Introduction

By focusing on a wide range of visual imagery, this article places the monster-slaying narratives of the strongman Hercules within appropriate early modern contexts. It traces the modern image of Hercules embodying the triumph of good over evil to republican Florence during the early Renaissance (2). It then shows how another model of virtue – that of the young, contemplative Hercules choosing the hard path of virtue over the easier path of pleasure – was used to educate elite young men (3). This is followed by a section on the practice and theory of art. Certain examples of classical sculpture such as the Farnese Hercules were held up in academic training as formal models to be copied and emulated in works of high art. Yet in his various victories over evil, in his forceful heroic interventions and in his judicious choices, the figure of Hercules was still predominantly associated with the princely ruler (5). This model began to break down at the time of the French Revolution, when the French people at its most militant turned the semi-divine hero into a symbol of national unity. The last section (6) deals with extreme and harmful inflections of the model in which the hero's extraordinary strength is out of control, the object of both horror and ridicule. At the turn of the 19th century, the classical tradition came to be translated into visionary, subjective moments of beauty and of beauty threatened.

Hercules in Florentine Republicanism

In the 13th century, Hercules first appeared on the seal of the city of Florence, which, according to an early source, was inscribed with the words: "Hercules clava domat Florentia prava" ("Florence subdues depravity with a Herculean club").1 On his death, Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), chancellor of the Florentine Republic before the rise of the Medici, left an unfinished commentary on Hercules in which the mythic hero is made into an example of the active, virtuous life.2 The figure of Hercules features four times in the reliefs decorating a left inner jamb of the cathedral's portal – first in full length, then fighting the lion, the hydra and Antaeus . These motifs may plausibly have religious as well as civic connotations, signifying victory over evil. In its public sculpture and as emblems of civic identity, republican Florence depicted biblical heroes such as David and Judith who had likewise fought, slain and overcome the evil enemy.3

. These motifs may plausibly have religious as well as civic connotations, signifying victory over evil. In its public sculpture and as emblems of civic identity, republican Florence depicted biblical heroes such as David and Judith who had likewise fought, slain and overcome the evil enemy.3

The iconographic presence of Hercules in Florence was given a major boost by three large paintings showing the same monster-slaying episodes as those on the Duomo portal jamb. Commissioned from the artist Antonio Pollaiuolo (ca. 1429–1498) around 1460 for the sala grande of the Palazzo Medici, each canvas was over three metres high.4 However, Medici patronage of these subjects sat uneasily with the Republican associations that had already been forged. In 1497, after the fall of Piero di Lorenzo de' Medici (1472–1503), the three canvasses were transferred to the Palazzo della Signoria, home of the re-established Florentine Republic. Possibly restored to the Medici in 1512, the works disappeared from view in the later 16th century and have been lost ever since. We owe our knowledge of them partly to written descriptions. In praising the scenes, Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) focused on their realistic depictions of fighting anatomies, gestures and expressions.5

Furthermore, two small copies of the Hercules and the hydra and the Hercules and Antaeus by Antonio Pollaiuolo himself give us a clue about the appearance of the full-sized paintings. Despite their small scale, the panels are unambiguous in their display of menace, power and masculine aggression. In these struggles to the death, monster and tyrant are overcome through the strength of the naked, muscular hero. Squeezing the last breath out of his opponent, Antaeus, the son of Poseidon and the earth goddess Gaia, Hercules lifts his adversary off the ground, the source of his foe's strength. While sculptural reliefs on antique sarcophagi may well have provided the artist with visual precedents for the locked-in movements of figures in conflict, these graphic compositions were in the vanguard of the battle paintings which, in the years to come, brought an increasing dynamism to depictions of combat.6 A small bronze statuette of the struggle between Hercules and Antaeus also attributed to Pollaiuolo

by Antonio Pollaiuolo himself give us a clue about the appearance of the full-sized paintings. Despite their small scale, the panels are unambiguous in their display of menace, power and masculine aggression. In these struggles to the death, monster and tyrant are overcome through the strength of the naked, muscular hero. Squeezing the last breath out of his opponent, Antaeus, the son of Poseidon and the earth goddess Gaia, Hercules lifts his adversary off the ground, the source of his foe's strength. While sculptural reliefs on antique sarcophagi may well have provided the artist with visual precedents for the locked-in movements of figures in conflict, these graphic compositions were in the vanguard of the battle paintings which, in the years to come, brought an increasing dynamism to depictions of combat.6 A small bronze statuette of the struggle between Hercules and Antaeus also attributed to Pollaiuolo similarly demonstrates a high level of artistic skill in being able to fix an intense moment of extreme exertion in a precious material and in the round.7

similarly demonstrates a high level of artistic skill in being able to fix an intense moment of extreme exertion in a precious material and in the round.7

In January 1504 Michelangelo's (1475–1564) giant free-standing marble statue of David was placed to the left of the entrance to the Palazzo della Signoria (now Palazzo Vecchio) .8 Probably around this date a second complementary sculpture was erected on the other side of the portal. By 1508 a large block of Carrara marble was being reserved for a statue in the piazza, again to be excuted by Michelangelo. However, the Republican government was again expelled from Florence in 1512. In 1515, the Medici Pope Leo X (1475–1521) made a triumphal entry into the city, confirming Medici control and the place of the Medici dynasty in Florentine history. In an ambitious attempt to gain the commission for the second marble sculpture in the Piazza della Signoria, the sculptor Baccio Bandinelli (1493–1560) produced a colossal stucco statue of Hercules for this event. At the time, Bandinelli supposedly boasted of his ability to surpass Michelangelo's David. By 1525 another Medici pope, Clement VII (1478–1534), was determined that Bandinelli should finish the statue instead of Michelangelo. This would neutralize the republican associations of a politically sensitive project that might be seen as a symbol of resistance to the Medici. When Alessandro Medici (1510–1537) became hereditary Duke of Florence, Bandinelli's statue of Hercules and Cacus

