereas the sight of non-European people in earlier decades had given rise to ridicule, members of 'exotic' peoples were seen as a threat under Nazi rule. Even at the Afrika-Schau in 1935, pains were taken to have the Africans exhibited together in a manageable group. The general stage ban for 'blacks' followed in 1940.39 Nonetheless, the reasons for the disappearance of 'Völkerschauen' should not be sought in the political context alone. As a commercial mass medium of popular culture in the 1930s, film became a strong competitor to the exhibitions of 'exotic' people. Exoticism also played a large role in the film of this time. The medium could convey the subject even more authentically than in the 'Völkerschauen'. Film picked up on the recursive quality of the exhibitions' cycle of stereotypes, only to deepen them further with their own means. The roles of 'exotic' people in the shows were now taken over by actors and extras. For its part, the audience was able to experience the adventure of foreign lands in elaborately concocted plots.40

After the Second World War, individual 'Völkerschauen' once again appeared sporadically. A Wild West Apache Show (1950) and the Hawaii 'Völkerschau' (1951 and 1959) thus took place at the Oktoberfest. These exhibitions, however, were no longer able to achieve the same level of success as their predecessors.41 Film had become too powerful a rival. Other factors, however, diminished interest in the 'Völkerschauen' as well. In the 1950s, the emergence of long-distance tourism made 'Völkerschauen' rather unnecessary for a portion of the population. 'Exotic' people could now be admired in person, on location and in their authentic environment. Once it became affordable to go to where the adventure was, it was no longer necessary to have it brought from elsewhere to one's home country. The increasing criticism of the exhibition of 'exotic' people and the Europeans' changed attitude toward non-European cultures caused the 'Völkerschau' concept to eventually become obsolete and disappear altogether.