.8 Probably around this date a second complementary sculpture was erected on the other side of the portal. By 1508 a large block of Carrara marble was being reserved for a statue in the piazza, again to be excuted by Michelangelo. However, the Republican government was again expelled from Florence in 1512. In 1515, the Medici Pope Leo X (1475–1521) made a triumphal entry into the city, confirming Medici control and the place of the Medici dynasty in Florentine history. In an ambitious attempt to gain the commission for the second marble sculpture in the Piazza della Signoria, the sculptor Baccio Bandinelli (1493–1560) produced a colossal stucco statue of Hercules for this event. At the time, Bandinelli supposedly boasted of his ability to surpass Michelangelo's David. By 1525 another Medici pope, Clement VII (1478–1534), was determined that Bandinelli should finish the statue instead of Michelangelo. This would neutralize the republican associations of a politically sensitive project that might be seen as a symbol of resistance to the Medici. When Alessandro Medici (1510–1537) became hereditary Duke of Florence, Bandinelli's statue of Hercules and Cacus was unveiled in 1534 to widespread ridicule, with over one hundred scurrilous verses attached to its base.9 The two-figure group monumentalises the subjugation of Cacus by portraying the victor, having brought the monster to its knees, standing erect and locking it between his legs. There is, however, no psychological interaction between the two, nor is there anything of the dynamic physicality of the work of Antonio Pollaiuolo. This is certainly a symbol of powerful domination, but whether it is a model worthy of emulation is more doubtful, especially when compared to the frankness and youthful beauty of Michelangelo's David (or rather, since 1910, its replica) facing it.

was unveiled in 1534 to widespread ridicule, with over one hundred scurrilous verses attached to its base.9 The two-figure group monumentalises the subjugation of Cacus by portraying the victor, having brought the monster to its knees, standing erect and locking it between his legs. There is, however, no psychological interaction between the two, nor is there anything of the dynamic physicality of the work of Antonio Pollaiuolo. This is certainly a symbol of powerful domination, but whether it is a model worthy of emulation is more doubtful, especially when compared to the frankness and youthful beauty of Michelangelo's David (or rather, since 1910, its replica) facing it.

Medici rule had seriously compromised links that had been forged in Florence between the figure of Hercules triumphing over evil and a republican form of government. Such links were to re-emerge somewhat differently many years later in Europe at the time of the French Revolution. Before the late 18th century, the preference for Hercules as a model of virtue triumphing over vice was tied predominantly to more authoritarian forms of government in the lands of the Habsburgs, the Valois, the Bourbons and elsewhere. Subsequently, however, other, less violent and more contemplative aspects of the myth of Hercules came to the fore as a model to be emulated in the education of the princely ruler and of elite young men.

The Choice of Hercules

It was not only in close combat that Hercules could appear as a model of virtue. In Cesare Ripa's (1560–1645) Iconologia of 1593, the valour of Hercules is held to be both physical and intellectual.10 A youthful episode in the life of the hero which has received much attention fuses these two aspects of courage in a moment of decision.11 In Xenophon's (ca. 430 BC–354 BC) Memorabilia, Socrates (ca. 470 BC–399 BC) retells the speech of Prodicus (465 BC–395 BC), which relates how the young Hercules chose to follow the hard path of virtue rather than the easier, pleasurable path of vice, each personified by a female figure. The narrative was taken up by Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406) with the first complete Italian translation of the tale produced by Sassolo da Prato (ca. 1416–1449), a student at the school of Vittorino da Feltre (1378–1446) in Mantua. Its dedicatory epistle likens Alessandro Gonzaga (1427–1466) to Hercules and encourages him to follow the demigod's example in choosing virtue over vice.12 The tale again appeared in Antwerp in 1587, used by the antiquarian Stephanus Vinandus Pighius (1520–1604) as an allegory for the education of noble and princely young men, specifically his former pupil Karl-Friedrich (1555–1575), heir to the Duchy of Jülich Cleve-Berg.13

The key work in the fine arts for the wider transmission of this tale to connoisseurs, collectors and artists is Annibale Carracci's (1560–1609) painting of 1596. Here, Hercules – young, beardless, pensive, seemingly passive rather than physically active – is shown resting on his club beneath a palm tree, a symbol of the praise to come should he follow the path of virtue. Virtue’s female personification holds a sword and is clad modestly in a blue tunic with a red mantle as she points up to a barren, stony, hard and winding path which has the winged horse Pegasus at its summit, another bringer of fame. Below her sits a poet, crowned with laurels and holding open a book of heroic verse. Seen in rear view on the left, a diaphanously clad Vice gestures to a pleasant wooded area where a draped altar is set with the masks of deceit, with playing cards, musical instruments and sheet music.

The canvas was originally commissioned as the rectangular centrepiece of a decorative cycle for the Palazzo Farnese in Rome.14 The Camerino , on the first or principal floor of the palace, has its ceiling covered in frescos with the centre occupied by a copy of this painting, the original of which is now in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. Above and below the centrepiece are two further oval scenes that depict Hercules resting

, on the first or principal floor of the palace, has its ceiling covered in frescos with the centre occupied by a copy of this painting, the original of which is now in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. Above and below the centrepiece are two further oval scenes that depict Hercules resting and Hercules supporting the globe

and Hercules supporting the globe . Small grisaille roundels and medallions, painted to resemble moulded stucco plasterwork, show further labours of Hercules. The cycle honours its patron, Cardinal Odoardo Farnese (1573–1626). Its complex iconography is likely to have been devised by the scholar Fulvio Orsini (1529–1600), librarian to the Farnese for more than 30 years.15 Fusing the real with the imagined, the naked pagan demigod is here transformed, albeit somewhat anachronistically, into a force for high moral virtue in the context of the coming of age of the young cardinal and nobleman: like Hercules, it was in his power to acquire virtù by uniting knowledge with a capacity for action.

. Small grisaille roundels and medallions, painted to resemble moulded stucco plasterwork, show further labours of Hercules. The cycle honours its patron, Cardinal Odoardo Farnese (1573–1626). Its complex iconography is likely to have been devised by the scholar Fulvio Orsini (1529–1600), librarian to the Farnese for more than 30 years.15 Fusing the real with the imagined, the naked pagan demigod is here transformed, albeit somewhat anachronistically, into a force for high moral virtue in the context of the coming of age of the young cardinal and nobleman: like Hercules, it was in his power to acquire virtù by uniting knowledge with a capacity for action.

Frequently reproduced in painted copies, drawings and in prints, this visual composition of the choice of Hercules was recognized as a great masterpiece by Grand Tourists, elite young men and artists visiting Rome so as to learn from and admire the art and architecture of the Eternal City. One such tourist was Anthony Ashley Cooper, third Early of Shaftesbury (1671–1713), who visited the Palazzo Farnese in 1686. Three decades later he published, first in French and then in English, a treatise on the judgement of Hercules. Its aim was to encourage readers to emulate this virtuous example through the exercise of reason and of taste. Just as the young Hercules had chosen "a life full of Toil and Hardship under the Conduct of Virtue, for the deliverance of Mankind from Tyranny and Oppression", so should other men, including the creative artist.16 To illustrate his treatise the writer commissioned Paolo de Matteis (1662–1728) to produce a Choice of Hercules specifying in some detail what the picture should look like. The painting was also reproduced as an engraving

specifying in some detail what the picture should look like. The painting was also reproduced as an engraving to accompany the posthumous 1714 edition of Shaftesbury's Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times. Addressing the pose of Hercules, the moralist is concerned with how to depict the difficulty of the hero's choice through his body language

to accompany the posthumous 1714 edition of Shaftesbury's Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times. Addressing the pose of Hercules, the moralist is concerned with how to depict the difficulty of the hero's choice through his body language

…in the manner of his turn towards the worthier of these goddesses, he should by no means appear so averse or separate from the other, as not to suffer it to be conceived of him, that he had ever any inclination for her, or had ever hearkened to her voice. On the contrary, there ought to be some hopes, yet remaining for this latter goddess Pleasure, and some regret apparent in Hercules.17

The solution to this nuanced hesitancy is expressed in the composition, with the young hero standing in a slightly twisted pose (contrapposto), leaning on his club but at the same time looking to his right towards Virtue. This standing Hercules was modelled on the famous classical statue known as the Farnese Hercules , which was displayed between approximately 1556 and 1787 in the courtyard where Shaftesbury must have seen it on his visit to Rome.18

, which was displayed between approximately 1556 and 1787 in the courtyard where Shaftesbury must have seen it on his visit to Rome.18

The importance of this statue to the dissemination of knowledge in early modern Europe about antiquity, classical sculpture and artistic practice cannot be overstated. It is significant that this figure is not in active, fighting mode but in a static, contemplative pose, as if Hercules was resting after his labours. We have some indication of the ways in which the sculpture was appreciated during the 18th century by a view of the Farnese courtyard that the French artist Louis Chays (ca. 1740–1810) captured in a presentation drawing . Fashionably clothed visitors are shown admiring the colossal sculpture from the rear, while artists draw from some of the choicest examples of antique sculpture in the Farnese collection – including, of course, the Hercules itself. Chays's drawing represents the communities of visitors to Rome, although the classical dress and semi-nudity of some of the onlookers are in homage to antiquity and suggest that this scene ought not to be taken as a literal record.

. Fashionably clothed visitors are shown admiring the colossal sculpture from the rear, while artists draw from some of the choicest examples of antique sculpture in the Farnese collection – including, of course, the Hercules itself. Chays's drawing represents the communities of visitors to Rome, although the classical dress and semi-nudity of some of the onlookers are in homage to antiquity and suggest that this scene ought not to be taken as a literal record.

The Practice and Theory of Art

Drawing from classical specimens – either from the original sculpture or from copies in bronze, marble, plaster or in the form of prints – became, in the second half of the 16th century, an established part of artistic training, fostered throughout Europe by academies of art.19 The Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture in Paris had a particularly extensive training programme and in 1668 established a branch in Rome, the Académie de France à Rome, where prize-winning students from Paris were sent for several years to finish off their training by studying antiquity in situ. In so doing they were also to supply Paris with copies of major classical and Renaissance works of art. In conjunction with this practical training, a body of art theory developed back in Paris through lectures, debates, discussions and publications in which individual works of art were closely examined for their principles of composition, invention, expression, proportion, perspective and anatomy. One such discussion was prompted by the sculptor Michel Anguier (1612–1686) who, after having spent time in Rome and having made a bronze two-figure group of Hercules and Atlas , delivered a lecture on the proportions of the Farnese Hercules in Paris on 9 December 1669.20 The lecture was repeated several times. In some lecture summaries of 1680, published by the secretary to the Académie royale, Henri Testelin (1616–1695), there is an accompanying print outlining examples of the proportions and contours of a variety of classical sculptures. The print has at its centre the colossal figure of the Farnese Hercules flanked by a second classical Herculean sculpture, the figure of Commodus as Hercules

, delivered a lecture on the proportions of the Farnese Hercules in Paris on 9 December 1669.20 The lecture was repeated several times. In some lecture summaries of 1680, published by the secretary to the Académie royale, Henri Testelin (1616–1695), there is an accompanying print outlining examples of the proportions and contours of a variety of classical sculptures. The print has at its centre the colossal figure of the Farnese Hercules flanked by a second classical Herculean sculpture, the figure of Commodus as Hercules .

.

Earlier, the Flemish artist, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) had also studied in Rome before basing himself in Antwerp, where he obtained commissions from all the major European courts. Even though he left no published treatise on the theory of art, he was deeply imbued with classical learning, scholarship and the cultures of antiquity, noting down aspects relevant to his own practice in a pocketbook. Much of this pocketbook was burnt in 1720, but a short Latin tract based on the surviving portions, De imitatione statuarum, was published posthumously in 1708 alongside a French translation by the then owner of the pocketbook, Roger de Piles (1635–1709).21 The text recommends that the painter take a cautionary approach when imitating antique sculpture. Beginners were not to learn from marbles that were crude, stiff and with harsh anatomies; rather, care was to be taken in selecting appropriate models, for the painter had to understand antiquity in order to apply its precepts to the different medium of painting. The ability to render the motions of the body, the skin's flexibility and the play of light on flesh in paint required a thorough knowledge of classical sculpture. This knowledge was to arise not from a slavish copying but from the creative adaptation and reuse of known and approved sculptural prototypes. Under the bilingual heading Vir HPAKɅEƩ, an extant fragment from the pocketbook is inscribed on its verso with notes in Latin and a cubic analysis of the Farnese Hercules. On the recto of the sheet there are back and side views that similarly reduce this figure to the elemental forms of square, arc and equilateral triangle .

.

The notes by Rubens are in part concerned with the perceived degeneracy, decay, corruption and weakness of the artist's own times, which are unfavourably compared to a lost golden age of antiquity peopled with heroes, giants and cyclopes. The ancients had exercised their bodies every day, sometimes even to an excess of sweat and fatigue. This discipline contrasted with the pot bellies and weak limbs evident in the artist's own times, which resulted from gluttony, idleness, and lack of exercise. Such jottings engaged with ongoing debates in which the greatness of the ancients was pitted against the achievements of the moderns. Initially a literary dispute arising out of the renewal of interest in antiquity, the "Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns" spread over into the arts and sciences, into politics and religion. One side argued that ancient culture was superior while the other side challenged this view by pointing to progress in technology, scientific enquiry and intellectual endeavour.22

Pendant capriccio paintings [

[ ] by Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691–1765) elegantly interpret this battle or quarrel in views that depict the treasures first of ancient and then of modern Rome. Commissioned by the French ambassador to Rome, the Duc de Choiseul (1719–1785), the works enact a dialogue between the ancient and the modern. The educated and noble collector would have recognized it as an assemblage that was not topographically true. However, the separate parts of the composition offered the viewer the delightful opportunity to spot the best of what both modern and ancient Rome still had to offer.23 Architecture and statuary have here been set within the conceits of framed pictures and fantasy galleries. Prominent in the imaginary modern view are St Peter's and Michelangelo's Moses, whilst the view of Ancient Rome with the imposing monuments of the Pantheon and the Colosseum features the Farnese Hercules on the left and Laocoön on the right. These are perhaps the two best-known and most frequently reproduced classical sculptures in the city.

] by Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691–1765) elegantly interpret this battle or quarrel in views that depict the treasures first of ancient and then of modern Rome. Commissioned by the French ambassador to Rome, the Duc de Choiseul (1719–1785), the works enact a dialogue between the ancient and the modern. The educated and noble collector would have recognized it as an assemblage that was not topographically true. However, the separate parts of the composition offered the viewer the delightful opportunity to spot the best of what both modern and ancient Rome still had to offer.23 Architecture and statuary have here been set within the conceits of framed pictures and fantasy galleries. Prominent in the imaginary modern view are St Peter's and Michelangelo's Moses, whilst the view of Ancient Rome with the imposing monuments of the Pantheon and the Colosseum features the Farnese Hercules on the left and Laocoön on the right. These are perhaps the two best-known and most frequently reproduced classical sculptures in the city.

The figurative forms of antique sculpture representing the hero Hercules were used in the training of artists as approved classical models in early modern Europe. As well as serving as a model for the artist, the motif of Hercules overcoming vice attained wide currency in cultivating the image of the princely ruler.

The Princely Ruler

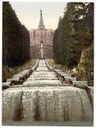

As well as playing a distinct role in the education of young men, in the training of artists, and in circles of connoisseurs and collectors, the figure of Hercules served as a model to the princely ruler who aimed to project the image of his power, courage, virtue and active fortitude by likening himself to a virtuous, courageous, heroic demigod predecessor. The Hercules monument in Kassel, erected between 1707 and 1717, for instance, is the most monumental recreation of the Farnese Hercules, now widely recognised as a model piece of classical sculpture. Cast in copper and over eight metres high, this gigantic statue stands today on a colossal octagon topped by a pyramid at the highest and focal point of the Schloss Wilhelmshöhe Bergpark . The monument was designed by Giovanni Francesco Guerniero (1665–1745) and commissioned by Landgrave Karl von Hessen-Kassel (1654–1730), who was keen to re-establish the power and and prosperity of his domain after the devastations of the Thirty Years' War.24

. The monument was designed by Giovanni Francesco Guerniero (1665–1745) and commissioned by Landgrave Karl von Hessen-Kassel (1654–1730), who was keen to re-establish the power and and prosperity of his domain after the devastations of the Thirty Years' War.24

Another manifestation of Hercules in the service of princely power is the painting The Apotheosis of Hercules by François Lemoyne (1688–1737) in the Salon d'Hercule at Versailles. The painting, unveiled on 26 September 1736 by Louis XV (1710–1774), spans 480 metres and shows a celestial gathering of the Olympian gods.25 One scene depicts Jupiter, the most powerful Roman deity, seated on a throne while offering the hand of Hebe to Hercules, who is standing in his chariot. Mostly joyful and pacifist in tone and with heroic virtue being suitably rewarded, albeit in the heavens above the heads of courtiers, this gathering is more about love, creativity and fertility than about combat, conflict and the arts of war.

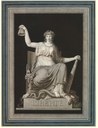

Many dynasties, including those of the Gallic Empire, Burgundy and Navarre even claimed descent from Hercules, whilst extensive use of the figure of Hercules was made by the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs, the Valois as well as the Bourbon Kings of France, and the house of Lorraine.26 Two notable examples in print form refer to the royal house of Braganza in Portugal, specifically to King José I (1714–1777). One print , executed by Eleutério Manuel de Barros (1754–1812) after a design by Joaquim Carneiro da Silva (1727–1818) celebrates the inauguration of the equestrian statue of King José I in the new main square in Lisbon in an area that had been devastated by the earthquake of 1755.27 The allegory has a winged angel of immortality with a serpent eating its tail, a symbol of eternal cyclical renewal, crowning a naked Hercules with his usual attributes of lion, lionskin and club. Trampling on snakes, the heroic pagan hero raises up a female personification of Lisbon emerging from ruins and holding a model of the equestrian statue. The second print

, executed by Eleutério Manuel de Barros (1754–1812) after a design by Joaquim Carneiro da Silva (1727–1818) celebrates the inauguration of the equestrian statue of King José I in the new main square in Lisbon in an area that had been devastated by the earthquake of 1755.27 The allegory has a winged angel of immortality with a serpent eating its tail, a symbol of eternal cyclical renewal, crowning a naked Hercules with his usual attributes of lion, lionskin and club. Trampling on snakes, the heroic pagan hero raises up a female personification of Lisbon emerging from ruins and holding a model of the equestrian statue. The second print depicts the heroic figure of José I himself in the guise of Hercules, tamer of monsters, as he crushes the multiple heads of the hydra, each of them wearing a Jesuit cap. Here the female personification of Portugal kisses the hero's hand in gratitude for having expelled the Jesuits from the lands of Portugal.

depicts the heroic figure of José I himself in the guise of Hercules, tamer of monsters, as he crushes the multiple heads of the hydra, each of them wearing a Jesuit cap. Here the female personification of Portugal kisses the hero's hand in gratitude for having expelled the Jesuits from the lands of Portugal.

In the course of the French Revolution, the authority of the princely model collapsed and with it the plausibility of likening a nation's ruler to Hercules. Yet some of the features associated with the fighting warrior hero of antiquity were transferred to the personification of the French people at its most militant. One attribute, the gnarled, tapering club, was often shown with the hydra beneath it to symbolise the defeat of despotism, as in an allegory of Liberty designed by Jean-Guillaume Moitte (1746–1810).28 This is not a complete reversion to the use of Hercules exemplified by the Florentine Republic, where the figure was seen as a sign of civic virtue rather than royal or aristocratic endeavour. The legacies of the intervening period meant that the power of the French kings could not be so easily inverted. Hercules also had a familiar backstory, unlike the female figure of liberty. She enters the scene as an empty communicative vessel that can be turned more easily towards universalising, abstract principles. By endowing this abstract personification with a familiar attribute of Hercules, the weapon representing his strength, the female personification acquires additional layers of meaning without compromising its edifying character, rhetorical force and novelty.29 However, as the Revolution unfolded, not all references to Hercules remained quite so oblique. In 1795, after the "Thermidorian Reaction" and the downfall of the radical Jacobin leader Maximilien Robespierre (1758–1794), the republic's new silver coinage

designed by Jean-Guillaume Moitte (1746–1810).28 This is not a complete reversion to the use of Hercules exemplified by the Florentine Republic, where the figure was seen as a sign of civic virtue rather than royal or aristocratic endeavour. The legacies of the intervening period meant that the power of the French kings could not be so easily inverted. Hercules also had a familiar backstory, unlike the female figure of liberty. She enters the scene as an empty communicative vessel that can be turned more easily towards universalising, abstract principles. By endowing this abstract personification with a familiar attribute of Hercules, the weapon representing his strength, the female personification acquires additional layers of meaning without compromising its edifying character, rhetorical force and novelty.29 However, as the Revolution unfolded, not all references to Hercules remained quite so oblique. In 1795, after the "Thermidorian Reaction" and the downfall of the radical Jacobin leader Maximilien Robespierre (1758–1794), the republic's new silver coinage designed by Augustin Dupré (1748–1833), depicted Hercules embracing the female personifications of liberty and equality. The semi-divine Hercules, who could be valued as a model of virtue and, allegorically, a strong marker of unity, now offered symbolic identification to the French people as a whole.

designed by Augustin Dupré (1748–1833), depicted Hercules embracing the female personifications of liberty and equality. The semi-divine Hercules, who could be valued as a model of virtue and, allegorically, a strong marker of unity, now offered symbolic identification to the French people as a whole.

The Model Undone

Less positive, more damaging inflections have, however, also accrued to the figure of Hercules. Portrayed sometimes as a comic, sometimes as a tragic figure in literature, drama, opera, dance and on film, depictions of his huge, naked torso bulging with strained muscles raise issues about his masculinity, or rather hyper-masculinity, which then lead to his becoming the butt of censure and/or ridicule.30 The engraving of The Great Hercules, also known as Knollenman or bulbous man , by Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) appears, at first sight, to be just such a rather too monstrous embodiment. The foreground of this composition has a colossal Hercules confronting the viewer with a boldly naked body of bulging muscles, long hair and bushy moustache – but with quite a disproportionately small penis. In one large hand Hercules holds a horn, torn from the shape-shifting river-god Achelous (shown behind in the form of a bull being defeated), and in the other a massive club. Does this depiction communicate something about the dangers of excess in aggressively masculine and militant behaviour? In 1682, almost a hundred years after the first appearance of the print, the Dutch art theorist Willem Goeree (1635–1711) noted that this figure had been called "den Appel-sak van Goltzius".31 The word zak is Dutch slang for scrotum, so this is unlikely to be a direct reference to the three golden apples of the Hesperides retrieved by Hercules after slaying the serpent Ladon. Aside from being a figure of fun, it has also been suggested that this print, first published in Haarlem in 1589 during a violent civil war, might well echo the instability of the body politic. During this period, known as "The Troubles", the Netherlands were torn between Spanish Habsburg rule and the breakaway Dutch Republic, which promised freedom and power but had not yet been able to establish stability on the territories it claimed to rule.32

, by Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) appears, at first sight, to be just such a rather too monstrous embodiment. The foreground of this composition has a colossal Hercules confronting the viewer with a boldly naked body of bulging muscles, long hair and bushy moustache – but with quite a disproportionately small penis. In one large hand Hercules holds a horn, torn from the shape-shifting river-god Achelous (shown behind in the form of a bull being defeated), and in the other a massive club. Does this depiction communicate something about the dangers of excess in aggressively masculine and militant behaviour? In 1682, almost a hundred years after the first appearance of the print, the Dutch art theorist Willem Goeree (1635–1711) noted that this figure had been called "den Appel-sak van Goltzius".31 The word zak is Dutch slang for scrotum, so this is unlikely to be a direct reference to the three golden apples of the Hesperides retrieved by Hercules after slaying the serpent Ladon. Aside from being a figure of fun, it has also been suggested that this print, first published in Haarlem in 1589 during a violent civil war, might well echo the instability of the body politic. During this period, known as "The Troubles", the Netherlands were torn between Spanish Habsburg rule and the breakaway Dutch Republic, which promised freedom and power but had not yet been able to establish stability on the territories it claimed to rule.32

Rubens certainly upheld Hercules as a colossal figure from antiquity even when he depicted the virile hero as a figure of fun, enslaved to the Lydian queen Omphale. The painting was created around 1606 when Rubens was in Italy as court artist to the Duke of Mantua, Vincenzo Gonzaga (1562–1612), and may have been commissioned by the Genoese Gian Vincenzo Imperiale (1582–1640) on the occasion of his wedding.33 It depicts the subject of Hercules mocked by Omphale . Surviving Greek and Latin sources for the narrative make much of the inversion implied by servitude to a woman which the hero underwent in order to expiate his murder, in a fit of madness, of Iphitos.34 The interpretation of the story by Rubens makes the unmanning blatantly explicit. Shown with purloined club and lionskin, Omphale tweaks the ear of Hercules who, almost naked, occupies the centre of the image. With only a coloured piece of silk-like cloth covering his hair and genitals, he holds a fine thread and distaff, symbols of feminine labour. He appears also to be romantically smitten, thus making him powerless to fight back in spite of his muscular physique and fiery temperament. Two young courtiers with yarn and other spinning implements sit at his knee whilst behind, unseen by the hero, stands an old woman making the cuckold sign with her fingers. It is possible to infer that the strongman has been brought down partly on account of his love for a woman, something perhaps in the manner of the biblical Samson. The culture of early modern Europe was also familiar with the tradition of the "world upside down", in which the woman is equipped with the weapons of warfare whilst the man takes on the domestic tasks normally considered beneath his dignity.35 Often moralizing in intent and supporting the reassertion of order, the comic and entertaining potential of the particular episode of Hercules and Omphale had already been brought out by Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586) in 1595:

. Surviving Greek and Latin sources for the narrative make much of the inversion implied by servitude to a woman which the hero underwent in order to expiate his murder, in a fit of madness, of Iphitos.34 The interpretation of the story by Rubens makes the unmanning blatantly explicit. Shown with purloined club and lionskin, Omphale tweaks the ear of Hercules who, almost naked, occupies the centre of the image. With only a coloured piece of silk-like cloth covering his hair and genitals, he holds a fine thread and distaff, symbols of feminine labour. He appears also to be romantically smitten, thus making him powerless to fight back in spite of his muscular physique and fiery temperament. Two young courtiers with yarn and other spinning implements sit at his knee whilst behind, unseen by the hero, stands an old woman making the cuckold sign with her fingers. It is possible to infer that the strongman has been brought down partly on account of his love for a woman, something perhaps in the manner of the biblical Samson. The culture of early modern Europe was also familiar with the tradition of the "world upside down", in which the woman is equipped with the weapons of warfare whilst the man takes on the domestic tasks normally considered beneath his dignity.35 Often moralizing in intent and supporting the reassertion of order, the comic and entertaining potential of the particular episode of Hercules and Omphale had already been brought out by Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586) in 1595:

So in Hercules painted with his great beard and furious countenaunce, in a women's attyre, spinning at Omphale's commaundement, it breedeth both delight and laughter: for the representing of so straunge a power of Love, procures delight, and the scornefulnesse of the actions stirrith laughter.36

Fits of uncontrolled passion leading to excessive violence and ultimately murder belong to the downsides of the deeds for which Hercules is known. Such episodes are much rarer in the visual iconography of the hero than those of the fighting Hercules. However, a painting by Christoph Unterberger (1732–1798) on a ceiling of the Villa Borghese in Rome and a monumental sculpture by Antonio Canova (1757–1822)[

and a monumental sculpture by Antonio Canova (1757–1822)[ ] show how the hero's misdirected strength can be turned into something visually frightening. Both works depict the murder of the servant Lichas by Hercules, tormented by the pain of the poisoned blood-soaked garment inadvertently sent by his wife Deianeira and handed to him by Lichas. Grabbing hold of the servant, he whirls him in the air and hurls him into the sea.37 In Ovid's Metamorphosis, Lichas is turned to stone as he hurtles through the air, and something of this powerful transformation is captured in Canova's colossal statue. The two-figure group, which is over three metres high, has the hapless servant, upside down, grasped both by the hair and the foot. He is howling with fear and trying to save himself by holding on to the lion's mane. The limbs of Hercules are stretched to extreme limits. This is a display of physical exertion, brutal force and uncontrolled passion, raging, excessive and aberrant. The sculpture had originally been commissioned by the collector Don Onorato Gaetani dell'Aquila d'Aragona (1770–1857), a minister of the Bourbon king of Naples. However, it was abandoned in 1798 when the French occupied Naples and Gaetani had to go into exile. Given the changing political situation, past associations between Hercules and Bourbon monarchic rule, whether for good or bad, had become impossible to sustain. Completed in 1815, the work had by then been purchased by Prince Raimondi Torlonia (1755–1829) for his new palace in the Piazza Venezia, Rome.

] show how the hero's misdirected strength can be turned into something visually frightening. Both works depict the murder of the servant Lichas by Hercules, tormented by the pain of the poisoned blood-soaked garment inadvertently sent by his wife Deianeira and handed to him by Lichas. Grabbing hold of the servant, he whirls him in the air and hurls him into the sea.37 In Ovid's Metamorphosis, Lichas is turned to stone as he hurtles through the air, and something of this powerful transformation is captured in Canova's colossal statue. The two-figure group, which is over three metres high, has the hapless servant, upside down, grasped both by the hair and the foot. He is howling with fear and trying to save himself by holding on to the lion's mane. The limbs of Hercules are stretched to extreme limits. This is a display of physical exertion, brutal force and uncontrolled passion, raging, excessive and aberrant. The sculpture had originally been commissioned by the collector Don Onorato Gaetani dell'Aquila d'Aragona (1770–1857), a minister of the Bourbon king of Naples. However, it was abandoned in 1798 when the French occupied Naples and Gaetani had to go into exile. Given the changing political situation, past associations between Hercules and Bourbon monarchic rule, whether for good or bad, had become impossible to sustain. Completed in 1815, the work had by then been purchased by Prince Raimondi Torlonia (1755–1829) for his new palace in the Piazza Venezia, Rome.

At the start of the 19th century, the scholarship of the German antiquarian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) encouraged the emergence of Greek art from the shadows of Rome and prompted a wider culture of Greek revival. The naked body of the heroic young male came to be imbued with notions of beauty, aesthetic value, interiority and poetic imagination quite at odds with the muscular vigour of the fighting Hercules.38 Winckelmann had, however, admired Hercules in a "Beschreibung des Torso im Belvedere zu Rom", believing that this torso depicted the hero resting and deified after his labour.39 In this text the writer, travelling through the imagined world of Hercules and reliving his past, imagines the mutilated stone as whole. Eventually, however, there is a recognition that the torso is, in fact, a relic, albeit one of great beauty.40 This subjective encounter with a sensuously charged work was to inflect approaches to Hercules in Germany and elsewhere in the decades to come. In the large canvas of Hercules wrestling with death for the body of Alcestis by Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830–1896), we see Hercules in rear view, straining every sinew in his fight with Thanatos, messenger of death. However, the centre of the composition is occupied by the inert, cold, lifeless body of Alcestis. The narrative of a significant moment has given way here to mood, emotion and beauty – specifically, to female beauty threatened.41

depicted the hero resting and deified after his labour.39 In this text the writer, travelling through the imagined world of Hercules and reliving his past, imagines the mutilated stone as whole. Eventually, however, there is a recognition that the torso is, in fact, a relic, albeit one of great beauty.40 This subjective encounter with a sensuously charged work was to inflect approaches to Hercules in Germany and elsewhere in the decades to come. In the large canvas of Hercules wrestling with death for the body of Alcestis by Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830–1896), we see Hercules in rear view, straining every sinew in his fight with Thanatos, messenger of death. However, the centre of the composition is occupied by the inert, cold, lifeless body of Alcestis. The narrative of a significant moment has given way here to mood, emotion and beauty – specifically, to female beauty threatened.41

In the early modern period, the figure of the semi-divine pagan hero Hercules frequently acquired political connotations. He was often looked up to as a model of virtuous conduct, whether of republican government or of princely rule. These connotations existed alongside evolving aesthetic considerations, with the Farnese Hercules in particular standing at the forefront of a "canon" of universally admired classical sculpture. Besides featuring in the education of young noblemen, this model was widely held up for emulation and adaptation in the training of artists. Within the oligarchic autocracies of the day, however, the exemplariness of Hercules had a darker side. The hyper-masculine monster-slaying superhero might be undone by the excessive and injudicious use of his own power, just as the power of the absolute ruler came increasingly to be regarded as morally questionable and politically problematic.

Valerie Mainz

Appendix

Sources

Anguier, Michel: L'Hercule Farnèse, in: Jacqueline Lichtenstein et al. (eds.): Conférences de l'Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, Paris 2006, vol. 1: Les Conférences au temps d'Henry Testelin 1648–1681, pp. 323–339. URL: https://perspectivia.net/publikationen/conference/conferences_tome1/conferences_tome1_vol1 [2024-07-05]

Beaune, Henri et al. (eds.): Mémoires d'Olivier de la Marche, Paris 1883. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6549624s [2024-07-05]

Goeree, Willem: Natuurlyk en schilderkonstig ontwerp der menschkunde, Amsterdam 1682. URN: urn:oclc:record:299831412 [2024-07-05]

Piles, Roger de: Cours de Peinture par Principes, Paris 1708. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1051278h [2024-07-05]

Salutati, Coluccio: De laboribus Herculis, ed. by Berthold Ullman, Zürich 1951.

Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper of: A Notion of the Historical Draught or Tablature of the Judgement of Hercules according to Prodicus, lib.II. Xen. de mem. Soc., London 1713.

Testelin, Henri: Sentimens des plus habiles peintres sur la pratique de la peinture et sculpture, mis en Tables de préceptes avec plusieurs discours académiques, Paris 1696. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1516423w [2024-07-05]

Vasari, Giorgio: Le Vite de' piú eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri, Torino 1986.

Winckelmann, Johann Joachim: Beschreibung des Torso im Belvedere zu Rom, in: Johann Joachim Winckelmann: Kleine Schriften: Vorreden, Entwürfe, ed. by Walther Rehm, Berlin 1968.

Literature

Allan, Arlene et al. (eds.): Herakles Inside and Outside the Church, Leiden et al. 2020 (Metaforms 18). URL: https://brill.com/display/title/56765 [2024-07-05]

Aymonino, Adriano / Varick Lauder, Anne: Drawn from the Antique: Artists & the Classical Ideal, London 2015.

Baecque, Antoine de: Les Dames de la République: Images allégoriques féminines pendant la Révolution, in: Marie-France Brive (ed.): Les Femmes et la Révolution française, Toulouse 1990, pp. 189–193.

Braider, Christopher, Baroque self-invention and historical truth: Hercules at the crossroads, Aldershot 2004.

Bullard, Paddy et al. (eds.): Ancients and Moderns in Europe: Comparative Perspectives, Oxford 2016 (Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment 2016, 6). URL: https://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/doi/book/10.3828/9780729411776 [2024-07-05]

Bush, Virginia: Bandinelli's "Hercules and Cacus" and Florentine Traditions, in: Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 35 (1980), pp. 163–206. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/4238682 [2024-07-05]

Caballero González, Manuel: New Representations of Hercules' Madness in Modernity: The Depiction of Hercules and Lichas, in: Valerie Mainz et al. (eds): The Exemplary Hercules from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment and Beyond, Leiden et al. 2020, pp. 320–https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004435414_014 [2024-07-05]

Deligiannis, Ioannis: The Choice-Making Hercules as an Exemplary Model for Alessandro and Federico Gonzaga and the Fifteenth-Century Latin Translation of Prodikos' Tale of Herakles by Sassolo da Prato, in: Valerie Mainz et al. (eds): The Exemplary Hercules from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment and Beyond, Leiden et al. 2020, pp. 25–46. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004435414_003 [2024-07-05]

Desmond, Will D.: Hercules among the Germans: From Winckelmann to Hölderlin, in: Alastair Blanchard et al. (eds): The Modern Hercules: Images of the Hero from the Nineteenth to the Early Twenty-First Century, Leiden et al. 2020 (Metaforms 21), pp. 23–41. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004440067_003 [2024-07-05]

Ducamp, Emmanuel (ed): The Apotheosis of Hercules by François Lemoyne at the château de Versailles: history and restoration of a masterpiece, Paris, 2002.

Ettlinger, Leopold D.: Hercules Florentinus, in: Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 16,2 (1972), pp. 119–42). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27652292 [2024-07-05]

Galinsky, Karl: The Herakles Theme: The Adaptations of the Hero in Literature from Homer to the Twentieth Century, Oxford 1972.

Haskell, Francis / Penny, Nicholas: Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500–1900, New Haven et al. 1981.

Hessert, Marlis v.: Zum Bedeutungswandel der Herkules-Figur in Florenz: Von den Anfängen der Republik bis zum Prinzipat Cosimos I, Cologne et al. 1991.

Hunt, Lynn: Hercules and the radical image in the French Revolution, in: Representations 2 (1983), pp. 95–117. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/2928385 [2024-07-05]

Jaffé, Michael: Van Dyck's Antwerp Sketchbook, London 1966, vol. 1–2.

Jones, Stephen: Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis, in: Stephen Jones et al. (eds): Frederic, Lord Leighton: Eminent Victorian Artist, London 1996, pp. 168–169.

Kray, Ralph / Oettermann, Stephan: Herakles, Herkules Basel et al. 1994, vol. 1: Metamorphosen des Heros in ihrer medialen Vielfalt,.

Kray, Ralph / Oettermann, Stephan: Herakles, Herkules, Basel et al. 1994, vol. 2: Medienhistorischer Aufriss: Repertorium zur intermedialen Stoff- und Motivgeschichte.

Laruelle, Anne-Sophie: Hercules in the Art of Flemish Tapestry (1450–1565), in: Valerie Mainz et al. (eds): The Exemplary Hercules from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment and Beyond, Leiden et al. 2020 (Metaforms 20), pp. 97–118. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004435414_005 [2024-07-05]

Macsotay, Tomas: How Hercules Lost His Poise: Reason, Youth and Fellowship in the Heroic Neoclassical Body, in: Valerie Mainz et al. (eds): The Exemplary Hercules from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment and Beyond, Leiden et al. 2020 (Metaforms 20), pp. 346–377. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004435414_015 [2024-07-05]

Mainz, Valerie: Hercules, His Club and the French Revolution, in: Valerie Mainz et al. (eds): The Exemplary Hercules from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment and Beyond, Leiden et al. 2020 (Metaforms 20), pp. 293–319. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004435414_013 [2024-07-05]

Martin, John Rupert: The Farnese Gallery, Princeton, 1965. URL: https://archive.org/details/farnesegallery0000mart [2024-07-05]

Medeiros Araújo, Filipa: "Monstrorum domitori": Emblematic and Allegorical Representations of the Herculean Tasks Performed by José I, King of Portugal (1714–77), in: Valerie Mainz et al. (eds): The Exemplary Hercules from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment and Beyond, Leiden et al. 2020 (Metaforms 20), pp. 149–171. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004435414_007 [2024-07-05]

Panofsky, Erwin: Hercules am Scheidewege und andere antike Bildstoffe in der neuern Kunst, Leipzig et al. 1930 (Studien der Bibliothek Warburg 18). URL: https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.29796 [2024-07-05]

Potts, Alex: Flesh and the Ideal: Winckelmann and the Origins of Art History, New Haven et al. 1994.

Rosenthal, Lisa: Gender, Politics and Allegory in the Art of Rubens, Cambridge 2005.

Sidney, Philipp: The Complete Works of Philip Sidney, ed. by Albert Feuillerat, Cambridge 1912, vol. 3. URL: https://www.proquest.com/publication/2059566?accountid=14632 [2024-07-05]

Simons, Patricia: Hercules in Italian Renaissance Art: Masculine Labour and Homoerotic Libido, in:. Art History 31,5 (2008), pp. 632–664. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.2008.00635.x [2024-07-05]

Stafford, Emma: Herakles: Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World, London 2012. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203152454 [2024-07-05]

Steil, Lucien (ed.): The Architectural Capriccio: Memory, Fantasy and Invention, London 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315241326 [2024-07-05]

Waldman, Louis: "Miracol' Novo et Raro": Two unpublished contemporary satires on Bandinelli's 'Hercules', in: Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 38,2/3 (1994), pp. 419–427. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27654386 [2024-07-05]

Woodall, Joanna: Monstrous Masculinity? Hendrick Goltzius' Engraving of "The Great Hercules", in: Valerie Mainz et al. (eds): The Exemplary Hercules from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment and Beyond, Leiden et al. 2020 (Metaforms 20), pp.194–234. URL: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004435414_009 [2024-07-05]

Wright, Alison: The Pollaiuolo Brothers: The Arts of Florence and Rome, New Haven et al. 2005.

Zemon Davis, Natalie: Society and Culture in Early Modern France: Eight Essays by Natalie Zemon Davis, Stanford 1975. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503621183 [2024-07-05]

Notes

- ^ "Florence subdues depravity with a Herculean club". See Wright, The Pollaiuolo Brothers 2005, p. 82. In the period covered by this contribution, the Latin name Hercules rather than the Greek Herakles was in general use.

- ^ Salutati, De laboribus Herculis 1951.

- ^ For the early Christian Herakles, see Allan, Herakles Inside and Outside the Church 2020.

- ^ See further Wright, The Pollaiuolo Brothers 2005, pp. 75–87.

- ^ Vasari, Le Vite 1986, pp. 483–484.

- ^ Major early examples include The Battle of Cascino by Michelangelo (1475–1564) and The Battle of Anghiari by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519).

- ^ It is, however, unlikely that such small, tactile objects, familiar to a circle of knowledgeable, erudite collectors close to the Medici, had any major impact as an emblem of the virtue of the city state.

- ^ Bush, Bandinelli's "Hercules and Cacus" 1980. Much of what follows about the sculpture is taken from this article.

- ^ Waldman, Miracol' novo et raro 1994.

- ^ Galinsky, The Herakles Theme 1972, p. 198.

- ^ For further on the choice of Hercules, see Panofsky, Hercules am Scheidewege 1930; Stafford, Herakles 2012.

- ^ Deligiannis, The Choice-making Hercules 2020.

- ^ Woodall, Monstrous Masculinity 2020.

- ^ Martin, The Farnese Gallery 1965.

- ^ Martin, The Farnese Gallery 1965, pp. 39–48.

- ^ Shaftesbury, A Notion 1713, p. 7.

- ^ Shaftesbury, A Notion 1713, p. 14.

- ^ For further on the Farnese Hercules, see Haskell / Penny, Taste and the Antique 1981, pp. 229–232. The statue had been recovered in pieces from the Roman Baths of Caracalla in the 1540s.

- ^ Aymonino / Varick Lauder, Drawn from the Antique 2015.

- ^ Anguier, L'Hercule Farnèse 1669.

- ^ Piles, Cours de peinture 1708, pp. 139–148. For more on this pocketbook, see Jaffé, Van Dyck's Antwerp Sketchbook 1966, vol 1, pp. 16–18.

- ^ See further Bullard, Ancients and Moderns in Europe 2016.

- ^ For the capriccio, see Steil, The Architectural Capriccio 2016.

- ^ en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hercules_monument_(Kassel)

- ^ For further on this ceiling painting, see Ducamp, The Apotheosis of Hercules 2001.

- ^ Beaune, Mémoires d'Olivier de la Marche 1883, vol 1, p. 43 cited in Laruelle, Hercules in Flemish Tapestry 2020, p. 101.

- ^ For more on this urban scheme, the equestrian statue and the print, see Medeiros Araújo, Monstrorum domitori 2020.

- ^ See Mainz, Hercules 2020.

- ^ For further on this argument, see de Baecque, Les Dames de la République 1989.

- ^ See above with reference to the statue of Hercules and Cacus in Florence. For literature and drama, see Galinsky, The Herakles Theme 1972; Stafford, Herakles 2012.

- ^ "The Apple-sack of Goltzius", Goeree, Natuurlyck 1682, p. 406 cited in Woodall, Monstrous Masculinity 2020, p. 212.

- ^ The insightful study by Joanna Woodall concludes that the work invites a constant renegotiation of the golden mean between vice and virtue on the way of the path to immortal virtue, Woodall, Monstrous Masculinity 2020.

- ^ For the painting, see Rosenthal, Gender, Politics and Allegory 2005, pp. 115–145.

- ^ Stafford, Herakles 2012, pp. 131–134.

- ^ Davis, Society and Culture 1975.

- ^ Sidney, The Complete Works 1912, vol. 3, p. 40, cited in Rosenthal, Gender, Politics and Allegory 2005, p. 113. Pictures showing Hercules and Omphale by Lucas Cranach the Elder had been popular with the Saxon Electors in the 1530s; see, for instance, Hercules with Omphale, Gotha, Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein.

- ^ For the narrative, see Stafford, Herakles 2012, p. 81, p. 99. See also Caballero González, New Representations 2020; Macsotay, How Hercules Lost His Poise 2020.

- ^ I take this argument from Macsotay, How Hercules Lost His Poise 2020.

- ^ Winckelmann, Beschreibung des Torso 1968; Haskell / Penny, Taste and the Antique 1981, pp. 229–232.

- ^ Desmond, Hercules among the Germans 2020.

- ^ For this painting, see Jones, Hercules Wrestling with Death 1996.